Are the Ratzinger and Zoghby Proposals Dead

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Council Chapter 12

Chapter 12 ― Ecumenism The Requirements for Union On May 10, 1961, while on a visit to Beirut, the patriarch went to see the apostolic nuncio, Archbishop Egano Righi Lambertini. Among other things, the nuncio asked him what the Orthodox thought of the council. The patriarch answered his question. The nuncio then asked him to transmit his views in writing to the Central Commission. The patriarch did so in a long letter addressed to Archbishop Felici, dated May 19, 1961. 1. It can be affirmed with certainty that the Orthodox people of our regions of the Near East, with few exceptions, have been filled with enthusiasm at the thought of the union that was to be realized by this council. The people as a whole see no other reason for this council than the realization of this union. It must be said that in view of their delicate position in the midst of a Muslim majority, the Christian people of the Arab Near East, perhaps more than those anywhere else, aspire to Christian unity. For them this unity is not only the fulfillment of Our Lord’s desire, but also a question of life or death. During a meeting of rank and file people held last year in Alexandria, which included many Orthodox Christians, who were as enthusiastic as the Catholics in proclaiming the idea of union, we were able to speak these words, “If the union of Christians depended only on the people, it would have been accomplished long ago.” When His Holiness the Pope announced the convocation of this council, our people, whether Orthodox or Catholic, immediately thought spontaneously and irresistibly that the bells were about to ring for the hour of union. -

The Disputed Teachings of Vatican II

The Disputed Teachings of Vatican II Continuity and Reversal in Catholic Doctrine Thomas G. Guarino WILLIAM B. EERDMANS PUBLISHING COMPANY GRAND RAPIDS, MICHIGAN Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. Grand Rapids, Michigan www.eerdmans.com © 2018 Thomas G. Guarino All rights reserved Published 2018 ISBN 978-0-8028-7438-2 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Guarino, Thomas G., author. Title: The disputed teachings of Vatican II : continuity and reversal in Catholic doctrine / Thomas G. Guarino. Description: Grand Rapids : Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2018035456 | ISBN 9780802874382 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Vatican Council (2nd : 1962-1965 : Basilica di San Pietro in Vaticano) | Catholic Church— Doctrines.—History—20th century. Classification: LCC BX830 1962 .G77 2018 | DDC 262/.52—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018035456 Contents Acknowledgments Abbreviations Introduction 1. The Central Problem of Vatican II 2. Theological Principles for Understanding Vatican II 3. Key Words for Change 4. Disputed Topics and Analogical Reasoning 5. Disputed Topics and Material Continuity Conclusion Select Bibliography Index Acknowledgments I would like to express my gratitude, even if briefly and incompletely, to the many people who have aided the research for this book. These include the Rev. Dr. Joseph Reilly, dean of the school of theology of Seton Hall University, for his kind support of this work; Dr. John Buschman, dean of Seton Hall University libraries, for generously providing a suitable space for research and writing; the Rev. Dr. Lawrence Porter, director of Turro library, for his assistance in obtaining the necessary research materials; the faculty and staff of Seton Hall libraries, especially Anthony Lee, Stella Wilkins, Andrew Brenycz, Tiffany Burns, Mabel Wong, Stephania Bennett, Priscilla Tejada, and Damien Kelly, for their competent and friendly assistance; the Dominican friars of St. -

Liturgical Observations on the Second Vatican Council by a Forgotten Catholic

QL 97 (2016) 84-103 doi: 10.2143/QL.97.1.3154577 © 2016, all rights reserved LITURGICAL OBSERVATIONS ON THE SECOND VATICAN COUNCIL BY A FORGOTTEN CATHOLIC The Old Catholic Observer’s Perspective on the Liturgical Developments at the Second Vatican Council Introduction Liturgy played a very important role at the Second Vatican Council, as it expressed the council’s direction, both in terms of ecclesiology and in terms of ecumenism, as well as in general.1 Liturgy was also the topic of the council’s first constitution, Sacrosanctum Concilium (4 December 1963); the document led to some of the most visible changes in ecclesial life following the council, and, because it was produced so early on in the council, it provided a point of reference for further discussions.2 Observers, * I am grateful to Mrs. S.C. Smit-Maan, IJmuiden, for preserving the personal papers of P.J. Maan, on which this paper is based, and for granting me access to them. Thanks are also due to the anonymous reviewers of Questions Liturgiques, who suggested a number of im- provements, and to Mrs. S.G. Geerlof-van de Zande, who was kind enough to correct my English, and to the Rev. Ole van Dongen, MA, who offered many suggestions concerning style and content. 1. See for sketches of the debate at large, on which much has been written: Mathijs Lamberigts, “The Liturgy Debate at Vatican II: An Exercise in Collective Responsibility,” Questions Liturgiques / Studies in Liturgy 95 (2014) 52-67, and Maria Paiano, “Sacrosanc- tum Concilium: La costituzione sulla liturgia del Concilio Vaticano II sotto il profilo sto- rico,” in Rileggere il Concilio: Storici e teologi a confronto, ed. -

P a P E R S Secretariat Forinterreligious Dialogue;Curias.J.,C.P.6139,00195Romaprati, Italy; Tel

“Ecumenism: Hopes and Challenges for the New Century” The 16TH International Congress of Jesuit Ecumenists P A E R S Maryut Retreat House, Alexandria, Egypt 4-12 July 2001 Secretariat for Interreligious Dialogue; Curia S.J., C.P. 6139, 00195 Roma Prati, Italy; tel. (39)-06.689.77.567/8; fax: 06.687.5101; e-mail: [email protected] JESUIT ECUMENISTS MEET IN ALEXANDRIA Daniel Madigan, S.J. A full programme, oganized expertly by Henri Boulad (PRO), kept the 30 particpants (from all six continents) busy throughout the working days and evenings, and on the Sunday the group was able to visit the Coptic Orthodox Monastery of St. Makarios. A message from Fr. General underlined the importance of the ecumenical venture among the Society's priorities, and a select number of the participants had been involved with the group since its inception. The agenda ranged widely, focussing in part on ecumenical issues in the complex ecclesial reality of the Middle East, but also on recent developments in the wider ecumenical sphere. We had the opportunity to meet with clergy and laypeople from the Coptic Orthodox and Coptic Evanglical churches, as well as with Muslims. Jacques Masson (PRO) and Christian van Nispen (PRO), with their long years of experience and study of the Church in Egypt introduced us to various of its aspects. Jacques Masson surveyed some of the ecumenical history of the oriental Churches and agreements reached especially among the Chalcedonian and non- Chalcedonian churches in recent years. Victor Chelhot (PRO) from Damascus presented developments in the local attempts to remove the obstacles to unity between the Greek Catholic and Greek Orthodox Churches of Antioch. -

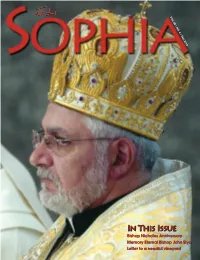

IN This ISSUE in This ISSUE

VOL. 49 | NO. 4 | FALL 2019 In This Issue Bishop Nicholas Anniversary Memory Eternal Bishop John Elya Letter to a needful vineyard CONTENTS ophia SThe Journal of the Eparchy of Newton 3 50 Years in the Service of Our Lord for Melkite Catholics in the United States www.melkite.org 7 Memory Eternal Elya, Youssef and Hull Published quarterly by the Eparchy of Newton. ISSN 0194-7958. 10 Letters to the Editor Made possible in part by the Catholic Home Mission Committee, a bequest by the Rev. Allen Maloof and generous supporters of the annual Bishop’s Appeal. 11 SOPHIA - an award winning magazine MEMBER CATHOLIC PRESS ASSOCIATION 12 Holy Land Churches are more than a pilgrimage PUBLISHER Most Rev. Nicholas J. Samra, Eparchial Bishop 14 Campaign to bring food, medicine to Syria EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Archimandrite James Babcock 15 Annual Synod of Melkite Catholic Bishops COPY EDITOR 16 Eden to Eden: A 70-year retreat Jim Trageser 18 Letter to a Needful Vineyard DESIGN AND LAYOUT Doreen Tahmoosh-Pierson 20 Why I take my kids to church SOPHIA ADVISORY BOARD Archimandrite Fouad Sayegh 21 Orientale Lumen Conference Archimandrite Michael Skrocki Fr Thomas Steinmetz | Fr Hezekias Carnazzo 22 Why I Decided to become Eastern Catholic Cary Rosenzweig 23 Pope Francis gives Orthodox patriarch relics SUBSCRIPTIONS/DISTRIBUTION Please send subscription changes to your parish office. If you are not registered 24 Pope Francis Beatifies7 Romanian martyrs in a parish please send changes to: Eparchy of Newton 26 The Power of the Cross 3 VFW Pky, West Roxbury, MA 02132 27 Melkite Catholic young adults find hope The Publisher waives all copyright to this issue. -

Initiative of Archbishop Elias (Zoghby)

r Eastern Churches Journal, Vol. 2 NO.2 Eastern Churches Journal is published by the Society ofSaint Contents John Chrysostom, and discusses Eastern Christian Churches. 1 ISSN 1354·0580 From the Editor Patron: His Holiness Maximos V The Catholic - Orthodox Theological Dialogue Greek-Catholic Patriarch of Antioch, Alexandria, • Initiative ofArchbishop Elias (Zoghby) 11 Jerusalem and all the East ,gt( In Memoriam: E. J. B. Fry and Dom Bede Winslow fOb • Patriarch Bartholomew regarding the 29 Editor: Serge Keleher Eastern Catholic Churches Editorial Board: Bishop KaIlistos ofDiokleia, Bishop Vsevolod of E"}7 • Traditions Regarding the Procession ofthe 35 Scopelos, Bishop Rowan Williams ofMonmouth, Holy Spirit Brother Elias O. Carm, Jack Figel,Andrew 47 Onuferko, Donal Savage, Vincent Saverino, • US Catholic and Orthodox Bishops Visit Graham Woolfenden, Roman Yereniuk Rome and Istanbul Editor Emeritus of Chrysostom: Helle Georgiadis • Reconciliation and Ecclesiology ofSister Churches 55 by Waclaw Hryniewicz The ECJ Advisory Board is listed on page 10. Christological Issues in the Raising ofLazarus 73 The aims of the Society of Saint John Chrysostom, founded in 1926, by Hierodeacon Patapios are to make known the history, worship, spirituality, discipline and 91 theology of Eastern Christendom, and to work and pray that all Chris A Visit to Lebanon and Syria tians, particularly the Eastern Churches, may find full communion with by Serge Keleher one another to attain that fullness of unity which Jesus Christ desires. Liturgical L/ltinization 105 Articles, reviews, and letters express the views oftheir authors and do by Graham Woolfenden not necessarily reflect the opinions of the Editors, or of the Society. -

Greek Melkite Catholic Patriarchate of Antioch: Birth, Evolution, and Current Orientations

GREEK MELKITE CATHOLIC PATRIARCHATE OF ANTIOCH: BIRTH, EVOLUTION, AND CURRENT ORIENTATIONS Abdallah Raheb, BAO translated by Nicholas J. Samra It would be very simplistic to approach the question of the existence of the Greek Melkite Catholic Patriarchate of Antioch by beginning with Cyril Tanas, the first juridical Catholic Melkite Patriarch, who was elected and consecrated in 1724. In order to dissipate the confusion on the subject of this patriarchate, which most easterners and westerners want to consider a purely “national” Church, let us begin by its identification. 1) WHO ARE THE MELKITES? Without entering into the complex question of the ethnology1 of the Melkites, it is sufficient to state exactly that the name “Melkite” was applied by the Monophysites to all the followers of the Council of Chalcedon (451) from the three Patriarchates of Alexandria, Antioch and Jerusalem2 without distinction of Greek or Syrian race.3 Thus we see that it was not only an exclusive designation for the Greek Catholics of the three mentioned patriarchates, but also for all Greek speaking and Arabic speaking faithful of these three patriarchates of the Byzantine rite.4 Recently valid experts of their history have tried to give an exact name to those who are called Melkite Catholics. In an excellent study, Rev. Peter Rai5 prefers the name “Orthodox-Catholic”6 but only in their 1 Cf. on this subject, Karalevskij: “Origines ethnologiques du peuple melkite” in DHGE (Dictionnaire d'Histoire et de Géographie Ecclesiastique), Vol. III, col. 585-589. Also C. Charon (=Karalevskij, Korolevskij or Korolevsky): “L’origine ethnologique des Melkites,” in Echos d’Orient, 1908, Vol. -

Fall, 2010 Chrysostom Western Region Workshop

Happenings! Music & Chant Part I, Light of the East Western Theory, Newsletter of the Society of Saint John Chrysostom Development & Praxis Western Region Edition Saturday, November 13, 10 a.m. -1 p.m. A Society of St. John Volume 5, Number 1 Fall, 2010 Chrysostom Western Region workshop. St. Michael Norber- tine Abbey, 19292 El Toro Road, Silverado, CA 92676. Presenters: Prior Hugh Barbour, Fr. Jerome Steps to Unity, Steps to Molokie, and Fr. Chrysostom Baer. A free will offering will be taken. A SSJC-WR meeting will Common Witness follow. Lunch will be provided by the Abbey following the celebra- Catholic/Orthodox Light of the East Conference set for tion of Sext. A question and an- February, 5, 2011 at St. Paul Orthodox Church, Irvine swer program will follow after lunch. A “Light of the East” Society of St. John Advance registration is required. A $20 Mary, Mother of God: Chrysostom, Western-Region Conference, donation is requested for the day, 9 a.m.- 4 Bridge to Unity Steps to Unity; Steps to Common Witness , p.m., which includes lunch.. featuring nationally known participants in Greek Orthodox Metropolitan Gerasimos A conversation on the Orthodox-Catholic dialogue, Fr. Ron of San Francisco, Roman Catholic Bishop Virgin Mary in Eastern & Roberson, Associate Director of the Tod Brown of Orange, and Melkite-Greek Western Christianity USCCB Secretariat for Ecumenical and Catholic Bishop Nicholas Samra will be in Interreligious Affairs, and Fr. Thomas Fitz- attendance. Wednesday, November 17, 6 p.m.: Reception; 7 p.m.: Lecture. Loyola Gerald, Dean of Holy Cross Greek Ortho- The two national speakers will discuss Marymount University, University dox School of Theology, Brookline, MA Steps to Unity in the morning session. -

Letter from Rome on the Zoghby Initiative

From : BISHOP NICHOLRS SRMRR VICRR GENERRL 81EI-558-0144 Dec.16.1997 EI3:32 PM PEI2 5.01 k/ Y. l,., r.. 1 1 1997 C: 0 N C; R t; c; A 'r ('1 juin . .. 25.1/7$ J'll<)l. N. h'<l~~~~~r~rilif*. ira. nilinvnii. Iiiiiiim r,iiiiti.ii ii. t,,* ii..,iiil,,i,i,ir $1 ll-ftu '1s si411rc *IUCS~U~!u~tn*rm n~ll,, *i,fa,nq~,z la tiouvcllc du projet de rapprochement entre le Patriarcat Grec-Melkite Catholique et le Fatriarcai Ortliodoxc d' Antioclie a suscitb des &hm et des coniinencaires dans l'opinion publique. la C:oiigr&patiori poiir la Doctrine de la Foi, la C:otigrégati<~iipour les Eglises Orientales ct le Coiiscil Pontifical pour I'tliiitt! des Chrbtiens se sorit cf'fcirçts dc coririaltre dc plus pres, ct d'cxarniiier avec atteiitioti, Its questions de leur carnp6tence en ce dotnaine ; et les respclnssbles de ces I3icastéres ont reçu du Ssitit-Père la char~èd'exprimer $ Votre Béntitudc qiielques coiisidératiotis. Ix Saitii-Siègc siiii avec vif intér&t et entend enco,urager tes irii~iaiivesteiidaiit & favoriser Ir chciiiiii de plciiic r6cc11icit iatioii cles Eglises chr&tiérines.II apptecie les riiotivatiotis cle l'effort ciitrepris ilepuis dcs cléceiirii~:~par 1~ I'atriarcat Grec-Melkite Catholique, qui tctitc d'accélérer I'nvEiietnent de cette plériitudc dc cor?irt~uiiiorisi dhsirbc. Le Code dés Canoiis des Egliscs I'lriciitales recciiinait lh uii devoir clc cliaque chrkticti IC.:iiii, 902), qiii devient pour les Eglises Oriciitales çatlioliqucs uii sfrhcizil nlurius (~aili. 9031, dont l'exercice sera rCglP "iiorinis specialibus iuris pariicularis rnorleratite euridcin inotuin Sede b Apnstnlim Roilialia pro iiriiversa Rcclesia" (cari. -

Studies on the Byzantine Liturgy - 1

Studies on the Byzantine Liturgy - 1 The Draft Translation: A Response to the Proposed Recasting of the Byzantine-Ruthenian Divine Liturgy of Saint John Chrysostom Serge Keleher 2006 Copyright © 2006 Serge Keleher Stauropegion Press PO Box 11096 Pittsburgh, PA 15237‐9998 ii This small work is dedicated to Metropolitan Joseph (Raya) Archbishop of St. Jean d’Acre, Haifa, Nazareth and All Galilee Who fell asleep in the Lord on 10 June 2005 as this work was nearing completion. “For though you have countless guides in Christ, you do not have many fathers. For I became your father in Christ Jesus through the Gospel.” I Corinthians 4:14‐15 May Archbishop Joseph’s Memory be Eternal! iii iv Exordium: For a number of reasons, including the need to avoid any fresh differences with our separated brothers, the Eastern Catholic Church must avoid any idea of adapting its rites without prior agreement with the corresponding branches of the Orthodox Church. We must not allow the adaptation of the liturgy to become an obsession. The liturgy, like the inspired writings, has a permanent value apart from the circumstances giving rise to it. Before altering a rite we should make sure that a change is strictly necessary. The liturgy has an impersonal character and also has universality in space and time. It is, as it were, timeless and thus enables us to see the divine aspect of eternity. These thoughts will enable us to understand what at first may seem shocking in some of the prayers of the liturgy – feasts that seem no longer appropriate, antiquated gestures, calls to vengeance which reflect a pre‐Christian mentality, anguished cries in the darkness of the night, and so on. -

Conversations with Lubomyr Cardinal Husar Ukrainian Catholic University

CONVERSATIONS WITH LUBOMYR CARDINAL HUSAR UKRAINIAN CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF ECUMENICAL STUDIES Antoine Arjakovsky CONVERSATIONS WITH LUBOMYR CARDINAL HUSAR Towards a Post-Confessional Christianity UKRAINIAN CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY PRESS LVIV 2007 UDC 261.8 Antoine Arjakovsky. Conversations with Lubomyr Cardinal Husar: Towards a Post- Confessional Christianity / translated from French. Lviv: Ukrainian Catholic University Press 2007. 160 p., ill. ISBN 966-8197-22-4. Translations Antoine Arjakovsky, Marie-Aude Tardivo, Lida Zubytska Editors Andrew Sorokowski, Michael Petrowycz Project manager Marie-Aude Tardivo Photos Petro Didula, Yurii Helytovych, Hryhorii Prystai, Volodymyr Shchurko Pictures from childhood and youth of Cardinal Husar courtesy of Maria Rypan Сopyright © 2005 by Parole et Silence Сopyright © 2007 by Institute of Ecumenical Studies Ukrainian Catholic University All rights reserved ISBN 966-8197-22-4 UKRAINIAN CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY PRESS vul. I. Sventsitskoho 17, 79011 Lviv telephone/facsimile: (032) 2409496; e-mail: [email protected] www.press.ucu.edu.ua Printing-house of the Lviv Polytechnic National University vul. F. Kolessy, 2, 79000 Lviv Printed in Ukraine Contents FOREWORD by Borys Gudziak, Rector of the Ukrainian Catholic University ................................... 7 CONVERSATIONS Itinerary .........................................................................................21 The Greek-Catholic Church and the Orange revolution .............. 33 The Ukrainian Greek-Catholic Church and the Patriarchate -

Ecumenical Relations and Theological Dialogue Between the Catholic Church and the Orthodox Church

ECUMENICAL RELATIONS AND THEOLOGICAL DIALOGUE BETWEEN THE CATHOLIC CHURCH AND THE ORTHODOX CHURCH Waclaw Hryniewicz The relations between Eastern and Western Christianity have long since been difficult, full of misunderstandings, tensions, conflicts and disappointments. The present-day situation is nothing new in this respect. Many studies, devoted to the history of the schism of the eleventh century, show that it was an outcome of a long process of mutual estrangement between the two Christian traditions.' Many factors contributed to the development of this alienation: cultural (the use of Latin and Greek), political and theological. On theological level one can see the differences in the Trinitarian teaching already in Patristic times, later on in the centuries-long disputes over the Filioque clause, and some ecclesiological issues such as the role of the Bishop of Rome. No wonder that theological controversies were so often permeated with many reproaches of a cultural and political nature. It was easy, in this context, to regard even small differences as serious deviations from the true faith. The second millennium brought such painful events as the Crusades, the sack of Constantinople and the establishment of parallel hierarchies in the East (the Latin Patriarchates of Jerusalem and Constantinople). Only on May 4, 2001, during his visit to the Archbishop of Athens, Christodoulos, Pope John Paul II asked God for forgiveness of the past sins: Some memories are especially painful, and some events of the distant past have left deep wounds in the minds and hearts of people to this day. I am thinking of the disastrous sack of the imperial city of Constantinople (...).