Citylcounty Water and Wastewater Study Oversight

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Trail Inventory of U.S

The Trail Inventory of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Stations in Arizona Prepared By: Federal Highway Administration Central Federal Lands Highway Division March 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION PAGE 1. AZ STATE SUMMARY Table of Contents 1-1 List of Refuges 1-2 Mileage by Trail Class, Condition, and Surface 1-3 2-9. REFUGE SUMMARIES Mileage by Trail Class, Condition, and Surface X-1 Trail Location Map X-2 Trail Identification X-3 Condition and Deficiency Sheets X-4 Photographic Sheets X-5 10. APPENDIX Glossary of Terms and Abbreviations 10-1 Trail Classification System 10-4 1-1 FWS Stations in Arizona with Trails Station Name Trail Miles Chapter Bill Williams River NWR 0.27 2 Buenos Aires NWR 6.62 3 Cabeza Prieta NWR 0.16 4 Cibola NWR 0.91 5 Havasu NWR 0.22 6 Imperial NWR 1.31 7 Leslie Canyon NWR 1.47 8 San Bernardino NWR 2.39 9 1-2 Arizona NWR Trail and Summaries Trail Miles and Percentages by Surface Type and Condition Mileage by Trail Condition Total Trail Surface Excellent Good Fair Poor Very Poor Not Rated* Miles Type MILES % MILES % MILES % MILES % MILES % MILES % Native 7.91 59% 0.20 2% 0.32 2% 0% 0% 0% 8.43 Gravel 0.96 7% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0.96 Asphalt 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0.00 Concrete 0.27 2% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0.27 Turnpike 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0.00 Boardwalk 0.26 2% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0.26 Puncheon 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0.00 Woodchips 0.05 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0.05 Admin Road 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 3.36 25% 3.36 Other 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0.00 Totals 9.45 71% 0.20 2% 0.32 2% 0.00 0% 0.00 0% 3.36 25% 13.33 Trail Miles and Percentages by Trail Classification and Condition Mileage by Trail Condition Total Trail Excellent Good Fair Poor Very Poor Not Rated* Miles Classification MILES % MILES % MILES % MILES % MILES % MILES % TC1 2.60 20% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 2.60 TC2 1.88 14% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 1.88 TC3 1.04 8% 0% 0.32 2% 0% 0% 0.97 7% 2.33 TC4 3.61 27% 0.20 2% 0% 0% 0% 2.39 18% 6.20 TC5 0.32 2% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0.32 Totals 9.45 71% 0.20 2% 0.32 2% 0.00 0% 0.00 0% 3.36 25% 13.33 * Admin Roads are included in the inventory but are not rated for condition. -

USGS Open-File Report 2009-1269, Appendix 1

Appendix 1. Summary of location, basin, and hydrological-regime characteristics for U.S. Geological Survey streamflow-gaging stations in Arizona and parts of adjacent states that were used to calibrate hydrological-regime models [Hydrologic provinces: 1, Plateau Uplands; 2, Central Highlands; 3, Basin and Range Lowlands; e, value not present in database and was estimated for the purpose of model development] Average percent of Latitude, Longitude, Site Complete Number of Percent of year with Hydrologic decimal decimal Hydrologic altitude, Drainage area, years of perennial years no flow, Identifier Name unit code degrees degrees province feet square miles record years perennial 1950-2005 09379050 LUKACHUKAI CREEK NEAR 14080204 36.47750 109.35010 1 5,750 160e 5 1 20% 2% LUKACHUKAI, AZ 09379180 LAGUNA CREEK AT DENNEHOTSO, 14080204 36.85389 109.84595 1 4,985 414.0 9 0 0% 39% AZ 09379200 CHINLE CREEK NEAR MEXICAN 14080204 36.94389 109.71067 1 4,720 3,650.0 41 0 0% 15% WATER, AZ 09382000 PARIA RIVER AT LEES FERRY, AZ 14070007 36.87221 111.59461 1 3,124 1,410.0 56 56 100% 0% 09383200 LEE VALLEY CR AB LEE VALLEY RES 15020001 33.94172 109.50204 1 9,440e 1.3 6 6 100% 0% NR GREER, AZ. 09383220 LEE VALLEY CREEK TRIBUTARY 15020001 33.93894 109.50204 1 9,440e 0.5 6 0 0% 49% NEAR GREER, ARIZ. 09383250 LEE VALLEY CR BL LEE VALLEY RES 15020001 33.94172 109.49787 1 9,400e 1.9 6 6 100% 0% NR GREER, AZ. 09383400 LITTLE COLORADO RIVER AT GREER, 15020001 34.01671 109.45731 1 8,283 29.1 22 22 100% 0% ARIZ. -

Environmental Flows and Water Demands in Arizona

Environmental Flows and Water A University of Arizona Water Resources Research Center Project Demands in Arizona ater is an increasingly scarce resource and is essential for Arizona’s future. Figure 1. Elements of Environmental Flow WWith Arizona’s population growth and Occurring in Seasonal Hydrographs continued drought, citizens and water managers have been taking a closer look at water supplies in the state. Municipal, industrial, and agricul- tural water users are well-represented demand sectors, but water supplies and management to benefit the environment are not often consid- ered. This bulletin explains environmental water demands in Arizona and introduces information essential for considering environmental water demands in water management discussions. Considering water for the environment is impor- tant because humans have an interconnected and interdependent relationship with the envi- ronment. Nature provides us recreation oppor- tunities, economic benefits, and water supplies Data Source: to sustain our communities. USGS stream gage data Figure 2: Human Demand and Current Flow in Arizona Environmental water demands (or environmental flow) (circle size indicates relative amount of water) refers to how much water is needed in a watercourse to sustain a healthy ecosystem. Defining environmental water demand goes beyond the ecology and hydrol- Maximum ogy of a system and should include consideration for Flows how much water is required to achieve an agreed Industrial 40.8 maf Industrial SW Municipal upon level of river health, as determined by the GW 1% GW 8% water-using community. Arizona’s native ani- 4% mals and plants depend upon dynamic flows commonly described according to the natural Municipal SW flow regime. -

PETRIFIED FOREST: a Playground for Wildlife Baseball’S Back!

Spring PETRIFIED FOREST: A Playground for Wildlife Baseball’s Back! arizonahighways.com march 2003 MARCH 2003 page 50 COVER NATURE 55 GENE PERRET’S WIT STOP 6 14 If you’d like a good Surprise, drive northwest of Survival in the Grasslands A Bevy of Blooms Phoenix — and don’t ask Why. Preserving masked bobwhite quail and and Butterflies pronghorn antelope also rebuilds the habitat 44 HUMOR at Buenos Aires National Wildlife Refuge. Delicate-winged beauties and dazzling floral displays await at the Phoenix Desert Botanical 2 LETTERS AND E-MAIL Garden’s Butterfly Pavilion. 22 PORTFOLIO 46 DESTINATION Arizona’s in Love with INDIANS Lowell Observatory 18 Visitors get telescope time, too, at this noted Baseball Spring Training Butterfly Myths institution, home to 27 full-time astronomers doing pioneering research. The Cactus League’s 10 major league teams The gentle, fluttering insects take on varied have a devoted following, including visitors symbolic roles in many Indian cultures. 3 TAKING THE OFF-RAMP from out of state. Explore Arizona oddities, attractions and pleasures. HISTORY TRAVEL 32 54 EXPERIENCE ARIZONA 38 Hike a Historic Trail Go on a hike or pan for gold in Apache Junction to Life in a Stony Landscape Retrace the southern Arizona route of Spain’s commemorate treasure hunting in the Superstition Come spring, the Petrified Forest National Juan Bautista de Anza, who led the 18th-century Mountains; help the Tohono O’odham Indians celebrate Park is abuzz with critters and new plants. colonization of San Francisco. their heritage and see their arts and crafts in Ajo; and enjoy the re-enactment of mountain man skills in Oatman. -

Arizona – May/June 2017 Sjef Öllers

Arizona – May/June 2017 Sjef Öllers Our first holiday in the USA was a relaxed trip with about equal time spent on mammalwatching, birding and hiking, but often all three could be combined. Mammal highlights included White-nosed Coati, Hooded Skunk, Striped Skunk, American Badger and unfortunately brief views of Black-footed Ferret. There were many birding highlights but I was particularly pleased with sightings of Montezuma Quail, Scaled Quail, Red-faced Warbler, Elegant Trogon, Greater Roadrunner, Elf Owl, Spotted Owl, Dusky Grouse and Californian Condor. American Badger Introduction Arizona seemed to offer a good introduction to both the avian and mammalian delights of North America. Our initial plan was to do a comprehensive two-week visit of southeast Arizona, but after some back and forth we decided to include a visit to the Grand Canyon, also because this allowed a visit to Seligman for Badger and Black-footed Ferret and Vermillion Cliffs for Californian Condor. Overall, the schedule worked out pretty well, even if the second part included a lot more driving, although most of the driving was through pleasant or even superb scenery. I was already a little skeptical of including Sedona before the trip, and while I don’t regret having visited the Sedona area, from a mammal and birding perspective it is a destination that could be excluded. Another night in Seligman and more hiking/birding around Flagstaff would probably have been more productive. 1 Timing and Weather By late May/early June the northbound migratory species have largely left southeast Arizona so you mainly get to see the resident birds and summer visitors. -

Eyec Sail Dzan

Desert Plants, Volume 6, Number 3 (1984) Item Type Article Authors Hendrickson, Dean A.; Minckley, W. L. Publisher University of Arizona (Tucson, AZ) Journal Desert Plants Rights Copyright © Arizona Board of Regents. The University of Arizona. Download date 27/09/2021 19:02:02 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/552226 Desert Volume 6. Number 3. 1984. (Issued early 1985) Published by The University of Arizona at the Plants Boyce Thompson Southwestern Arboretum eyec sail Dzan Ciénegas Vanishing Climax Communities of the American Southwest Dean A. Hendrickson and W. L. Minckley O'Donnell Ciénega in Arizona's upper San Pedro basin, now in the Canelo Hills Ciénega Preserve of the Nature Conservancy. Ciénegas of the American Southwest have all but vanished due to environmental changes brought about by man. Being well- watered sites surrounded by dry lands variously classified as "desert," "arid," or "semi- arid," they were of extreme importance to pre- historic and modern Homo sapiens, animals and plants of the Desert Southwest. Photograph by Fritz jandrey. 130 Desert Plants 6(3) 1984 (issued early 1985) Desert Plants Volume 6. Number 3. (Issued early 1985) Published by The University of Arizona A quarterly journal devoted to broadening knowledge of plants indigenous or adaptable to arid and sub -arid regions, P.O. Box AB, Superior, Arizona 85273 to studying the growth thereof and to encouraging an appre- ciation of these as valued components of the landscape. The Boyce Thompson Southwestern Arboretum at Superior, Arizona, is sponsored by The Arizona State Parks Board, The Boyce Thompson Southwestern Arboretum, Inc., and The University of Arizona Frank S. -

Native Fish Restoration in Redrock Canyon

U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Final Environmental Assessment Phoenix Area Office NATIVE FISH RESTORATION IN REDROCK CANYON U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service Southwestern Region Coronado National Forest Santa Cruz County, Arizona June 2008 Bureau of Reclamation Finding of No Significant Impact U.S. Forest Service Finding of No Significant Impact Decision Notice INTRODUCTION In accordance with the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (Public Law 91-190, as amended), the Bureau of Reclamation (Reclamation), as the lead Federal agency, and the Forest Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), and Arizona Game and Fish Department (AGFD), as cooperating agencies, have issued the attached final environmental assessment (EA) to disclose the potential environmental impacts resulting from construction of a fish barrier, removal of nonnative fishes with the piscicide antimycin A and/or rotenone, and restoration of native fishes and amphibians in Redrock Canyon on the Coronado National Forest (CNF). The Proposed Action is intended to improve the recovery status of federally listed fish and amphibians (Gila chub, Gila topminnow, Chiricahua leopard frog, and Sonora tiger salamander) and maintain a healthy native fishery in Redrock Canyon consistent with the CNF Plan and ongoing Endangered Species Act (ESA), Section 7(a)(2), consultation between Reclamation and the FWS. BACKGROUND The Proposed Action is part of a larger program being implemented by Reclamation to construct a series of fish barriers within the Gila River Basin to prevent the invasion of nonnative fishes into high-priority streams occupied by imperiled native fishes. This program is mandated by a FWS biological opinion on impacts of Central Arizona Project (CAP) water transfers to the Gila River Basin (FWS 2008a). -

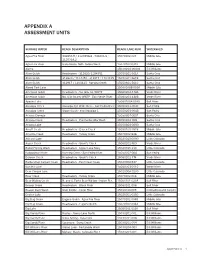

Appendix a Assessment Units

APPENDIX A ASSESSMENT UNITS SURFACE WATER REACH DESCRIPTION REACH/LAKE NUM WATERSHED Agua Fria River 341853.9 / 1120358.6 - 341804.8 / 15070102-023 Middle Gila 1120319.2 Agua Fria River State Route 169 - Yarber Wash 15070102-031B Middle Gila Alamo 15030204-0040A Bill Williams Alum Gulch Headwaters - 312820/1104351 15050301-561A Santa Cruz Alum Gulch 312820 / 1104351 - 312917 / 1104425 15050301-561B Santa Cruz Alum Gulch 312917 / 1104425 - Sonoita Creek 15050301-561C Santa Cruz Alvord Park Lake 15060106B-0050 Middle Gila American Gulch Headwaters - No. Gila Co. WWTP 15060203-448A Verde River American Gulch No. Gila County WWTP - East Verde River 15060203-448B Verde River Apache Lake 15060106A-0070 Salt River Aravaipa Creek Aravaipa Cyn Wilderness - San Pedro River 15050203-004C San Pedro Aravaipa Creek Stowe Gulch - end Aravaipa C 15050203-004B San Pedro Arivaca Cienega 15050304-0001 Santa Cruz Arivaca Creek Headwaters - Puertocito/Alta Wash 15050304-008 Santa Cruz Arivaca Lake 15050304-0080 Santa Cruz Arnett Creek Headwaters - Queen Creek 15050100-1818 Middle Gila Arrastra Creek Headwaters - Turkey Creek 15070102-848 Middle Gila Ashurst Lake 15020015-0090 Little Colorado Aspen Creek Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-769 Verde River Babbit Spring Wash Headwaters - Upper Lake Mary 15020015-210 Little Colorado Babocomari River Banning Creek - San Pedro River 15050202-004 San Pedro Bannon Creek Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-774 Verde River Barbershop Canyon Creek Headwaters - East Clear Creek 15020008-537 Little Colorado Bartlett Lake 15060203-0110 Verde River Bear Canyon Lake 15020008-0130 Little Colorado Bear Creek Headwaters - Turkey Creek 15070102-046 Middle Gila Bear Wallow Creek N. and S. Forks Bear Wallow - Indian Res. -

STREAMS in the DESERT Summary of Theme Some 90 Miles Of

Interpretive Themes and Related Resources 89 STREAMS IN THE DESERT Summary of Theme Some 90 miles of streams and rivers flow year-round in the Santa Cruz watershed. These support riparian habitats that are both beautiful and the keys to life in the desert. The word “riparian” describes the banks of streams and rivers, and the distinct plants and animals found there. At lower elevations, riparian habitats are dominated by big, billowing willow and cottonwood trees. At higher elevations, these are joined by hackberry, sycamore, ash, walnut, alder, and other trees. In dry regions such as southern Arizona, certain plants are found only in the moist conditions along streams and rivers. Some animals that roam mountains and deserts depend on visits to riparian areas, where they can rest, drink, and sometimes hunt. Other animals spend their entire lives in riparian areas and cannot survive without them. These include many fish, frogs, and bird species. Some 60-75 percent of all wildlife species in this region depend on riparian areas at some point in their lives, and 90 percent of all bird species are found in these desert oases. Riparian areas also function as movement or migration corridors for wildlife. North-south trending rivers such as the Santa Cruz are important migratory routes for birds. Description of Theme Riparian Areas Riparian communities are those ribbons of life along banks of rivers, shoreline communities along slow or non-flowing waters such as marshes and lakes, and along the banks of dry washes in deserts. Riparian communities have three components: water availability, vegetation, and wildlife. -

Searching for the Hopi Center of Creation

searching for the hopi center of creation arizonahighways.com APRIL 2003 SacredSacred Vistas Vistas Navajo ofof thethe going up Young Rock Climbers Face Their Fears Verde ValleyRiver Paradise Paradise a bounty of birds Hassayampa A Peaceful Waterfront Retreat Rattlesnake Grease and Cockroach Tea frontier medicine APRIL 2003 COVER/PORTFOLIO 20 Magnificent Navajoland page 50 The stories and glorious beauty of this vast terrain tell of a proud Indian heritage. 55 GENE PERRET’S WIT STOP Arizona’s state mammal — the ringtail, or cacomistle — was a favorite pet of lonely old miners. ADVENTURE 6 Rugged Hike to Sipapu 44 HUMOR It’s no easy trek to Blue Spring and the 2 LETTERS AND E-MAIL sacred Hopi site called Sipapu on the Little Colorado River. 46 DESTINATION Hassayampa River Preserve The beautiful variety of natural wonders might 36 HISTORY even have appealed to artist Claude Monet. Medicine on 3 TAKING THE OFF-RAMP Arizona’s Frontier Explore Arizona oddities, attractions and pleasures. Territorial physicians were mostly brave U.S. 54 EXPERIENCE ARIZONA Army surgeons doubling as naturalists, A birding and nature festival flies into Yuma; the bookkeepers, weathermen and gardeners. world’s largest outdoor Easter pageant unfolds in Mesa; Miami celebrates its mining history; and Arizona 40 TRAVEL commemorates its Asian pioneers in Phoenix. Finding Courage in the Rocks 49 ALONG THE WAY Young climbers triumph over their fears as they What’s really behind a place name? It’s not always challenge the cliffs of Queen Creek Canyon. what you’d think. 50 BACK ROAD ADVENTURE BIRDS Ruby Road to Buenos Aires 14 National Wildlife Refuge Flocking to Verde Valley Woodlands, small lakes, grasslands and a chance The birds know it’s all about ideal location in to see wildlife mark this 50-mile drive. -

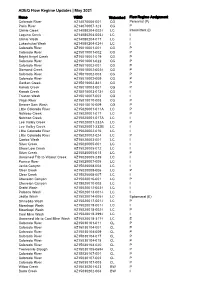

ADEQ Flow Regime Updates | May 2021

ADEQ Flow Regime Updates | May 2021 Name WBID Watershed Flow Regime Assignment Colorado River AZ14070006-001 CG Perennial (P) Paria River AZ14070007-123 CG P Chinle Creek AZ14080204-002-I LC Intermittent (I) Laguna Creek AZ14080204-003-I LC I Chinle Wash AZ14080204-017 LC I Lukachukai Wash AZ14080204-024-I LC I Colorado River AZ15010001-001 CG P Colorado River AZ15010001-002 CG P Bright Angel Creek AZ15010001-019 CG P Colorado River AZ15010001-022 CG P Colorado River AZ15010002-001 CG P Diamond Creek AZ15010002-002-I CG P Colorado River AZ15010002-003 CG P Colorado River AZ15010002-009 CG P Garden Creek AZ15010002-841 CG P Kanab Creek AZ15010003-001 CG P Kanab Creek AZ15010003-013-I CG I Truxton Wash AZ15010007-002 CG I Virgin River AZ15010010-003 CG P Beaver Dam Wash AZ15010010-009 CG P Little Colorado River AZ15020001-011A LC P Nutrioso Creek AZ15020001-017 LC P Nutrioso Creek AZ15020001-017A LC I Lee Valley Creek AZ15020001-232A LC P Lee Valley Creek AZ15020001-232B LC I Little Colorado River AZ15020002-016 LC I Little Colorado River AZ15020002-024 LC P Carrizo Wash AZ15020003-001 LC I Silver Creek AZ15020005-001 LC I Show Low Creek AZ15020005-012 LC I Silver Creek AZ15020005-013 LC P Unnamed Trib to Walnut Creek AZ15020005-239 LC I Puerco River AZ15020007-005 LC I Jacks Canyon AZ15020008-004 LC I Clear Creek AZ15020008-006 LC P Clear Creek AZ15020008-007 LC I Chevelon Canyon AZ15020010-001 LC P Chevelon Canyon AZ15020010-003 LC I Oraibi Wash AZ15020012-003-I LC I Polacca Wash AZ15020013-001-I LC I Jadito Wash AZ15020014-005-I LC Ephemeral -

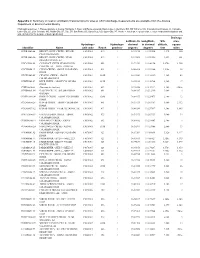

USGS Open-File Report 2009-1269, Appendix 2

Appendix 2. Summary of location and basin characteristics for sites at which discharge measurements are available from the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality [Hydrologic provinces: 1, Plateau Uplands; 2, Central Highlands; 3, Basin and Range Lowlands. Basin codes in Identifiers: BW, Bill Williams; CG, Colorado-Grand Canyon; Cl, Colorado- Lower Gila; LC, Little Colorado; MG, Middle Gila; SR, Salt; SP, San Pedro; SC, Santa Cruz; UG, Upper Gila; VR, Verde. <, less than; >, greater than; e, value not present in database and was estimated for the purpose of model predictions] Drainage Latitude, in Longitude, Site area, Hydrologic Hydrologic decimal in decimal altitude, square Identifier Name unit code Reach province degrees degrees feet miles CGBRA000.44 BRIGHT ANGEL CREEK - BELOW 15010001 019 1 36.10236 112.09514 2,520 100 PHANTOM RANCH CGBRA000.50 BRIGHT ANGEL CREEK - NEAR 15010001 019 1 36.10306 112.09556 2,452 101 GRAND CANYON, AZ CGCAT056.68 CATARACT CREEK NEAR GRAND 15010004 005 1 35.72333 112.44194 5,470e 1,200 CANYON, AZ USGS 09404100 CGCLE000.19 CLEAR CREEK - ABOVE COLORADO 15010001 025 1 36.08414 112.03344 2,520e 36 RIVER CGCRY000.05 CRYSTAL CREEK - ABOVE 15010002 018B 1 36.13542 112.24319 2,360 43 COLORADO RIVER CGDEE000.07 DEER CREEK - ABOVE COLORADO 15010002 019B 1 36.38931 112.50764 1,960 17 RIVER CGDIA000.06 (No name in database) 15010002 002 1 35.76556 113.37222 1,340 <946e CGGDN001.09 GARGEN CREEK - BELOW INDIAN 15010002 841 1 36.08347 112.12319 3,600 4 GARDEN CGHRM000.08 HERMIT CREEK - ABOVE COLORADO 15010002 020B