Historical and Current Status of the Western Yellow-Billed Cuckoo Excerpted from October 2013 Proposed Listing Rule and Updated by the YBCU Core Team

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Trail Inventory of U.S

The Trail Inventory of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Stations in Arizona Prepared By: Federal Highway Administration Central Federal Lands Highway Division March 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION PAGE 1. AZ STATE SUMMARY Table of Contents 1-1 List of Refuges 1-2 Mileage by Trail Class, Condition, and Surface 1-3 2-9. REFUGE SUMMARIES Mileage by Trail Class, Condition, and Surface X-1 Trail Location Map X-2 Trail Identification X-3 Condition and Deficiency Sheets X-4 Photographic Sheets X-5 10. APPENDIX Glossary of Terms and Abbreviations 10-1 Trail Classification System 10-4 1-1 FWS Stations in Arizona with Trails Station Name Trail Miles Chapter Bill Williams River NWR 0.27 2 Buenos Aires NWR 6.62 3 Cabeza Prieta NWR 0.16 4 Cibola NWR 0.91 5 Havasu NWR 0.22 6 Imperial NWR 1.31 7 Leslie Canyon NWR 1.47 8 San Bernardino NWR 2.39 9 1-2 Arizona NWR Trail and Summaries Trail Miles and Percentages by Surface Type and Condition Mileage by Trail Condition Total Trail Surface Excellent Good Fair Poor Very Poor Not Rated* Miles Type MILES % MILES % MILES % MILES % MILES % MILES % Native 7.91 59% 0.20 2% 0.32 2% 0% 0% 0% 8.43 Gravel 0.96 7% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0.96 Asphalt 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0.00 Concrete 0.27 2% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0.27 Turnpike 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0.00 Boardwalk 0.26 2% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0.26 Puncheon 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0.00 Woodchips 0.05 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0.05 Admin Road 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 3.36 25% 3.36 Other 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0.00 Totals 9.45 71% 0.20 2% 0.32 2% 0.00 0% 0.00 0% 3.36 25% 13.33 Trail Miles and Percentages by Trail Classification and Condition Mileage by Trail Condition Total Trail Excellent Good Fair Poor Very Poor Not Rated* Miles Classification MILES % MILES % MILES % MILES % MILES % MILES % TC1 2.60 20% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 2.60 TC2 1.88 14% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 1.88 TC3 1.04 8% 0% 0.32 2% 0% 0% 0.97 7% 2.33 TC4 3.61 27% 0.20 2% 0% 0% 0% 2.39 18% 6.20 TC5 0.32 2% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0.32 Totals 9.45 71% 0.20 2% 0.32 2% 0.00 0% 0.00 0% 3.36 25% 13.33 * Admin Roads are included in the inventory but are not rated for condition. -

USGS Open-File Report 2009-1269, Appendix 1

Appendix 1. Summary of location, basin, and hydrological-regime characteristics for U.S. Geological Survey streamflow-gaging stations in Arizona and parts of adjacent states that were used to calibrate hydrological-regime models [Hydrologic provinces: 1, Plateau Uplands; 2, Central Highlands; 3, Basin and Range Lowlands; e, value not present in database and was estimated for the purpose of model development] Average percent of Latitude, Longitude, Site Complete Number of Percent of year with Hydrologic decimal decimal Hydrologic altitude, Drainage area, years of perennial years no flow, Identifier Name unit code degrees degrees province feet square miles record years perennial 1950-2005 09379050 LUKACHUKAI CREEK NEAR 14080204 36.47750 109.35010 1 5,750 160e 5 1 20% 2% LUKACHUKAI, AZ 09379180 LAGUNA CREEK AT DENNEHOTSO, 14080204 36.85389 109.84595 1 4,985 414.0 9 0 0% 39% AZ 09379200 CHINLE CREEK NEAR MEXICAN 14080204 36.94389 109.71067 1 4,720 3,650.0 41 0 0% 15% WATER, AZ 09382000 PARIA RIVER AT LEES FERRY, AZ 14070007 36.87221 111.59461 1 3,124 1,410.0 56 56 100% 0% 09383200 LEE VALLEY CR AB LEE VALLEY RES 15020001 33.94172 109.50204 1 9,440e 1.3 6 6 100% 0% NR GREER, AZ. 09383220 LEE VALLEY CREEK TRIBUTARY 15020001 33.93894 109.50204 1 9,440e 0.5 6 0 0% 49% NEAR GREER, ARIZ. 09383250 LEE VALLEY CR BL LEE VALLEY RES 15020001 33.94172 109.49787 1 9,400e 1.9 6 6 100% 0% NR GREER, AZ. 09383400 LITTLE COLORADO RIVER AT GREER, 15020001 34.01671 109.45731 1 8,283 29.1 22 22 100% 0% ARIZ. -

Environmental Flows and Water Demands in Arizona

Environmental Flows and Water A University of Arizona Water Resources Research Center Project Demands in Arizona ater is an increasingly scarce resource and is essential for Arizona’s future. Figure 1. Elements of Environmental Flow WWith Arizona’s population growth and Occurring in Seasonal Hydrographs continued drought, citizens and water managers have been taking a closer look at water supplies in the state. Municipal, industrial, and agricul- tural water users are well-represented demand sectors, but water supplies and management to benefit the environment are not often consid- ered. This bulletin explains environmental water demands in Arizona and introduces information essential for considering environmental water demands in water management discussions. Considering water for the environment is impor- tant because humans have an interconnected and interdependent relationship with the envi- ronment. Nature provides us recreation oppor- tunities, economic benefits, and water supplies Data Source: to sustain our communities. USGS stream gage data Figure 2: Human Demand and Current Flow in Arizona Environmental water demands (or environmental flow) (circle size indicates relative amount of water) refers to how much water is needed in a watercourse to sustain a healthy ecosystem. Defining environmental water demand goes beyond the ecology and hydrol- Maximum ogy of a system and should include consideration for Flows how much water is required to achieve an agreed Industrial 40.8 maf Industrial SW Municipal upon level of river health, as determined by the GW 1% GW 8% water-using community. Arizona’s native ani- 4% mals and plants depend upon dynamic flows commonly described according to the natural Municipal SW flow regime. -

PETRIFIED FOREST: a Playground for Wildlife Baseball’S Back!

Spring PETRIFIED FOREST: A Playground for Wildlife Baseball’s Back! arizonahighways.com march 2003 MARCH 2003 page 50 COVER NATURE 55 GENE PERRET’S WIT STOP 6 14 If you’d like a good Surprise, drive northwest of Survival in the Grasslands A Bevy of Blooms Phoenix — and don’t ask Why. Preserving masked bobwhite quail and and Butterflies pronghorn antelope also rebuilds the habitat 44 HUMOR at Buenos Aires National Wildlife Refuge. Delicate-winged beauties and dazzling floral displays await at the Phoenix Desert Botanical 2 LETTERS AND E-MAIL Garden’s Butterfly Pavilion. 22 PORTFOLIO 46 DESTINATION Arizona’s in Love with INDIANS Lowell Observatory 18 Visitors get telescope time, too, at this noted Baseball Spring Training Butterfly Myths institution, home to 27 full-time astronomers doing pioneering research. The Cactus League’s 10 major league teams The gentle, fluttering insects take on varied have a devoted following, including visitors symbolic roles in many Indian cultures. 3 TAKING THE OFF-RAMP from out of state. Explore Arizona oddities, attractions and pleasures. HISTORY TRAVEL 32 54 EXPERIENCE ARIZONA 38 Hike a Historic Trail Go on a hike or pan for gold in Apache Junction to Life in a Stony Landscape Retrace the southern Arizona route of Spain’s commemorate treasure hunting in the Superstition Come spring, the Petrified Forest National Juan Bautista de Anza, who led the 18th-century Mountains; help the Tohono O’odham Indians celebrate Park is abuzz with critters and new plants. colonization of San Francisco. their heritage and see their arts and crafts in Ajo; and enjoy the re-enactment of mountain man skills in Oatman. -

Gila Topminnow Revised Recovery Plan December 1998

GILA TOPMINNOW, Poeciliopsis occidentalis occidentalis, REVISED RECOVERY PLAN (Original Approval: March 15, 1984) Prepared by David A. Weedman Arizona Game and Fish Department Phoenix, Arizona for Region 2 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Albuquerque, New Mexico December 1998 Approved: Regional Director, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Date: Gila Topminnow Revised Recovery Plan December 1998 DISCLAIMER Recovery plans delineate reasonable actions required to recover and protect the species. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) prepares the plans, sometimes with the assistance of recovery teams, contractors, State and Federal Agencies, and others. Objectives are attained and any necessary funds made available subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved, as well as the need to address other priorities. Time and costs provided for individual tasks are estimates only, and not to be taken as actual or budgeted expenditures. Recovery plans do not necessarily represent the views nor official positions or approval of any persons or agencies involved in the plan formulation, other than the Service. They represent the official position of the Service only after they have been signed by the Regional Director or Director as approved. Approved recovery plans are subject to modification as dictated by new findings, changes in species status, and the completion of recovery tasks. ii Gila Topminnow Revised Recovery Plan December 1998 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Original preparation of the revised Gila topminnow Recovery Plan (1994) was done by Francisco J. Abarca 1, Brian E. Bagley, Dean A. Hendrickson 1 and Jeffrey R. Simms 1. That document was modified to this current version and the work conducted by those individuals is greatly appreciated and now acknowledged. -

Arizona – May/June 2017 Sjef Öllers

Arizona – May/June 2017 Sjef Öllers Our first holiday in the USA was a relaxed trip with about equal time spent on mammalwatching, birding and hiking, but often all three could be combined. Mammal highlights included White-nosed Coati, Hooded Skunk, Striped Skunk, American Badger and unfortunately brief views of Black-footed Ferret. There were many birding highlights but I was particularly pleased with sightings of Montezuma Quail, Scaled Quail, Red-faced Warbler, Elegant Trogon, Greater Roadrunner, Elf Owl, Spotted Owl, Dusky Grouse and Californian Condor. American Badger Introduction Arizona seemed to offer a good introduction to both the avian and mammalian delights of North America. Our initial plan was to do a comprehensive two-week visit of southeast Arizona, but after some back and forth we decided to include a visit to the Grand Canyon, also because this allowed a visit to Seligman for Badger and Black-footed Ferret and Vermillion Cliffs for Californian Condor. Overall, the schedule worked out pretty well, even if the second part included a lot more driving, although most of the driving was through pleasant or even superb scenery. I was already a little skeptical of including Sedona before the trip, and while I don’t regret having visited the Sedona area, from a mammal and birding perspective it is a destination that could be excluded. Another night in Seligman and more hiking/birding around Flagstaff would probably have been more productive. 1 Timing and Weather By late May/early June the northbound migratory species have largely left southeast Arizona so you mainly get to see the resident birds and summer visitors. -

Eyec Sail Dzan

Desert Plants, Volume 6, Number 3 (1984) Item Type Article Authors Hendrickson, Dean A.; Minckley, W. L. Publisher University of Arizona (Tucson, AZ) Journal Desert Plants Rights Copyright © Arizona Board of Regents. The University of Arizona. Download date 27/09/2021 19:02:02 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/552226 Desert Volume 6. Number 3. 1984. (Issued early 1985) Published by The University of Arizona at the Plants Boyce Thompson Southwestern Arboretum eyec sail Dzan Ciénegas Vanishing Climax Communities of the American Southwest Dean A. Hendrickson and W. L. Minckley O'Donnell Ciénega in Arizona's upper San Pedro basin, now in the Canelo Hills Ciénega Preserve of the Nature Conservancy. Ciénegas of the American Southwest have all but vanished due to environmental changes brought about by man. Being well- watered sites surrounded by dry lands variously classified as "desert," "arid," or "semi- arid," they were of extreme importance to pre- historic and modern Homo sapiens, animals and plants of the Desert Southwest. Photograph by Fritz jandrey. 130 Desert Plants 6(3) 1984 (issued early 1985) Desert Plants Volume 6. Number 3. (Issued early 1985) Published by The University of Arizona A quarterly journal devoted to broadening knowledge of plants indigenous or adaptable to arid and sub -arid regions, P.O. Box AB, Superior, Arizona 85273 to studying the growth thereof and to encouraging an appre- ciation of these as valued components of the landscape. The Boyce Thompson Southwestern Arboretum at Superior, Arizona, is sponsored by The Arizona State Parks Board, The Boyce Thompson Southwestern Arboretum, Inc., and The University of Arizona Frank S. -

Native Fish Restoration in Redrock Canyon

U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Final Environmental Assessment Phoenix Area Office NATIVE FISH RESTORATION IN REDROCK CANYON U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service Southwestern Region Coronado National Forest Santa Cruz County, Arizona June 2008 Bureau of Reclamation Finding of No Significant Impact U.S. Forest Service Finding of No Significant Impact Decision Notice INTRODUCTION In accordance with the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (Public Law 91-190, as amended), the Bureau of Reclamation (Reclamation), as the lead Federal agency, and the Forest Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), and Arizona Game and Fish Department (AGFD), as cooperating agencies, have issued the attached final environmental assessment (EA) to disclose the potential environmental impacts resulting from construction of a fish barrier, removal of nonnative fishes with the piscicide antimycin A and/or rotenone, and restoration of native fishes and amphibians in Redrock Canyon on the Coronado National Forest (CNF). The Proposed Action is intended to improve the recovery status of federally listed fish and amphibians (Gila chub, Gila topminnow, Chiricahua leopard frog, and Sonora tiger salamander) and maintain a healthy native fishery in Redrock Canyon consistent with the CNF Plan and ongoing Endangered Species Act (ESA), Section 7(a)(2), consultation between Reclamation and the FWS. BACKGROUND The Proposed Action is part of a larger program being implemented by Reclamation to construct a series of fish barriers within the Gila River Basin to prevent the invasion of nonnative fishes into high-priority streams occupied by imperiled native fishes. This program is mandated by a FWS biological opinion on impacts of Central Arizona Project (CAP) water transfers to the Gila River Basin (FWS 2008a). -

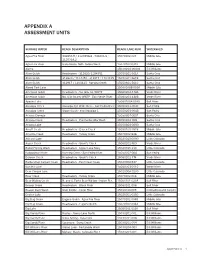

Appendix a Assessment Units

APPENDIX A ASSESSMENT UNITS SURFACE WATER REACH DESCRIPTION REACH/LAKE NUM WATERSHED Agua Fria River 341853.9 / 1120358.6 - 341804.8 / 15070102-023 Middle Gila 1120319.2 Agua Fria River State Route 169 - Yarber Wash 15070102-031B Middle Gila Alamo 15030204-0040A Bill Williams Alum Gulch Headwaters - 312820/1104351 15050301-561A Santa Cruz Alum Gulch 312820 / 1104351 - 312917 / 1104425 15050301-561B Santa Cruz Alum Gulch 312917 / 1104425 - Sonoita Creek 15050301-561C Santa Cruz Alvord Park Lake 15060106B-0050 Middle Gila American Gulch Headwaters - No. Gila Co. WWTP 15060203-448A Verde River American Gulch No. Gila County WWTP - East Verde River 15060203-448B Verde River Apache Lake 15060106A-0070 Salt River Aravaipa Creek Aravaipa Cyn Wilderness - San Pedro River 15050203-004C San Pedro Aravaipa Creek Stowe Gulch - end Aravaipa C 15050203-004B San Pedro Arivaca Cienega 15050304-0001 Santa Cruz Arivaca Creek Headwaters - Puertocito/Alta Wash 15050304-008 Santa Cruz Arivaca Lake 15050304-0080 Santa Cruz Arnett Creek Headwaters - Queen Creek 15050100-1818 Middle Gila Arrastra Creek Headwaters - Turkey Creek 15070102-848 Middle Gila Ashurst Lake 15020015-0090 Little Colorado Aspen Creek Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-769 Verde River Babbit Spring Wash Headwaters - Upper Lake Mary 15020015-210 Little Colorado Babocomari River Banning Creek - San Pedro River 15050202-004 San Pedro Bannon Creek Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-774 Verde River Barbershop Canyon Creek Headwaters - East Clear Creek 15020008-537 Little Colorado Bartlett Lake 15060203-0110 Verde River Bear Canyon Lake 15020008-0130 Little Colorado Bear Creek Headwaters - Turkey Creek 15070102-046 Middle Gila Bear Wallow Creek N. and S. Forks Bear Wallow - Indian Res. -

Flood Insurance Study Vol. 1

SANTA CRUZ COUNTY, ARIZONA AND INCORPORATED AREAS VOLUME 1 OF 3 Community Community Name Number SANTA CRUZ COUNTY, (UNINCORPORATED AREAS) 040090 NOGALES, CITY OF 040091 PATAGONIA, TOWN OF 040092 Santa Cruz County EFFECTIVE: DECEMBER 2, 2011 Federal Emergency Management Agency FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY NUMBER 04023CV001A NOTICE TO FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY USERS Communities participating in the National Flood Insurance Program have established repositories of flood hazard data for floodplain management and flood insurance purposes. This Flood Insurance Study (FIS) may not contain all data available within the repository. Please contact the Community Map Repository for any additional data. Part or all of this FIS may be revised and republished at any time. In addition, part of this FIS report may be revised by the Letter of Map Revision process, which does not involve republication or redistribution of the FIS report. It is, therefore, the responsibility of the user to consult with community officials and to check the community repository to obtain the most current FIS report components. Selected Flood Insurance Rate Map (FIRM) panels for this community contain information that was previously shown separately on the corresponding Flood Boundary and Floodway Map (FBFM) panels (e.g., floodways, cross sections). In addition, former flood hazard zone designations have been changed as follows: Old Zone(s) New Zone A1 through A30 AE B X C X Initial Countywide FIS Report Effective Date: December 2, 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS – VOLUME 1 Page 1.0 INTRODUCTION -

Feasibility Study for the SANTA CRUZ VALLEY NATIONAL HERITAGE AREA

Feasibility Study for the SANTA CRUZ VALLEY NATIONAL HERITAGE AREA FINAL Prepared by the Center for Desert Archaeology April 2005 CREDITS Assembled and edited by: Jonathan Mabry, Center for Desert Archaeology Contributions by (in alphabetical order): Linnea Caproni, Preservation Studies Program, University of Arizona William Doelle, Center for Desert Archaeology Anne Goldberg, Department of Anthropology, University of Arizona Andrew Gorski, Preservation Studies Program, University of Arizona Kendall Kroesen, Tucson Audubon Society Larry Marshall, Environmental Education Exchange Linda Mayro, Pima County Cultural Resources Office Bill Robinson, Center for Desert Archaeology Carl Russell, CBV Group J. Homer Thiel, Desert Archaeology, Inc. Photographs contributed by: Adriel Heisey Bob Sharp Gordon Simmons Tucson Citizen Newspaper Tumacácori National Historical Park Maps created by: Catherine Gilman, Desert Archaeology, Inc. Brett Hill, Center for Desert Archaeology James Holmlund, Western Mapping Company Resource information provided by: Arizona Game and Fish Department Center for Desert Archaeology Metropolitan Tucson Convention and Visitors Bureau Pima County Staff Pimería Alta Historical Society Preservation Studies Program, University of Arizona Sky Island Alliance Sonoran Desert Network The Arizona Nature Conservancy Tucson Audubon Society Water Resources Research Center, University of Arizona PREFACE The proposed Santa Cruz Valley National Heritage Area is a big land filled with small details. One’s first impression may be of size and distance—broad valleys rimmed by mountain ranges, with a huge sky arching over all. However, a closer look reveals that, beneath the broad brush strokes, this is a land of astonishing variety. For example, it is comprised of several kinds of desert, year-round flowing streams, and sky island mountain ranges. -

STREAMS in the DESERT Summary of Theme Some 90 Miles Of

Interpretive Themes and Related Resources 89 STREAMS IN THE DESERT Summary of Theme Some 90 miles of streams and rivers flow year-round in the Santa Cruz watershed. These support riparian habitats that are both beautiful and the keys to life in the desert. The word “riparian” describes the banks of streams and rivers, and the distinct plants and animals found there. At lower elevations, riparian habitats are dominated by big, billowing willow and cottonwood trees. At higher elevations, these are joined by hackberry, sycamore, ash, walnut, alder, and other trees. In dry regions such as southern Arizona, certain plants are found only in the moist conditions along streams and rivers. Some animals that roam mountains and deserts depend on visits to riparian areas, where they can rest, drink, and sometimes hunt. Other animals spend their entire lives in riparian areas and cannot survive without them. These include many fish, frogs, and bird species. Some 60-75 percent of all wildlife species in this region depend on riparian areas at some point in their lives, and 90 percent of all bird species are found in these desert oases. Riparian areas also function as movement or migration corridors for wildlife. North-south trending rivers such as the Santa Cruz are important migratory routes for birds. Description of Theme Riparian Areas Riparian communities are those ribbons of life along banks of rivers, shoreline communities along slow or non-flowing waters such as marshes and lakes, and along the banks of dry washes in deserts. Riparian communities have three components: water availability, vegetation, and wildlife.