Polyakova I. Collecting Amber Naturalia in Sixteenth-Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lithuania & Latvia: the Baltics

VBT Itinerary by VBT www.vbt.com Lithuania & Latvia: the Baltics Bike Vacation + Air Package Ancient and modern history unfurl before you as you explore two contrasting countries on this Baltic bike tour. The eclectic capitals of Lithuania and Latvia frame your discoveries, as you venture from the storied Curonian Spit—a UNESCO World Heritage site—and along the Baltic coast into a bucolic countryside. Along the way, you’ll probe each distinctive culture as you explore the Amber Museum and an amber craftsman’s workshop, visit an organic herb farm, embark on guided walking tours of parks and cities, cruise the canals of Riga’s Old Town, and discover the lasting influences of the Soviet era at a former missile site. Special meals including an authentic Lithuanian barbecue and overnights at some of the region’s finest accommodations round out this amazing experience. Cultural Highlights An Underground Look at the Cold War: At the end of World War II, tensions between former allies 1 / 10 VBT Itinerary by VBT www.vbt.com the United States and the Soviet Union erupted into a Cold War arms race. Both nations developed and stockpiled atomic weapons until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. You will explore one of the Soviet Union’s underground missile sites during your tour. Admire the view as you cycle through a bucolic countryside and along the Baltic coast. Delve into the region’s Soviet history on a tour of the Cold War Museum, located in a former underground missile site. Discover ancient herbal and medicinal tea recipes dating back to Pagan times on a visit to an organic herb farm. -

Couronians | Semigallians | Selonians

BALTS’ ROAD, THE COURONIAN ROUTE SEGMENT Route: Rucava – Liepāja – Grobiņa – Jūrkalne – Alsunga – Kuldīga – Ventspils – Talsi – Valdemārpils – Sabile – Saldus – Embūte – Mosėdis – Plateliai – Kretinga – Klaipėda – Palanga – Rucava Duration: 3–4 days. Length about 790 km In ancient times, Couronians lived on the coast of the Baltic Sea. At that time, the sea and rivers were an important waterway that inuenced their way of life and interaction with neighbouring nations. You will nd out about this by taking the circular Couronian Route Segment. Peaceful deals were made during trading. Merchants from faraway lands Macaitis, Tērvete Tourism Information Centre, Zemgale Planning Region. Planning Zemgale Centre, Information Tourism Tērvete Macaitis, were tempted to visit the shores of the Baltic Sea looking for the northern gold – Photos: Līva Dāvidsone, Artis Gustovskis, Arvydas Gurkšnis, Denisas Nikitenka, Mindaugas Mindaugas Nikitenka, Denisas Gurkšnis, Arvydas Gustovskis, Artis Dāvidsone, Līva Photos: Publisher: Kurzeme Planning Region, Zemgale Planning Region 2019 Region Planning Zemgale Region, Planning Kurzeme Publisher: amber. To nd out more about amber, visit the Palanga Amber Museum (40) Centre, National Regional Development Agency in Lithuania. in Agency Development Regional National Centre, and the Liepāja Crafts House (6). Ancient Couronian boats, the barges, are Authors: Kurzeme Planning Region, Zemgale Planning Region, Šiauliai Tourism Information Information Tourism Šiauliai Region, Planning Zemgale Region, Planning Kurzeme Authors: -

Country Profile Lithuania

Country Profile Lithuania Last updated: February 2020 This profile was prepared and updated by Audronė Rimkutė (Vilnius University). The opinions expressed in this profile are those of the author and are not official statements of the government or of the Compendium editors. It is based on official and non-official sources addressing current cultural policy issues. Additional national cultural policy profiles are available on: http://www.culturalpolicies.net If the entire profile or relevant parts of it are reproduced in print or in electronic form including in a translated version, for whatever purpose, a specific request has to be addressed to the Association of the Compendium of Cultural Policies and Trends. Such reproduction must be accompanied by the standard reference below, as well as by the name of the author of the profile. Standard Reference: Association of the Compendium of Cultural Policies and Trends, "Compendium of Cultural Policies and Trends," 20th edition 2020. Available under:<https://www.culturalpolicies.net>>. ISSN: 2222-7334. 1 1. Cultural policy system ..................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1. Objectives, main features and background ....................................................................................... 4 1.2. Domestic governance system .............................................................................................................. 7 1.2.1. Organisational organigram .............................................................................................................. -

Tour Only (PDF)

VBT Itinerary by VBT www.vbt.com Lithuania & Latvia: the Baltics Bike Vacation + Air Package Ancient and modern history unfurl before you as you explore two contrasting countries on this Baltic bike tour. The eclectic capitals of Lithuania and Latvia frame your discoveries, as you venture from the storied Curonian Spit—a UNESCO World Heritage site—and along the Baltic coast into a bucolic countryside. Along the way, you’ll probe each distinctive culture as you explore the Amber Museum and an amber craftsman’s workshop, visit an organic herb farm, embark on guided walking tours of parks and cities, cruise the canals of Riga’s Old Town, and discover the lasting influences of the Soviet era at a former missile site. Special meals including an authentic Lithuanian barbecue and overnights at some of the region’s finest accommodations round out this amazing experience. Cultural Highlights An Underground Look at the Cold War: At the end of World War II, tensions between former allies 1 / 10 VBT Itinerary by VBT www.vbt.com the United States and the Soviet Union erupted into a Cold War arms race. Both nations developed and stockpiled atomic weapons until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. You will explore one of the Soviet Union’s underground missile sites during your tour. Admire the view as you cycle through a bucolic countryside and along the Baltic coast. Delve into the region’s Soviet history on a tour of the Cold War Museum, located in a former underground missile site. Discover ancient herbal and medicinal tea recipes dating back to Pagan times on a visit to an organic herb farm. -

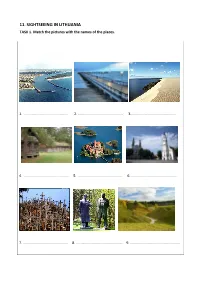

11. Sightseeing in Lithuania Task 1

11. SIGHTSEEING IN LITHUANIA TASK 1. Match the pictures with the names of the places. 1. ........................................... 2. ............................................ 3............................................. 4. ............................................ 5. ........................................... 6. ............................................. 7. ………………………………………… 8. ………………………………………….. 9. …………………………………………….. Trakai Castle The Port of Klaipėda Kaunas Town Hall Square Palanga Pier Grūtas Park (museum of Soviet monuments) Rumšiškės Ethnographic Museum The Hill of Crosses The Hill Forts of Kernavė The Sand Dunes of the Curonian Spit TASK 2. Read the text (on the next page) and match the headings with the paragraphs. The Baltic Sea Coast Countryside Leisure Introduction Main Cities National Heritage National Parks Regions TASK 3. Read the text again and decide if these ideas are expressed in the text. Tick (✓) the box if the ideas are mentioned or put a cross (x) if the ideas are not in the text. 1. The Old Town of Vilnius is one of the largest surviving medieval old towns in Europe. 2. Lithuania’s history is reflected in its cultural heritage. 3. People from different ethnographic regions use different dialects of Lithuanian. 4. Lithuanian towns have interesting architecture. 5. National parks should be visited by tourists. 6. There are many forests in Žemaitija national park. 7. The pinewoods of Dzūkija are full of mushrooms. 8. The Curonian Spit has an exceptional landscape. 9. Trakai has a small population of Karaites -

The Program of My Region

The program of my region Klaipėda 3 results Klaipėda, --None --, Palanga Palanga Amber Museum Vytauto g. 17 00101 Palanga Palanga Amber Museum was established in 1963 in a former manor on the Baltic seashore. It is a centre of amber collecting, examining, restoration, conservation etc. It includes a big archaeological hall with findings dating back to the Stone age. Open house Open Restorers' Workshop Representing restoration specificities of archeological works in the exposition hall of Palanga Amber Museum. Examining the tiniest details of the exhibits with the aid of digital microscope. Restorer Vytautė Lukšėnien ; Researcher and Curator of the Palanga Amber Museum Collection Dr. Sigita Bagužaitė-Talačkienė. Free Sunday 20 June de 11:00 à 13:00 et de 14:00 à 16:00 Saturday 19 June de 11:00 à 13:00 et de 14:00 à 16:00 General public Accessibility Mobility issues / wheelchair Workshop Let's Create Mosaic of Jūratė Castle Educational creative workshop on the sea shore. Senior educator Miglė Jonaitienė ; guide Julija Paškevičiūtė. Free Friday 18 June de 18:00 à 19:30 Children, Family Lecture The Balts’ Signs in Archaeological Works Theoretical introduction (lecture) to the Balts’ signs depicted on decorative surfaces of archaeological works, revealing the elements and signification of the signs. Dr. Sigita Bagužaitė-Talačkienė,Researcher and Curator of the Palanga Amber Museum Collection. Free Friday 18 June de 16:00 à 16:30 General public Accessibility Mobility issues / wheelchair Workshop Ancestors ’ Memory Imprints Educational workshop of plastic ceramics. Educator Giedrė Miežetienė ; Guide Julija Paškevičiūtė. Free Friday 18 June de 16:30 à 18:00 General public Accessibility Mobility issues / wheelchair Klaipėda, --None --, Neringa Coastal Stone Age. -

Lithuania a Place Worth Visiting!

Lithuania A place worth visiting! See it! Feel it! Love it! Contents Vilnius – a constantly changing city / 02 Kaunas – the provisional capital / 04 Klaipėda – the lively seaport / 05 Towns on water / 06 The Curonian Spit National Park / 08 Amber is more than gold / 10 Revitalize yourself in resorts / 12 The Homeland of oaks and storks / 14 Swim, ride, fly… get going! / 16 Ski all year round! / 18 Choose a conference venue / 20 Discover Lithuanian art / 22 Performances, operas, concerts / 24 Rumšiškės / 26 The Hill of Crosses / 27 Temptations of spring / 28 Joys of summer / 30 Gifts of autumn / 32 Mischieves of winter / 34 Gastronomic heritage / 36 Go shopping / 38 Lithuania in a nutshell / 40 www.Lithuania.travel Get to know Lithuania 03 See it! Feel it! Love it! 5th July, 2012 “…I first came to Lithuania when the snow was melting. I came here just by accident while travelling from West to East, from one old culture to another, totally different one. I was in a rush, so there were no plans to make a stop. However, when passing through Lithuania, a strange sense of space and freedom – unlike anywhere else – came into my heart. And an urge to return… Therefore, in summer I came here with my entire family. All-surrounding greenness heightened that intoxicating sense of space and freedom. I could not stop admiring the purest natural water springs, mineral water, overflowing abundance of lakes and rivers seeking to find their way to the sea. Even the rain! It is somehow different here – cosy, romantic, and calling to stumble into an old town bakery, smoked fish bistro or a small amber souvenir shop. -

Palanga Amber Museum

PALANGA AMBER MUSEUM Palanga Amber Museum is a division of the Lithuanian Art Museum in Palanga, displaying amber, its products and providing information on these topics. Located in the former Palanga estate. The museum is in the palace of the Count Feliksas Tiskevicius. They were built in 1897 according to the project of the German architect Franco Schwechten in the Palanga Birutė Forest, near the Baltic Sea, held by the local population. Palanga botanical park surrounded by the palace, which was started to form during the construction of the palace, in the 19th century. at the end The author of the park project is the French landscape architect Eduard Francois André. The museum holds over 28,000 amber exhibits, of which about 15,000 have inlays (have intrinsically stuck lives) [1] Exhibited about 4 500 amber articles, most of which are various articles or jewelry. HISTORY Amber was interested, it was collected by Palanga graph Feliksas Tiškevičius. Inclusions in the collection of collectors who have accumulated rare and valuable collections of amber, in the 20th century. In the first half of Lithuania there were quite a few, but nobody until the 20th century. In the early 1960s, they failed to gather these values into one place where they could be shown to the public and explored by scholars. The Palanga Amber Museum was founded in 1963. August 3 On behalf of the Ministry of Culture of the Lithuanian SSR. Exposition The museum's exposition covers 15 rooms with exhibits. The temporary exposition is stored in the chapel near the museum. -

Baltic Amber Way, 6 Days / 5 Nights, 3* and 4* Hotels

BALTIC AMBER WAY, 6 DAYS / 5 NIGHTS, 3* AND 4* HOTELS On our Baltic Amber Way tour you will get acquainted with the being of the amber in Latvia and Lithuania covering its history, output, procesing and jewelry. Day 1: Riga arrival Arrival in Riga, minivan or bus transfer to 4* hotel. Check-In Time at your leisure in Riga Overnight Day 2: Riga – Ventspils Buffet breakfast. Walking tour through Riga Old Town (~3 hrs) by seeing the most remarkable sights like St. Peter's Church with famous rooster, St. Jacobs Church, Dom Square and St. Dom Cathedral, where is placed one of the world's most valuable historic organs. The Powder Tower and city walls will make you feel the breath of the medieval. The guide will show and tell you about the oldest stone residential dwellings in Riga - the Three Brothers, the Great and Small Guilds were the central homes of two wealthy families of tradesmen and craftsmen, the fortification wall of Riga with theSwedish Gate - the only surviving gate to be found. Guide will introduce you with interesting story of Cat House and will show you Town Hall Squere with beautiful and elegant Blackheads House, which will delight lovers of glory. The tour will take visitors to Riga Castle, which was founded in 1330 but today serves as the official residence of the President of Latvia, the building of Parliament, the Monument of Liberty and fantastic Opera House. Continue your trip to Ventspils ( 3 hours bus drive) . Arrival and check in in the hotel. Time at your leisure in Ventspils Overnight Day 3: Ventspils-Pavilosta-Liepaja Buffet breakfast. -

Medical Use of Amber As a Subject of Exhibition and Educational Activities at Palanga Amber Museum

MEDICAL USE OF AMBER AS A SUBJECT OF EXHIBITION AND EDUCATIONAL ACTIVITIES AT PALANGA AMBER MUSEUM Regina Makauskienė Palanga Amber Museum, Lithuania [email protected] The Amber Museum in Palanga was established on August 3, 1963 in Tyszkiewicz Palace constructed in 1897 by the project of a German architect Franz Heinrich Schwechten (1841–1924). The Museum houses over 30,000 exhibits, among which is the collection of amber inclusions comprising of approximately 15,000 samples. For the history of Lithuania of special significance is the collection of archaeological amber, whose oldest finds, dating back to the Stone Age, give evidence of the culture of our ancestors and its strong bonds with amber. The Palanga Amber Museum is one of the most visited museums in Lithuania – approximately eight million eight hundred thousand citizens of Lithuania and foreign guests has visited it in the past 50 years. This has been the result of a purposeful development of a unique museum as a centre of amber collection, research and popularization. In April 2015, the project "Restoration of the representational Palace of the Palanga Amber Museum and its use for the needs of the present-day cultural tourism" was completely implemented. Owing to the project, the building infrastructure was totally renovated, and also a modern terminal for servicing visitors was established; as well as this, a centre for cultural meetings and educational activities for both children and adults was opened. Six displays dedicated to amber have been established at the Palanga Amber Museum in the past 50 years. The latest renewal was made in 2015 when a new show of amber (approximately six thousand items) was opened and the historical interiors of the aristocratic residence were reconstructed. -

I Love Palanga.Pdf

Norwegian Sea Skuodas PALANGA Kretinga Telðiai Ðiauliai Panevëþys FINLAND KLAIPËDA NORWAY Utena SWEDEN Nida Ðilutë North Atlantic Ocean ESTONIA RUSSIA Tauragë LATVIA Kaunas Nord Sea Baltic Sea IRELAND LITHUANIA VILNIUS UNITED KINGDOM LITHUANIA Marijampolë BELARUS NETHERLANDS POLAND GERMANY BELGIUM Flag Coat of Arms of Lithuania of the State Alytus CZECH REP. UKRAINE FRANCE SLOVAKIA Bay of Biscay MOLDOVA SWITZERLAND AUSTRIA Capital: Vilnius HUNGARY SLOVENIA ROMANIA National language: Lithuanian CROATIA ITALY Parliamentary System of governance: PORTUGAL BOS.& Black sea HER. democracy International memberships: SERBIA a member of NATO since 29 March 2004, a member SPAIN BULGARIA Geographical position: of European Union since 1 May 2004. Adriatic Residents: Sea MACEDONIA Lithuania is in the northeast of the eastern Baltic Sea ALBANIA coast. Lithuania shares borders with Belarus (660 population of about 2 million 979 thousand residents, Tyrrhenian Sea TURKEY km), Latvia (588 km), Poland (103 km) and Russia of which 84,2% are Lithuanians whose native GREECE Aegean along Kaliningrad region (273 km). The coastal strip language is Lithuanian (this language belongs to the Mediterranean Sea Ionian Sea Sea is 90 km long. The territory of the country is 65 300 m2. Indo - European language family and is one of the The distance from the north of the country to the oldest in Europe). Largest ethnic minorities of south is 276 km, and the distance from the west Lithuania are the Poles (6.6%), Russians (5.8 %), to the east is 373 km. In 1989 researchers of the and Belarusians (1.2 %). French National Institute found out that the Climate: geographical centre of Europe is in Lithuania, this The climate is maritime, continental. -

Lithuania.Travel

www.Lithuania.travel L i t h u a n i a Sacred traditions See you in Lithuania! E N Travel round cultural sites www.Lithuania.travel BELARUS LATVIA UNITED KINGDOM www.lithuaniatourism.co.uk FRANCE www.InfoTourLituanie.fr ITALY www.turismolituano.it Cover pictures by P. Gasiūnas. Pictures by R. Anusauskas, K. Kantautas, M. Kaminskas, N. Skrudupaitė, K. Stalnionytė, RUSSIA K. Driskius, V. Kirilovas, D. Vitkauskaitė, www.litinfo.ru V. Aukštaitis, A. Žygavičius, L. Ciūnys, L. Medelis, A. Žebrauskas, R. Eitkevičius, L. Druknerytė, Ž. Biržietytė, G. Lukoševičius. FINLAND www.liettua. / www.litauen.se Printed by JSC "Lodvila", 2012. GERMANY www.baltikuminfo.de POLAND Lithuanian State Department of Tourism POLAND www.litwatravel.com under The Ministry of Economy Gedimino pr. 38 / Vasario 16-osios g. 2, LT-01104 Vilnius, Lithuania SPAIN Tel. +370 70 664 976, fax +370 70 664 988 www.lituaniatur.com E-mail: [email protected] www. tourism.lt Cultural sites sites Cultural KALININGRAD REGION (RUSSIA) EU structural support 2007-2013 Seaport Airport centre information Tourist Not for sale. Baltic Sea You are in Lithuania! 011 You are in Lithuania! Trakai Castle You are in Lithuania. Experience the here for your entertainment. In Lithu- green surroundings: meadows and ania you can listen to world-class clas- hills are everywhere. Hear how the land sical music, watch numerous plays and is praised by the singing of birds. Five operas in the country’s 30 theatres and national parks are waiting for you to ex- enjoy high quality contemporary art. plore. Travel through refreshing forests, Need a good place for a conference, se- see cultural monuments: castles, anci- minar or meeting? Then look no further.