Croatia Page 1 of 24

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FEEFHS Journal Volume VII No. 1-2 1999

FEEFHS Quarterly A Journal of Central & Bast European Genealogical Studies FEEFHS Quarterly Volume 7, nos. 1-2 FEEFHS Quarterly Who, What and Why is FEEFHS? Tue Federation of East European Family History Societies Editor: Thomas K. Ecllund. [email protected] (FEEFHS) was founded in June 1992 by a small dedicated group Managing Editor: Joseph B. Everett. [email protected] of American and Canadian genealogists with diverse ethnic, reli- Contributing Editors: Shon Edwards gious, and national backgrounds. By the end of that year, eleven Daniel Schlyter societies bad accepted its concept as founding members. Each year Emily Schulz since then FEEFHS has doubled in size. FEEFHS nows represents nearly two hundred organizations as members from twenty-four FEEFHS Executive Council: states, five Canadian provinces, and fourteen countries. lt contin- 1998-1999 FEEFHS officers: ues to grow. President: John D. Movius, c/o FEEFHS (address listed below). About half of these are genealogy societies, others are multi-pur- [email protected] pose societies, surname associations, book or periodical publish- 1st Vice-president: Duncan Gardiner, C.G., 12961 Lake Ave., ers, archives, libraries, family history centers, on-line services, in- Lakewood, OH 44107-1533. [email protected] stitutions, e-mail genealogy list-servers, heraldry societies, and 2nd Vice-president: Laura Hanowski, c/o Saskatchewan Genealogi- other ethnic, religious, and national groups. FEEFHS includes or- cal Society, P.0. Box 1894, Regina, SK, Canada S4P 3EI ganizations representing all East or Central European groups that [email protected] have existing genealogy societies in North America and a growing 3rd Vice-president: Blanche Krbechek, 2041 Orkla Drive, group of worldwide organizations and individual members, from Minneapolis, MN 55427-3429. -

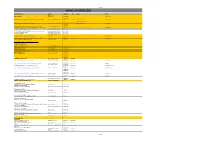

Grad Zagreb (01)

ADRESARI GRAD ZAGREB (01) NAZIV INSTITUCIJE ADRESA TELEFON FAX E-MAIL WWW Trg S. Radića 1 POGLAVARSTVO 10 000 Zagreb 01 611 1111 www.zagreb.hr 01 610 1111 GRADSKI URED ZA STRATEGIJSKO PLANIRANJE I RAZVOJ GRADA Zagreb, Trg Stjepana Radića 1/II 01 610 1575 610-1292 [email protected] www.zagreb.hr [email protected] 01 658 5555 01 658 5609 GRADSKI URED ZA POLJOPRIVREDU I ŠUMARSTVO Zagreb, Avenija Dubrovnik 12/IV 01 658 5600 [email protected] www.zagreb.hr 01 610 1111 01 610 1169 GRADSKI URED ZA PROSTORNO UREĐENJE, ZAŠTITU OKOLIŠA, Zagreb, Trg Stjepana Radića 1/I 01 610 1168 IZGRADNJU GRADA, GRADITELJSTVO, KOMUNALNE POSLOVE I PROMET 01 610 1560 01 610 1173 [email protected] www.zagreb.hr 1.ODJEL KOMUNALNOG REDARSTVA Zagreb, Trg Stjepana Radića 1/I 01 61 06 111 2.DEŽURNI KOMUNALNI REDAR (svaki dan i vikendom od 08,00-20,00 sati) Zagreb, Trg Stjepana Radića 1/I 01 61 01 566 3. ODJEL ZA UREĐENJE GRADA Zagreb, Trg Stjepana Radića 1/I 01 61 01 184 4. ODJEL ZA PROMET Zagreb, Trg Stjepana Radića 1/I 01 61 01 111 Zagreb, Ulica Republike Austrije 01 610 1850 GRADSKI ZAVOD ZA PROSTORNO UREĐENJE 18/prizemlje 01 610 1840 01 610 1881 [email protected] www.zagreb.hr 01 485 1444 GRADSKI ZAVOD ZA ZAŠTITU SPOMENIKA KULTURE I PRIRODE Zagreb, Kuševićeva 2/II 01 610 1970 01 610 1896 [email protected] www.zagreb.hr GRADSKI ZAVOD ZA JAVNO ZDRAVSTVO Zagreb, Mirogojska 16 01 469 6111 INSPEKCIJSKE SLUŽBE-PODRUČNE JEDINICE ZAGREB: 1)GRAĐEVINSKA INSPEKCIJA 2)URBANISTIČKA INSPEKCIJA 3)VODOPRAVNA INSPEKCIJA 4)INSPEKCIJA ZAŠTITE OKOLIŠA Zagreb, Trg Stjepana Radića 1/I 01 610 1111 SANITARNA INSPEKCIJA Zagreb, Šubićeva 38 01 658 5333 ŠUMARSKA INSPEKCIJA Zagreb, Zapoljska 1 01 610 0235 RUDARSKA INSPEKCIJA Zagreb, Ul Grada Vukovara 78 01 610 0223 VETERINARSKO HIGIJENSKI SERVIS Zagreb, Heinzelova 6 01 244 1363 HRVATSKE ŠUME UPRAVA ŠUMA ZAGREB Zagreb, Kosirnikova 37b 01 376 8548 01 6503 111 01 6503 154 01 6503 152 01 6503 153 01 ZAGREBAČKI HOLDING d.o.o. -

Belgrade - Budapest - Ljubljana - Zagreb Sample Prospect

NOVI SAD BEOGRAD Železnička 23a Kraljice Natalije 78 PRODAJA: PRODAJA: 021/422-324, 021/422-325 (fax) 011/3616-046 [email protected] [email protected] KOMERCIJALA: KOMERCIJALA 021/661-07-07 011/3616-047 [email protected] [email protected] FINANSIJE: [email protected] LICENCA: OTP 293/2010 od 17.02.2010. www.grandtours.rs BELGRADE - BUDAPEST - LJUBLJANA - ZAGREB SAMPLE PROSPECT 1st day – BELGRADE The group is landing in Serbia after which they get on the bus and head to the downtown Belgrade. Sightseeing of the Belgrade: National Theatre, House of National Assembly, Patriarchy of Serbian Orthodox Church etc. Upon request of the group, Tour of The Saint Sava Temple could be organized. The tour of Kalemegdan fortress, one of the biggest fortress that sits on the confluence of Danube and Sava rivers. Upon request of the group, Avala Tower visit could be organized, which offers a view of mountainous Serbia on one side and plain Serbia on the other. Departure for the hotel. Dinner. Overnight stay. 2nd day - BELGRADE - NOVI SAD – BELGRADE Breakfast. After the breakfast the group would travel to Novi Sad, consider by many as one of the most beautiful cities in Serbia. Touring the downtown's main streets (Zmaj Jovina & Danube street), Danube park, Petrovaradin Fortress. The trip would continue towards Sremski Karlovci, a beautiful historic place close to the city of Novi Sad. Great lunch/dinner option in Sremski Karlovci right next to the Danube river. After the dinner, the group would head back to the hotel in Belgrade. -

Croatia Page 1 of 24

2008 Human Rights Report: Croatia Page 1 of 24 2008 Human Rights Report: Croatia BUREAU OF DEMOCRACY, HUMAN RIGHTS, AND LABOR 2008 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices February 25, 2009 The Republic of Croatia is a constitutional parliamentary democracy with a population of 4.4 million. Legislative authority is vested in the unicameral Sabor (parliament). The president serves as head of state and commander of the armed forces, cooperating in formulation and execution of foreign policy; he also nominates the prime minister, who leads the government. Domestic and international observers stated that the November 2007 parliamentary elections were in accord with international standards. The government generally respected the human rights of its citizens; however, there were problems in some areas. The judicial system suffered from a case backlog, although courts somewhat reduced the number of unresolved cases awaiting trial. Intimidation of some witnesses in domestic war crimes trials remained a problem. The government made little progress in restituting property nationalized by the Yugoslav communist regime to non- Roman Catholic religious groups. Societal violence and discrimination against ethnic minorities, particularly Serbs and Roma, remained a problem. Violence and discrimination against women continued. Trafficking in persons, violence and discrimination against homosexuals, and discrimination against persons with HIV/AIDS were also reported. RESPECT FOR HUMAN RIGHTS Section 1 Respect for the Integrity of the Person, Including Freedom From: a. Arbitrary or Unlawful Deprivation of Life There were no reports that the government or its agents committed arbitrary or unlawful killings. During the year one mine removal expert and one civilian were killed, and one mine removal experts and two civilians were severely injured. -

From Understanding to Cooperation Promoting Interfaith Encounters to Meet Global Challenges

20TH ANNUAL EPP GROUP INTERCULTURAL DIALOGUE WITH CHURCHES AND RELIGIOUS INSTITUTIONS FROM UNDERSTANDING TO COOPERATION PROMOTING INTERFAITH ENCOUNTERS TO MEET GLOBAL CHALLENGES Zagreb, 7 - 8 December 2017 20TH ANNUAL EPP GROUP INTERCULTURAL DIALOGUE WITH CHURCHES AND RELIGIOUS INSTITUTIONS / 3 PROGRAMME 10:00-12:30 hrs / Sessions I and II The role of religion in European integration process: expectations, potentials, limits Wednesday, 6 December 10:00-11:15 hrs Session I 20.30 hrs. / Welcome Reception hosted by the Croatian Delegation / Memories and lessons learned during 20 years of Dialogue Thursday, 7 December Co-Chairs: György Hölvényi MEP and Jan Olbrycht MEP, Co-Chairmen of 09:00 hrs / Opening the Working Group on Intercultural Activities and Religious Dialogue György Hölvényi MEP and Jan Olbrycht MEP, Co-Chairmen of the Working Opening message: Group on Intercultural Activities and Religious Dialogue Dubravka Šuica MEP, Head of Croatian Delegation of the EPP Group Alojz Peterle MEP, former Responsible of the Interreligious Dialogue Welcome messages Interventions - Mairead McGuinness, First Vice-President of the European Parliament, - Gordan Jandroković, Speaker of the Croatian Parliament responsible for dialogue with religions (video message) - Joseph Daul, President of the European People’ s Party - Joseph Daul, President of the European People’ s Party - Vito Bonsignore, former Vice-Chairman of the EPP Group responsible for - Andrej Plenković, Prime Minister of Croatia Dialogue with Islam - Mons. Prof. Tadeusz Pieronek, Chairman of the International Krakow Church Conference Organizing Committee - Stephen Biller, former EPP Group Adviser responsible for Interreligious Dialogue Discussion 20TH ANNUAL EPP GROUP INTERCULTURAL DIALOGUE WITH CHURCHES AND RELIGIOUS INSTITUTIONS / 5 4 /20TH ANNUAL EPP GROUP INTERCULTURAL DIALOGUE WITH CHURCHES AND RELIGIOUS INSTITUTIONS 11:15-12:30 hrs. -

Memorial of the Republic of Croatia

INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE CASE CONCERNING THE APPLICATION OF THE CONVENTION ON THE PREVENTION AND PUNISHMENT OF THE CRIME OF GENOCIDE (CROATIA v. YUGOSLAVIA) MEMORIAL OF THE REPUBLIC OF CROATIA APPENDICES VOLUME 5 1 MARCH 2001 II III Contents Page Appendix 1 Chronology of Events, 1980-2000 1 Appendix 2 Video Tape Transcript 37 Appendix 3 Hate Speech: The Stimulation of Serbian Discontent and Eventual Incitement to Commit Genocide 45 Appendix 4 Testimonies of the Actors (Books and Memoirs) 73 4.1 Veljko Kadijević: “As I see the disintegration – An Army without a State” 4.2 Stipe Mesić: “How Yugoslavia was Brought Down” 4.3 Borisav Jović: “Last Days of the SFRY (Excerpts from a Diary)” Appendix 5a Serb Paramilitary Groups Active in Croatia (1991-95) 119 5b The “21st Volunteer Commando Task Force” of the “RSK Army” 129 Appendix 6 Prison Camps 141 Appendix 7 Damage to Cultural Monuments on Croatian Territory 163 Appendix 8 Personal Continuity, 1991-2001 363 IV APPENDIX 1 CHRONOLOGY OF EVENTS1 ABBREVIATIONS USED IN THE CHRONOLOGY BH Bosnia and Herzegovina CSCE Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe CK SKJ Centralni komitet Saveza komunista Jugoslavije (Central Committee of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia) EC European Community EU European Union FRY Federal Republic of Yugoslavia HDZ Hrvatska demokratska zajednica (Croatian Democratic Union) HV Hrvatska vojska (Croatian Army) IMF International Monetary Fund JNA Jugoslavenska narodna armija (Yugoslav People’s Army) NAM Non-Aligned Movement NATO North Atlantic Treaty Organisation -

Poland, Czech Republic, Austria, Hungary, Croatia & Medjugorje

Poland, Czech Republic, Austria, Hungary, Croatia & Medjugorje Warsaw, Krakow, Wadowice, Prague, Vienna, Budapest, Zagreb, Medjugorje Day 1 – Depart U.S.A Day 9 – Vienna - Budapest Day 2 –Arrive Warsaw This morning we drive to Budapest, the capital of Hungary. Our sightseeing tour includes the older section: Buda, located on the right bank of the Day 3 – Warsaw - Niepokalanow - Czestochowa - Krakow Danube River, where the Royal Castle, the Cathedral of St. Matthew After a panoramic tour of Warsaw, we depart to Niepokalanow, home of and Fisherman’s Bastion can be found. Enjoy views of the Neo-Gothic the Basilica of the Virgin Mary, and a Franciscan monastery founded by St. Parliament, Hero’s Square and the Basilica of St. Stephen. Maximilian Kolbe. On to Czestochowa to visit Jasna Gora Monastery and see the Black Madonna at the Gothic Chapel of Our Lady. Day 10 – Budapest - Marija Bistrica - Zagreb Depart Budapest to Zagreb. En route we stop to visit the brilliant and Day 4 – Krakow - Lagiewniki - Wieliczka spectacular sanctuary of Our Lady of Marija Bistrica, the national Shrine of Our morning tour will include visits to Wawel Hill, the Royal Chambers Croatia and home to the miraculous statue of the Virgin Mary. and Cathedral. Then walk along Kanonicza Street, where Pope John Paul II resided while living in Krakow, then to the Mariacki Church and the Market Day 11 – Zagreb - Split - Medjugorje Square. We will spend the afternoon at the Lagiewniki “Divine Mercy In the morning we depart Zagreb to Medjugorje. En route we stop in Split Shrine” to visit the Shrine’s grounds and Basilica. -

Integrated Action Plan City of Zagreb

Integrated Action Plan City of Zagreb Zagreb, May 2018 Photo: Zagreb Time Machine - M. Vrdoljak Property of The Zagreb Tourist Board Zagreb Economy Snapshot HOME TO ZAGREB 790 017 19,2% GENERATED PEOPLE OF THE CROATIAN 33,4% MEN 48,3% POPULATION OF NATIONAL GDP WOMEN 51,7% LIVE IN ZAGREB TOTAL ZAGREB GDP 14 876 MIL EUR 377 502 1.2 ZAGREB: JOBS, WITH AN MILLION VISITORS BEST CHRISTMAS UNEMPLOYMENT TOTAL IN 2017 MARKET IN EUROPE RATE @ 5,1% 203.865 DOMESTIC VISITORS, 137.160 NON- DOWN FROM EUROPEAN 10% IN 2005 VISITORS SmartImpact: City of Zagreb IAP SmartImpact: City of Zagreb IAP Executive Summary As in most other cities within the URBACT network, the objective and biggest challenge of the urban The funding scheme is based on a combination of existing proven and innovative financing and development of Zagreb is to provide efficient and cost-effective service to citizens and businesses. procurement methods. The majority of the measures in the IAP are also included as measures previously mentioned in other major programmes and plans of City of Zagreb and are being SmartImpact project aims at exploring and developing innovative management tools for financed by the city budget. However, the application for EU funding that has been used before municipalities to finance, build, manage and operate a smart city by developing approaches that will be necessary for the IAP implementation as well. New forms of public-private collaboration for support decision making, investments, management and maintenance of smart solutions to achieve smart city investments and innovation-based procurement are included in IAP measures, actions the city’s development goals. -

The Origins of Old Catholicism

The Origins of Old Catholicism By Jarek Kubacki and Łukasz Liniewicz On September 24th 1889, the Old Catholic bishops of the Netherlands, Switzerland and Germany signed a common declaration. This event is considered to be the beginning of the Union of Utrecht of the Old Catholic Churches, federation of several independent national Churches united on the basis of the faith of the undivided Church of the first ten centuries. They are Catholic in faith, order and worship but reject the Papal claims of infallibility and supremacy. The Archbishop of Utrecht a holds primacy of honor among the Old Catholic Churches not dissimilar to that accorded in the Anglican Communion to the Archbishop of Canterbury. Since the year 2000 this ministry belongs to Archbishop JorisVercammen. The following churches are members of the Union of Utrecht: the Old Catholic Church of the Netherlands, the Catholic Diocese of the Old Catholics in Germany, Christian Catholic Church of Switzerland, the Old Catholic Church of Austria, the Old Catholic Church of the Czech Republic, the Polish-Catholic Church and apart from them there are also not independent communities in Croatia, France, Sweden, Denmark and Italy. Besides the Anglican churches, also the Philippine Independent Church is in full communion with the Old Catholics. The establishment of the Old Catholic churches is usually being related to the aftermath of the First Vatican Council. The Old Catholic were those Catholics that refused to accept the doctrine of Papal Infallibility and the Universal Jurisdiction. One has to remember, however, that the origins of Old Catholicism lay much earlier. We shouldn’t forget, above all, that every church which really deserves to be called by that name has its roots in the church of the first centuries. -

Anticorruption Policy in Croatia: Benchmark for Eu

1 Damir Grubiša Anti-Corruption Policy in Croatia: a Benchmark for EU Accession In 1998, the European Commission concluded in its evaluation of the central and east European countries' requests for EU membership in the context of the preparation for Agenda 2000 that the fight against political corruption in these countries needed to be upgraded. The Commission's report on the progress of each candidate country can be summed up as follows: "The efforts undertaken by candidate countries are not always adequate to the entity of the problem itself. Although some of these countries initiate new programmes for the control and prevention of corruption, it is too early for a judgment on the efficiency of such measures. A lack of determination can be seen in confronting this problem and in rooting out corruption in the greatest part of the candidate countries". Similar evaluations were repeated in subsequent reports on the progress of candidate countries from central and east Europe. Accordingly, it was concluded in 2001 that political corruption is a serious problem in five out of ten countries of that region: Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Poland, Romania and Slovakia, and a constant problem in three more countries: Hungary, Lithuania and Latvia. The Commission refrained from expressing critical remarks only in the case of two countries – Estonia and Slovenia. Up to 2002, only eight out of fifteen member states ratified the basic instrument that the EU had adopted against corruption, namely the EU Convention on the Safeguarding of Economic Interests of the European Communities. Some of the founding members of the European Community were rated as countries with a "high level of corruption" – Germany, France and, specifically, Italy. -

Fiscal Austerity in Croatia

INTERNATIONAL POLICY ANALYSIS No More Buying Time: Fiscal Austerity in Croatia VELIMIR ŠONJE September 2012 n In the initial phase of the crisis (2008–2010) the HDZ-led centre-right government allowed a wider fiscal deficit and strong growth in public debt, although they cut public infrastructure programmes and introduced new taxes. The idea was to buy time in order not to cut public sector wages, subsidies and transfers. This fiscal strat- egy proved to be wrong as GDP recorded one of the sharpest contractions in Europe in this period. n The new SDP-led centre-left government that took office in January 2012 faced two real threats: exploding public debt and a deterioration in credit ratings. In order to cope with these threats, the new government initiated stronger fiscal adjustment on the expenditure side. n The »austerity vs. growth« debate does not seem to be a good intellectual frame- work for thinking about policies in the case of Croatia, as postponing austerity re- quires finding someone to finance the deficit at low interest rates. That may be impossible for the time being, so some degree of austerity seems to be a necessity in Croatia. VELIMIR ŠONJE | NO MORE BUYING TIME: FISCAL AUSTERITY IN CROATIA Introduction est rates, postponement of fiscal adjustment may lead to a vicious circle of ever growing interest rates. It is easy to find reasons for postponing fiscal austerity. One may fear the weakening of the welfare state. One In countries with such characteristics, governments may argue that fiscal multipliers in a recession are high, have to show fiscal prudence earlier than in the most so spending cuts may deepen the recession (IMF 2012). -

The Path of Orthodoxy the Official Publication of the the Serbian Orthodox Church in North, Central and South America

Volume 56, No. 2 • Spring 2021 Стаза Православља The Path of Orthodoxy The Official publication of the The Serbian Orthodox Church in North, Central and South America “There was a man…” St. Nicholai: His Final Years at St. Tikhon’s Seminary Стаза Православља Volume 56, No. 2 Spring 2021 The Path of Orthodoxy 3 The communique of the Holy Assembly of Bishops 5 St. Nicholai: His Final Years at St. Tikhon’s Seminary 9 Ordination and Tonsures at the St. Elijah Parish in Aliquippa 11 Saint Sava Cathedral Receives the Lucy G. Moses Award from the NY Landmarks Conservancy 12 Frequent attacks and provocations of Serbian Orthodox Churches With the Blessings of the Episcopal Council in Kosovo and Metohija Continue The Path of Orthodoxy 14 Protopresbyter-Stavrophor +Dragoljub C. Malich Reposed The Official Publication of the Serbian in the Lord on April 19, 2021 Orthodox Church in North, Central and South America 16 Archimandrite Danilo (Jokic) Reposed in the Lord Editorial Staff V. Rev. Milovan Katanic 1856 Knob Hill Road, San Marcos, CA 92069 • Phone: 442-999-5695 [email protected] 17 Његова Светост Патријарх српски Господин Порфирије V. Rev. Dr. Bratso Krsic 3025 Denver Street, San Diego, CA 92117 Интервју за РТС – „Упитник” (I Део) Phone: 619-276-5827 [email protected] 23 Саопштење за јавност Светог Архијерејског Сaбора V. Rev. Thomas Kazich P.O. Box 371, Grayslake, IL 60030 25 Двадесет година од упокојења Епископа шумадијског Phone: 847-223-4300 [email protected] Г. Саве (Вуковића) Technical Editor 28 Свети Кнез Лазар и Косовски Завет: Лазаре мудри, молимо те Denis Vikic [email protected] 29 Сени великог архијереја The Path of Orthodoxy is a quarterly publication.