The Crystal Chemistry, Dissolution Kinetics and Dehydroxylation of Oxide-Type Lateritic Ni Ore

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alkali Pyroxenes and Amphiboles: a Window on Rare

Alkali pyroxenes and amphiboles: a window on rare earth elements and other high field strength elements behavior through the magmatic-hydrothermal transition of peralkaline granitic systems Cyrielle Bernard, Guillaume Estrade, Stefano Salvi, Didier Béziat, Martin Smith To cite this version: Cyrielle Bernard, Guillaume Estrade, Stefano Salvi, Didier Béziat, Martin Smith. Alkali pyroxenes and amphiboles: a window on rare earth elements and other high field strength elements behavior through the magmatic-hydrothermal transition of peralkaline granitic systems. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, Springer Verlag, 2020, 10.1007/s00410-020-01723-y. hal-02989854 HAL Id: hal-02989854 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02989854 Submitted on 5 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 1 Alkali pyroxenes and amphiboles: a window on Rare Earth Elements and other High Field Strength 2 Elements behavior through the magmatic-hydrothermal transition of peralkaline granitic systems 3 4 Cyrielle Bernarda, Guillaume Estradea⸸, Stefano Salvia, Didier Béziata , Martin Smithb 5 a GET, CNRS, UPS, Université de Toulouse III, Toulouse, France 6 b School of Environment and Technology, University of Brighton, Brighton, BN2 4GJ, UK 7 8 ⸸ Corresponding author: [email protected] 9 ORCID: 0000-0001-6907-7469 10 11 12 Acknowledgments 13 This work was supported by an INSU/TelluS grant from CNRS (French National Center for Scientific 14 Research). -

Coupled Substitution of H and Minor Elements in Rutile and The

American Mineralogist, Volume 78, pages I 181-1I9I, 1993 Coupled substitution of H and minor elementsin rutile and the implications of high OH contentsin Nb- and Cr-rich rutile from the upper mantle DrvrrrnrosVr-lssopour,os S. S. Papadopulosand Associates,Inc.,7944 Wisconsin Avenue, Bethesda,Maryland 20814-3620,U.S.A. Gponcn R. Rossnn.q,N Division of Geological and Planetary Sciences,California Institute of Technology,Pasadena, California 91125, U.S.A. SrnpHrN E. Hlccrnry Department of Geology, University of Massachusetts,Amherst, Massachusetts01003, U.S.A. Ansrucr Infrared absorption spectraof rutile crystals from a variety of geologicalenvironments (carbonatite,hydrothermal vein, kyanite * rutile + lazulite association,xenoliths that are kimberlite hosted and dominated by Nb- and Cr-rich rutile) exhibit strong absorption in the 3300-cm-' regtrondue to interstitial protons bonded to structure O. In general the proton is located at sites slightly displaced from t/zYz0of the unit cell, although some samplesshow evidenceofadditional protons at tetrahedral interstitial sites.H contents of rutile range up to 0.8 rvto/oHrO, the highest concentrations occurring in mantle-derived Nb- and Cr-rich rutile of metasomatic origin. The role of H in rutile was examined, particularly with respect to its relations to other impurities. Protons are present in the rutile structure to compensatefor trivalent substitutional cations (Cr, Fe, V, Al), which are only partly compensatedby pentavalent ions (Nb, Ta). The possibility of using the H content of rutile as a geohygrometeris illustrated for the caseof coexisting hematite and rutile. INrnonucrroN crystalsto an OH stretch mode. The study by von Hippel (1962) pro- Rutile is known to have a greal affinity for H, and et al. -

The Geochemistry of Gold-Bearing and Gold-Free Pyrite and Marcasite from the Getchell Gold Deposit, Humboldt County, Nevada

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-2001 The geochemistry of gold-bearing and gold-free pyrite and marcasite from the Getchell gold deposit, Humboldt County, Nevada Kelli Diane Weaver University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Weaver, Kelli Diane, "The geochemistry of gold-bearing and gold-free pyrite and marcasite from the Getchell gold deposit, Humboldt County, Nevada" (2001). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 1344. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/rwv9-1zgy This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UM! films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. -

Stability and Solid Solutions of Hydrous Alumino-Silicates in the Earth’S Mantle

minerals Article Stability and Solid Solutions of Hydrous Alumino-Silicates in the Earth’s Mantle Wendy R. Panero 1,* and Razvan Caracas 2,3 1 School of Earth Sciences, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210, USA 2 CNRS, Laboratoire de Geologie de Lyon, Ecole Normale Supérieure de Lyon, 69364 Lyon, France; [email protected] 3 The Centre for Earth Evolution and Dynamics (CEED), University of Oslo, Postbox 1028 Blindern, N-0315 Oslo, Norway * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 14 February 2020; Accepted: 28 March 2020; Published: 8 April 2020 Abstract: The degree to which the Earth’s mantle stores and cycles water in excess of the storage capacity of nominally anhydrous minerals is dependent upon the stability of hydrous phases under mantle-relevant pressures, temperatures, and compositions. Two hydrous phases, phase D and phase H, are stable to the pressures and temperatures of the Earth’s lower mantle, suggesting that the Earth’s lower mantle may participate in the cycling of water. We build on our prior work of density functional theory calculations on phase H with the stability, structure, and bonding of hydrous phases D, and we predict the aluminum partitioning with H in the Al2O3-SiO2-MgO-H2O system. We address the solid solutions through a statistical sampling of site occupancy and calculation of the partition function from the grand canonical ensemble. We show that each phase has a wide solid solution series between MgSi2O6H2-Al2SiO6H2 and MgSiO4H2-2dAlOOH + SiO2, in which phase H is more aluminum rich than phase D at a given bulk composition. -

Redalyc.CATION SUBSTITUTIONS GOVERNING the CHEMISTRY OF

Boletín de Geología ISSN: 0120-0283 [email protected] Universidad Industrial de Santander Colombia Ríos, C.A. CATION SUBSTITUTIONS GOVERNING THE CHEMISTRY OF AMPHIBOLE IN THE SILGARÁ FORMATION METABASITES AT THE SOUTHWESTERN SANTANDER MASSIF Boletín de Geología, vol. 27, núm. 2, julio-diciembre, 2005, pp. 13-30 Universidad Industrial de Santander Bucaramanga, Colombia Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=349631990001 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Boletín de Geología Vol. 27, No. 2, julio-diciembre de 2005 CATION SUBSTITUTIONS GOVERNING THE CHEMISTRY OF AMPHIBOLE IN THE SILGARÁ FORMATION METABASITES AT THE SOUTHWESTERN SANTANDER MASSIF Ríos, C.A.1 ABSTRACT Amphibole-bearing parageneses from the Silgará Formation metabasites at the southwestern Santander Massif record evidence of prograding metamorphism. Optical and microprobe analyses, together with thermobarometric estimates on IV these rocks, show that the main variation in Ca-amphibole is the simultaneous substitution of Al into the T1 site (Al ) IV and Na+K into the A-site of the amphibole’s crystal structure. Al is strongly temperature dependant, and this dependancy masks any pressure effect. Changes in the chemical composition of Ca-amphibole grains are interpreted through coupled substitutions, and reactions with co-existing minerals during an increase in metamorphic conditions from greenschist to lower amphibolite facies, being favourable circumstances record not only the metamorphic facies reached by rocks but also the P-T conditions by which these were attained. -

Joint Meeting

Joint Meeting 19. Jahrestagung der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Kristallographie 89. Jahrestagung der Deutschen Mineralogischen Gesellschaft Jahrestagung der Österreichischen Mineralogischen Gesellschaft (MinPet 2011) 20.-24. September 2011 Salzburg Referate Oldenbourg Verlag – München Inhaltsverzeichnis Plenarvorträge ............................................................................................................................................................ 1 Goldschmidt Lecture .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Vorträge MS 1: Crystallography at High Pressure/Temperature ................................................................................................. 4 MS 2: Functional Materials I ........................................................................................................................................ 7 MS 3: Metamorphic and Magmatic Processes I ......................................................................................................... 11 MS 4: Computational Crystallography ....................................................................................................................... 14 MS 5: Synchrotron- and Neutron Diffraction ............................................................................................................. 17 MS 6: Functional Materials II and Ionic Conductors ................................................................................................ -

Synthetic Hypersilicic Cl-Bearing Mica in the Phlogopite-Celadonite

American Mineralogist, Volume 93, pages 1429-1436, 2008 Synthetic hypersilicic Cl-bearing mica in the phlogopite-celadonite join: A multimethodical characterization of the missing link between di- and tri-octahedral micas at high pressures SABRINA NAZZARENI,!'* PAOLA COMODI,! LUCA BINDI,2 OLEG G. SAFONOV,3 YURIY A. LITVIN,3 AND LEONID L. PERCHUK3,4 'Department of Earth Sciences, University ofPerugia, Perugia, Italy 'Museo di Storia Naturale, Sezione di Mineralogia, Universita di Firenze, Via La Pira 4, 1-50121, Firenze, Italy 3Institute of Experimental Mineralogy, Chemogolovka, Moscow, Russia "Department of Petrology, Moscow State University, Moscow, Russia ABSTRACT A hypersilicic Cl-bearing mica was synthesized at 4 GPa and 1200-1250 °C, close to the solidus of the join diopside-jadeite-KCl, in association with diopside-jadeite pyroxene, K-rich alumino silicate glass and/or sanidine and (K,Na)Cl. The mica shows a negative correlation between tetrahedral Si and octahedral (AI + Mg), suggesting an Al-celadonitic substitution (Si + VIAl+ VIO = IVAI+ VIMg) and a chemical formula: Kl01(Mg245AlolDo35h~lSi352Alo48h~401O[(OH,0)166Clo34)h~2' The presence of hydroxyl was confirmed by OH stretching modes at 3734 and 3606 cm' in the Raman spectra. Single- crystal X-ray diffraction data provide the unit-cell parameters (space group C2/m, 1M polytype): a = 5.299(4), b = 9.167(3), C = 10.226(3) A, ~ =100.06(4)°, V= 489.1(4) N. The structure refinement shows the presence of vacancies on the octahedral sites (15% for Ml and 6.5% for M2). Chlorine occupies a position about 0.5 A from 04 with partial occupancy (0.39 apfu). -

VARIATION in Mn/Fe SYSTEMATICS in PYROXENE from the MOON: the EFFECTS of CONTRASTING Ti and Al ACTIVITIES

50th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference 2019 (LPI Contrib. No. 2132) 1413.pdf VARIATION IN Mn/Fe SYSTEMATICS IN PYROXENE FROM THE MOON: THE EFFECTS OF CONTRASTING Ti AND Al ACTIVITIES. J. J. Papike, S. B. Simon, and C. K. Shearer. Institute of Meteoritics, Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, New Mexico 87131, U.S.A. ([email protected]). Introduction: Papike et al. [1] introduced a tech- components are very small. Coupled substitutions are nique where the Mn/Fe ratios of olivine or pyroxene required to incorporate trivalent cations and Ti4+ into and the anorthite content of plagioclase provided a tool the pyroxene crystal structure because they replace to identify the planetary parentage of newly discovered divalent Mg and Fe in the M1 site [7], thus creating an meteorites. A recent paper [2] refined this technique, excess charge of +1 or +2, respectively. Crystal charge focusing on the angrite meteorites, and a new, robust balance must be maintained, and and balancing of determinative curve was obtained. On a plot of Mn vs. charge excesses can be accomplished by simultaneous- Fe cations per formula unit for pyroxene from basalts, ly substituting: 1) one Al cation into the tetrahedral site the slopes of the data trends decrease in the sequence for Si; or 2) one Na cation into the M2 site for Ca, per Vesta, Mars, Earth, and Moon. Analyses of angrite unit of excess charge. Although pyroxenes from the pyroxenes are not directly comparable to those from three mare basalt groups exhibit a range of Mn/Fe rati- the other bodies because in angrite pyroxenes the M2 os, the positioning of an individual point on a plot of sites are completely filled by Ca [e.g., 3] and therefore Mn vs. -

Trace-Element Systematics of Pyrite and Its Implications for Refractory

J. Earth Syst. Sci. (2019) 128 233 Ó Indian Academy of Sciences https://doi.org/10.1007/s12040-019-1256-9 (0123456789().,-volV)(0123456789().,-volV) Trace-element systematics of pyrite and its implications for refractory gold mineralisation within the carbonaceous metasedimentary units of Palaeoproterozoic South Purulia shear zone, eastern India SUBHASHREE MAJUMDAR,SAHENDRA SINGH* ,PRABODHA RANJAN SAHOO and A S VENKATESH Department of Applied Geology, Indian Institute of Technology (Indian School of Mines), Dhanbad 826 004, India. *Corresponding author. e-mail: [email protected] MS received 10 January 2018; revised 10 June 2019; accepted 13 June 2019 Globally, refractory gold occurs in significant proportions in many types of gold deposits. The present work reports the occurrence of sulphide-hosted refractory gold within the carbonaceous phyllites of the South Purulia shear zone in the Singhbhum crustal province, eastern India. Detailed textural charac- teristics, paragenesis and trace-element concentrations of different generations of pyrites were studied to understand their evolutionary stages and the mechanism of gold incorporation in pyrites. Four types of pyrites, which are closely associated with gold mineralisation were identified in the host rock, i.e., car- bonaceous phyllite. Py I is of diagenetic origin, whereas Py II, Py III and Py IV are of hydrothermal origin. Laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry studies confirm the presence of invisible/refractory gold concentration up to 110.55 ppm within these pyrites. The positive correlation between Au and As in pyrite indicates the significant role of As in the incorporation of gold in pyrite. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy confirms the presence of organic matter that provided suit- able redox conditions for the precipitation of auriferous pyrites. -

Chapter 5: Lunar Minerals

5 LUNAR MINERALS James Papike, Lawrence Taylor, and Steven Simon The lunar rocks described in the next chapter are resources from lunar materials. For terrestrial unique to the Moon. Their special characteristics— resources, mechanical separation without further especially the complete lack of water, the common processing is rarely adequate to concentrate a presence of metallic iron, and the ratios of certain potential resource to high value (placer gold deposits trace chemical elements—make it easy to distinguish are a well-known exception). However, such them from terrestrial rocks. However, the minerals separation is an essential initial step in concentrating that make up lunar rocks are (with a few notable many economic materials and, as described later exceptions) minerals that are also found on Earth. (Chapter 11), mechanical separation could be Both lunar and terrestrial rocks are made up of important in obtaining lunar resources as well. minerals. A mineral is defined as a solid chemical A mineral may have a specific, virtually unvarying compound that (1) occurs naturally; (2) has a definite composition (e.g., quartz, SiO2), or the composition chemical composition that varies either not at all or may vary in a regular manner between two or more within a specific range; (3) has a definite ordered endmember components. Most lunar and terrestrial arrangement of atoms; and (4) can be mechanically minerals are of the latter type. An example is olivine, a separated from the other minerals in the rock. Glasses mineral whose composition varies between the are solids that may have compositions similar to compounds Mg2SiO4 and Fe2SiO4. -

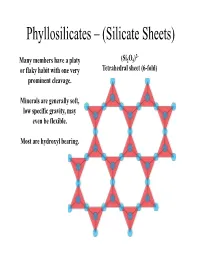

Phyllosilicates – (Silicate Sheets)

Phyllosilicates – (Silicate Sheets) 2- Many members have a platy (Si2O5) or flaky habit with one very Tetrahedral sheet (6-fold) prominent cleavage . Minerals are generally soft, low specific gravity, may even be flexible. Most are hydroxyl bearing. Each tetrahedra is bound to three neiggghboring tetrahedra via three basal bridging oxygens. The apical oxygen of each tetrahedral in a sheet all point in the same direction. The sheets are stacked either apice-to- apice or base-to-base. In an undistorted sheet the hydroxyl (OH) group sits in the centre and each outlined triangle is equivalent. Sheets within sheets…. Apical oxygens, plus the –OH group, coordinate a 6-fold (octahedral) site (XO6). These octahedral sites form infinitely extending sheets. All the octahedra lie on triangular faces, oblique to the tetrahedral sheets. The most common elements found in the 6 -fold site are Mg (or Fe) or Al . Dioctahedral vs Trioctahedral Mg and Al have different charges, but the sheet must remain charge neutral . With 6 coordinating oxygens, we have a partial charge of -6. How many Mg2+ ions are required to retain neutrality? How many Al3+ ions are required to retain neutrality? Mg occupies all octahedral sites, while Al will only occupy 2 out of every 3. The stacking of the sheets dictates the crystallography and c hem istry o f eac h o f t he p hhyll llosili cates. Trioctahedral Dioctahedral O Brucite Gibbsite Hydroxyl Magnesium Aluminium Trioctahedral Is this structure charge neutral? T O T Interlayer Cation T O T Potassium (K+) Phlogopite (Mg end-member biotite) Dioctahedral Is this structure charge neutral? T O T Interlayer Cation T O T Potassium (K+) Muscovite Compositional variation in phyllosilicates There is little solid solution between members of the dioctahedral and trioctahedral groups. -

Tungsten-Bearing Rutile from the Kori Kollo Gold Mine, Bolivia

Mineralogical Magazine, June 1998, Vol. 62(3), pp. 421-429 Tungsten-bearing rutile from the Kori Kollo gold mine, Bolivia C. M. R~CE, K. E. DARKE, J. W. STILL Department of Geology and Petroleum Geology, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen, Scotland AND E. E. LACHOWSKI Department of Chemistry, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen, Scotland ABSTRACT W-bearing rutile formed during alteration ofjarosite by resurgent hydrothermal fluids in the oxide zone of the Kori Kollo gold deposit. The futile shows sector zoning in basal sections and well developed multiple growth zones, both defined in backscatter electron images by variations in the W content. The maximum WO3 content is 5.3 wt.% and W substitutes for Ti with double substitution of Fe to maintain charge balance. The causes of multiple growth bands are considered to be changes in externally controlled variables occurring in a shallow hydrothermal system. Whereas Ti is probably leached from biotite in dacitic rocks, the W is introduced by hydrothermal fluids. KEYWORDS-" tungsten, rutile, jarosite, gold deposits, Bolivia. Introduction Geological setting TUNGSTEN-BEARING futile is a rare occurrence. Kori Kollo is the largest gold mine in Bolivia, and Standard mineral reference texts discuss the is a precious-metal-rich variety of the polyme- common substitution of Fe, Nb, A1, Ta, Sn and tallic vein deposits characteristic of the Bolivian Cr into the rutile structure, but there is no Altiplano (Ludington et al., 1992). It is located reference to tungsten. The first mention of W in within one of a cluster of altered dacitic stocks of rutile was at Big Bell, Western Australia, where it Miocene age in the La Joya District 40 km west of occurs in mica schist and pegmatite.