South African Defence Industry Strategy 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Which Is the Largest Manufacturer of Defence Equipment in South Africa and Operates in the Military Aerospace and Landward Defence Environment

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY DENEL Denel is a state-owned company (SOC), which is the largest manufacturer of defence equipment in South Africa and operates in the military aerospace and landward defence environment. Denel is an important defence contractor in the domestic market and a key supplier to the South African National Defence Force (SANDF) both as original equipment manufacturer (OEM) and for the overhaul, maintenance, repair, refurbishment and upgrade of equipment in the SANDF’s arsenal. Denel reports to the Minister of Public Enterprises who appoints an independent board of directors to oversee an executive management team, managing the day-to-day operations. The executive management team also manages several business divisions and associated companies, including Denel Aeronautics, Denel Maritime, Pretoria Metal Pressings, Denel Dynamics, Denel Land Systems, Denel Vehicle Systems (Pty) Ltd and Denel Aerostructures SOC Ltd. With the release of the #Guptaleaks in May 2017, the actions and good governance of the board of directors were brought into question, not only because of the Denel-Asia deal, but also because of the relationships between key decision makers and the Gupta family. OUTA explores the capturing of Denel in this submission and provides supporting evidence. Before July 2015, Denel was led by a board of directors chaired by Riaz Saloojee. This board’s direction resulted in a series of profitable years as set out in the second issue of a 2015 Denel- issued communique. Denel had good prospects for its future and an order book of more than R35 billion and the group CFO Fikile Mhlonto was nominated as Public CFO of the year. -

Department of Public Enterprises Strategic Plan Presentation

PRESENTATION TO THE SELECT COMMITTEE 23rd March 2011 STRATEGIC PLAN 2011-2014 CONFIDENTIAL Contents • Evolution of the DPE • DPE : - Shareholder Management and Oversight - Mission • Economic challenges facing South Africa • Role of SOE in driving investments • DPE’s Plan of Action in responding to the New Growth Path • Performance against current year (2010/11) Strategic Plan • Strategic Plan 2011/14 : purposes, priorities and budgets • SOE : Contributions and Impact • Annexures : 2011/12 project outputs, measures and targets. CONFIDENTIAL 2 Evolution of DPE’s strategic mandate • 1994 ‒ 1998: Established as the office of privatisation focused on disposal of SOE. • 1998 ‒ 2003: Emphasise shifts to restructuring of SOE with focus on equity partnerships, initial public offerings and concessioning of specific assets to optimise shareholder value and economic efficiency. • Post 2003: Develop the SOE as focused sustainable state owned business entities delivering on a specific strategic economic mandate. Direct SOE to align strategy with the needs and policy direction of the domestic economy, namely: • Positioning or entry of SOE in pursuit of industry or sectoral policies • The development & promotion of policies by DPE that enhance operation of SOE. Post 2003, the DPE has managed the portfolio of SOE towards the achievement of the following long term objectives: CONFIDENTIAL 3 The DPE’s mission is to ensure that the SOE are both financially sustainable and deliver on government’s developmental objectives To optimize the alignment between the role of the SOE in the national economic strategy and the performance of the DPE’s portfolio of enterprises through delivering best practice shareholder management services and engaging with stakeholders to create an enabling environment for such alignment. -

South Africa's Defence Industry: a Template for Middle Powers?

UNIVERSITYOFVIRGINIALIBRARY X006 128285 trategic & Defence Studies Centre WORKING PAPER NO. 358 South Africa's Defence Industry: A Template for Middle Powers? Greg Mills and Martin Edmonds AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY University of Virginia Libraries SDSC Working Papers Series Editor: Helen Hookey Published and distributed by: Strategic and Defence Studies Centre The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200 Australia Tel: 02 62438555 Fax: 02 624808 16 WORKING PAPER NO. 358 South Africa's Defence Industry: A Template for Middle Powers? Greg Mills and Martin Edmonds National Library of Australia Cataloguirtg-in-Publication entry Mills, Greg. South Africa's defence industry : a template for middle powers? ISBN 0 7315 5409 4. 1. Weapons industry - South Africa. 2. South Africa - Defenses. I. Edmonds, Martin, 1939- . II. Australian National University. Strategic and Defence Studies Centre. III. Title. 338.4735580968 AL.D U W^7 no. 1$8 AUTHORS Dr Greg Mills and Dr Martin Edmonds are respectively the National Director of the South African Institute of Interna tional Affairs (SAIIA) based at Wits University, Johannesburg, South Africa, and Director: Centre for Defence and Interna tional Security Studies, Lancaster University in the UK. South Africa's Defence Industry: A Template for Middle Powers? 1 Greg Mills and Martin Edmonds Introduction The South African arms industry employs today around half of its peak of 120,000 in the 1980s. A number of major South African defence producers have been bought out by Western-based companies, while a pending priva tisation process could see the sale of the 'Big Five'2 of the South African industry. This much might be expected of a sector that has its contemporary origins in the apartheid period of enforced isolation and self-sufficiency. -

The United States Arms Embargo Against South Africa: an Analysis of the Laws, Regulations, and Loopholes

Comment The United States Arms Embargo Against South Africa: An Analysis of the Laws, Regulations, and Loopholes Raymond Paretzkyt Introduction With reports of violence and unrest in the Republic of South Africa a daily feature in American newspapers, public attention in the United States has increasingly focused on a variety of American efforts to bring an end to apartheid.. Little discussed in the ongoing debate over imposi- tion of new measures is the sanction that the United States has main- tained for the past twenty-three years: the South African arms embargo. How effective has this sanction been in denying South Africa access to items with military utility? Are there ways to strengthen the arms em- bargo so that it achieves greater success? An evaluation of the embargo is complicated by the fact that there is no one place in which the laws implementing it can be found. Rather, the relevant regulations have been incorporated into the existing, com- plex scheme of U.S. trade law. This article offers a complete account of the laws and regulations implementing the embargo, analyzes the defects in the regulatory scheme, and recommends ways to strengthen the em- bargo. The first part outlines the background of the imposition of the embargo, while the next three parts examine the regulations that govern American exports to South Africa and explore the loopholes in these reg- ulations that hinder their effectiveness. Part II discusses items on the t J.D. Candidate, Yale University. 1. Congress recently imposed various sanctions on South Africa. See Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986, Pub. -

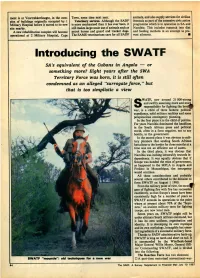

Introducing the SWATF

ment is at Voortrekkerhoogte, in the com Town, some time next year. animals, and also supply services for civilian plex of buildings originally occupied by 1 Veterinary services. Although the SADF livestock as part of the extensive civic action Military Hospital before it moved to its new is more mechanised than it has ever been, it programme which is in operation in SA and site nearby. still makes large-scale use of animals such as Namibia. This includes research into diet A new rehabilitation complex will become patrol horses and guard and tracker dogs. and feeding methods in an attempt to pre operational at 2 Military Hospital, Cape The SAMS veterinarians care for all SADF vent ailments. ■ Introducing the SWATF SA’s equivalent of the Cubans in Angola — or something more? Eight years after the SWA Territory Force was born, it is still often condemned as an alleged "surrogate force," but that is too simplistic a view WATF, now around 21 000-strong and swiftly assuming more and more S responsibility for fighting the bord(^ war, is a child of three fathers: political expediency, solid military realities and some perspicacious contingency planning. In the first place it is the child of politics. For years Namibia dominated the headlines in the South African press and political world, often in a form negative, not to say hostile, to the government. In the second place it was obvious to mili tary planners that sending South African battalions to the border for three months at a time was not an efficient use of assets. -

New Contracts

Third Issue 2015 New Contracts Milestone to Boost Denel’s Agreement with UN, Armoured a Huge Benefit for Vehicle Business Mechem’s Business Dubai Airshow an Opportunity Denel Support for Denel to Market its Enables Rapid Aerospace Capabilities Growth of Enterprise DENEL GROUP VALUES PERFORMANCE WE EMBRACE OPERATIONAL EXCELLENCE. INTEGRITY WE ARE HONEST, TRUTHFUL AND ETHICAL. INNOVATION WE CREATE SUSTAINABLE INVESTMENT SOLUTIONS. CARING WE CARE FOR OUR PEOPLE, CUSTOMERS, COMMUNITIES, NATIONS AND THE ENVIRONMENT. ACCOUNTABILITY WE TAKE RESPONSIBILITY FOR ALL OUR ACTIONS. Contents Issue highlights 2 Editor-in-Chief 3 Year-end Message from the Acting Group CEO 3 A Dozen Achievements – Top 12 Highlights of 2015 4 Accolades Keep Rolling in for Denel 4 Strong Support for Denel Demonstrated in Parliament 4 Young Engineers Conquer the Systems at Annual Challenge 05 5 New Contracts to Boost Denel’s Armoured Vehicle Business 6 Dubai Airshow an Opportunity to Market our Aerospace Capabilities 7 Strong Support for Growth of Ekurhuleni Aerotropolis in Gauteng 8 Iconic Denel Products Offer Backdrop for Paintball Warriors 9 Denel Support Enables Rapid Growth for Thuthuka 10 Denel Participates at SA Innovation Summit 09 10 Clever Robot Detects Landmines to Save Lives 11 Denel Products on Show in London 12 Milestone Agreement with UN Benefits Mechem Business 13 Training Links with Cameroon Grow Stronger 14 Empowering a Girl Child to Fly High 14 DTA Opens Doors to Training Opportunities 15 Denel Vehicle Systems Inspires Youthful Audience 12 15 High praise for Mechem team in Mogadishu 16 Preserving Denel’s Living Heritage 18 Celebrating Pioneering Women in Words and Pictures 20 Out and About in Society 16 Editor’s Note We would like to hear from you! Denel Insights has been created as an external communication platform to keep you – our stakeholders – informed about the projects and developments within our Group. -

The Rollback of South Africa's Chemical and Biological Warfare

The Rollback of South Africa’s Chemical and Biological Warfare Program Stephen Burgess and Helen Purkitt US Air Force Counterproliferation Center Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama THE ROLLBACK OF SOUTH AFRICA’S CHEMICAL AND BIOLOGICAL WARFARE PROGRAM by Dr. Stephen F. Burgess and Dr. Helen E. Purkitt USAF Counterproliferation Center Air War College Air University Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama The Rollback of South Africa’s Chemical and Biological Warfare Program Dr. Stephen F. Burgess and Dr. Helen E. Purkitt April 2001 USAF Counterproliferation Center Air War College Air University Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama 36112-6427 The internet address for the USAF Counterproliferation Center is: http://www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/awc-cps.htm . Contents Page Disclaimer.....................................................................................................i The Authors ............................................................................................... iii Acknowledgments .......................................................................................v Chronology ................................................................................................vii I. Introduction .............................................................................................1 II. The Origins of the Chemical and Biological Warfare Program.............3 III. Project Coast, 1981-1993....................................................................17 IV. Rollback of Project Coast, 1988-1994................................................39 -

Wrecking Ball

WRECKING BALL Why Permanent Technological Unemployment, a Predictable Pandemic and Other Wicked Problems Will End South Africa’s Experiment in Inclusive Democracy by Stu Woolman TERMS of USE This electronic version of the book is available exclusively on the NISC website for free download to use in research or private study. It may not be re-posted on book or other digital repositories that allow systematic sharing or download. For any commercial or other uses please contact the publishers, NISC (Pty) Ltd. Print copies of this book as well as e-Book versions available for online ordering from the African Books Collective and Amazon.com. © NISC (Pty) Ltd WRECKING BALL Why permanent technological unemployment, a predictable pandemic and other wicked problems will end South Africa’s experiment in inclusive democracy Wrecking Ball explores, in an unprecedented manner, a decalogue of wicked problems that confronts humanity: Nuclear proliferation, climate change, pandemics, permanent technological unemployment, Orwellian public and private surveillance, social media that distorts reality, cyberwarfare, the fragmentation of democracies, the inability of nations to cabin private power, the failure of multinational institutions to promote collaboration and the deepening of autocratic rule in countries that have never known anything but extractive institutions. Collectively, or even severally, these wicked problems constitute crises that could end civilisation. Does this list frighten you, or do you blithely assume that tomorrow will be just like yesterday? Wrecking Ball shows that without an inclusive system of global governance, the collective action required to solve those wicked problems falls beyond the remit of the world’s 20 inclusive democracies, 50 flawed democracies and 130 extractive, elitist autocracies. -

Betrayal of the Promise: How South Africa Is Being Stolen

BETRAYAL OF THE PROMISE: HOW SOUTH AFRICA IS BEING STOLEN May 2017 State Capacity Research Project Convenor: Mark Swilling Authors Professor Haroon Bhorat (Development Policy Research Unit, University of Cape Town), Dr. Mbongiseni Buthelezi (Public Affairs Research Institute (PARI), University of the Witwatersrand), Professor Ivor Chipkin (Public Affairs Research Institute (PARI), University of the Witwatersrand), Sikhulekile Duma (Centre for Complex Systems in Transition, Stellenbosch University), Lumkile Mondi (Department of Economics, University of the Witwatersrand), Dr. Camaren Peter (Centre for Complex Systems in Transition, Stellenbosch University), Professor Mzukisi Qobo (member of South African research Chair programme on African Diplomacy and Foreign Policy, University of Johannesburg), Professor Mark Swilling (Centre for Complex Systems in Transition, Stellenbosch University), Hannah Friedenstein (independent journalist - pseudonym) Preface The State Capacity Research Project is an interdisciplinary, inter- that the individual confidential testimonies they were receiving from university research partnership that aims to contribute to the Church members matched and confirmed the arguments developed public debate about ‘state capture’ in South Africa. This issue has by the SCRP using largely publicly available information. This dominated public debate about the future of democratic governance triangulation of different bodies of evidence is of great significance. in South Africa ever since then Public Protector Thuli Madonsela published her report entitled State of Capture in late 2016.1 The The State Capacity Research Project is an academic research report officially documented the way in which President Zuma and partnership between leading researchers from four Universities senior government officials have colluded with a shadow network of and their respective research teams: Prof. Haroon Bhorat from the corrupt brokers. -

South African Aerospace and Defence Ecosystem MASTERPLAN 2020

Aerospace and Defence- Final Masterplan 2020 South African Aerospace and Defence Ecosystem MASTERPLAN 2020 Francois Denner;Philip Haupt;Khalid Manjoo;Jessie Ndaba;Linden Petzer;Josie Rowe-Setz. Defence Experts: H Heitman, CM Zondi BLUEPRINT | Page Aerospace and Defence- Final Masterplan 2020 Acronyms A&D Aerospace & Defence AfCFTA African Continental Free Trade Area AISI Aerospace Industry Support Initiative AMD Aerospace Maritime Defence (Industries Association) AMO Approved Maintenance Organisation APDP Automotive Production and Development Programme BASA Bilateral Aviation Safety Agreement BB BEE Broad Based Black Economic Empowerment CAA Civil Aviation Authority CAASA Commercial Aviation Association CAIDS Commercial Aerospace Industry Development Strategy CAMASA Commercial Aerospace Manufacturing Association CAV Centurion Aerospace Village CIS Communications and Information Services CSIR Council for Scientific and Industrial Research COTS Commercial Off the Shelf CSPD Competitive Supplier Development Programme CTK Cargo & mail Tonne/Km DARPA Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency DCAC Directorate of Conventional Arms Control DCDT Department of Communications and Digital Technologies DFI Development Finance Institution DHET Department of Higher Education and Training DIP Defence Industrial Participation DIRCO Department of International Relations and Cooperation DoD Department of Defence (South Africa) DPE Department of Public Enterprises DSI Department of Science and Innovation DTIC Department of Trade, Industry and Competition -

Denel Group Integrated Report Twenty 15/16

DENEL GROUP INTEGRATED REPORT TWENTY 15/16 Reliable Defence Security and Technology Solutions Partner “He who refuses to obey cannot command.” ~Kenyan proverb DENEL ABOUT THIS REPORT REPORTING FRAMEWORKS REPORTING BOUNDARY ASSURANCE » This report takes cognisance of the » This integrated report presents a » The external auditors were engaged integrated reporting requirements transparent, comprehensive and to assure financial information, of the King III Report on Corporate comparable view of the financial, whilst most of the non-financial Governance and the International operating, social and sustainability information presented in this integrated Integrated Reporting Framework. performance of Denel SOC Ltd to a report was assured by a number of » This report contains some elements broad range of stakeholders for the service providers through various of standard disclosures of one of the year ended 31 March 2016. processes, i.e. B-BBEE verification, ISO globally recognised best reporting » Non-financial information presented certification, organisational climate practices frameworks, the Global in the report relates to Denel, its assessment, etc. Reporting Initiative (GRI G4). operating business units, subsidiaries » The GRI G4 indicators are included and associated companies, unless in the GRI content index. The otherwise stated. This report outlines the index is provided on pages 230 » Financial information includes to 234 and indicates Denel’s full, information regarding associated group’s outlook and partially or non compliance against companies. reporting indicators. Where data further aims to highlight measurement techniques are not in opportunities and challenges faced by Denel, place, descriptions of the relevant compliance activities are provided. as well as planned actions to address the same. -

Aerospace Industry Support Initiative Impact Report 2015/16

AEROSPACE INDUSTRY SUPPORT INITIATIVE IMPACT REPORT 2015/16 AN INITIATIVE OF THE DEPARTMENT OF TRADE AND INDUSTRY, MANAGED AND HOSTED BY THE CSIR Cover image: The CAT 200 KS Small Gas Turbine Engine prototype, made possible with AISI support to place South Africa in the lead in terms of state-of-the-art micro gas turbines (see page 40). AISI Vision To position South African aerospace and defence related industry as a global leader, in niche areas, whilst ensuring effective interdepartmental participation and collaboration. AISI Mission To enhance the global competitiveness of the South African aerospace and defence industry by: Developing relevant industry focused capabilities and facilitate associated transfer of technology to industry Providing a platform for facilitating partnerships and collaboration amongst government, industry and academia, locally and internationally Identifying, developing, supporting and promoting the interests and capabilities of the South African aerospace and defence industry Accelerating the achievement of government strategic objectives including growth, employment and equity. 2 • AISI Impact Report 2015/16 Contents Picturegraphic ............................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Executive summary ...................................................................................................................................................................................