Social Fragmentation in Indonesia: a Crisis from Suharto’S New Order

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

50 Years Since 30 September, 1965: the Gradual Erosion of a Political Taboo

ISSUE: 2015 NO.66 ISSN 2335-6677 RESEARCHERS AT ISEAS – YUSOF ISHAK INSTITUTE SHARE THEIR UNDERSTANDING OF CURRENT EVENTS Singapore | 26 November 2015 50 Years since 30 September, 1965: The Gradual Erosion of a Political Taboo. By Max Lane* EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This year marks the 50th anniversary of the events of 30 September, 1965 and its aftermath. Amidst heightened discussion of the matter, President Widodo, on behalf of his government, stated that there would be no state expression of being sorry for the large scale massacres of 1965. He attended conventional activities on the anniversary consistent with the long-term narrative originating from the period of Suharto’s New Order. At the same time, there are signs of a gradual but steady erosion of the hegemony of the old narrative and an opening up of discussion. This is not driven by deliberate government policy, although some government decisions have facilitated the emergence of a generation for whom the hegemonic narrative holds less weight. The processes weakening the old hegemony have also been fostered by: a) Increased academic openness on the history of the period, both in and outside of Indonesia. b) More activity by lawyers, activists, researchers as well as former political prisoners demanding state recognition of human rights violations in 1965 and afterwards. c) A general attitude to educational processes no longer dominated by indoctrination concerns. 1 ISSUE: 2015 NO.66 ISSN 2335-6677 Hegemony may be slowly ending, but it is not clear what will replace it. *Max Lane is Visiting Senior Fellow with the Indonesia Studies Programme at ISEAS- Yusof Ishak Institute, and has written hundreds of articles on Indonesia for magazines and newspapers. -

Perspective of the 1945 Constitution As a Democratic Constitution Hotma P

Comparative Study of Post-Marriage Nationality Of Women in Legal Systems of Different Countries http://ijmmu.com [email protected] International Journal of Multicultural ISSN 2364-5369 Volume 7, Issue 1 and Multireligious Understanding February, 2020 Pages: 779-792 A Study on Authoritarian Regime in Indonesia: Perspective of the 1945 Constitution as a Democratic Constitution Hotma P. Sibuea1; Asmak Ul Hosnah2; Clara L. Tobing1 1 Faculty of Law University Bhayangkara Jakarta, Indonesia F2 Faculty of Law University Pakuan, Indonesia http://dx.doi.org/10.18415/ijmmu.v7i1.1453 Abstract The 1945 Constitution is the foundation of the constitution of Indonesia founded on the ideal of Pancasila that comprehend democratic values. As a democratic constitution, the 1945 Constitution is expected to form a constitutional pattern and a democratic government system. However, the 1945 Constitution has never formed a state structure and a democratic government system since it becomes the foundation of the constitution of the state of Indonesia in the era of the Old Order, the New Order and the reform era. Such conditions bear the question of why the 1945 Constitution as a democratic constitution never brings about the pattern of state administration and democratic government system. The conclusion is, a democratic constitution, the 1945 Constitution has never formed a constitutional structure and democratic government system because of the personal or group interests of the dominant political forces in the Old Order, the New Order and the reformation era has made the constitutional style and the system of democratic governance that cannot be built in accordance with the principles of democratic law reflected in the 1945 Constitution and derived from the ideals of the Indonesian law of Pancasila. -

Reconceptualising Ethnic Chinese Identity in Post-Suharto Indonesia

Reconceptualising Ethnic Chinese Identity in Post-Suharto Indonesia Chang-Yau Hoon BA (Hons), BCom This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Social and Cultural Studies Discipline of Asian Studies 2006 DECLARATION FOR THESES CONTAINING PUBLISHED WORK AND/OR WORK PREPARED FOR PUBLICATION This thesis contains sole-authored published work and/or work prepared for publication. The bibliographic details of the work and where it appears in the thesis is outlined below: Hoon, Chang-Yau. 2004, “Multiculturalism and Hybridity in Accommodating ‘Chineseness’ in Post-Soeharto Indonesia”, in Alchemies: Community exChanges, Glenn Pass and Denise Woods (eds), Black Swan Press, Perth, pp. 17-37. (A revised version of this paper appears in Chapter One of the thesis). ---. 2006, “Assimilation, Multiculturalism, Hybridity: The Dilemma of the Ethnic Chinese in Post-Suharto Indonesia”, Asian Ethnicity, Vol. 7, No. 2, pp. 149-166. (A revised version of this paper appears in Chapter One of the thesis). ---. 2006, “Defining (Multiple) Selves: Reflections on Fieldwork in Jakarta”, Life Writing, Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 79-100. (A revised version of this paper appears in a few sections of Chapter Two of the thesis). ---. 2006, “‘A Hundred Flowers Bloom’: The Re-emergence of the Chinese Press in post-Suharto Indonesia”, in Media and the Chinese Diaspora: Community, Communications and Commerce, Wanning Sun (ed.), Routledge, London and New York, pp. 91-118. (A revised version of this paper appears in Chapter Six of the thesis). This thesis is the original work of the author except where otherwise acknowledged. -

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY of ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University Ofhong Kong

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY OF ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University ofHong Kong Asia today is one ofthe most dynamic regions ofthe world. The previously predominant image of 'timeless peasants' has given way to the image of fast-paced business people, mass consumerism and high-rise urban conglomerations. Yet much discourse remains entrenched in the polarities of 'East vs. West', 'Tradition vs. Change'. This series hopes to provide a forum for anthropological studies which break with such polarities. It will publish titles dealing with cosmopolitanism, cultural identity, representa tions, arts and performance. The complexities of urban Asia, its elites, its political rituals, and its families will also be explored. Dangerous Blood, Refined Souls Death Rituals among the Chinese in Singapore Tong Chee Kiong Folk Art Potters ofJapan Beyond an Anthropology of Aesthetics Brian Moeran Hong Kong The Anthropology of a Chinese Metropolis Edited by Grant Evans and Maria Tam Anthropology and Colonialism in Asia and Oceania Jan van Bremen and Akitoshi Shimizu Japanese Bosses, Chinese Workers Power and Control in a Hong Kong Megastore WOng Heung wah The Legend ofthe Golden Boat Regulation, Trade and Traders in the Borderlands of Laos, Thailand, China and Burma Andrew walker Cultural Crisis and Social Memory Politics of the Past in the Thai World Edited by Shigeharu Tanabe and Charles R Keyes The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I PRESS HONOLULU Editorial Matter © 2002 David Y. -

INDONESIA's FOREIGN POLICY and BANTAN NUGROHO Dalhousie

INDONESIA'S FOREIGN POLICY AND ASEAN BANTAN NUGROHO Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia September, 1996 O Copyright by Bantan Nugroho, 1996 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibbgraphic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant a la National Lïbraiy of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distn'buer ou copies of this thesis in microfom, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous papa or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/fïim, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substautid extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. DEDICATION To my beloved Parents, my dear fie, Amiza, and my Son, Panji Bharata, who came into this world in the winter of '96. They have been my source of strength ail through the year of my studies. May aii this intellectual experience have meaning for hem in the friture. TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents v List of Illustrations vi Abstract vii List of Abbreviations viii Acknowledgments xi Chapter One : Introduction Chapter Two : indonesian Foreign Policy A. -

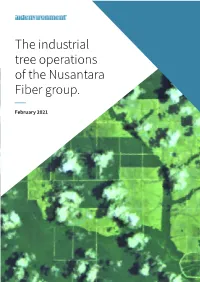

The Industrial Tree Operations of the Nusantara Fiber Group

The industrial tree operations of the Nusantara Fiber group. February 2021 Colofon The industrial tree operations of the Nusantara Fiber group This report is part of the project 'Corporate Transformation in Indonesia's Pulp & Paper Sector' Supported by Good Energies Foundation www.goodenergies.org February 2021 Contact: www.aidenvironment.org/pulpandpaper/ [email protected] Front page image: Forest clearing by Nusantara Fiber's plantation company PT Industrial Forest Plantation Landsat 8 satellite image, early October 2020 Images: Images of Industrial Forest Plantations used in the report were taken with the support of Earth Equalizer www.facebook.com/earthqualizerofficial/ Graphic Design: Grace Cunningham www.linkedin.com/in/gracecunninghamdesign/ Aidenvironment Barentszplein 7 1013 NJ Amsterdam The Netherlands + 31 (0)20 686 81 11 www.aidenvironment.org [email protected] Aidenvironment is registered at the Chamber of Commerce of Amsterdam in the Netherlands, number 41208024 Contents The industrial tree operations of the Nusantara Fiber group | Aidenvironment Executive summary p. 6 Conclusions and recommendations p. 8 Introduction p. 11 CHAPTER ONE Company profile 1 Nusantara Fiber group: company profile p. 12 1.1 Industrial tree concessions p. 13 1.2 Company structure p. 14 CHAPTER TWO Deforestation 2 Deforestration by the Nusantara Fiber group p. 16 for industrial 2.1 Forest loss of 26,000 hectares since 2016 p. 18 trees 2.2 PT Industrial Forest Plantation p. 20 2.3 PT Santan Borneo Abadi p. 22 2.4 PT Mahakam Persada Sakti p. 25 2.5 PT Bakayan Jaya Abadi p.26 2.6 PT Permata Hijau Khatulistiwa p.27 CHAPTER THREE Palm oil 3 The palm oil businesses of Nusantara Fiber directors p. -

Contemporary History of Indonesia Between Historical Truth and Group Purpose

Review of European Studies; Vol. 7, No. 12; 2015 ISSN 1918-7173 E-ISSN 1918-7181 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Contemporary History of Indonesia between Historical Truth and Group Purpose Anzar Abdullah1 1 Department of History Education UPRI (Pejuang University of the Republic of Indonesia) in Makassar, South Sulawesi, Indonesia Correspondence: Anzar Abdullah, Department of History Education UPRI (Pejuang University of the Republic of Indonesia) in Makassar, South Sulawesi, Indonesia. E-mail: [email protected] Received: May 28, 2015 Accepted: October 13, 2015 Online Published: November 24, 2015 doi:10.5539/res.v7n12p179 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/res.v7n12p179 Abstract Contemporary history is the very latest history at which the historic event traces are close and still encountered by us at the present day. As a just away event which seems still exists, it becomes controversial about when the historical event is actually called contemporary. Characteristic of contemporary history genre is complexity of an event and its interpretation. For cases in Indonesia, contemporary history usually begins from 1945. It is so because not only all documents, files and other primary sources have not been uncovered and learned by public yet where historical reconstruction can be made in a whole, but also a fact that some historical figures and persons are still alive. This last point summons protracted historical debate when there are some collective or personal memories and political consideration and present power. The historical facts are often provided to please one side, while disagreeable fact is often hidden from other side. -

Yayasan-Yayasan Soeharto Oleh George Junus Aditjondro

Tempointeraktif.com - Yayasan-Yayasan Soeharto oleh George Junus Aditjondro Search | Advance search | Registration | About us | Careers dibuat oleh Radja:danendro Home Budaya Nasional Digital Berita Terkait Ekonomi Yayasan-Yayasan Soeharto oleh George Mahasiswa Serentak Kenang Tragedi Iptek • Junus Aditjondro Trisakti Jakarta Jum'at, 14 Mei 2004 | 19:23 WIB • Kesehatan Soeharto Memburuk Nasional • BEM Se-Yogya Tolak Mega, Akbar, Nusa TEMPO Interaktif : Wiranto, dan Tutut Olahraga • Asvi: Ada Polarisasi di Komnas HAM Majalah BERAPA sebenarnya kekayaan keluarga Suharto dari yayasan- soal Kasus Soeharto yayasan yang didirikan dan dipimpin Suharto dan Pemeriksaan Kesehatan Soeharto Koran • keluarganya, dari saham yayasan- yayasan itu dalam Belum Jelas Pusat Data berbagai konglomerat di Indonesia dan di luar negeri? • Kejaksaan Lanjutkan Perkara Setelah Tempophoto Soeharto Sehat Narasi Pertanyaan ini sangat sulit dijawab oleh "orang luar". LSM: Selidiki Pelanggaran HAM • English Kesulitan melacak kekayaan semua yayasan itu diperparah Soeharto oleh tumpang-tindihnya kekayaan keluarga Suharto dengan • Komnas HAM: Lima Pelanggaran HAM kekayaan sejumlah keluarga bisnis yang lain, misalnya tiga Berat di Masa Soeharto keluarga Liem Sioe Liong, keluarga Eka Tjipta Widjaya, dan • Pengacara Suharto: Kejari Kurang keluarga Bob Hasan. Kerjaan • Mahasiswa Mendemo KPU Tapi jangan difikir bahwa keluarga Suharto hanya senang >selengkapnya... menggunakan pengusaha-pengusaha keturunan Cina sebagai operator bisnisnya. Sebab bisnis keluarga Suharto juga sangat tumpang tindih dengan bisnis dua keluarga keturunan Referensi Arab, yakni Bakrie dan Habibie. Keluarga Bakrie segudang kongsinya dengan keluarga Suharto, a.l. dengan Bambang • Yayasan-Yayasan Soeharto oleh dan Sudwikatmono dalam bisnis minyak mentah Pertamina George Junus Aditjondro lewat Hong Kong (Pura, 1986; Toohey, 1990: 8-9; Warta • Biodata Soeharto Ekonomi , 30 Sept. -

Only Yesterday in Jakarta: Property Boom and Consumptive Trends in the Late New Order Metropolitan City

Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 38, No.4, March 2001 Only Yesterday in Jakarta: Property Boom and Consumptive Trends in the Late New Order Metropolitan City ARAI Kenichiro* Abstract The development of the property industry in and around Jakarta during the last decade was really conspicuous. Various skyscrapers, shopping malls, luxurious housing estates, condominiums, hotels and golf courses have significantly changed both the outlook and the spatial order of the metropolitan area. Behind the development was the government's policy of deregulation, which encouraged the active involvement of the private sector in urban development. The change was accompanied by various consumptive trends such as the golf and cafe boom, shopping in gor geous shopping centers, and so on. The dominant values of ruling elites became extremely con sumptive, and this had a pervasive influence on general society. In line with this change, the emergence of a middle class attracted the attention of many observers. The salient feature of this new "middle class" was their consumptive lifestyle that parallels that of middle class as in developed countries. Thus it was the various new consumer goods and services mentioned above, and the new places of consumption that made their presence visible. After widespread land speculation and enormous oversupply of property products, the property boom turned to bust, leaving massive non-performing loans. Although the boom was not sustainable and it largely alienated urban lower strata, the boom and resulting bust represented one of the most dynamic aspect of the late New Order Indonesian society. I Introduction In 1998, Indonesia's "New Order" ended. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles the Geopolitical-Economy

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The Geopolitical-economy of Infrastructure Development and Financing: Contesting Developmental Futures in Indonesia A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Geography by Dimitar Anguelov 2021 © Copyright by Dimitar Anguelov 2021 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Geopolitical-economy of Infrastructure Development and Financing: Contesting Developmental Futures in Indonesia by Dimitar Anguelov Doctor of Philosophy in Geography University of California, Los Angeles, 2021 Professor Helga Leitner, Co-Chair Professor Eric Sheppard, Co-Chair In the post-2008 global economy infrastructure development and financing have risen to the top of the development agenda, emerging as a contested field for global investments involving seemingly divergent interests, objectives, rationalities and practices. Whereas multilateral development banks such as the World Bank advocate the market-based Public-Private Partnership (PPP) aimed at attracting private finance and deepening marketized governance, China is forging a state-capitalist alternative through its Belt and Road Initiative. These models are far from mutually exclusive. Through a conjunctural approach, this research examines the broader trade and financial interdependencies in which these models are entangled, and the geopolitical and geoeconomic objectives enframing the emergent infrastructure regime. Developing nations caught in the crosscurrents of these approaches and interests face uncertain risks and possibilities. In Indonesia I show how these approaches are grounded in ii infrastructure projects, framed by competition between China and Japan. Specifically, in Jakarta, I examine the coming together of these models, visions and practices as they articulate with the political-economies of city and state, and their path-dependent restructuring precipitated by the speculative 1997 Asian Financial Crisis. -

The Anti Money Laundering Approach

Center for International Forestry Research Center for International Forestry Research CIFOR Occasional Paper publishes the results of research that is particularly significant to tropical forestry. The content of each paper is peer reviewed internally and externally, and published simultaneously on the web in downloadable format (www.cifor.cgiar.org/publications/papers). Contact publications at [email protected] to request a copy. CIFOR Occasional Paper No. 44 Fighting forest crime and promoting prudent banking for sustainable forest management The Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) is a leading international forestry The anti money laundering approach research organization established in 1993 in response to global concerns about the social, environmental, and economic consequences of forest loss and degradation. CIFOR is dedicated to developing policies and technologies for sustainable use and management of forests, and for enhancing the well-being of people in developing countries who rely on tropical forests for their livelihoods. CIFOR is one of the 15 Future Harvest centres of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR). With headquarters in Bogor, Indonesia, CIFOR has regional offices in Brazil, Burkina Faso, Cameroon and Zimbabwe, and it works in over 30 other countries around the world. Bambang Setiono and Yunus Husein CIFOR is one of the 15 Future Harvest centres CIFOR of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) Donors CIFOR Occasional Paper Series The Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) receives its major funding from governments, international development organizations, private 1. Forestry Research within the Consultative Group on International 23. Les Approches Participatives dans la Gestion des Ecosystemes Forestiers foundations and regional organizations. -

Trial by Fire F Orest F Ires and F Orestry P Olicy in I Ndonesia’ S E Ra of C Risis and R Eform

TRIAL BY FIRE F OREST F IRES AND F ORESTRY P OLICY IN I NDONESIA’ S E RA OF C RISIS AND R EFORM CHARLES VICTOR BARBER JAMES SCHWEITHELM WORLD RESOURCES INSTITUTE FOREST FRONTIERS INITIATIVE IN COLLABORATION WITH WWF-INDONESIA & TELAPAK INDONESIA FOUNDATION INDONESIA’S FOREST COVER Notes: (a) Hotspots, showing ground thermal activity detected with the NOAA AVHRR sensor, represent an area of approximately 1 square kilometer. Data from August - December 1997 were processed by IFFM-GTZ, FFPCP (b) Forest cover is from The Last Frontier Forests, Bryant, Nielsen, and Tangley, 1997. "Frontier forest" refers to large, ecologically intact and relatively undisturbed natural forests. "Non-frontier forests" are dominated by eventually degrade the ecosystem. See Bryant, Nielsen, and Tangley for detailed definitions. AND 1997-98 FIRE HOT SPOTS CA, and FFPMP-EU. ondary forests, plantations, degraded forest, and patches of primary forest not large enough to qualify as frontier forest. "Threatened frontier forests" are forests where ongoing or planned human activities will TRIAL BY FIRE F OREST F IRES AND F ORESTRY P OLICY IN I NDONESIA’ S E RA OF C RISIS AND R EFORM CHARLES VICTOR BARBER JAMES SCHWEITHELM WORLD RESOURCES INSTITUTE FOREST FRONTIERS INITIATIVE IN COLLABORATION WITH WWF-INDONESIA & TELAPAK INDONESIA FOUNDATION TO COME Publications Director Hyacinth Billings Production Manager Designed by: Papyrus Design Group, Washington, DC Each World Resources Institute report represents a timely, scholarly treatment of a subject of public concern. WRI takes responsibility for choosing the study topics and guaranteeing its authors and researchers freedom of inquiry. It also solicits and responds to the guidance of advisory panels and expert reviewers.