A Gendered Critique of the Catholic Church's Teaching

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amoris Laetitia & Sensus Fidelium

AMORIS LAETITIA & SENSUS FIDELIUM NIHAL ABEYASINGHA WO SYNODS were convoked the Church, but this does not preclude various specifically to discuss the issue of ways of interpreting some aspects of that marriage and family. The end result was teaching or drawing certain consequences from T it. This will always be the case as the Spirit that the prevailing doctrine, usage and understanding of these realities were repeated. guides us towards the entire truth (cf. Jn 16:13), until he leads us fully into the mystery of Christ The bishops gathered together could get no and enables us to see all things as he does. Each further. country or region, moreover, can seek solutions As Pope Francis said in Amoris Laetitia better suited to its culture and sensitive to its (=AL) 2: traditions and local needs. For 'cultures are in The Synod process allowed for an examination fact quite diverse and every general principle… of the situation of families in today's world, needs to be inculturated, if it is to be respected and thus for a broader vision and a renewed and applied' awareness of the importance of marriage and The statement of the Pope that 'time is the family. The complexity of the issues that greater than space' is a reference to Evangelii arose revealed the need for continued open Gaudium #222-225. It is basically a call to give discussion of a number of doctrinal, moral, time for growth, development, to allow God's spiritual, and pastoral questions. The thinking of pastors and theologians, if faithful to the grace to work within individuals and Church, honest, realistic and creative, will help communities. -

Catholics and Jews: and for the Sentiments Expressed

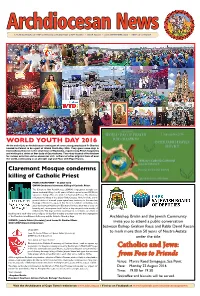

Archdiocesan News A PUBLICATION OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH OF CAPE TOWN • ISSUE NO 81 • JULY-SEPTEMBER 2016 • FREE OF CHARGE WORLD YOUTH DAY 2016 At the end of July an Archdiocesan contingent of seven young people (and Fr Charles) headed to Poland to be a part of World Youth Day 2016. They spent some days in Czestochowa Diocese in the small town of Radonsko, experiencing Polish hospitality and visiting the shrine of Our Lady of Czestochowa. Then they headed off to Krakow for various activities and an encounter with millions of other pilgrims from all over the world, culminating in an all-night vigil and Mass with Pope Francis. Claremont Mosque condemns killing of Catholic Priest PRESS STATEMENT – 26 JULY 2016 CMRM Condemns Inhumane Killing of Catholic Priest The Claremont Main Road Mosque (CMRM) congregation strongly con- demns the brutal killing of an 85 year-old Catholic priest by two ISIS/Da`ish supporters during a Mass at a Church in Normandy, France. The inhumane and gruesome killing of the elderly Father Jacques Hamel and the sacrili- geous violation of a sacred prayer space bears testimony to the merciless ideology of Da`ish. It is apparent that Da`ish is hell-bent on fuelling a reli- gious war between Muslims and Christians. However, their war is a war on humanity and our response should reflect a deep respect for the sanctity of all human life. This tragic incident should spur us to redouble our efforts at reaching out to each other across religious divides. Our thoughts and prayers are with the congregation of the Church in Saint-Etienne-du-Rouvray and the Catholic Church at large. -

Renewing a Catholic Theology of Marriage Through a Common Way of Life: Consonance with Vowed Religious Life-In-Community

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Dissertations (1934 -) Projects Renewing a Catholic Theology of Marriage through a Common Way of Life: Consonance with Vowed Religious Life-in-Community Kent Lasnoski Marquette University Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Lasnoski, Kent, "Renewing a Catholic Theology of Marriage through a Common Way of Life: Consonance with Vowed Religious Life-in-Community" (2011). Dissertations (1934 -). 98. https://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu/98 RENEWING A CATHOLIC THEOLOGY OF MARRIAGE THROUGH A COMMON WAY OF LIFE: CONSONANCE WITH VOWED RELIGIOUS LIFE-IN- COMMUNITY by Kent Lasnoski, B.A., M.A. A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Milwaukee, Wisconsin May 2011 ABSTRACT RENEWING A CATHOLIC THEOLOGY OF MARRIAGE THROUGH A COMMON WAY OF LIFE: CONSONANCE WITH VOWED RELIGIOUS LIFE-IN-COMMUNITY Kent Lasnoski Marquette University, 2011 Beginning with Vatican II‘s call for constant renewal, in light of the council‘s universal call to holiness, I analyze and critique modern theologies of Christian marriage, especially those identifying marriage as a relationship or as practice. Herein, need emerges for a new, ecclesial, trinitarian, and christological paradigm to identify purposes, ends, and goods of Christian marriage. The dissertation‘s body develops the foundation and framework of this new paradigm: a Common Way in Christ. I find this paradigm by putting marriage in dialogue with an ecclesial practice already the subject of rich trinitarian, christological, ecclesial theological development: consecrated religious life. -

The Kingdom of God and the Heavenly- Earthly Church

Letter & Spirit 2 (2006): 217–234 The Kingdom of God and the Heavenly- Earthly Church 1 Christoph Cardinal Schönborn, O. P. 2 “God, who is rich in mercy, out of the great love with which he loved us, has made even us, who were dead through our sins, alive together with Christ. .and he has raised us up with him in Christ Jesus and given us a place with him in the heavens” (Eph. 2:4–6). Christian existence means being with Christ, and thus means being where he is, sitting at the right hand of the Father. The Church has her homeland where Christ is. In terms of her head and of her goal, she is a heavenly Church. Since she is an earthly Church, she knows that she is a pilgrim Church, stretching out to reach her goal. The Second Vatican Council’s Constitution on the Church,Lumen Gentium, contemplated the Church as the people of God. If one reads this great conciliar text as a whole, it is clear that the Council sees the Church as the people of God entirely on the basis of her goal, to be the heavenly, perfected Church (Lumen Gentium, 2). It is only the goal that gives meaning to the path. The Church is the pilgrim people of God, and her goal is the heavenly Jerusalem. It is only when we contemplate the Church in her earthly-heavenly transi- tional existence that we have the whole Church in view. This is why we begin by presenting some witnesses for this way of seeing the Church; then we ask why the sensitivity to this perspective has been largely lost today, and above all why the heavenly dimension of the Church is often forgotten; finally, we should like to indicate some perspectives on how it is possible to regain this vision of the Church as heavenly-earthly reality. -

Council Chapter 12

Chapter 12 ― Ecumenism The Requirements for Union On May 10, 1961, while on a visit to Beirut, the patriarch went to see the apostolic nuncio, Archbishop Egano Righi Lambertini. Among other things, the nuncio asked him what the Orthodox thought of the council. The patriarch answered his question. The nuncio then asked him to transmit his views in writing to the Central Commission. The patriarch did so in a long letter addressed to Archbishop Felici, dated May 19, 1961. 1. It can be affirmed with certainty that the Orthodox people of our regions of the Near East, with few exceptions, have been filled with enthusiasm at the thought of the union that was to be realized by this council. The people as a whole see no other reason for this council than the realization of this union. It must be said that in view of their delicate position in the midst of a Muslim majority, the Christian people of the Arab Near East, perhaps more than those anywhere else, aspire to Christian unity. For them this unity is not only the fulfillment of Our Lord’s desire, but also a question of life or death. During a meeting of rank and file people held last year in Alexandria, which included many Orthodox Christians, who were as enthusiastic as the Catholics in proclaiming the idea of union, we were able to speak these words, “If the union of Christians depended only on the people, it would have been accomplished long ago.” When His Holiness the Pope announced the convocation of this council, our people, whether Orthodox or Catholic, immediately thought spontaneously and irresistibly that the bells were about to ring for the hour of union. -

Are the Ratzinger and Zoghby Proposals Dead

Are the Ratzinger Proposal and Zoghby Initiative Dead? Implications of Ad Tuendam Fidem for Eastern Catholic Identity Joel I. Barstad, Ph.D. Revised April 4, 2008 Introduction Is Rome satisfied with Eastern Catholic loyalty in terms of the Zoghby Initiative? In 2002 this question was submitted several times to various speakers at Orientale Lumen Conference VI, but never received an answer. One of the conference organizers, responsible for communicating audience questions to speakers, remarked that one of the speakers, a Roman Catholic Cardinal and member of the international Orthodox-Catholic dialogue, had declined the question because he did not know what the Zoghby Inititative was. And yet, for many Eastern Catholics, it has had an important part in shaping their understanding of their role as bridges between East and West. Eastern Catholic Hopes Many Eastern Catholics, in the wake of 20th-century improvements in relations between Rome and Constantinople, the ecumenical declarations of Vatican II, and Roman insistence that Eastern Catholic churches recover their authentic liturgical traditions, have found courage to abandon the theological hybridism of uniatism and claim for themselves the identity of Orthodox-in-communion-with-Rome. In this way they have begun to think of themselves, not as Eastern rites within the Roman Catholic Church, but as forerunners of the coming reunion of the Roman Church with the Orthodox sister churches. In the early 1990s, encouraged by the advances represented by the Balamand Statement, the Kievan Church Study Group1 and the Melkite Greek Catholic bishops explored the possibility of double communion whereby Eastern Catholic churches would reestablish communion with their historic Orthodox mother or sister churches without breaking communion with Rome. -

Dignitatis Humanae and the Development of Moral Doctrine: Assessing Change in Catholic Social Teaching on Religious Liberty

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA Dignitatis humanae and the Development of Moral Doctrine: Assessing Change in Catholic Social Teaching on Religious Liberty A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Theology and Religious Studies Of The Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Philosophy By Barrett Hamilton Turner Washington, D.C 2015 Dignitatis humanae and the Development of Moral Doctrine: Assessing Change in Catholic Social Teaching on Religious Liberty Barrett Hamilton Turner, Ph.D. Director: Joseph E. Capizzi, Ph.D. Vatican II’s Declaration on Religious Liberty, Dignitatis humanae (DH), poses the problem of development in Catholic moral and social doctrine. This problem is threefold, consisting in properly understanding the meaning of pre-conciliar magisterial teaching on religious liberty, the meaning of DH itself, and the Declaration’s implications for how social doctrine develops. A survey of recent scholarship reveals that scholars attend to the first two elements in contradictory ways, and that their accounts of doctrinal development are vague. The dissertation then proceeds to the threefold problematic. Chapter two outlines the general parameters of doctrinal development. The third chapter gives an interpretation of the pre- conciliar teaching from Pius IX to John XXIII. To better determine the meaning of DH, the fourth chapter examines the Declaration’s drafts and the official explanatory speeches (relationes) contained in Vatican II’s Acta synodalia. The fifth chapter discusses how experience may contribute to doctrinal development and proposes an explanation for how the doctrine on religious liberty changed, drawing upon the work of Jacques Maritain and Basile Valuet. -

Fall 2016 Issue 45

Fall 2016 Issue 45 Unpacking the ‘soul-sickness’ of racism… Featured Articles Shootings in Texas, Minnesota and Louisiana raise need for engagement, conversation, conversion Gretchen R. Crowe, OSV Newsweekly Unpacking the Soul-sickness of Racism In the aftermath of a Our Journey Continues… turbulent week that saw the Guidelines for Building unprovoked shooting of two Intercultural Competence unarmed black men by white for Ministers police officers in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and Words of Wisdom: What Minneapolis, followed by We Have Seen and Heard the shocking assassination of five uniformed officers in Building Intercultural Dallas by a black man, many Competence Father Bryan Massingale, professor of theological leaders — including those in the Church — have called Celebrating Diversity: Asian and ethics at Fordham University, speaks Nov. 6 in New Orleans. CNS photo/Peter Finney Jr., for a national conversation Pacific Island Catholic Day of Clarion Herald around the topic of race. Reflection In a statement July 8th, Archbishop Joseph E. Kurtz, president of the Understanding Culture U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, called all citizens to a “national reflection.” Multicultural Communication Obstacles to Intercultural “In the days ahead, we will look toward additional ways of nurturing an Relations open, honest and civil dialogue on issues of race relations, restorative justice, mental health, economic opportunity, and addressing the A Vision for Building Intercul- question of pervasive gun violence,” he said. tural Competence In Dallas, Bishop Kevin J. Farrell also called for dialogue. Society of St. Vincent de Paul Collaborates with IAACEC “We cannot lose respect for each other, and we call upon all of our civic Attendees in Louisville leaders to speak to one another and work together to come to a sensible resolution to this escalating violence,” he wrote on his blog July 8th. -

Final Impenitence and Hope Nietzsche and Hope

“Instaurare omnia in Christo” Hope Final Impenitence and Hope Nietzsche and Hope Heaven: Where the Morning Lies November - December 2016 Faith makes us know God: we believe in Him with all our strength but we do not see Him. Our faith, therefore, needs to be supported by the certitude that some day we will see our God, that we will possess Him and willl be united to Him forever. The virtue of hope gives us this certitude by presenting God to us as our infinite good and our eternal reward. Fresco of the five prudent virgins, St. Godehard, Hildesheim, Germany Letter from the Publisher Dear readers, Who has not heard of Pandora’s box? The Greek legend tells us that Pandora, the first woman created by Zeus, received many gifts—beauty, charm, wit, artistry, and lastly, curiosity. Included with the gifts was a box, which she was told never to open. But curiosity got the best of her. She lifted the lid, and out flew all the evils of the world, such as toil, illness, and despair. But at the bottom of the box lay Hope. Pandora’s last words were “Hope is what makes us strong. It is why we are here. It is what we fight with when all else is lost.” This story is the first thing which came to mind as I read over E Supremi, the first en- cyclical of our Patron Saint, St. Pius X. “In the midst of a progress in civilization which is justly extolled, who can avoid being appalled and afflicted when he beholds the greater part of mankind fighting among themselves so savagely as to make it seem as though strife were universal? The desire for peace is certainly harbored in every breast.” And the Pope goes on to explain that the peace of the godless is founded on sand. -

From Vatican II to Amoris Laetitia: the Catholic Social and Sexual Ethics Division and a Way of Ecclesial Interconnection

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Portal de Periódicos da UNICAP From Vatican II to Amoris Laetitia: The Catholic Social and Sexual Ethics Division and A Way of Ecclesial Interconnection Do Vaticano II a Amoris Laetitia: a divisão entre ética social e sexual católica e um novo caminho de interconexão eclesial Alexandre Andrade Martins Marquette University, EUA Abstract Keywords This paper navigates the development of ethical issues during Gaudium et Vatican II and the impulse to develop a new moral theology Spes. just after the Council. This paper argues, on one hand, that Amoris Laetitia, Gaudium et Spes develops a new moral theology based on the Catholic social imperative of conscience mediated by faith in issues of social teaching. ethics. On the other hand, the old moral orientation was Moral theology. preserved on sexual ethics. After the council, these two moral Conscience. faces have led magisterial teaching to two different paths that Social justice. can be seen chronologically in approaches used for issues of sexual ethics. social and sexual ethics. Vatican II encouraged a new moral theology, visible in social ethics in the years immediately following the Council. But the same spirit was not embraced by the Magisterium on issues of sexuality until the publication of Amoris Laetitia with its ecclesiology of pastoral discernment. Resumo Palavras-chave O artigo navega pelo desenvolvimento das questões éticas Gaudium et durante o Vaticano II e o impulso para o desenvolvimento de uma Spes. nova teologia moral imediatamente depois do Concílio. O texto Amoris argumenta, por um lado, que a Gaudium et Spes apresentou uma Laetitia. -

The Problem of Evil

THE PROBLEM OF EVIL: A NEW STUDY John Hick, lecturer in the philosophy of religion at Cambridge University, has written one of the most serious and important studies of the problem of evil to appear in English for a long time.1 It is a work both of historical interpretation and of systematic construction. While it is, under both aspects, not wholly invulnerable (what effort at reconciling evil and God ever is?), it is argued with such unusual persuasiveness and verve that it will force any serious reader to examine more critically his own theodicy touching the problem of evil. Prof. Hick suggests that the efforts of Christian thinkers to deal with the problem of evil and its origin can be categorized generically as Augustinian or Irenaean. He examines the former view in three main streams of tradition: (1) the Catholic one, as exemplified in Augustine himself, Hugh of St. Victor, Thomas Aquinas, and in a modern Thomist, Charles Journet; (2) the Cal- vinist tradition (Calvin and Karl Barth) ; (3) eighteenth-century optimism (Archbishop William King and Leibniz). Characteristic of this first effort to reconcile the existence of evil with an infinitely good God are the following points: the goodness of creation as the work of God; the privative character of evil; the origin of. sin and other evils in the free choice of angels and men constituted in an initial condition of innocence and perfection; the permission of evil by God with a view to effecting greater good; the principle of plenitude and the aesthetic conception of the perfection of the universe; a final dichotomy between the saved and the damned. -

The Mariology of Cardinal Journet

Marian Studies Volume 54 The Marian Dimension of Christian Article 5 Spirituality, III. The 19th and 20th Centuries 2003 The aM riology of Cardinal Journet (1891-1975) and its Influence on Some Marian Magisterial Statements Thomas Buffer Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/marian_studies Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Buffer, Thomas (2003) "The aM riology of Cardinal Journet (1891-1975) and its Influence on Some Marian Magisterial Statements," Marian Studies: Vol. 54, Article 5. Available at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/marian_studies/vol54/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Marian Library Publications at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marian Studies by an authorized editor of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Buffer: Mariology of Cardinal Journet THE MARIOLOGY OF CARDINALJOURNET (1891-1975) AND ITS INFLUENCE ON SOME MARIAN MAGISTERIAL STATEMENTS Thomas Buffer, S.T.D. * Charles Journet was born in 1891, just outside of Geneva. He died in 1975, having taught ftfty-six years at the Grande Seminaire in Fribourg. During that time he co-founded the journal Nova et Vetera, 1 became a personal friend of Jacques Maritain, 2 and gained fame as a theologian of the Church. In 1965, in recognition of his theological achievements, Pope Paul VI named him cardinal.3 As a theologian of the Church, Journet is best known for his monumental L'Eglise du Verbe Incarne (The Church of the Word Incarnate; hereafter EVI), 4 which Congar called the most profound ecclesiological work of the first half of the twentieth •Father Thomas Buffer is a member of the faculty of the Pontifical College ]osephinum (7625 N.