Bruno Schulz – Digitally. the Internet Gamebook Idol and the Future of Schulz Adaptations on the Computer Screen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flight from the Dark

Flight from the Dark Joe Dever Illustrated by Gary Chalk You are Lone Wolf. In a devastating attack the Darklords have destroyed the monastery where you were learning the skills of the Kai Lords. You are the sole survivor. In Flight from the Dark, you swear revenge. But first you must reach Holmgard to warn the King of the gathering evil. Relent- lessly the servants of darkness hunt you across your country and every turn of the page presents a new challenge. Choose your skills and your weapons carefully—for they can help you succeed in the most fantastic and terrifying journey of your life. Text copyright c 1984 Joe Dever. Illustrations copyright c 1984 Gary Chalk. Distribution of this Internet Edition is restricted under the terms of the Project Aon License. Publication Date: 10 May 2010 Internet Edition published by Project Aon. This edition is intended to reflect the complete text of the original version. Where we have made minor corrections, they will be noted in the Errata. This PDF was typeset with LATEX. To Mel and Yin Contents About the Author and Illustrator 9 Acknowledgements 11 The Story So Far . 13 The Game Rules 15 Kai Wisdom 29 Numbered Sections 31 Action Chart 200 Combat Rules Summary 203 Combat Results Table 204 Random Number Table 206 Errata 207 Project Aon License 211 Map of the Lastlands 216 About the Author and Illustrator Joe Dever, the creator of the bestselling Lone Wolf adven- ture books and novels, has achieved world-wide recognition in three creative fields—as an award-winning author of international renown, as an acclaimed musician and composer, and as a games designer specialising in role-playing games. -

Adventure Quest I Spent the Spring Break of My Junior Year of College

Adventure Quest I spent the spring break of my Junior year of college going through my basement. My mother had charged me with combing my things, throwing out everything I didn’t need and picking what I would take when my family moved to Atlanta, Georgia later the next month. In a box of old papers and binders from high school, I found a notebook containing one of the many “choose your own adventure” stories my best friend, Josh Saville, and I had written. Flipping through the pages it became clear to me what I wanted to spend the next year working on. Excited at my idea, I quickly told Josh of my plans, and he joined my excitement for our future project. That summer we began writing the original story that I would adapt into a choose-your-own-adventure-style comic book that would become Adventure Quest. Then, as well as now, my first interest when it comes to this project is branching storytelling. My first encounter with this type of narration, like many people, was with the classic Choose Your Own Adventure book series. As a child, the ability to have agency in the story in front of me was exhilarating. It wasn’t until later in High School that I, along with Josh, became fascinated with the underlying structure and framework of these stories as well as the unique possibilities second person narration gives to a work of prose. My second interest in this project is the problem of adapting prose in a visual way for a comic book. -

Immersion and Reading Comprehension: a Comparison of Reading from Print Or Video Game Text

Jacqueline Schaepman S1133330 Dr. Prof. P.A.F. Verhaar Master Thesis January 2020 Word count: 18025 Immersion and reading comprehension: a comparison of reading from print or video game text 0 Table of contents Abstract 2 Introduction 4 Chapter 1: Related literature and theoretical focus 8 1.1 Navigability 8 1.2 Immersion 11 1.3 Narrative 15 1.4 Reading Comprehension 17 1.5 Summary 18 Chapter 2: Methodology of the case study 20 Chapter 3: Research Results 29 3.1 Navigability in The Shamutanti Hills 31 3.2 Immersion in The Shamutanti Hills 32 3.3 Reading comprehension and reading speed 35 Chapter 4: Discussion 38 4.1 Navigability 39 4.2 Immersion 40 4.3 Narrative 40 4.4 Reading Comprehension 41 Chapter 5: Conclusion and Recommendations 41 Conclusion 42 Recommendations 42 Recommendations for methodology 42 Recommended areas for future research 43 Acknowledgment 44 References 44 Appendix 47 List of Figures 47 List of Tables 48 1 Abstract A study published in 2017 about leisure time use of average American citizens depicted the percentage of time Americans read, played video games or did other leisure activities on the computer.1 On an average day, only 21% of respondents in 2015 would read as a pastime, a decrease from the 27% of respondents that would read for pleasure in 2005. As opposed to this, the playing of video games as a pastime increased by 38%. With the preference of time use leaning towards gaming as well as the increasing popularity of smartphones and online devices, most people tend to spend more time reading from a screen rather than from print with the average adult spending around nine hours per day reading, swiping and listening to media.2 This, however, is claimed to crucially affect our level of text comprehension. -

Authoring RPG Gamebooks for Learning Game Writing and Design José P

Fighting Fantasies: Authoring RPG Gamebooks for Learning Game Writing and Design José P. Zagal & Corrinne Lewis Entertainment Arts & Engineering University of Utah 50 S. Central Campus Dr, RM 3190 Salt Lake City, UT 84112, USA [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT Students learning to design and write games face a diversity of challenges. For example, they might lack knowledge and experience in certain game types (Zagal and Bruckman 2007), or an understanding of fundamental components of narrative structure. In this article we describe an assignment we feel helps address some of these challenges. We have developed a gamebook writing assignment, specifically one using the Fighting Fantasy system (Jackson and Livingstone 1982), as a way to introduce students to game design, narrative and narrative construction in games, and how to think about non-linear storytelling. We argue that this assignment, which has been used successfully in multiple undergraduate and graduate classes, affords myriad learning opportunities including practice knitting story with game mechanics and an opportunity to gain a more nuanced understanding of how they interact and interrelate. Keywords Game education, fighting fantasy, gamebook, RPG gamebook INTRODUCTION While role-playing has been considered an important tool and technique for encouraging learning (e.g. Wohlking and Gill 1980; van Ments 1999), it seems to be used less often for learning about game design, interactive storytelling, or narrative development as it relates to games. We argue that role-playing gamebooks (RPG gamebooks) provide a unique set of affordances that can be used by instructors to help their students. For example, Newman (1988) described how using gamebooks was helpful for students planning their adventure game designs while Siddle and Platts (2011) argued they could be productive in supporting software design education. -

Where Stories End and Games Begin by Greg Costikyan

Story vs. Game 25.03.2003 10:16 Uhr Where Stories End and Games Begin by Greg Costikyan "Every medium has been used to tell stories," says Eric Goldberg, one of my oldest friends and president of Unplugged Games. "That's true of books and theater and radio drama and movies. It's true of games as well." I have this argument all the time, and I think Goldberg's statement is balderdash. It's not true of music; music is pleasing sound, that's all. Yes, you can tell a story with music; ballads do that. So do many pop songs . Certainly some types of music -- opera, ballet, the musical -- are "story-telling musical forms," but music itself is not a story-telling medium. The pleasure people derive from music is not dependent on its ability to tell stories: Tell me the story of The Brandenberg Concertoes. Nor is gaming a storytelling medium. The pleasure people derive from games is not dependent on their ability to tell stories. The idea that games have something to do with stories has such a hold on designers' and gamers' imagination that it probably can't be expunged, but it deserves at least to be challenged. Game designers need to understand that gaming is not inherently a storytelling medium any more than is music--and that this is not a flaw, that our field is not intrinsically inferior to, say, film, merely because movies are better at story-telling. Nevertheless, there are games that tell stories--roleplaying games and graphic adventures among others -- and the intersection of game and story, the places where the two (often awkwardly) meet has bred a wide variety of interesting game styles. -

Openned Zine #4

OPENNEDZINE OPENNED.COM 4 ISSUE © Openned January 2011 [email protected] web addresses, e-mail addresses and bold text are clickable hyper- links photo Joe Luna Image © Emily Critchley OPENNED NEWS THE WORKSHOP GREENWICH FESTIVAL H.E. PROTESTS Steven Fowler will be conducting PROJECT A record of information and a series of interviews with past Videos from summer 2010’s thoughts about the student pro- and present participants of Lon- Greenwich Festival, organised by tests that took place at the end of don’s Writers Forum workshop Emily Critchley and Carol 2010 around the UK is available over the next few months. The Watts, will be available to view to view on Openned here. resulting recordings will be very soon on Openned (it has hosted on Openned. Check out taken longer than anticipated to his article in this issue of the process the thousands of feet of Zine for more inform. film we took). Thank you to Emily and Carol for putting on this fantastic event. EDITORIAL Openned is based in welcome to the first issue London, UK, and is By Alex Davies & Steve Willey run by Stephen Willey and Alex Davies. The Openned Zine is setting out with one intention: to provide poets, Openned seeks to publishers and organisers with a space to publicly present explana- create flexible spaces for poetry and poetic tions, thoughts, ideas!and opinions that may not necessarily be repre- practitioners by invit- ing less established OPENNED.COM sentative of a final response. and more established writers to read to- The fourth issue of the Openned Zine is dedicated to gether, curating publi- cations, documenting exploring outside of the bubble. -

ERJ 3.2 Version8

1 SPECIAL ONLINE ISSUE: Contents Message from the Editor Page 2 Reading to Survive! – Task-based extensive reading for the de-motivated Page 3 Jake Arnold Using the Best-Selling Novel, Tuesdays with Morrie for Extensive Reading. Page 22 Mayumi Asaba Class Readers: The Learner’s Perspective Page 25 Rory Rosszell 2 Message from the Editor From time to time researchers submit articles which can not go in a standard issue of ERJ. Sometimes they are too long, or do not fit in well with the usual format. This is a problem as they are often articles which would be of interest to the readers of ERJ. To rectify this situation, we are releasing this Special Edition of ERJ containing three such articles. In the future, we plan to release one Special Issue of ERJ each year to give researchers a place to publish worthy articles, that we would otherwise not be able to publish. The lead article by Jake Arnold discusses Gamebooks and includes a 14 page sample chapter which we would not have been able to include is a regular edition of ERJ because of the length. If you have any questions or advice for Jake Arnold, please contact him at <[email protected]>. Mayumi Asaba’s article describing using Tuesdays with Morrie with her students could be considered by some to be intensive reading rather than extensive reading. Her article is included here as it shows the potential strength of using a class reader. Rory Rosszell also deals with the class reader issue and brings in the opinions of the most important people - the students. -

Level and Story Design in Choose Your Own Adventure Games 4 Pages of Appendices Commissioned By

Sirja Lyömiö LEVEL AND STORY DESIGN IN CHOOSE YOUR OWN ADVENTURE GAMES Bachelor‘s thesis Degree Programme in Design 2017 Tekijä/Tekijät Tutkinto Aika Sirja Lyömiö Muotoilija Toukokuu 2017 Opinnäytetyön nimi 79 sivua Kenttä- ja tarinasuunnittelu tekstiseikkailupeleissä 4 liitesivua Toimeksiantaja - Ohjaaja Marko Siitonen, tuntiopettaja Tiivistelmä Tämä tutkimus keskittyi tekstiseikkailupeleihin. Sen aikana tutkittiin seikkailupelien tärkeimpiä rakenteita ja pelimekaniikkoja. Samalla hahmottui, mitä kaikkea pitää ottaa huomioon haarautuvaa tarinaa kirjoittettaessa ja tekstiseikkailua rakennettaessa. Tämän tutkimuksen toivotaan olevan hyödyllinen apuväline kaikille tästä kyseisestä pelityypistä kiinnostuneille, jotka aikovat kirjoittaa oman tarinan. Tekstiseikkailuja tutkittiin muutaman olemassaolevan esimerkin kautta (Colossal Cave Adventure, Fighting Fantasy: The Warlock of Firetop Mountain, 80 Days), jotta saataisiin parempi käsitys siitä, mitkä ovat näiden pelien ydinrakenteet ja miten ne näkyvät pelien aikana sekä niiden tarinassa. Näitä rakenteita tutkittiin peleissä esiintyvien esimerkkien kautta. Tutkimus esitteli myös muutaman ilmaisen työkalun tekstiseikkailuiden kirjoittamista varten. Niistä esiteltiin perustoiminta, sekä mitä vaihtoehtoja ne tarjoavat tarinan kirjoittajalle pelitoimintojen suhteen. Yksi esitellyistä työkaluista (Inklewriter) valittiin tämän tutkimuksen ohella kirjoitetun A Day in Tumbleweed -tarinan kirjoitusalustaksi. Tarinan kirjoitusprosessi sekä aikataulu esiteltiin, jotta ne tarjoaisivat lisätietoa kaikista -

Children's Books by Bulgarian Writers and Artists

Children’s Books by Bulgarian Writers and Artists 1 Проектът е реализиран с финансовата подкрепа на Национален фонд Култура. 2016 2017 Children’s Books by Bulgarian Writers and Artists Children’s Books by Bulgarian Writers and Artists © National Palace of Culture – Congress Centre Sofia 2019, National Book Centre © Translation by Angela Rodel, Dessyslava Nikolova, Dessyslava Toncheva © Angel Mitev, preface Svetlozar Zhelev, editor Angela Rodel, Proofreading and editing © Damyan Damyanov, cover and book design Dear publishers and friends of Bulgarian literature, You are holding in your hands the new catalogue containing the most interesting, im- portant and notable children’s books produced over the past year by Bulgarian writers and artists. Through children’s books we can understand much about a people, a country and a culture. The purity’s of a child’s mind, the path towards it, the way we unite it with the values and the spirit of our society and our times – all of this allows us to touch the most authentic, sincere and transparent essence of a nation, its past, present and future. The National Book Centre and the National Palace of Culture for the third year in a row present to you these magical works of art, which represent the talents and achievements of Bulgarian writers and artists in their noble mission to engage children’s minds and to win them over to the knowledge, goodness and light of literature. Children are the most critical, least burdened and most fragile readers. Thus, to reach them, both writers and artists must put their whole heart and soul into their work. -

Life and Death in the Second Person: Identification, Empathy And

Life and death in the second person: Identification, empathy and antipathy in the gamebook Dr Paul Wake Manchester Metropolitan University [email protected] Abstract This essay argues that the second-person address of the interactive gamebook generates a mode of identification between reader (player) and character that functions not through immersion or presence but through an estranging logic that arises from the particular affordances of the print form. It begins by situating the gamebook, an influential but short-lived genre that enjoyed its heyday in the 1980s and early 1990s, in relation to other forms of second-person narrative as well as Interactive Fiction and video games, before turning to a consideration of the points at which the forms diverge. Taking Steve Jackson and Ian Livingstone’s The Warlock of Firetop Mountain (1982) as its example, the essay then examines the ways in which the gamebook’s highly-demanding print form undermines notions of transparency, arguing that identification with the gamebook you is specific to, and reliant upon, the material properties of the print text. 1 Keywords: empathy; gamebook; hypertext; immersion; interactive fiction; fantasy fiction; presence; second person narrative Life and death in the second person: Identification, empathy and antipathy in the gamebook 2 Fig. “The locked door bursts open.” Image © 1982 Russ Nicholson. The locked door bursts open and a nauseating stench hits your nostrils. Inside the room the floor is covered with bones, rotting vegetation and slime. A wild-haired old man, clothed in rags, rushes at you screaming. His beard is long and grey, and he is waving an old wooden chair-leg. -

Children's Books from Bulgaria: Contemporary Writers and Artists

Children’s Books from Bulgaria: Contemporary Writers and Artists 1 Children’s Books from Bulgaria Books from Children’s Проектът е реализиран с финансовата подкрепа на Национален фонд Култура. 2 This project was realized with the support of the Culture National Fund. Children’s Books from Bulgaria Books from Children’s Children’s Books from Bulgaria: Contemporary Writers and Artists © National Palace of Culture – Congress Centre Sofia 2016, National Book Centre © Svetlana Stoicheva, preface Valentina Stoeva, editor Angela Rodel, Proofreading and editing © Damyan Damyanov, cover and book design 3 Children’s Books from Bulgaria: Children’s Books from Bulgaria Books from Children’s Contemporary Writers and Artists 4 Children’s Books from Bulgaria Books from Children’s 5 Dear publishers, readers and future friends of Bulgarian literature, It is my pleasure to present to you a catalogue of contemporary Bulgarian children books, containing the most established Bulgarian authors and artists and their most interesting works. This collection represents a cross-section of what is happening in the field of Bulgarian children’s literature at the moment. Without claiming completeness or exhaustiveness, we have tried to present to you a representative sample of the most interesting books and authors over the last seven years; this edition lays the foundations for such an annual catalogue to be published by the National Book Center at the National Palace of Culture (NDK), which from now on Children’s Books from Bulgaria Books from Children’s will include books published within a given literary year. Although over the years attempts have been made in this direction, I believe that for the first time through this catalogue, readers abroad can get a sufficiently full impression of the art of children’s books in Bulgaria, of our best authors, and of the exceptionally high level Bulgarian children’s books has reached in recent years. -

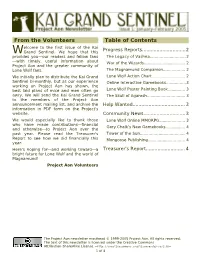

January 2005

From the Volunteers Table of Contents elcome to the first issue of the Kai Progress Reports..............................2 WGrand Sentinel. We hope that this provides you—our readers and fellow fans The Legacy of Vashna............................. 2 —with timely, useful information about War of the Wizards................................. 2 Project Aon and the greater community of Lone Wolf fans. The Magnamund Companion.................. 2 We initially plan to distribute the Kai Grand Lone Wolf Action Chart........................... 2 Sentinel bi-monthly, but as our experience Online Interactive Gamebooks................3 working on Project Aon has shown, the best laid plans of mice and men often go Lone Wolf Poster Painting Book.............. 3 awry. We will send the Kai Grand Sentinel The Skull of Agarash............................... 3 to the members of the Project Aon announcement mailing list, and archive the Help Wanted.................................... 3 information in PDF form on the Project's website. Community News.............................3 We would especially like to thank those Lone Wolf Online MMORPG..................... 3 who have made contributions—financial Gary Chalk's New Gamebooks................ 4 and otherwise—to Project Aon over the past year. Please read the Treasurer's Tower of the Sun.................................... 4 Report to see how we did financially this Mongoose Publishing.............................. 4 year. Here's hoping for—and working toward—a Treasurer's Report........................... 4 bright future for Lone Wolf and the world of Magnamund! Project Aon Volunteers The Project Aon newsletter masthead © 1999-2005 Project Aon. All rights reserved. The text of this newsletter is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License. <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/> 1 of 4 Progress Reports contacted and has given his permission for Project Aon to use his work.