Australian Country Newspapers and Development Journalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CFS July.Indd 1 4/12/07 4:42:19 PM Aluminium Replacement for Isuzu, Hino and Safety Panels Mitsubishi Canter Trucks

Volume 117 December 2007 Print Post Approved - 535347/00018 CFS July.indd 1 4/12/07 4:42:19 PM Aluminium Replacement For Isuzu, Hino and Safety Panels Mitsubishi Canter trucks Front door quarter panel Vent FSS 550 101 LEFT FSS 550 801 LEFT FSS 550 102 RIGHT FSS 550 802 RIGHT Fender Blister FSS 550 601 LEFT FSS 550 602 RIGHT Door Blister Indicator Blanking Panel Corner FSS 550 501 LEFT FSS 550 400 FSS 550 502 RIGHT Panel FSS 550 301 LEFT FSS 550 302 RIGHT Mud Guard FSS 550 901 LEFT FSS 550 902 RIGHT Mud Guard Extension FSS 550 901X LEFT FSS 550 902X RIGHT Step Panel FSS 550 401 LEFT FSS 550 402 RIGHT Rear Door Plate For Dual Cab Front Door Plate FSS 550 701/R LEFT - FSS 550 702/R RIGHT FSS 550 701 LEFT - FSS 550 702 RIGHT Why install aluminium replacement safety panels ? In extreme conditions such as attending bushfires, plastic panels are simply not adequate. Newlans Coachbuilders have addressed this problem by designing and manufacturing aluminium replacement panels that will not rust or warp and can often be repaired after accident damage unlike plastic panels making them a one time investment and a long term budget saver. Newlans panels are easy to install and available pre-painted in fleet colours. Already widely used around Australia and New Zealand by most rural fire service orginisations Newlans aluminium replacement safety panels are a potentially life saving appliance upgrade. Tel: (08) 9444 1777 Fax: (08) 9444 1866 [email protected] 47 Gordon Road (East) coachbuilders Osborne Park 6017 Western Australia www.newlanscoachbuilders.com.au CFS July.indd 2 4/12/07 4:42:22 PM [ CONTENTS ] WELCOMES – 4 With messages from the Chief Officer, Minister for Emergency Services, CFSVA President and Public Affairs. -

Exploring the Impact of (Im)Mobilities on Rural and Regional Communities Report

1 Rural and Regional Mobilities Final Report Introduction This Rural and Regional Mobilities Workshop: Exploring the Impact of (Im)Mobilities in Rural and Regional Communities was presented by the Hawke EU Centre for Mobilities, Migrations and Cultural Transformations on 26 September 2017 at the University of South Australia’s Mount Gambier Campus. The workshop was presented in association with La Trobe University’s Department of Social Inquiry and Centre for the Study of the Inland. Characterised as being fixed, stable and homogenous communities, rural and regional areas are often viewed as largely untouched by the mobility of cosmopolitan, globalising dynamics associated with fast-paced connected urban centres. These notions have been challenged in recent years in Australia and Europe with claims that rural and regional communities have also experienced significant changes with increasing forms of mobility across a number of areas involving rural-to-rural, rural-to-urban, urban- to-rural or international-to-rural migration. Indeed it has been argued that ‘mobility is central to the enactment of the rural… and the rural is at least as mobile as the urban’ (Bell and Osti 2010). The workshop was an opportunity for academics involved in research in regional and rural Australian communities as well as key regional leaders and stakeholders to learn from one another and engage with the challenges associated with changing regional and rural mobilities. A key aim of the workshop was to suggest recommendations that will enable regional and rural communities to effectively respond to these challenges. These challenges are not unique to the Australian context. We are also pleased that the Regional and Rural Mobilities Workshop was able to draw on the experiences and lessons learned from recent migration challenges in Europe (Germany) and New Zealand. -

Aap Submission to the Senate Inquiry on Media Diversity

AAP SUBMISSION TO THE SENATE INQUIRY ON MEDIA DIVERSITY AAP thanks the Senate for the opportunity to make a submission on the Inquiry into Media Diversity in Australia. What is a newswire A newswire is essentially a wholesaler of fact-based news content (text, pictures and video). It reports on politics, business, courts, sport and other news and provides this to other media outlets such as newspapers, radio and TV news. Often the newswire provides the only reporting on a subject and hence its decisions as to what to report play a very important role in informing Australians about matters of public interest. It is essential democratic infrastructure. A newswire often partners with other global newswire agencies to bring international stories to a domestic audience and also to take domestic stories out to a global audience. Newswires provided by news agencies have traditionally served as the backbone of the news supply of their respective countries. Due to their business model they contribute strongly to the diversity of media. In general there is a price for a defined number of circulation – be it printed papers, recipients of TV or radio broadcasters or digital recipients. The bigger the circulation, the higher the price thus making the same newswire accessible for small media with less purchasing power as well as for large media conglomerates with strong financial resources.1 This co-operative business model has been practically accepted world-wide since the founding of the Associated Press (AP) in the USA in the mid-19th century. Newswire agencies are “among the oldest media institutions to survive the evolution of media production from the age of the telegraph to the age of 2 platform technologies”. -

Environmental Impact Report Drilling, Completion and Well Production Testing in the Otway Basin, South Australia December 2018

Environmental Impact Report Drilling, Completion and Well Production Testing in the Otway Basin, South Australia December 2018 EIR Drilling, Completion & Well Production Testing in the Otway Basin SA | December 2018 Document Control Revision # Purpose Author Reviewer Approver Date 0 Issued for submission SM SM SM 4/10/2013 1 Finalised following agency consultation SM BW SM 12/11/2013 2 Final DMITRE comments addressed TF SM SM 13/11/2013 3 5-year review update - draft for internal review ZB/MM SM TF 26/11/2018 4 5-year review update - draft for consultation BW SM TF 30/11/2018 EIR Drilling, Completion & Well Production Testing in the Otway Basin SA | December 2018 Contents 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Background ............................................................................................................................. 4 1.2 Beach Energy Company Profile ............................................................................................... 4 1.3 About this document .............................................................................................................. 6 1.3.1 Scope ............................................................................................................................... 6 2 Legislative Framework .................................................................................................................... 8 2.1 Petroleum and Geothermal Energy -

Publications and Websites

Publications and Websites FAIRFAX MEDIA AUSTRALIAN PUBLICATIONS Harden Murrumburrah Express Metropolitan Newspapers Greater Dandenong Weekly Hawkesbury Courier Hobsons Bay Weekly Hawkesbury Gazette The Sydney Morning Herald Hobsons Bay Weekly - Williamstown Hibiscus Happynings The Sun-Herald Hume Weekly Highlands Post (Bowral) The Age Knox Weekly Hunter Valley News The Sunday Age Macedon Ranges Weekly Hunter Valley Town + Country Leader Lithgow Mercury Maribyrnong Weekly Lower Hunter Star (Maitland) Maroondah Weekly Canberra/Newcastle/Illawarra/ Macleay Argus Seniors Group Melbourne Times Weekly Mailbox Shopper Melbourne Weekly Manning Great Lakes Extra ACT Melbourne Weekly Bayside Manning River Times The Canberra Times Melbourne Weekly Eastern Merimbula News Weekly The Chronicle Melbourne Weekly Port Phillip Midcoast Happenings Public Sector Informant Melton Weekly Mid-Coast Observer Sunday Canberra Times Monash Weekly Midstate Observer The Queanbeyan Age Moonee Valley Weekly Milton Ulladulla Times Moorabool Weekly Moree Champion Illawarra Northern Weekly Moruya Examiner Illawarra Mercury North West Weekly Mudgee Guardian Wollongong Advertiser Pakenham Weekly Mudgee Weekly Muswellbrook Chronicle Newcastle Peninsula Weekly - Mornington Point Cook Weekly Myall Coast NOTA Coasting Narooma News Sunbury Weekly Lakes Mail Narromine News Port Stephens Examiner Western Port Trader North Coast Senior Lifestyle The Newcastle Herald Western Port Weekly North Coast Town + Country Magazine The Star (Newcastle and Lake Wyndham Weekly Northern Daily -

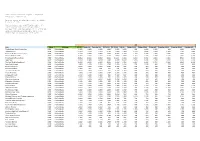

Emma™ Print Audience Report - Regional Newspapers (Modelled)

emma™ Print Audience Report - Regional Newspapers (Modelled) Average Issue Readership (AIR), rounded to nearest '00 AIR estimates are modelled based on the emma™ survey data collected between October 2013 and September 2017, and AMAA audited circulation figures from June 2017 (ABC) or September 2017 (CAB). AIR Title State Publisher All 14+ Males 14+ Females 14+ All 14-44 All 45-64 All 65+ Males 14-44 Males 45-64 Males 65+ Females 14-44 Females 45-64 Females 65+ The Bellingen Shire Courier-Sun NSW Fairfax Media 6,100 2,900 3,200 1,600 2,500 2,000 800 1,200 1,000 800 1,300 1,100 Highlands Post NSW Fairfax Media 11,600 5,300 6,300 2,700 3,900 5,100 1,200 1,800 2,300 1,400 2,100 2,800 Eurobodalla Shire Independent NSW Fairfax Media 13,200 5,800 7,400 3,300 4,600 5,300 1,300 2,000 2,600 2,000 2,600 2,700 Milton Ulladulla Times NSW Fairfax Media 10,400 5,000 5,400 2,700 3,800 3,900 1,200 1,900 1,900 1,500 1,900 2,000 Shoalhaven & Nowra News NSW Fairfax Media 26,800 13,200 13,600 8,200 10,200 8,400 3,800 4,700 4,800 4,400 5,500 3,700 Lakes Mail NSW Fairfax Media 27,100 12,800 14,300 7,900 8,700 10,500 3,400 4,200 5,200 4,400 4,500 5,400 The Post Weekly (Goulburn) NSW Fairfax Media 12,100 6,000 6,100 4,000 4,400 3,700 2,200 2,100 1,700 1,800 2,400 2,000 Bega District News NSW Fairfax Media 4,800 2,300 2,500 1,200 2,000 1,600 500 1,000 800 700 1,000 800 Blayney Chronicle NSW Fairfax Media 3,000 1,400 1,500 1,100 1,100 800 500 600 400 600 500 400 Braidwood Times NSW Fairfax Media 1,800 900 900 500 700 500 200 400 300 300 400 300 Cootamundra Herald -

Australian Associated Press Submission to the Senate Inquiry on the Treasury Laws Amendment (News Media and Digital Platforms Mandatory Bargaining Code) Bill 2020

AUSTRALIAN ASSOCIATED PRESS SUBMISSION TO THE SENATE INQUIRY ON THE TREASURY LAWS AMENDMENT (NEWS MEDIA AND DIGITAL PLATFORMS MANDATORY BARGAINING CODE) BILL 2020 Australian Associated Press (AAP) thanks the Senate for an opportunity to comment on the Treasury Laws Amendment (News Media and Digital Platforms Mandatory Bargaining Code) Bill 2020 (the Bill). The Treasurer has stated that “[t]he News Media and Digital Platforms Mandatory Bargaining Code is a world-leading initiative. It is designed to level the playing field and to ensure a sustainable and viable Australian media landscape. It's a key part of the government's strategy to ensure that the Australian economy is able to take full advantage of the benefits of digital technology, supported by appropriate regulation to protect key elements of Australian society. One such key element is a strong and sustainable Australian news media landscape.”1 AAP supports the Bill in its current form as it assists ‘retail’ media, that is, news media who have a direct-to-consumer “News Source” (as defined in the Bill), at a time when the industry is in a state of deep and prolonged crisis. However whilst the Bill helps AAP’s retail media customers, it does not contemplate a critical pillar of competition and media diversity in the news media industry in Australia - namely wholesale providers of news. One of the most important wholesale suppliers of news content in nearly every country is the national newswire. In Australia, this independent wholesale newswire service is fulfilled by AAP, which has been covering the news continuously for over 85 years. -

Thylacine Shistorical Society Has Been Working Hand in Hand with the Museum and Di Bricknell Tasmanian Tiger to Produce Wonderful Banners, Posters And

GLAMORGAN SPRING BAY HISTORICAL SOCIETY INC. issue 2 february 2012 22 Franklin Street dtp: d. bricknell Swansea TAS 7190 ☞ 6256 5077 FELLOW MEMBERS ince our opening in December 2011 our thylacine SHistorical Society has been working hand in hand with the museum and Di Bricknell Tasmanian Tiger to produce wonderful banners, posters and information for exhibitions. This can only he Thylacine (Thylacinus cynocephalus), also known Tas the Tasmanian Tiger, is one of the worlds enhance relations and get us ‘out there’ legendary animals. Despite its fame it is one of the least understood of Tasmania’s native fauna. European settlers feared it possibly because the stripes on its back resembled I’m pleased to report that society sales have those of a tiger. Within a century of white settlement fficially opened in December 2011 by blah b this carnivorous marsupial had been pushed to the been excellent especially Louisa Anne Meredith Obuilding... brink of extinction. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetuer adipiscinglah thee commodo, ipsum sed pharetra gravida, orci magna rho neque, id pulvinar odio lorem non turpis. Tasmanian Tigers roamed freely across most of the island cards and the Swansea Walk booklet. Our upfficially opened in December 2011 by blah blah the lit. Morbi building... Nullam sit amet enim. Suspendisse id velit vitae ligul ncusbut had a bad reputation and were considered sheep O condimentum. Aliquam erat volutpat. Sed q Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetuer adipiscing elit. Morbi facilisi. Nulla libero. Vivamus pharetra posuere killers. In 1888 the government offered a bounty of a volutpat and coming publication of Houses & Estates ofcommodo, ipsum sed pharetra gravida, orci magna rhoncus consectetuer. -

Limestone Coast Protection Alliance Inc

Limestone Coast Protection Alliance Inc. Save our water, soil and air from invasive mining & industrial gasfields www.protectlimestonecoast.org.au Email: [email protected] Senate Inquiry into the Landholders' Rights to Refuse (Gas and Coal) Bill 2015 May, 2015 Limestone Coast Protection Alliance Inc. Save our water, soil and air from invasive mining & industrial gasfields www.protectlimestonecoast.org.au Email: [email protected] Senate Inquiry into the Landholders' Rights to Refuse (Gas and Coal) Bill 2015 The private senator's bill proposes to make gas or coal mining activities undertaken without prior written authorisation from landholders unlawful and would ban constitutional corporations from engaging in hydraulic fracturing operations (fracking) for coal seam gas, shale gas and tight gas The Limestone Coast Protection Alliance offer our submission into this inquiry divided in the following sections. Section 1. Summary Section 2. The risks of groundwater contamination - part 1 Section 3. The risks of groundwater contamination - part 2 Section 4. Chemicals Section 5. The impacts upon landscape Section 6. The effectiveness of existing legislation and regulation Section 7. The potential net economic outcomes to the region and the rest of the State Section 8. Health Section 9. Renewable energy Contributors: Anne Daw Leanne Emery Heather Gibbons Heather Heggie Debbie Nulty Merilyn Paxton Dr Catherine Pye Dr David Senior Dennis Vice Sue Westgarth Sandra Young Committee: Huck Shepherd (Chairman), Merilyn Paxton (Deputy Chair), Heather Gibbons, Marcia Lorenz and Dr Catherine Pye (Secretarial), Anne Daw, Donna Kennett (Treasurer), Leanne Emery, Will Legoe, Debbie Nulty, Ernest Ralton, Dr David Senior, Dennis Vice, Sue Westgarth. -

NEWSLETTER ISSN 1443-4962 No

Four country newspaper offices in Western Australia, 10 to 12 years ago. Barry Blair, of Uralla, NSW, took the photo at top right and your editor the other three. Clockwise from top left: Avon Valley Advocate, Northam, 2003; Northern Guardian, Carnarvon, 2005; Manjimup-Bridgetown Times, Manjimup, 2003; and Kimberley Echo, Kununurra, 2005. AUSTRALIAN NEWSPAPER HISTORY GROUP NEWSLETTER ISSN 1443-4962 No. 85 December 2015 Publication details Compiled for the Australian Newspaper History Group by Rod Kirkpatrick, PO Box 8294 Mount Pleasant Qld 4740. Ph. +61-7-4942 7005. Email: [email protected]/ Contributing editor and founder: Victor Isaacs, of Canberra, is at [email protected]/ Back copies of the Newsletter and some ANHG publications can be viewed online at: http://www.amhd.info/anhg/index.php Deadline for the next Newsletter: 25 February 2016. Subscription details appear at end of Newsletter. [Number 1 appeared October 1999.] Ten issues had appeared by December 2000 and the Newsletter has since appeared five times a year. 1—Current Developments: National & Metropolitan 85.1.1 Herald Sun at 25 Melbourne’s Herald Sun published a special issue on 8 October to commemorate the 25th anniversary of the merging of the Herald estab. 1840) and the morning Sun News-Pictorial (1922). The issue featured a four page wrap-around including a front and back page cartoon summarising the events of the past 25 years, and a 24 page glossy colour magazine with a summary of events, including a very brief history of the Herald Sun. A book was published Herald Sun 25 Years of Pictures, 208 pages, hardback, $39.95 and $10 postage. -

International Newsstream (Proquest) Accurate As of 22 September 2018

Self Study Report 1 Part II: Standard 7. Resources, Facilities and Equipment The School’s research and teaching support resources are accessible in a number of ways across a variety of platforms. The resources at the University Library and the School of Communication Library are available to all professors and Communication students. Due to the damages caused to the School’s building, the School’s library is now located at the third floor of the University Library. The collection has been relocated to the same building where the academic community has a variety of areas where they can use computers, access the Internet and study, individually or with groups. Resources to students and faculty are available onsite and online. These resources include academic search engines and on-line databases, which are available both on-site and remotely. An extensive collection of mass communication, journalism, and social sciences journals are available through these databases. The following list includes the publications currently available through these databases: International Newsstream (ProQuest) Accurate as of 22 September 2018 Publication Full Text Full Text Title Country First Last Pub Language 6-Jun- 24X7 News Bahrain Online United States 2015 Current English 17-Jul- 16-Sep- 7.30 Australia 2003 2016 English 25-Dec- 7DAYS United States 2006 Current English 1-Jan- AAP Bulletin Wire Australia 2005 Current English 24-Nov- AAP Finance News Wire Australia 2004 Current English 24-Nov- AAP General News Wire Australia 2004 Current English 24-Nov- AAP -

News Themes on Regional Newspaper Front Pages Australian Journalism Review, 2017; 39(1):63-76

PUBLISHED VERSION Kathryn Bowd Keeping it local: news themes on regional newspaper front pages Australian Journalism Review, 2017; 39(1):63-76 Copyright of Australian Journalism Review is the property of Journalism Education & Research Association of Australia Inc and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use. PERMISSIONS http://www.jeaa.org.au/publications/ Email confirmation received 9 November 2015 & 6 September 2018. JERAA President has forwarded your query to me in my capacity as editor of Australian Journalism Review. I am pleased to advise that you are welcome to post the full text version of this article in Adelaide Research & Scholarship, the University of Adelaide’s institutional repository. 7 September 2018 http://hdl.handle.net/2440/114218 Keeping it local: news themes on regional newspaper front pages Kathryn Bowd Abstract Local news is fundamental to the activities of most regional newspapers in Australia. While “local” is a contested term, it has traditionally been used in the Australian regional news media context to refer to issues, events and people occurring or situated within the primary geographi- cal circulation area of a print newspaper. This emphasis on the local extends from what news outlets are reporting to how they report it – and the kinds of understandings they promote about what it means to be part of a regional community. The public-sphere role of such outlets means they are ideally placed to communicate to news audiences ideas about local identity and community.