Svachchhata in the Settlement Or Slum Sanitation?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wadhwa Dukes Horizon

https://www.propertywala.com/wadhwa-dukes-horizon-mumbai Wadhwa Dukes Horizon - Chembur, Mumbai Wadhwa Dukes Horizon Wadhwa Dukes Horizon by Wadhwa Group at the very prime location of Chembur in Mumbai offers residential project that host 2, 2.5 and 3 bhk apartments in various sizes. Project ID: J791189512 Builder: Wadhwa Group Location: Wadhwa Dukes Horizon, Chembur, Mumbai - 400071 (Maharashtra) Completion Date: Dec, 2025 Status: Started Description Wadhwa Dukes Horizon by Wadhwa Group at the very prime location of Chembur in Mumbai offers residential project that host 2, 2.5 and 3 bhk apartments in the size ranges in between 537 to 1000 sqft. Wadhwa Dukes Horizon offers a host of facilities for residents. This includes Gymnasium. For families with kids, there is Children Play Area, etc. The project is well-connected to other parts of city by road, which passes through the heart of this suburb. Prominent shopping malls, movie theatres, school, and hospitals are present in proximity of this residential project. Amenities : Swimming Pool Children Play Area Gym Basketball Court Sewage Treatment Plant 24x7 Security The Wadhwa Group carries a rich legacy of over half a century, built on the trust and belief of its customers and stakeholders. The group is one of Mumbai’s leading real estate players and is currently developing residential, commercial and township projects spread across approximately 4.21 million Sq.M developed, ongoing & future. the group’s clientele comprises of over 20,000 satisfied customers and over 150+ MNC corporate. -

Mumbai District

Government of India Ministry of MSME Brief Industrial Profile of Mumbai District MSME – Development Institute Ministry of MSME, Government of India, Kurla-Andheri Road, Saki Naka, MUMBAI – 400 072. Tel.: 022 – 28576090 / 3091/4305 Fax: 022 – 28578092 e-mail: [email protected] website: www.msmedimumbai.gov.in 1 Content Sl. Topic Page No. No. 1 General Characteristics of the District 3 1.1 Location & Geographical Area 3 1.2 Topography 4 1.3 Availability of Minerals. 5 1.4 Forest 5 1.5 Administrative set up 5 – 6 2 District at a glance: 6 – 7 2.1 Existing Status of Industrial Areas in the District Mumbai 8 3 Industrial scenario of Mumbai 9 3.1 Industry at a Glance 9 3.2 Year wise trend of units registered 9 3.3 Details of existing Micro & Small Enterprises and artisan 10 units in the district. 3.4 Large Scale Industries/Public Sector undertaking. 10 3.5 Major Exportable item 10 3.6 Growth trend 10 3.7 Vendorisation /Ancillarisation of the Industry 11 3.8 Medium Scale Enterprises 11 3.8.1 List of the units in Mumbai district 11 3.9 Service Enterprises 11 3.9.2 Potentials areas for service industry 11 3.10 Potential for new MSME 12 – 13 4 Existing Clusters of Micro & Small Enterprises 13 4.1 Details of Major Clusters 13 4.1.1 Manufacturing Sector 13 4.2 Details for Identified cluster 14 4.2.1 Name of the cluster : Leather Goods Cluster 14 5 General issues raised by industry association during the 14 course of meeting 6 Prospects of training programmes during 2012 – 13 15 7 Action plan for MSME Schemes during 2012 – 13. -

New Horizon Tours

New Horizon Tours Presents INTOXICATING, INCREDIBLE INDIA MARCH 14 -MARCH 26, 2020 (LAX) Mar. 14, SAT: PARTICIPANTS from Los Angeles (LAX) board on Emirates air at 4.35PM Mar. 15, SUN: LAX PARTICIPANTS ARRIVE IN DUBAI AND CONNECT FLIGHT TO MUMBAI / Washington (IAD) participants depart at 11.10 AM Mar. 16, MON: ARRIVE MUMBAI Different times- LAX passengers arrive at 2.15AM (immediate occupancy of rooms- rooms reserved from Mar. 15). IAD passengers arrive at 2.00 PM- separate arrival transfers for each in Mumbai. Arrive in Mumbai, a cluster of seven islands derives its name from Mumba devi, the patron goddess of Koli fisher folk, the oldest habitants. Meeting assistance and transfer to Hotel. Rest of the day is free. Evening welcome dinner at roof top restaurant at Hotel near airport. HOTEL.OBEROI TRIDENT (Breakfast & Dinner for LAX passengers, Dinner only for IAD participants). Mar. 17, TUE: MUMBAI - CITY TOUR – BL Breakfast at Hotel. This morning embark on city tour of Mumbai visiting the British built Gateway of India, Bombay's landmark constructed in 1927 to commemorate Emperor George V's visit, the first State, ever to see India by a reigning monarch. Followed by a drive through the city to see the unique architecture, Mumbai University, Victoria Terminus, Marine Drive, Chowpatty Beach. Next stop at Hanging Gardens (now known as Sir K.P. Mehta Gardens), where the old English art of topiary is practiced. Continue to the Dhobi Ghat, an open-air laundry where washmen physically clean and iron hundreds of items of clothing, delivering them the next day. -

Periodical Report Periodical Report

ICTICT IncideIncidentsnts DatabaseDatabase PeriodicalPeriodical ReportReport January 2012 2011 The following is a summary and analysis of terrorist attacks and counter-terrorism operations that occurred during the month of January 2012, researched and recorded by the ICT database team. Among others: Irfan Ul Haq, 37 was sentenced to 50 months in prison on 5 January, for providing false documentation and attempting to smuggle a suspected Taliban member into the USA. On 5 January, Eyad Rashid Abu Arja, 47, a male Palestinian with dual Australian-Jordanian nationality, was sentenced to 30 months in prison in Israel for aiding Hamas. On 6 January, a bomb exploded in Damascus, Syria killing 26 people and wounding 63 others. ETA militant Andoni Zengotitabengoa, was sentenced on 6 January to 12 years in prison for the illegal possession of weapons, as well car theft, falsification of documents, assault and resisting arrest. On 9 January, Sami Osmakac, 25, was charged with plotting to attack crowded locations in Florida, USA. On 10 January, a car bomb exploded at a bus stand outside a shopping bazaar in Jamrud, northwestern Pakistan killing 26 people and injuring 72. Jermaine Grant, 29, a British man and three Kenyans were charged on 13 January in Mombasa, Kenya with possession of bomb-making materials and plotting to explode a bomb. On 13 January Thai police arrested Hussein Atris, 47, a Lebanese-Swedish man, who was suspected of having links to Hizballah. He was charged three days later with the illegal possession of explosive materials. On 14 January, a suicide bomber, disguised in a military uniform, killed 61 people and injured 139, at a checkpoint outside Basra, Iraq. -

Mumbai Residential June 2019 Marketbeats

MUMBAI RESIDENTIAL JUNE 2019 MARKETBEATS 2.5% 62% 27% GROWTH IN UNIT SHARE OF MID SHARE OF THANE SUB_MARKET L A U N C H E S (Q- o - Q) SEGMENT IN Q2 2019 IN LAUNCHES (Q2 2019) HIGHLIGHTS RENTAL VALUES AS OF Q2 2019* Average Quoted Rent QoQ YoY Short term Submarket New launches see marginal increase (INR/Month) Change (%) Change (%) outlook New unit launches have now grown for the third consecutive quarter, with 15,994 units High-end segment launched in Q2 2019, marking a 2.5% q-o-q increase. Thane and the Extended Eastern South 60,000 – 700,000 0% 0% South Central 60,000 - 550,000 0% 0% and Western Suburbs submarkets were the biggest contributors, accounting for around Eastern 25,000 – 400,000 0% 0% Suburbs 58% share in the overall launches. Eastern Suburbs also accounted for a notable 17% Western 50,000 – 800,000 0% 0% share of total quarterly launches. Prominent developers active during the quarter with new Suburbs-Prime Mid segment project launches included Poddar Housing, Kalpataru Group, Siddha Group and Runwal Eastern 18,000 – 70,000 0% 0% Suburbs Developers. Going forward, we expect the suburban and peripheral locations to account for Western 20,000 – 80,000 0% 0% a major share of new launch activity in the near future. Suburbs Thane 14,000 – 28,000 0% 0% Mid segment dominates new launches Navi Mumbai 10,000 – 50,000 0% 0% The mid segment continues to be the focus with a 62% share of the total unit launches during the quarter; translating to a q-o-q rise of 15% in absolute terms. -

Conference Report

26 th Annual Course in International Law Librarianship GLOBAL CHALLENGES & THE INDIAN LEGAL SYSTEM National Centre of Performing Arts, Mumbai 1st - 5th December 2007 International Association of Law Libraries by the inaugural address by the Hon’ble Mr. organized their 26 th Annual Course in Justice Y.V. Chandrachud, former Chief International Law Librarianship at National Justice of India. Centre of Performing Arts, Nariman Point, Mumbai, India between 1 st and 5 th December, 2007 . Folk and Bollywood Dances of India followed the address by the Hon’ble Chief Guest. The inaugural function was held on Saturday, 1 st December 2007 between 6 p.m. and 9 p.m. The Conference was inaugurated by Hon’ble Justice Y.V. Chandrachud, Former Chief Justice of India. Kala Parichaya group of Dr. Sandhya Purecha performed the Cultural programme. The function began with Indian Classical Dance followed by traditional Indian style of The academic sessions were held between lighting of lamp by the Hon’ble Justice Y.V. 2 December and 4 December 2007. The first Chandrachud, Mr. Jules Winterton, Mr. lecture of the academic session was Holger Knudsen and Mr. Halvor Kongshavn. delivered by Hon’ble Mr. Justice B.N. Srikrishna, former Judge, Supreme Court of India, on Introduction to Indian Legal System. The other speakers were Hon’ble Dr. Justice S.Radhakrishnan, Judge, Bombay High Court, Hon’ble Dr. Justice D.Y.Chandrachud Judge, Bombay High Court, Dr. Chandra Krishnamurthy, Vice Chancellor of S.N.D.T. The formal welcome address by Mr. Jules Women’s University, Ms. Flavia Agnes, Winterton, President of IALL was followed Lawyer and Women’s rights activist, Dr. -

CRAMPED for ROOM Mumbai’S Land Woes

CRAMPED FOR ROOM Mumbai’s land woes A PICTURE OF CONGESTION I n T h i s I s s u e The Brabourne Stadium, and in the background the Ambassador About a City Hotel, seen from atop the Hilton 2 Towers at Nariman Point. The story of Mumbai, its journey from seven sparsely inhabited islands to a thriving urban metropolis home to 14 million people, traced over a thousand years. Land Reclamation – Modes & Methods 12 A description of the various reclamation techniques COVER PAGE currently in use. Land Mafia In the absence of open maidans 16 in which to play, gully cricket Why land in Mumbai is more expensive than anywhere SUMAN SAURABH seems to have become Mumbai’s in the world. favourite sport. The Way Out 20 Where Mumbai is headed, a pointer to the future. PHOTOGRAPHS BY ARTICLES AND DESIGN BY AKSHAY VIJ THE GATEWAY OF INDIA, AND IN THE BACKGROUND BOMBAY PORT. About a City THE STORY OF MUMBAI Seven islands. Septuplets - seven unborn babies, waddling in a womb. A womb that we know more ordinarily as the Arabian Sea. Tied by a thin vestige of earth and rock – an umbilical cord of sorts – to the motherland. A kind mother. A cruel mother. A mother that has indulged as much as it has denied. A mother that has typically left the identity of the father in doubt. Like a whore. To speak of fathers who have fought for the right to sire: with each new pretender has come a new name. The babies have juggled many monikers, reflected in the schizophrenia the city seems to suffer from. -

India 2020 Crime & Safety Report: Mumbai

India 2020 Crime & Safety Report: Mumbai This is an annual report produced in conjunction with the Regional Security Office at the U.S. Consulate General in Mumbai. OSAC encourages travelers to use this report to gain baseline knowledge of security conditions in India. For more in-depth information, review OSAC’s India-specific webpage for original OSAC reporting, consular messages, and contact information, some of which may be available only to private-sector representatives with an OSAC password. Travel Advisory The current U.S. Department of State Travel Advisory at the date of this report’s publication assesses most of India at Level 2, indicating travelers should exercise increased caution due to crime and terrorism. Some areas have increased risk: do not travel to the state of Jammu and Kashmir (except the eastern Ladakh region and its capital, Leh) due to terrorism and civil unrest; and do not travel to within ten kilometers of the border with Pakistan due to the potential for armed conflict. Review OSAC’s report, Understanding the Consular Travel Advisory System Overall Crime and Safety Situation The Consulate represents the United States in Western India, including the states of Maharashtra, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, and Goa. Crime Threats The U.S. Department of State has assessed Mumbai as being a MEDIUM-threat location for crime directed at or affecting official U.S. government. Although it is a city with an estimated population of more than 25 million people, Mumbai remains relatively safe for expatriates. Being involved in a traffic accident remains more probable than being a victim of a crime, provided you practice good personal security. -

Section 124- Unpaid and Unclaimed Dividend

Sr No First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 ASHOK KUMAR GOLCHHA 305 ASHOKA CHAMBERS ADARSHNAGAR HYDERABAD 500063 0000000000B9A0011390 36.00 2 ADAMALI ABDULLABHOY 20, SUKEAS LANE, 3RD FLOOR, KOLKATA 700001 0000000000B9A0050954 150.00 3 AMAR MANOHAR MOTIWALA DR MOTIWALA'S CLINIC, SUNDARAM BUILDING VIKRAM SARABHAI MARG, OPP POLYTECHNIC AHMEDABAD 380015 0000000000B9A0102113 12.00 4 AMRATLAL BHAGWANDAS GANDHI 14 GULABPARK NEAR BASANT CINEMA CHEMBUR 400074 0000000000B9A0102806 30.00 5 ARVIND KUMAR DESAI H NO 2-1-563/2 NALLAKUNTA HYDERABAD 500044 0000000000B9A0106500 30.00 6 BIBISHAB S PATHAN 1005 DENA TOWER OPP ADUJAN PATIYA SURAT 395009 0000000000B9B0007570 144.00 7 BEENA DAVE 703 KRISHNA APT NEXT TO POISAR DEPOT OPP OUR LADY REMEDY SCHOOL S V ROAD, KANDIVILI (W) MUMBAI 400067 0000000000B9B0009430 30.00 8 BABULAL S LADHANI 9 ABDUL REHMAN STREET 3RD FLOOR ROOM NO 62 YUSUF BUILDING MUMBAI 400003 0000000000B9B0100587 30.00 9 BHAGWANDAS Z BAPHNA MAIN ROAD DAHANU DIST THANA W RLY MAHARASHTRA 401601 0000000000B9B0102431 48.00 10 BHARAT MOHANLAL VADALIA MAHADEVIA ROAD MANAVADAR GUJARAT 362630 0000000000B9B0103101 60.00 11 BHARATBHAI R PATEL 45 KRISHNA PARK SOC JASODA NAGAR RD NR GAUR NO KUVO PO GIDC VATVA AHMEDABAD 382445 0000000000B9B0103233 48.00 12 BHARATI PRAKASH HINDUJA 505 A NEEL KANTH 98 MARINE DRIVE P O BOX NO 2397 MUMBAI 400002 0000000000B9B0103411 60.00 13 BHASKAR SUBRAMANY FLAT NO 7 3RD FLOOR 41 SEA LAND CO OP HSG SOCIETY OPP HOTEL PRESIDENT CUFFE PARADE MUMBAI 400005 0000000000B9B0103985 96.00 14 BHASKER CHAMPAKLAL -

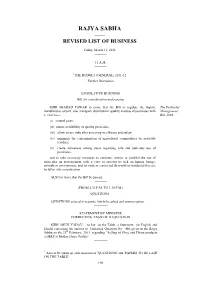

Rajya Sabha —— Revised List of Business

RAJYA SABHA —— REVISED LIST OF BUSINESS Friday, March 11, 2011 ——— 11 A.M. ——— ∗THE BUDGET (GENERAL) 2011-12 Further Discussion ——— LEGISLATIVE BUSINESS Bill for consideration and passing SHRI SHARAD PAWAR to move that the Bill to regulate the import, The Pesticides manufacture, export, sale, transport, distribution, quality and use of pesticides with Management a view to— Bill, 2008 (i) control pests; (ii) ensure availability of quality pesticides; (iii) allow its use only after assessing its efficacy and safety; (iv) minimize the contamination of agricultural commodities by pesticide residues; (v) create awareness among users regarding safe and judicious use of pesticides, and to take necessary measures to continue, restrict or prohibit the use of pesticides on reassessment with a view to prevent its risk on human beings, animals or environment, and for matters connected therewith or incidental thereto, be taken into consideration. ALSO to move that the Bill be passed. ——— (FROM 2.30 P.M. TO 3.30 P.M.) QUESTIONS QUESTIONS entered in separate lists to be asked and answers given. ———— STATEMENT BY MINISTER CORRECTING ANSWER TO QUESTION SHRI ARUN YADAV to lay on the Table, a Statement (in English and Hindi) correcting the answer to Unstarred Question No. 480 given in the Rajya Sabha on the 25th February, 2011, regarding “Selling of Ghee and Dhara products at MRP at Mother Dairy Outlets”. ———— ∗ Also to be taken up after disposal of 'QUESTIONS' and 'PAPERS TO BE LAID ON THE TABLE'. 108 PAPERS TO BE LAID ON THE TABLE Following Ministers to lay papers on the Table entered in the separate list: — 1. -

Introduction

Introduction Mumbai, is one of its 10 mega cities of the world and business capital of India. Mumbai proper occupies a low-lying area that once consisted of seven islands called Colaba, Mazagaon, Old Woman's Island, Wadala, Mahim, Parel, and Matunga-Sion separated from each other only during high tide. The population has risen from merely 3 millions in 1951 to 12 millions as on 2002 out of which 50 % live in slums It also supports “daily commuting” population of 20 lakhs It covers an area of 437 sq.km. With average density of 36600 soul/ sq.km. Water Supply-From Past To Present Prior to 1870, the Mumbaikar used to drink water from the existing well, lakes and tanks. But during middle of nineteenth century, because of the epidemic, decision was taken to build a dam to supply good quality of potable water, and then onwards Bombay water works started functioning The history of Mumbai’s water supply dates back to the 22nd June 1845. On this day, the then Government in response to the agitation of the native appointed 2 men Commission to report about the quality and quantity of water available in Mumbai. The Commission reported back within 24 hours that the water supply of Mumbai needed immediate attention. This was the beginning of efforts to search sources of water to satisfy the City’s demand. It is the first city in India to receive piped water supply in the year 1860. Today it supplies 2950 MLD every day, is one of the largest water supply in Asia. -

Sanjay Nirupam, 44

Do you know Who your MP is? SANJAY NiRUPAM Borivali Dahisar gURUDAS KanDivali MalaD kAMAt anDheri (e&w), GoreGaon, juhu, N joGeshwari (e&w), vile parle (w) NW NE PRiYA DUtt anDheri (e), BanDra (e&w), Chuna Bhati, Khar (e&w), Kurla, NC KherwaDi, tilaKnaGar, viDya vihar, SANJAY vile parle (e&w) DiNA santaCruz (e&w), SC PAtil BhanDup, CheMBur, WhAt GhatKopar, GovanDi, Kanjur MarG, KhinDi paDa DOES S ManKhurD, MulunD, troMBay, viDya vihar, AN MP viKhroli MiliND DEORA DO? ByCulla, MasjiD, Cst area, BunDer Charni rD, MazGaon, EkNAth gAikWAD ChinChpoKli, MuMBaDevi, ChurChGate, MuMBai Central, antop hill, MahiM, ColaBa, naGpaDa, CheMBur, MatunGa, Cotton Green, opera house, Chuna Bhati, nainGauM, Currey rD, parel, DaDar, parel, DoCKyarD rD, reay rD, Dharavi, praBhaDevi, elphinstone rD, sanDhurst rD, elphinstone sion, GirGauM, sewri, roaD, GovanDi, tilaK naGar, Grant roaD, tarDeo, GtB naGar, troMBay, KalBhaDevi Kh uMerKhaDi, KinG’s CirCle, waDala Marine lines, worli 2 3 mp profiles and to do’s areas promises performance public source performance self declared Corruption transport & infrastruCture stations ? ? quality ? ? sanjay nirupam, 44 ? INC, Mumbai North ? education: B.A. (Hons.), Political Science, A.N College, Patna employement history: Pancha Janya (Sub-Editor), Jan Satta, Dopahar Ka Samna (Executive Editor) health ? ? net assets: (Partially done) enviornment (Partially done) pending Court Cases: ? known to be defamatory ? ? ?