Child Protective Services: a Guide for Caseworkers 2018 Child Protective Services: a Guide for Caseworkers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State Definitions of Child Abuse and Neglect

State Definitions Of Child Abuse and Neglect ORC 2151.031 Abused child defined As used in this chapter, an “abused child” includes any child who: (A) Is the victim of “sexual activity” as defined under Chapter 2907. of the Revised Code, where such activity would constitute an offense under that chapter, except that the court need not find that any person has been convicted of the offense in order to find that the child is an abused child; (B) Is endangered as defined in section 2919.22 of the Revised Code, except that the court need not find that any person has been convicted under that section in order to find that the child is an abused child; (C) Exhibits evidence of any physical or mental injury or death, inflicted other than by accidental means, or an injury or death which is at variance with the history given of it. Except as provided in division (D) of this section, a child exhibiting evidence of corporal punishment or other physical disciplinary measure by a parent, guardian, custodian, person having custody or control, or person in loco parentis of a child is not an abused child under this division if the measure is not prohibited under section 2919.22 of the Revised Code. (D) Because of the acts of his parents, guardian, or custodian, suffers physical or mental injury that harms or threatens to harm the child’s health or welfare. (E) Is subjected to out-of-home care child abuse. ORC 2151.03 Neglected child defined - failure to provide medical or surgical care for religious reasons (A) As used in this chapter, “neglected child” -

Tall Poppies, Cut Grass, and the Fear of Being Envied

Chapter Seven Tall Poppies, Cut Grass, and the Fear of Being Envied Just mention the words “beauty pageant” to some women and watch the claws come out. —Tamara Henry, former Miss Arkansas USA I have this beautiful engagement ring that my fiancé gave me and I won’t show it to any of my family because I know that there’s going to be static around it. —Roberta, 30-something professional TALL POPPY SYNDROME Throughout this book, there are instances of phenomena surrounding envy for which we don’t have exact English expressions, such as schadenfreude (defined in Chapter 1) or the lack of a word for “benign envy” (discussed in Chapter 4). Another example is the concept of “tall poppy syndrome,” which is more commonly discussed in Australia and New Zealand than in the United States. A “tall poppy” is anyone who stands out because of rank, success, good looks, or any other characteristic that might incite envy in other people. To “tall poppy” someone is to cut this person down to size, and “tall poppy syndrome” refers to the tall poppying of tall poppies. We had a similar expression on the kibbutz. We commented bitterly about the need to “cut the grass to uniform height,” referring to the kibbutz’s tendency to reward those who went along with the flow and to punish those who tried to do something differently or stand out in any way. It is interesting the way in which both metaphors portray the chopping down of something 63 64 Chapter 7 naturally beautiful to conform to someone else’s sense of how things should be. -

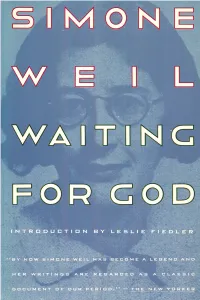

Waiting for God by Simone Weil

WAITING FOR GOD Simone '111eil WAITING FOR GOD TRANSLATED BY EMMA CRAUFURD rwith an 1ntroduction by Leslie .A. 1iedler PERENNIAL LIBilAilY LIJ Harper & Row, Publishers, New York Grand Rapids, Philadelphia, St. Louis, San Francisco London, Singapore, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto This book was originally published by G. P. Putnam's Sons and is here reprinted by arrangement. WAITING FOR GOD Copyright © 1951 by G. P. Putnam's Sons. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written per mission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address G. P. Putnam's Sons, 200 Madison Avenue, New York, N.Y.10016. First HARPER COLOPHON edition published in 1973 INTERNATIONAL STANDARD BOOK NUMBER: 0-06-{)90295-7 96 RRD H 40 39 38 37 36 35 34 33 32 31 Contents BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Vll INTRODUCTION BY LESLIE A. FIEDLER 3 LETTERS LETTER I HESITATIONS CONCERNING BAPTISM 43 LETTER II SAME SUBJECT 52 LETTER III ABOUT HER DEPARTURE s8 LETTER IV SPIRITUAL AUTOBIOGRAPHY 61 LETTER v HER INTELLECTUAL VOCATION 84 LETTER VI LAST THOUGHTS 88 ESSAYS REFLECTIONS ON THE RIGHT USE OF SCHOOL STUDIES WITII A VIEW TO THE LOVE OF GOD 105 THE LOVE OF GOD AND AFFLICTION 117 FORMS OF THE IMPLICIT LOVE OF GOD 1 37 THE LOVE OF OUR NEIGHBOR 1 39 LOVE OF THE ORDER OF THE WORLD 158 THE LOVE OF RELIGIOUS PRACTICES 181 FRIENDSHIP 200 IMPLICIT AND EXPLICIT LOVE 208 CONCERNING THE OUR FATHER 216 v Biographical 7\lote• SIMONE WEIL was born in Paris on February 3, 1909. -

Child Abuse Packet for KIDS

Child Abuse Signs & Symptoms; Attitudes & Actions What is Child Abuse? Child abuse, or child maltreatment, is an act by a parent or caretaker that results in or allows the child to be subjected to death, physical injury, sexual assault, or emotional harm. Emotional abuse, neglect, physical abuse, and sexual abuse are all different forms of child abuse. Child abuse is more than bruises and broken bones. While physical abuse might be the most visible, other types of abuse, such as emotional abuse and neglect, also leave deep, lasting scars. The earlier abused children get help, the greater chance they have to heal and break the cycle—rather than perpetuating it. By learning about common signs of abuse and what you can do to intervene, you can make a huge difference in a child’s life. Types of Child Abuse There are several types of child abuse, but the core element that ties them together is the emotional effect on the child. Children need predictability, structure, clear boundaries, and the knowledge that their parents are looking out for their safety. Abused children cannot predict how their parents will act. Their world is an unpredictable, frightening place with no rules. Whether the abuse is a slap, a harsh comment, stony silence, or not knowing if there will be dinner on the table tonight, the end result is a child that feels unsafe, uncared for, and alone. Emotional child abuse Sticks and stones may break my bones but words will never hurt me? Contrary to this old saying, emotional abuse can severely damage a child’s mental health or social development, leaving lifelong psychological scars. -

Exploring Children's Views and Experiences of Having a Learning

Exploring Children’s Views and Experiences of Having a Learning Difficulty and the Support They Receive at School Abigail Wilson A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of East London for the degree of Doctor of Applied Educational and Child Psychology April 2017 Word count: 38, 494 P a g e i Abstract Few studies have focused on gaining the views and experiences of primary aged children with the highest level of SEN – those with Statements of SEN (SSEN) or Education, Health and Care Plans (EHCPs). This exploratory study aimed to understand from the perspective of children with moderate or general learning difficulties what they think of school, the additional support they receive, and what they would change about it in the future. It also aimed to investigate the extent to which these children are involved in the decision- making process around their provision and whether their views are considered. Six children were interviewed using pictorial prompts and the data were transcribed and analysed thematically from a social constructivist standpoint. The study found that the pupils with SSEN or EHCPs held generally positive views of schools, preferred creative subjects, but experienced a range of difficulties at school. Friends and the support of a considerate adult were viewed as important elements of school. However, close TA support and appearing different from their learning-abled peers seems to promote physical isolation, a lack of agency and bullying. Pupils placed more value on support linked to developing their interaction skills rather than support that helped them to learn, or support related to changes in their environment. -

Economic and Social Research Council End of Award Report

To cite this output: Dyson, SM, et al (2011) Education for Minority Ethnic Pupils: Young People with Sickle Cell Disease ESRC End of Award Report, RES-000-23-1486. Swindon: ESRC ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL RESEARCH COUNCIL END OF AWARD REPORT For awards ending on or after 1 November 2009 This End of Award Report should be completed and submitted using the grant reference as the email subject, to [email protected] on or before the due date. The final instalment of the grant will not be paid until an End of Award Report is completed in full and accepted by ESRC. Grant holders whose End of Award Report is overdue or incomplete will not be eligible for further ESRC funding until the Report is accepted. ESRC reserves the right to recover a sum of the expenditure incurred on the grant if the End of Award Report is overdue. (Please see Section 5 of the ESRC Research Funding Guide for details.) Please refer to the Guidance notes when completing this End of Award Report. Grant Reference RES-000-23-1486 Grant Title Education for Minority Ethnic Pupils: Young People with Sickle Cell Disease Grant Start Date 1st September Total Amount £ 231,108.77 2006 Expended: Grant End Date 28th February 2011 Grant holding De Montfort University Institution Grant Holder Professor Simon M Dyson Grant Holder’s Contact Address Email Details Hawthorn Building [email protected] De Montfort University Telephone Leicester LE1 9BH (0116) 257 7751 Co-Investigators (as per project application): Institution Dr Sue E Dyson De Montfort University Professor Lorraine Culley De Montfort University Professor Karl Atkin University of York Dr Jack Demaine Loughborough University 1 To cite this output: Dyson, SM, et al (2011) Education for Minority Ethnic Pupils: Young People with Sickle Cell Disease ESRC End of Award Report, RES-000-23-1486. -

Children's Participation in Child Protection

CHILDREN’S PARTICIPATION IN CHILD PROTECTION Tool 4 www.keepingchildrensafe.org.uk Copyright © Keeping Children Safe Coalition 2011 Graphics & Layout www.ideenweberei.com Produced by the Keeping Children Safe Coalition Contents Introduction ...................................................................................................................................................2 Module One: Children recognise what is child abuse ................................................................................10 Exercise 1.1: Children’s rights .............................................................................................. 11 Exercise 1.2: Feeling safe and unsafe .................................................................................. 18 Exercise 1.3: Understanding child abuse ............................................................................. 22 Module Two: Children keeping themselves and others safe ..............................................................................................38 Exercise 2.1: Talking about feelings ..................................................................................... 38 Exercise 2.2: Decision-making ............................................................................................. 44 Exercise 2.3: Children keeping children safe ....................................................................... 49 Module Three: Making organisations feel safe for children................................................................................................56 -

Case Management Chapter Contents Staff Profiles – General Profile

4: Individuals – Case Management Chapter Contents Staff Profiles – General Profile ..................................................................................................................... 4-2 Summary Tab ....................................................................................................................................................... 4-2 Summary Tab – Case Summary Panel ..............................................................................................................4-2 Summary Tab – Chronological Case History Panel ...........................................................................................4-7 Summary Tab – Individual Information Panel ..................................................................................................4-8 Summary Tab – Verification Summary Panel ..................................................................................................4-9 Case Notes Tab .................................................................................................................................................. 4-12 Create a Case Note Template ......................................................................................................................... 4-13 Add a Case Note............................................................................................................................................ 4-15 Activities Tab .................................................................................................................................................... -

The Relationship Between Child Protection Workers and School Social Workers

St. Catherine University SOPHIA Master of Social Work Clinical Research Papers School of Social Work 3-2014 The Relationship Between Child Protection Workers and School Social Workers Daniel S. Gibbel St. Catherine University Follow this and additional works at: https://sophia.stkate.edu/msw_papers Part of the Social Work Commons Recommended Citation Gibbel, Daniel S.. (2014). The Relationship Between Child Protection Workers and School Social Workers. Retrieved from Sophia, the St. Catherine University repository website: https://sophia.stkate.edu/ msw_papers/317 This Clinical research paper is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Social Work at SOPHIA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Social Work Clinical Research Papers by an authorized administrator of SOPHIA. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running Head: Relationships Between Social Service Colleagues The Relationship Between Child Protection Workers and School Social Workers Daniel S. Gibbel MSW Clinical Research Paper Presented to the Faculty of School of the Social of Social Work St. Catherine University and the University of St. Thomas St. Paul, Minnesota In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Social Work Committee Members Karen Carlson, Ph.D. (Chair) Dana Hagemann, LSW Tricia Sedlacek MSW, LGSW The Clinical Research Project is a graduation requirement for MSW students at St. Catherine University/University of St. Thomas School of Social Work in St. Paul, Minnesota and is conducted within a nine-month time frame to demonstrate facility with basic social research methods. Students must independently conceptualize a research problem, formulate a research design that is approved by a research committee and the university Institutional Review Board, implement the project, and publicly present the findings of the study. -

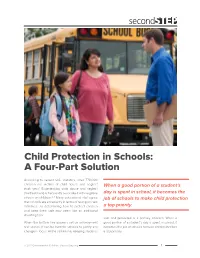

Child Protection in Schools: a Four-Part Solution

Child Protection in Schools: A Four-Part Solution According to recent U.S. statistics, over 770,000 children are victims of child abuse and neglect When a good portion of a student’s each year.1 Experiencing child abuse and neglect (maltreatment) is frequently associated with negative day is spent in school, it becomes the effects on children.2, 3 Many educational staff agree job of schools to make child protection that schools are at capacity in terms of taking on new initiatives, so determining how to protect children a top priority. and keep them safe may seem like an additional daunting task. safe and protected is a primary concern. When a When the bottom line appears set on achievement good portion of a student’s day is spent in school, it test scores, it can be hard for schools to justify any becomes the job of schools to make child protection change in focus. At the same time, keeping students a top priority. © 2014 Committee for Children ∙ SecondStep.org 1 priority and motivate staff to implement skills learned Four Components of School-Based Child Protection in training. Research by Yanowitz and colleagues6 underscores the importance of emphasizing policies Policies and Procedures and procedures in child abuse training within the Sta Training school setting. Student Lessons Family Education Administrators must assess their current child protection policies, Research indicates the most effective way to procedures and practices to develop do this is by training adults—all school staff and a comprehensive child protection caregivers—and teaching students skills.4, 5, 6 This can be accomplished by creating and implementing strategy for their school. -

Differences in Narcissistic Presentation in Abused and Non- Abused Children and Adolescents

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Summer 8-2014 Differences in Narcissistic Presentation in Abused and Non- Abused Children and Adolescents Mallory Laine Malkin University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Applied Behavior Analysis Commons, Child Psychology Commons, Clinical Psychology Commons, School Psychology Commons, and the Social Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Malkin, Mallory Laine, "Differences in Narcissistic Presentation in Abused and Non-Abused Children and Adolescents" (2014). Dissertations. 274. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/274 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi DIFFERENCES IN NARCISSISTIC PRESENTATION IN ABUSED AND NON-ABUSED CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS by Mallory Laine Malkin Abstract of a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2014 ABSTRACT DIFFERENCES IN NARCISSISTIC PRESENTATION IN ABUSED AND NON-ABUSED CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS by Mallory Laine Malkin August 2014 The present study examined whether children and adolescents who have been victims of sexual or physical abuse report higher levels of narcissistic tendencies than children and adolescents who have not been victims of abuse. Inaddition to narcissism, internalizing symptoms, externalizing behaviors, and risky behaviors were evaluated, as such issues have been associated with both maltreatment (Baer & Maschi, 2003) and narcissism (Barry & Malkin, 2010; Bushman & Baumeister, 1998). -

November 19, 2020 at 9:00 A.M., Notice Having Been Published 5 in the Richmond Times-Dispatch November 2, 2020 and November 9, 6 2020

MINUTES OF THE REGULAR MEETING OF THE BOARD OF ZONING APPEALS OF 2 HENRICO COUNTY, HELD IN THE COUNTY ADMINISTRATION BUILDING IN THE 3 GOVERNMENT CENTER AT PARHAM AND HUNGARY SPRING ROADS, ON 4 THURSDAY NOVEMBER 19, 2020 AT 9:00 A.M., NOTICE HAVING BEEN PUBLISHED 5 IN THE RICHMOND TIMES-DISPATCH NOVEMBER 2, 2020 AND NOVEMBER 9, 6 2020. 7 8 9 Members Present: Terone B. Green, Chair 10 Walter L. Johnson, Jr. , Vice-Chair 11 Gentry Bell 12 Terrell A. Pollard 13 James W. Reid 14 15 Also Present: Benjamin Blankinship, Secretary 16 Leslie A. News, Senior Principal Planner 17 Paul M. Gidley, County Planner 18 R. Miguel Madrigal, County Planner 19 Rosemary Deemer, County Planner 20 Kristin Smith, County Planner 21 Kuronda Powell, Account Clerk 22 23 24 Mr. Green - Good morning and welcome to the November 19, 2020 25 meeting of the Henrico County Board of Zoning Appeals. Would those who are able to 26 stand , please join us for the Pledge of Allegiance. 27 28 [Recitation of the Pledge of Allegiance] 29 30 Mr. Green - Mr. Blankinship will now read our rules. 31 32 Mr. Blankinship - Good morning, Mr. Chair, members of the Board , good 33 morning to those of you who are in the room with us today. There are also two remote 34 options for participating in this meeting. There is a livestream on the Planning Department 35 webpage, and we are hosting a video conference using Webex. I'd like to welcome 36 everyone who is joining us remotely. 37 38 If you wish to observe the meeting , but you do not intend to speak, welcome and thank 39 you for joining us.