Impacts of Underwater Photography on Cryptobenthic Fauna Found in Soft Sediment Habitats

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Underwater Photography Made Easy

Underwater Photography Made Easy Create amazing photos & video with by Annie Crawley IncludingIncluding highhigh definitiondefinition videovideo andand photophoto galleriesgalleries toto showshow youyou positioningpositioning andand bestbest techniques!techniques! BY ANNIE CRAWLEY SeaLife Cameras Perfect for every environment whether you are headed on a tropical vacation or diving the Puget Sound. These cameras meet all of your imaging needs! ©2013 Annie Crawley www.Sealife-cameras.com www.DiveIntoYourImagination.com Edmonds Underwater Park, Washington All rights reserved. This interactive book, or parts thereof, may not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher, Dive Into Your Imagination, LLC a company founded by Annie Crawley committed to change the way a new generation views the Ocean and themselves. Dive Into Your Imagination, Reg. Pat. & Tm. Off. Underwater Photography Made Easy shows you how to take great photos and video with your SeaLife camera system. After our introduction to this interactive book you will learn: 1. Easy to apply tips and tricks to help you create great images. 2. Five quick review steps to make sure your SeaLife camera system is ready before every dive. 3. Neutral buoyancy tips to help you take great underwater photos & video with your SeaLife camera system. 4. Macro and wide angle photography and video basics including color, composition, understanding the rule of thirds, leading diagonals, foreground and background considerations, plus lighting with strobes and video lights. 5. Techniques for both temperate and tropical waters, how to photograph divers, fish behavior and interaction shots, the difference in capturing animal portraits versus recording action in video. You will learn how to capture sharks, turtles, dolphins, clownfish, plus so much more. -

Underwater Photographyphotography a Web Magazine

UnderwaterUnderwater PhotographyPhotography a web magazine Oct/Nov 2002 Nikon D100 housings Fuji S2 housing Sony F707 housing Kodak DCS Pro 14n Sperm whale Nai’a liveaboard U/w photojournalist - Jack Jackson Henry the seadragon Scilly Seals Lights & divers Easy macro British fish Underwater tripod Visions 2002 UwP 1 What links these sites? Turn to page 7 to find out... UwP 2 UnderwaterUnderwater PhotographyPhotography a web magazine Oct/Nov 2002 e mail [email protected] Contents 4 Travel & events 30 Meet Henry 43 Easy macro 8 New products 14 Sperm whale by Andy & Angela Heath with Ee wan Khoo 35 Scilly Seals 47 British fish with Tony Wu 19 Nai’a liveaboard with Will & Demelza by Mark Webster Posslethwaite 54 Size matters 35 Lights & divers by Jukka Nurminen & Alex Mustard by Pete Atkinson 25 U/w photojournalist by Martin Edge Cover photo by Tony Wu 58 Visions 2002 by Jack Jackson UwP 3 Travel & events Jim Breakell Tahiti talk at Dive Show, Oct 12/13 2002 In September Jim Breakell of Scuba Safaris went on a fact finding trip to the Pacific. First off he went to Ryrutu for for a few days humpback whale watching, then a week on the inaugural trip of the Tahiti Aggressor and then on to Bora Bora (what a hard life he has!) He will be giving an illustrated talk about his trip at the Dive Show in Birmingham on October 12/13th 2002. For more information contact Scuba Safaris, PO Box 8, Edenbridge, Kent TN8 7ZS. Tel 01342 851196. www.scuba-safaris.com John Boyle video trip May 2003 INVITATION John Boyle will be hosting a video diving trip from Bali to Komodo on Kararu next year. -

Summer/Autumn | 2019

Summer/Autumn | 2019 Philippines DIVE ADVENTURE What’s Bubbling ALL NEW Island of the Gods BALI Bula from FIJI Dive in SMALL GROUP TRIPS Philippines Dive Adventure Threshers, rays & critters Earlier this year, client Sara Jenner asked us to design a trip to the Philippines combining rest, relaxation and diving. In this article she describes her adventure to Malapascua and Bohol in search of thresher sharks, critters and pelagics. fter much discussion with my Travel five-minute walk to the dive centre. The with small critters and nudibranchs. Consultant (Cath), I decided on a hotel offered everything I needed plus A twin-centre holiday in the plenty of personal touches. And I can Next stop was Bohol. I stayed at Alona Philippines. I was looking for some highly recommend the ‘overnight oats’ Vida Beach Resort, which is relatively quiet much-needed rest and relaxation in the with frozen banana from the breakfast considering its central location, and the sun, with a good mix of diving (so I could buffet to set you up for the day. dive centre is situated in a lovely peaceful play with my new underwater camera) … Malapascua is famous for its pelagic site. There were plenty of great dives just a most importantly, at an affordable price, thresher sharks, and I made the necessary few hundred metres off the main beach, and the Philippines seemed to tick all these early start to see them three times during with beautiful coral-covered walls teeming boxes. my week-long stay! The diversity of macro with macro life. For bigger pelagic species life was astonishing and makes this an it’s worth heading out to Balicasag Island I started my adventure in Malapascua, ideal place for any keen photographer. -

Dive Log Australia

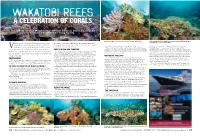

WAKATOBI REEFS A CELEBRATION OF CORALS The famous resort of Wakatobi in South East Sulawesi, Indonesia, probably needs no introduction for many readers. The shallow reef flats in 1 or 2 meters are a great place to start Blue waters swirl above and a hint of clouds in a blue sky prevail. Early morning shafts of sunlight bathe a coral head with light producing a surreal image of corals in the sunlight. eteran pioneer Australian Underwater Photographer the idyllic location and accommodation, the wonderful hospitality, Kevin Deacon decided to forgo all other genres of the range of dive sites, dive boat facilities and all round diver support, one will not suffer for their art here! clown fish and fast growing Acropora & soft corals. produced a portfolio that I believe is faithful to the genre of Vunderwater photography during his most recent tour While cruising this area the creative mind must be fully engaged "Beautiful Reefs". I hope you enjoy these images and the to concentrate on capturing the simple beauty of Wakatobi REEF HUNTING AND SHOOTING looking for the right coral reef elements. By its very nature coral reefs information here helps you on your way as a `Master of the Light’. Indo Pacific coral reefs. A task not as simple as it might seem Creating such images comes with some great challenges. Cruising and their inhabitants are designed to create confusion to the eye, all Kevin Deacon is one of the pioneers of underwater photography in but the resulting images illustrate the value in the age old rule, a coral reef leaves one with an impression of living beauty with part of nature's survival strategy. -

Diving Differences Between Puerto Galera and Dumaguete

If you are wondering what’s the difference in diving between Puerto Galera and Dumaguete, dive both! If you only have time for one you may consider the following differences: ● Dive sites- both locations offer house reefs, and day trips. ○ Puerto Galera diving is mostly colorful reefs with very diverse topography, such as walls, ledges, big coral heads and even a proper wreck (Alma Jane). There are a couple of sites for muck diving, and quite a few sites that are only suitable for advanced divers (Canyons, Kilima Drift). ○ Dumaguete dive sites offer a combination of sloping reef and sandy areas; muck diving fanatics are in heaven here as our coastal diving is like muck diving but with 40’ + visibility, a black sand bottom instead of silt, no trash yet with all the same critters found in the muck. There are also several artificial reef sites in Dumaguete (House Reef, Cars, Sahara, Ginamaan), and all sites are diveable for beginners. ● Day trips out of Puerto Galera include Verde Island, while from Dumaguete you can dive Apo Island, Siquijor and snorkel with the whale sharks in Oslob ● Current- Puerto Galera typically has more current than Dumaguete. ● Aquatic Life ○ Puerto Galera - you’re more likely to spot pelagics here because of stronger currents, plus, there are more nudibranchs (over 180 species) than Dumaguete. Compared to Anilao, Puerto Galera offers greater fish and coral variety. ○ Dumaguete- offers a higher diversity of coastal diving critters, and the fish are less shy because of the Marine protected Areas. Diving in Apo Island (a day trip from Dumaguete) offers the colorful corals, many turtles and a chance of seeing pelagics such as sharks and rays. -

Underwater Survey for Oil and Gas Industry: a Review of Close Range Optical Methods

remote sensing Review Underwater Survey for Oil and Gas Industry: A Review of Close Range Optical Methods Bertrand Chemisky 1,*, Fabio Menna 2 , Erica Nocerino 1 and Pierre Drap 1 1 LIS UMR 7020, Aix-Marseille Université, CNRS, Université De Toulon, 13397 Marseille, France; [email protected] (E.N.); [email protected] (P.D.) 2 3D Optical Metrology (3DOM) Unit, Bruno Kessler Foundation (FBK), Via Sommarive 18, 38123 Trento, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: In both the industrial and scientific fields, the need for very high-resolution cartographic data is constantly increasing. With the aging of offshore subsea assets, it is very important to plan and maintain the longevity of structures, equipment, and systems. Inspection, maintenance, and repair (IMR) of subsea structures are key components of an overall integrity management system that aims to reduce the risk of failure and extend the life of installations. The acquisition of very detailed data during the inspection phase is a technological challenge, especially since offshore installations are sometimes deployed in extreme conditions (e.g., depth, hydrodynamics, visibility). After a review of high resolution mapping techniques for underwater environment, this article will focus on optical sensors that can satisfy the requirements of the offshore industry by assessing their relevance and degree of maturity. These requirements concern the resolution and accuracy but also cost, ease of implementation, and qualification. With the evolution of embedded computing resources, in-vehicle optical survey solutions are becoming increasingly important in the landscape of large-scale mapping solutions and more and more off-the-shelf systems are now available. -

East Flores Witness Something Truly Majestic®

East Flores Witness Something Truly Majestic® thth 8SAFARI Page 1 The Mystical Archipelago of Lembata & Alor Venture to the isolated archipelago where its myth, culture and wilderness are lost in time. Legend has it that after a particularly long drought in the Dolabang Village at Pura Island, a local man, Olangki, made a journey to Reta Village to borrow rice. The following year, while on way to return the borrowed rice, he saw a pig on the top of Maru Mountain. He tried, but failed, to slay the pig. In his despair, he asked for help from Dewa “God” to give him water and in return he would give away his daughter, “Bui”. The sky turned dark and with it came a big rain which flooded the village. After he gave his daughter to the God, the rain stopped. After a year, the villagers had enough food and water to live on. They celebrated their good fortune with the Lego-Lego Dance and invited Bui to join them. Bui was believed to be married to the God of the mountain. While dancing, Bui asked her mother to take care of her baby that was wrapped in a blanket. She told her mother not to open the blanket. Despite her request, the mother opened the blanket and found a big red fish. She could not resist eating one of the eyes. When Bui discovered that the mother had hurt her baby, she ran and locked herself inside Bitu Era cave at the top of the mountain. She promised herself that there would be no more hunger and thirst for her family and village. -

Underwater Optical Imaging: Status and Prospects

Underwater Optical Imaging: Status and Prospects Jules S. Jaffe, Kad D. Moore Scripps Institution of Oceanography. La Jolla, California USA John McLean Arete Associates • Tucson, Arizona USA Michael R Strand Naval Surface Warfare Center. Panama City, Florida USA Introduction As any backyard stargazer knows, one simply has vision, and photography". Subsequent to that, there to look up at the sky on a cloudless night to see light have been several books which have summarized a whose origin was quite a long time ago. Here, due to technical understanding of underwater imaging such as the fact that the mean scattering and absorption Merten's book entitled "In Water Photography" lengths are greater in size than the observable uni- (Mertens, 1970) and a monograph edited by Ferris verse, one can record light from stars whose origin Smith (Smith, 1984). An interesting conference which occurred around the time of the big bang. took place in 1970 resulted in the publication of several Unfortunately for oceanographers, the opacity of sea papers on optics of the sea, including the air water inter- water to light far exceeds these intergalactic limits, face and the in water transmission and imaging of making the job of collecting optical images in the ocean objects (Agard, 1973). In this decade, several books by a difficult task. Russian authors have appeared which treat these prob- Although recent advances in optical imaging tech- lems either in the context of underwater vision theory nology have permitted researchers working in this area (Dolin and Levin, 1991) or imaging through scattering to accomplish projects which could only be dreamed of media (Zege et al., 1991). -

Imaging the Twilight Zone: the Morphology And

IMAGING THE TWILIGHT ZONE: THE MORPHOLOGY AND DISTRIBUTION OF MESOPHOTIC ZONE FEATURES, A CASE STUDY FROM BONAIRE, DUTCH CARIBBEAN by Bryan Mark Keller A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Marine Studies Spring 2011 Copyright 2011 Bryan M. Keller All Rights Reserved IMAGING THE TWILIGHT ZONE: THE MORPHOLOGY AND DISTRIBUTION OF MESOPHOTIC ZONE FEATURES, A CASE STUDY FROM BONAIRE, DUTCH CARIBBEAN by Bryan Mark Keller Approved: _____________________________________________________ Arthur C. Trembanis, Ph.D. Professor in charge of thesis on behalf of the Advisory Committee Approved: _____________________________________________________ Charles E. Epifanio, Ph.D. Director of the School of Marine Science and Policy Approved: _____________________________________________________ Nancy M. Targett, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Earth, Ocean, and Environment Approved: _____________________________________________________ Charles G. Riordan, Ph.D. Vice Provost for Graduate and Professional Education ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Art Trembanis, for his instruction and support throughout my thesis research. My gratitude is also extended to Dr. Douglas Miller and Dr. Mark Patterson for their assistance and guidance throughout the entirety of my research. Much thanks to the University of Delaware Office of Graduate and Professional Education, the Department of Oceanography, and the Department of Geology for the funding necessary for me to perform m fieldwork in Bonaire. Finally, I would like to thank my lab mates and colleagues for answering my countless questions and always being willing to provide insight about any problems that I faced. iii DEDICATION This manuscript is dedicated to Rachel Lyons who has known me through all of my struggles and always insisted that I chase my dreams. -

Chapter 6 Underwater Photography

Chapter 6 Underwater Photography It is hard to imagine a more difficult endeavor than taking pictures underwater. You have to be at least partially crazy to get involved in it, and if you are not crazy when you start, it is virtually guaranteed to make you crazy. First, you have to learn to survive in an alien environment. Before you even think about the highly specialized photographic equipment required, you have to learn how to safely breathe and move about underwater. That means you have to become a certified diver. The most important qualification required to become a good underwater photographer is to be a good diver. You can’t worry about things like f- stops, depth of field, shutter speeds, exposure, point of focus, and other technical photographic stuff if you are not comfortable underwater. Things like breath and buoyancy control, awareness of time, depth and tank air pressure, must become second nature, like shifting while driving a car with a manual transmission. Underwater photography, even with excellent diving skills, state-of-the-art equipment, and plentiful subjects, is still a very low batting average endeavor. You fail much more often than you succeed. That means that you discard a lot more images than you keep. But the occasional “keeper” can make up for all the throwaways. Underwater photography offers the highest highs, and the lowest lows of any endeavor I know. Everything in underwater photography is stacked against success. First, unlike taking pictures topside, you have a very limited amount of time to capture your image (before you have to surface or drown.) Whatever underwater subject you are seeking on each dive, you have to find it in less than an hour, you can’t hang around all day waiting for something to appear. -

For Memorable Underwater Photography Thank You for Downloading Our Guide “10 Professional Tips for Memorable Underwater Photography”

10 Professional TIPS for Memorable Underwater Photography Thank you for downloading our guide “10 Professional Tips for Memorable Underwater Photography”. Taking images and videos of beautiful marine life is so very exciting and we are thrilled for you to join the spectacular world of marine photography! Welcome!! Within these pages, you will find tips and helpful suggestions on how to prepare your underwater camera and yourself! Think of it as your guide to everything you need to know to say SAFE and share awesome underwater video and pictures with the world. The information gathered is backed up by our combined 45+ years of field experience of diving, snorkeling, guiding, observing, researching and FILMING the Kona Manta Rays. We hope you enjoy the guide and please consider helping us by sharing it on social media. Let’s dive in…. Warmest Aloha JAMES L. WING MARTINA L. WING Today, you have so many choices when it comes to compact, easy to use underwater cameras. We Tips for see people using GoPro’s, disposable cameras or even IPhones. Underwater Here is the trick though. As much as we want Video and to encourage you to keep a memory of the underwater world, you are operating often in a Pictures low-light environment with fast moving creatures. What your eyes see is not necessarily what your camera captures. BE CONFORTABLE WITH YOUR SNORKEL OR 1TIP DIVE EQUIPMENT SAFETY FIRST! You are leaving the humans’ comfort zone, the place of constant air supply, and you are entering an environment that requires multi- tasking. We recommend mastering your ocean skills and gear before you add the additional task of taking pictures in the ocean with beautiful fish in front of you! WWW.MANTARAYADVOCATES.COM 2 The extra complex task of photography usually results in mediocre imagery and unsafe practices. -

5 Top Tips for Underwater Photography

5 Top Tips for Underwater Photography PUBLISHED - 31 JUL 2016 Make waves with your photography this summer by going underneath them with your camera… 1) Play it safe COOLPIX AW130 First and foremost, never swim, snorkel or Scuba dive beyond your abilities. Second, keep your kit safe, too. While most cameras won't thank you for taking a dip with them, Nikon has several waterproof COOLPIX models, including the AW130 (waterproof down to 30m – the same as an advanced open-water diving qualification) and W100 (waterproof to 10m), while the Nikon 1 AW1 is waterproof to 15m. You can also buy waterproof cases for Nikon 1 cameras, enabling them to dive with you down to an impressive 45m – about the depth of the Straits of Dover! If you're very keen, invest in a bespoke underwater casing for your DSLR – expensive but worth every penny if this is an area you really want to get into. 2) Use underwater mode. 1 of 4 The deeper underwater you go, the less colourful things appear, as the coloured wavelengths of light are gradually filtered out: red disappears first at around 5m, followed by orange (10m), yellow (20m), green (30m) and blue at 60m. What this means is that, without correcting for it, whatever you shoot will tend to look greeny-blue. Unless you're shooting extremely close up, don't try to combat this with on-camera flash, as that will light up the myriad tiny floating particles in the water (believe us, they're there, and even if your eyes don't see them, your camera will).