Tucson Audubon Comments Regarding Proposed Western

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CENTRAL ARIZONA SALINITY STUDY --- PHASE I Technical Appendix C HYDROLOGIC REPORT on the PHOENIX

CENTRAL ARIZONA SALINITY STUDY --- PHASE I Technical Appendix C HYDROLOGIC REPORT ON THE PHOENIX AMA Prepared for: United States Department of Interior Bureau of Reclamation Prepared by: Brown and Caldwell 201 East Washington Street, Suite 500 Phoenix, Arizona 85004 Brown and Caldwell Project No. 23481.001 C-1 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................................ 2 LIST OF TABLES .......................................................................................................................... 3 LIST OF FIGURES ........................................................................................................................ 3 1.0 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 4 2.0 PHYSICAL SETTING ....................................................................................................... 5 3.0 GENERALIZED GEOLOGY ............................................................................................ 6 3.1 BEDROCK GEOLOGY ......................................................................................... 6 3.2 BASIN GEOLOGY ................................................................................................ 6 4.0 HYDROGEOLOGIC CONDITIONS ................................................................................ 9 4.1 GROUNDWATER OCCURRENCE .................................................................... -

Hassayampa Landscape Restoration EA Aquatics Resources Report

Hassayampa Landscape Restoration Environmental Assessment Aquatics Resources Report Prepared by: Albert Sillas Fishery Biologist Prescott National Forest for: Bradshaw Ranger District Prescott National Forest August 25, 2017 In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. Additionally, program information may be made available in languages other than English. To file a program discrimination complaint, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, AD-3027, found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html and at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to USDA and provide in the letter all of the information requested in the form. To request a copy of the complaint form, call (866) 632-9992. Submit your completed form or letter to USDA by: (1) mail: U.S. -

Soil Survey Ik Salt River Valley, Arizona

Soil Survey in Salt River Valley Item Type text; Book Authors Means, Thos. H. Publisher College of Agriculture, University of Arizona (Tucson, AZ) Rights Public Domain: This material has been identified as being free of known restrictions under U.S. copyright law, including all related and neighboring rights. Download date 28/09/2021 11:06:51 Item License http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/mark/1.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/192405 U S DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE, DIVISION OF SOILS MILTON "WHITNEY, Chief SOIL SURVEY IK SALT RIVER VALLEY, ARIZONA. THOMAS H MEANS [REPRINTED *ROM THE EFFORT o\ FIIID OPLK\.HO\S os mt I)IM^ION ot i OK 1900 ] CONTENTS. Page. Introduction _ to 287 Geology and topography _ 288 Climate 291 Soils 293 Pecos sand 294 River wash 293 Salt Eiver gravel 293 G-ilafine sandy loam 296 Salt River adobe 296 G-lendale loess „__ 299 Colluvial soils, or mountain waste - 302 Maricopa gravelly loam 303 Maricopa sandy loam _ 304 Maricopaloam 306 Maricopa clay lo?-m „ 307 Hardpan _ 308 Solrnaps - - 308 Tempesheet , 308 Phoenix sheet 309 Buckeye sheet 309 Irrigation waters 310 Underground waters 31S Tempesheet „ , 314 Phoenix sheet 315 Buckeye sheet , 317 Alkali of the soils 319 Templesheet 319 Origin of alkali salts of Tempe sheet 321 Reclamation of alkali lands 323 Phoenix &heet - - 325 Buckeye sheet-, S38 Agriculture in Salt River Valley 331 Fruit farming 331 Cattle raising - 33S Dairying * — - %8& in ILLUSTRATIONS. PLATES. PLATE XXIV. Character of native vegetation on desert land near the moun- tains 290 XXY. Irrigated lands in Tempe area 302 XXVI. -

Gila Topminnow Revised Recovery Plan December 1998

GILA TOPMINNOW, Poeciliopsis occidentalis occidentalis, REVISED RECOVERY PLAN (Original Approval: March 15, 1984) Prepared by David A. Weedman Arizona Game and Fish Department Phoenix, Arizona for Region 2 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Albuquerque, New Mexico December 1998 Approved: Regional Director, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Date: Gila Topminnow Revised Recovery Plan December 1998 DISCLAIMER Recovery plans delineate reasonable actions required to recover and protect the species. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) prepares the plans, sometimes with the assistance of recovery teams, contractors, State and Federal Agencies, and others. Objectives are attained and any necessary funds made available subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved, as well as the need to address other priorities. Time and costs provided for individual tasks are estimates only, and not to be taken as actual or budgeted expenditures. Recovery plans do not necessarily represent the views nor official positions or approval of any persons or agencies involved in the plan formulation, other than the Service. They represent the official position of the Service only after they have been signed by the Regional Director or Director as approved. Approved recovery plans are subject to modification as dictated by new findings, changes in species status, and the completion of recovery tasks. ii Gila Topminnow Revised Recovery Plan December 1998 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Original preparation of the revised Gila topminnow Recovery Plan (1994) was done by Francisco J. Abarca 1, Brian E. Bagley, Dean A. Hendrickson 1 and Jeffrey R. Simms 1. That document was modified to this current version and the work conducted by those individuals is greatly appreciated and now acknowledged. -

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 07/01/2019 to 09/30/2019 Prescott National Forest This Report Contains the Best Available Information at the Time of Publication

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 07/01/2019 to 09/30/2019 Prescott National Forest This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact R3 - Southwestern Region, Occurring in more than one Forest (excluding Regionwide) AZ Public Service (APS) ROW - Vegetation management Completed Actual: 04/09/2019 04/2019 Heather Snow Vegetation Management with (other than forest products) 505-842-3445 Herbicides - Special use management [email protected] EA Description: FS must decide whether to allow APS to include using herbicides as a method to manage vegetation on existing *UPDATED* APS transmission ROW within five National Forests in Arizona. Web Link: http://www.fs.usda.gov/project/?project=45771 Location: UNIT - Kaibab National Forest All Units, Prescott National Forest All Units, Coconino National Forest All Units, Apache-Sitgreaves National Forests All Units, Tonto National Forest All Units. STATE - Arizona. COUNTY - Coconino, Gila, Maricopa, Navajo, Yavapai. LEGAL - Not Applicable. Arizona Public Service Company Rights of Way across the Apache-Sitgreaves, Coconino, Kaibab, Prescott, and Tonto National Forests. See map on website. Prescott College Academic - Recreation management In Progress: Expected:04/2018 05/2018 Julie Rowe Outfitter and Guide Priority Use - Special use management Scoping Start 02/02/2015 928-203-7516 (2015-2025) [email protected] CE Description: The Forest Service proposes to authorize Prescott College to conduct academic courses including new student orientation, adventure education, biology, human ecology, natural history, physical geography, field ecology, environmental conservation Web Link: http://www.fs.usda.gov/project/?project=47407 Location: UNIT - Coronado National Forest All Units, Kaibab National Forest All Units, Prescott National Forest All Units, Tonto Basin Ranger District, Coconino National Forest All Units, Apache-Sitgreaves National Forests All Units. -

Environmental Assessment

United States Department of Agriculture Supplemental Forest Service Southwestern Environmental Region April 2020 Assessment Proposed Riverbend Placer Mine and Lost Nugget Reclamation Project Bradshaw Ranger District Prescott National Forest In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. Additionally, program information may be made available in languages other than English. To file a program discrimination complaint, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, AD-3027, found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html and at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to USDA and provide in the letter all of the information requested in the form. To request a copy of the complaint form, call (866) 632-9992. Submit your completed form or letter to USDA by: (1) mail: U.S. -

Native Fish Restoration in Redrock Canyon

U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Final Environmental Assessment Phoenix Area Office NATIVE FISH RESTORATION IN REDROCK CANYON U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service Southwestern Region Coronado National Forest Santa Cruz County, Arizona June 2008 Bureau of Reclamation Finding of No Significant Impact U.S. Forest Service Finding of No Significant Impact Decision Notice INTRODUCTION In accordance with the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (Public Law 91-190, as amended), the Bureau of Reclamation (Reclamation), as the lead Federal agency, and the Forest Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), and Arizona Game and Fish Department (AGFD), as cooperating agencies, have issued the attached final environmental assessment (EA) to disclose the potential environmental impacts resulting from construction of a fish barrier, removal of nonnative fishes with the piscicide antimycin A and/or rotenone, and restoration of native fishes and amphibians in Redrock Canyon on the Coronado National Forest (CNF). The Proposed Action is intended to improve the recovery status of federally listed fish and amphibians (Gila chub, Gila topminnow, Chiricahua leopard frog, and Sonora tiger salamander) and maintain a healthy native fishery in Redrock Canyon consistent with the CNF Plan and ongoing Endangered Species Act (ESA), Section 7(a)(2), consultation between Reclamation and the FWS. BACKGROUND The Proposed Action is part of a larger program being implemented by Reclamation to construct a series of fish barriers within the Gila River Basin to prevent the invasion of nonnative fishes into high-priority streams occupied by imperiled native fishes. This program is mandated by a FWS biological opinion on impacts of Central Arizona Project (CAP) water transfers to the Gila River Basin (FWS 2008a). -

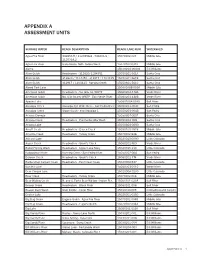

Appendix a Assessment Units

APPENDIX A ASSESSMENT UNITS SURFACE WATER REACH DESCRIPTION REACH/LAKE NUM WATERSHED Agua Fria River 341853.9 / 1120358.6 - 341804.8 / 15070102-023 Middle Gila 1120319.2 Agua Fria River State Route 169 - Yarber Wash 15070102-031B Middle Gila Alamo 15030204-0040A Bill Williams Alum Gulch Headwaters - 312820/1104351 15050301-561A Santa Cruz Alum Gulch 312820 / 1104351 - 312917 / 1104425 15050301-561B Santa Cruz Alum Gulch 312917 / 1104425 - Sonoita Creek 15050301-561C Santa Cruz Alvord Park Lake 15060106B-0050 Middle Gila American Gulch Headwaters - No. Gila Co. WWTP 15060203-448A Verde River American Gulch No. Gila County WWTP - East Verde River 15060203-448B Verde River Apache Lake 15060106A-0070 Salt River Aravaipa Creek Aravaipa Cyn Wilderness - San Pedro River 15050203-004C San Pedro Aravaipa Creek Stowe Gulch - end Aravaipa C 15050203-004B San Pedro Arivaca Cienega 15050304-0001 Santa Cruz Arivaca Creek Headwaters - Puertocito/Alta Wash 15050304-008 Santa Cruz Arivaca Lake 15050304-0080 Santa Cruz Arnett Creek Headwaters - Queen Creek 15050100-1818 Middle Gila Arrastra Creek Headwaters - Turkey Creek 15070102-848 Middle Gila Ashurst Lake 15020015-0090 Little Colorado Aspen Creek Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-769 Verde River Babbit Spring Wash Headwaters - Upper Lake Mary 15020015-210 Little Colorado Babocomari River Banning Creek - San Pedro River 15050202-004 San Pedro Bannon Creek Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-774 Verde River Barbershop Canyon Creek Headwaters - East Clear Creek 15020008-537 Little Colorado Bartlett Lake 15060203-0110 Verde River Bear Canyon Lake 15020008-0130 Little Colorado Bear Creek Headwaters - Turkey Creek 15070102-046 Middle Gila Bear Wallow Creek N. and S. Forks Bear Wallow - Indian Res. -

Water Resource Planning Sustainable Cities Network November 7, 2019 Organizational Structure Secretary of the Interior David Bernhardt

Water Resource Planning Sustainable Cities Network November 7, 2019 Organizational Structure Secretary of the Interior David Bernhardt Asst. Secretary Asst. Secretary of Water & of Asst. Secretary Science Fish, Wildlife & of Indian Affairs Asst. Secretary Parks of Land & Bureau of Minerals National Park Service Indian Affairs Bureau of Bureau of Reclamation Land Management Commissioner Brenda Burman U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Office of Surfacing Mining U.S. Geological Reclamation & Enforcement Survey 2 Lower Colorado Region Utah New Mexico Arizona 3 Phoenix Area Office Boundaries COLORADO RIVER VERDE RIVER SALT RIVER GILA RIVER SAN PEDRO RIVER Mission The mission of the Bureau of Reclamation is to manage, develop, and protect water and related resources in an environmentally and economically sound manner in the interest of the American public. Overview • Largest water provider in the 17 western States (479 dams and 348 reservoirs) • Nation’s second largest producer of hydroelectric power • Develops authorized facilities to store and convey new water supplies Recharge Xeriscape Water Treatment Wetlands Irrigation Efficiencies 7 Drought Contingency Plan (DCP) • Consensus-based drought contingency plans were developed • each basin state • American Indian tribes • Mexico • DCP includes • Basin state voluntary reductions and other actions • Mexico agreed to implement a Binational Water Scarcity Contingency Plan after the United States adopted the DCP Colorado River Basin Overview • 16.5 million acre-feet (maf) allocated annually - 7.5 maf -

Flood Insurance Study Vol. 1

SANTA CRUZ COUNTY, ARIZONA AND INCORPORATED AREAS VOLUME 1 OF 3 Community Community Name Number SANTA CRUZ COUNTY, (UNINCORPORATED AREAS) 040090 NOGALES, CITY OF 040091 PATAGONIA, TOWN OF 040092 Santa Cruz County EFFECTIVE: DECEMBER 2, 2011 Federal Emergency Management Agency FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY NUMBER 04023CV001A NOTICE TO FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY USERS Communities participating in the National Flood Insurance Program have established repositories of flood hazard data for floodplain management and flood insurance purposes. This Flood Insurance Study (FIS) may not contain all data available within the repository. Please contact the Community Map Repository for any additional data. Part or all of this FIS may be revised and republished at any time. In addition, part of this FIS report may be revised by the Letter of Map Revision process, which does not involve republication or redistribution of the FIS report. It is, therefore, the responsibility of the user to consult with community officials and to check the community repository to obtain the most current FIS report components. Selected Flood Insurance Rate Map (FIRM) panels for this community contain information that was previously shown separately on the corresponding Flood Boundary and Floodway Map (FBFM) panels (e.g., floodways, cross sections). In addition, former flood hazard zone designations have been changed as follows: Old Zone(s) New Zone A1 through A30 AE B X C X Initial Countywide FIS Report Effective Date: December 2, 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS – VOLUME 1 Page 1.0 INTRODUCTION -

Proquest Dissertations

An ethnographic perspective on prehistoric platform mounds of the Tonto Basin, Central Arizona Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Elson, Mark David, 1955- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 10/10/2021 00:20:59 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/290644 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfihn master. UMI fihns the text directly from the orighud or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter fiice, \^e others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, b^inning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. -

Feasibility Study for the SANTA CRUZ VALLEY NATIONAL HERITAGE AREA

Feasibility Study for the SANTA CRUZ VALLEY NATIONAL HERITAGE AREA FINAL Prepared by the Center for Desert Archaeology April 2005 CREDITS Assembled and edited by: Jonathan Mabry, Center for Desert Archaeology Contributions by (in alphabetical order): Linnea Caproni, Preservation Studies Program, University of Arizona William Doelle, Center for Desert Archaeology Anne Goldberg, Department of Anthropology, University of Arizona Andrew Gorski, Preservation Studies Program, University of Arizona Kendall Kroesen, Tucson Audubon Society Larry Marshall, Environmental Education Exchange Linda Mayro, Pima County Cultural Resources Office Bill Robinson, Center for Desert Archaeology Carl Russell, CBV Group J. Homer Thiel, Desert Archaeology, Inc. Photographs contributed by: Adriel Heisey Bob Sharp Gordon Simmons Tucson Citizen Newspaper Tumacácori National Historical Park Maps created by: Catherine Gilman, Desert Archaeology, Inc. Brett Hill, Center for Desert Archaeology James Holmlund, Western Mapping Company Resource information provided by: Arizona Game and Fish Department Center for Desert Archaeology Metropolitan Tucson Convention and Visitors Bureau Pima County Staff Pimería Alta Historical Society Preservation Studies Program, University of Arizona Sky Island Alliance Sonoran Desert Network The Arizona Nature Conservancy Tucson Audubon Society Water Resources Research Center, University of Arizona PREFACE The proposed Santa Cruz Valley National Heritage Area is a big land filled with small details. One’s first impression may be of size and distance—broad valleys rimmed by mountain ranges, with a huge sky arching over all. However, a closer look reveals that, beneath the broad brush strokes, this is a land of astonishing variety. For example, it is comprised of several kinds of desert, year-round flowing streams, and sky island mountain ranges.