Book Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HEPTADIC VERBAL PATTERNS in the SOLOMON NARRATIVE of 1 KINGS 1–11 John A

HEPTADIC VERBAL PATTERNS IN THE SOLOMON NARRATIVE OF 1 KINGS 1–11 John A. Davies Summary The narrative in 1 Kings 1–11 makes use of the literary device of sevenfold lists of items and sevenfold recurrences of Hebrew words and phrases. These heptadic patterns may contribute to the cohesion and sense of completeness of both the constituent pericopes and the narrative as a whole, enhancing the readerly experience. They may also serve to reinforce the creational symbolism of the Solomon narrative and in particular that of the description of the temple and its dedication. 1. Introduction One of the features of Hebrew narrative that deserves closer attention is the use (consciously or subconsciously) of numeric patterning at various levels. In narratives, there is, for example, frequently a threefold sequence, the so-called ‘Rule of Three’1 (Samuel’s three divine calls: 1 Samuel 3:8; three pourings of water into Elijah’s altar trench: 1 Kings 18:34; three successive companies of troops sent to Elijah: 2 Kings 1:13), or tens (ten divine speech acts in Genesis 1; ten generations from Adam to Noah, and from Noah to Abram; ten toledot [‘family accounts’] in Genesis). One of the numbers long recognised as holding a particular fascination for the biblical writers (and in this they were not alone in the ancient world) is the number seven. Seven 1 Vladimir Propp, Morphology of the Folktale (rev. edn; Austin: University of Texas Press, 1968; tr. from Russian, 1928): 74; Christopher Booker, The Seven Basic Plots of Literature: Why We Tell Stories (London: Continuum, 2004): 229-35; Richard D. -

The New 'Ain Dara Temple: Closest Solomonic Parallel1

The New ‘Ain Dara Temple: Closest Solomonic Parallel1 By John Monson A stunning parallel to Solomon’s Temple has been discovered in northern Syria. The temple at ‘Ain Dara has far more in common with the Jerusalem Temple described in the Book of Kings than any other known building. Yet the newly excavated temple has received almost no attention in this country, at least partially because the impressive excavation report, published a decade ago, was written in German by a Syrian scholar and archaeologist. For centuries, readers of the Bible have tried to envision Solomon’s glorious Jerusalem Temple, dedicated to the Israelite God, Yahweh. Nothing of Solomon’s Temple remains today; the Babylonians destroyed it utterly in 586 B.C.E. And the vivid Biblical descriptions are of limited help in reconstructing the building: Simply too many architectural terms have lost their meaning over the ensuing centuries, and too many details are absent from the text. Slowly, however, archaeologists are beginning to fill in the gaps in our knowledge of Solomon’s building project. For years, pride of place went to the temple at Tell Ta‘yinat, also in northern Syria. When it was discovered in 1936, the Tell Ta‘yinat temple, unlike the ‘Ain Dara temple, caused a sensation because of its similarities to Solomon’s Temple. Yet the ‘Ain Dara temple is closer in time to Solomon’s Temple by about a century (it is, in fact, essentially contemporaneous), is much closer in size to Solomon’s Temple than the smaller Tell Ta‘yinat temple, has several features found in Solomon’s Temple but not in the Tell Ta‘yinat temple, and is far better preserved than the Tell Ta‘yinat temple. -

Bible Chronology of the Old Testament the Following Chronological List Is Adapted from the Chronological Bible

Old Testament Overview The Christian Bible is divided into two parts: the Old Testament and the New Testament. The word “testament” can also be translated as “covenant” or “relationship.” The Old Testament describes God’s covenant of law with the people of Israel. The New Testament describes God’s covenant of grace through Jesus Christ. When we accept Jesus as our Savior and Lord, we enter into a new relationship with God. Christians believe that ALL Scripture is “God-breathed.” God’s Word speaks to our lives, revealing God’s nature. The Lord desires to be in relationship with His people. By studying the Bible, we discover how to enter into right relationship with God. We also learn how Christians are called to live in God’s kingdom. The Old Testament is also called the Hebrew Bible. Jewish theologians use the Hebrew word “Tanakh.” The term describes the three divisions of the Old Testament: the Law (Torah), the Prophets (Nevi’im), and the Writings (Ketuvim). “Tanakh” is composed of the first letters of each section. The Law in Hebrew is “Torah” which literally means “teaching.” In the Greek language, it is known as the Pentateuch. It comprises the first five books of the Old Testament: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy. This section contains the stories of Creation, the patriarchs and matriarchs, the exodus from Egypt, and the giving of God’s Law, including the Ten Commandments. The Prophets cover Israel’s history from the time the Jews entered the Promised Land of Israel until the Babylonian captivity of Judah. -

The Building of the First Temple

Forschungen zum Alten Testament Herausgegeben von Konrad Schmid (Zürich) · Mark S. Smith (New York) Hermann Spieckermann (Göttingen) 103 Peter Dubovsky´ The Building of the First Temple A Study in Redactional, Text-Critical and Historical Perspective Mohr Siebeck Peter Dubovsky´, born 1965; 1999 SSL; 2005 ThD; currently dean at the Pontifical Biblical Institute in Rome and professor of the Old Testament and history. ISBN 978-3-16-153837-7 ISSN 0940-4155 (Forschungen zum Alten Testament) Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbiblio- graphie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2015 by Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen, Germany. www.mohr.de This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permitted by copyright law) without the publisher’s written permission. This applies particularly to reproductions, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic systems. The book was printed by Gulde Druck in Tübingen on non-aging paper and bound by Buchbinderei Spinner in Ottersweier. Printed in Germany. To my friend John W. O’Malley Preface The project that led to this book started in 2008 when I was preparing a course on 1 Kings 1–11 at the Pontifical Biblical Institute. It was completed thanks to a generous grant from Georgetown University, which offered me a Jesuit Chair (2014). This book would not have been possible without the constant support of my fellow Jesuits, my colleagues at the Pontifical Biblical Institute, and -

Menorah I. Hebrew Bible/Old Testament II. Judaism

645 Menorah 646 tory of the Anabaptists and the Mennonites (Scottdale, Pa. 1993). cal Jewish interpretation of the Exodus texts, which ■ Loewen R./C. Snyder, Seeking Places of Peace: Global Mennonite present contradictory information about the num- History Series: North America (Intercourse, Pa. 2012). ■ Valla- ber and shape of the lamps. The menorah was dares, J. P., Mission and Migration: Global Mennonite History among the objects taken from the temple by Antio- Series: Latin America (Intercourse, Pa. 2010). chus Epiphanes in 167 BCE (1 Macc 1:21; Josephus Derek Cooper Ant. 12.250). Whereas 1 Macc used the singular See also / Anabaptists; / Hutterites; / Ley- form, Josephus mentions that menorot were re- den, Jan van; / Reformation moved. The Maccabean restoration of the temple in- cluded an improvised menorah of iron rods overlaid with tin (bMen 28b). That these rods numbered Menorah seven (MegTa 9) is the first mention of a seven- branched menorah in the Hasmonean period I. Hebrew Bible/Old Testament (Hachlili: 22). After Judas Maccabeus purified the II. Judaism III. Christianity temple in 165 BCE, new sacred objects were made IV. Visual Arts for it including a menorah (1 Macc 4:49). This men- orah apparently had seven branches because multi- I. Hebrew Bible/Old Testament ple lamps were lit on the menorah to provide light for the temple (v. 50). In 39 BCE the menorah The Hebrew word me˘nôrâ (LXX λυχνία) refers gener- paired with the table of showbread appeared on a ally to a lampstand whose function was to light a lepton coin issued by Mattathias Antigonos (40–37 room (2 Kgs 4:10). -

316 Chronology: Timeline of Biblical World History Biblestudying.Net

Chronology 316: Timeline of Biblical World History biblestudying.net Brian K. McPherson and Scott McPherson Copyright 2012 Period Two: From the Birth of Isaac to the Exodus In this section of our study we will present the scriptural data that is relevant to calculating the amount of time from the birth of Isaac to the Israelite Exodus from Egypt. Although it is necessary to do some cross-referencing and comparison of scriptural texts, our discussion of this time period will be simpler than our examination of factors related to the prior period. We will start with Genesis 15:13-16. In Genesis 15:13-16, God tells Abraham that his descendents will be servants in a land that is not their own (Egypt) for 400 years and that they will come out in the fourth generation. Genesis 15:13 And he said unto Abram, Know of a surety that thy seed shall be a stranger in a land that is not theirs, and shall serve them; and they shall afflict them four hundred years; 14 And also that nation, whom they shall serve, will I judge: and afterward shall they come out with great substance. 15 And thou shalt go to thy fathers in peace; thou shalt be buried in a good old age. 16 But in the fourth generation they shall come hither again: for the iniquity of the Amorites is not yet full. This passage provides the basic data to begin our understanding of the duration of time from Isaac’s birth to the Exodus. From this passage we learn several things. -

King Solomon's Fall

King Solomon’s Fall 1 KINGS 11:1-13 Baxter T. Exum (#1482) Four Lakes Church of Christ Madison, Wisconsin January 6, 2019 David Petraeus. Most of us recognize this man as one of the most well known, most successful, and most highly decorated and respected soldiers in the history of this nation. Having graduated in the top 5% of his class at West Point, he went on to serve 37 years in the United States Army. During that time, he continued to earn masters and PhD degrees and to serve as an assistant professor at the United States Military Academy. In many ways, his many accomplishments exceed my ability to explain them. We know that he served as Commander of the United States Central Command, which oversees military efforts in the Middle East. We know that he developed what is now known as the Petraeus Doctrine, a comprehensive plan for overcoming the kind of insurgency that we’ve seen in Iraq and Afghanistan. We also know that in 2011 Petraeus was nominated by President Obama to serve as Director of the CIA and was confirmed in the senate by an unheard-of unanimous vote of 94-0, reflecting the tremendous respect that this man had earned over a long and distinguished career. However, we also know what happened next. In November 2012, after an FBI investigation, Petraeus resigned as head of the CIA, amid allegations of an extramarital affair and that he shared classified information with his official biographer, Paula Broadwell. This is a smart, courageous, respected, and highly educated man, and yet near the end of his life he apparently made some terribly unwise decisions. -

Editorial Theory and the Range of Translations for 'Cedars of Lebanon

HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies ISSN: (Online) 2072-8050, (Print) 0259-9422 Page 1 of 12 Original Research Editorial theory and the range of translations for ‘cedars of Lebanon’ in the Septuagint cedar] is translated in the majority of cases as] אֶ רֶ ז Authors: Although the Hebrew source text term 1 Cynthia L. Miller-Naudé κέδρος [cedar] or its adjective κέδρινος in the Septuagint, there are cases where the following Jacobus A. Naudé1 translations and strategies are used: (1) κυπάρισσος [cypress] or the related adjective Affiliations: κυπαρίσσινος, (2) ξύλον [wood, tree] and (3) non-translation and deletion of the source text 1Department of Hebrew, item. This article focuses on these range of translations. Using a complexity theoretical University of the Free State, approach in the context of editorial theory (the new science of exploring texts in their South Africa manuscript contexts), this article seeks to provide explanations for the various translation Corresponding author: choices (other than κέδρος and κέδρινος). It further aims to determine which cultural values of Cynthia Miller-Naudé, the translators have influenced those choices and how they shape the metaphorical and [email protected] symbolic meaning of plants as determined by Biblical Plant Hermeneutics, which has placed Dates: the taxonomy of flora on a strong ethnological and ethnobotanical basis. Received: 30 Apr. 2018 Accepted: 21 June 2018 Published: 01 Nov. 2018 Introduction cedar] is translated in the] אֶ רֶ ז How to cite this article: As shown in Naudé and Miller-Naudé (2018), the Hebrew term Miller-Naudé, C.L. & Naudé, Septuagint as κέδρος [cedar] or with the adjectival form κέδρινος in 65 cases. -

Solomon's Dedication Prayer

Solomon’s Dedication Prayer Bible Background • 1 KINGS 8:22–53; 2 CHRONICLES 6:12–42 Printed Text • 1 KINGS 8:22–30, 52–53 | Devotional Reading • 1 TIMOTHY 2:1–6 Aim for Change By the end of the lesson, we will: ANALYZE the importance of a national temple for Israel, EXPRESS gratitude for God’s faithfulness in covenant relationships, and EMBRACE a worshipful lifestyle in light of God’s continuing goodness. In Focus Claudine and her husband, Gus, moved to Miami, Florida, after they both retired from the Ohio State Police Department. The winter season in Ohio was harsh. They desired to live in a warmer climate. They liked the weather and the people they met. But there was one aspect of living in Miami they disliked. They could not find a church similar to home. One day Brian, their next-door neighbor, invited Gus and Claudine to join him and his wife at church on Sunday. Gus hesitated in responding because Brian attended a nondenominational church. Gus had to convince his wife to go with him. “It will not hurt to just go this one time. I know they are of a different race and worship experience. Maybe it will be a good experience.” Claudine reluctantly went. They attended the 8:00 a.m. worship service with Brian and his wife. When they entered the sanctuary, the praise and worship team was leading the congregation in songs. There were multigenerational families of different nationalities in attendance. After a few minutes, Claudine whispered to Gus, “I feel God’s presence in this place.” The pastor’s sermon inspired them to make a commitment to return for another visit. -

Teacher Bible Study Lesson Overview

4th-6th Grade Kids Bible Study Guide Unit 12, Session 2: Solomon Built the Temple TEACHER BIBLE STUDY When David was king, he wanted to build a temple for God, but God did not allow him to. “When your time comes and you rest with your fathers, I will raise up after you your descendant, who will come from your body, and I will establish his kingdom. He will build a house for My name, and I will establish the throne of his kingdom forever” (2 Samuel 7:12-13). God said King David’s son would build the temple. King Solomon began to gather materials to build the temple. He ordered cedar and cypress timbers from Lebanon. He gathered 30,000 men from all of Israel as laborers to excavate stone and prepare the timbers for the temple’s construction. The temple was impressive. The entire interior was cedar. King Solomon had everything covered with gold. In all, it took seven years for the temple to be completed. Inside the temple was furniture and accessories. (See 1 Kings 7:48-50.) It came time to dedicate the temple. All of the Israelites gathered in Jerusalem. The priests brought the ark of the Lord to the most holy place, and a cloud filled the house of the Lord. God’s glory filled the temple. Solomon prayed to God. He praised God for keeping His covenant with David. Solomon recognized that God is not confined to a temple. “Even heaven, the highest heaven, cannot contain You, much less this temple I have built” (1 Kings 8:27). -

1 Kings 6:1-38 “IN My Father's House”

1 Kings 6:1-38 “IN My Father’s House” Luke 19:41 Now as He drew near, He saw the city and wept over it, 1 Kings 6.1-38 1 • Josephus writes concerning the Temple in Jesus day: “The exterior of the building wanted nothing that could astound either mind or eye. For, being covered on all sides with massive plates of gold, the sun was no sooner up than it radiated so fiery a flash that persons straining to look at it were compelled to avert their eyes, as from the solar rays. To approaching strangers it appeared from a distance like a snow-clad mountain; for all that was not overlaid with gold was of purest white. Some of the stones in the building were forty-five cubits in length, five in height and six in breadth.” (War, V.5.6) Zechariah 12:2 “Behold, I will make Jerusalem a cup of drunkenness to all the surrounding peoples, when they lay siege against Judah and Jerusalem. Zechariah 12:10-12 10 “And I will pour on the house of David and on the inhabitants of Jerusalem the Spirit of grace and supplication; then they will look on Me whom they pierced. Yes, they will mourn for Him as one mourns for his only son, and grieve for Him as one grieves for a firstborn. 11 In that day there shall be a great mourning in Jerusalem, like the mourning at Hadad Rimmon in the plain of Megiddo. 12 And the land shall mourn, every family by itself . -

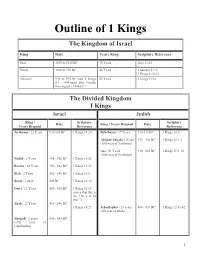

Outline of 1 Kings

Outline of 1 Kings The Kingdom of Israel King Date Years King Scripture Reference Saul 1050 to 1010 BC 40 Years Acts 13:21 David 1010 to 970 BC 40 Years 2 Samuel 5:1-5 1 Kings 2:10-12 Solomon 970 to 930 BC (see 1 Kings 40 Years 1 Kings 11:42 6:1 ~ 476 years after Exodus from Egypt - 1446 BC) The Divided Kingdom I Kings Israel Judah King / Scripture Scripture Date King / Years Reigned Date Years Reigned Reference Reference Jeroboam / 22 Years 930-908 BC 1 Kings 14:20 Rehoboam / 17 Years 930-913 BC 1 Kings 14:21 Abijam (Abijah )/3 Years 913 - 910 BC 1 Kings 15:1-2 (18th year of Jeroboam) Asa / 41 Years 910 - 869 BC 1 Kings 15:9-10 (20th year of Jeroboam) Nadab / 2 Years 908 - 906 BC 1 Kings 15:25 Baasha / 24 Years 906 - 882 BC 1 Kings 15:33 Elah / 2 Years 882 - 880 BC 1 Kings 16:8 Zimri / 7 days 880 BC 1 Kings 16:15 Omri / 12 Years 880 - 868 BC 1 Kings 16:23 (states that this is the 31st year of Asa??) Ahab / 22 Years 868 - 846 BC 1 Kings 16:29 Jehoshaphat / 25 years 864 - 839 BC 1 Kings 22:41-42 (4th year of Ahab) Ahaziah / 2 years 846 - 844 BC (17th year of Jehoshaphat) 1 Introduction to 1 Kings The author of 1 Kings is unknown. Whoever this inspired writer was he must have lived and wrote during the days of Judah's Babylonian captivity due to the book ending during these days.