Pivoting the Player

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Steve Jackson

It Takes A Thief. When brute force won’t get the job done, you need someone with . skills. A specialist. Preferably someone who doesn’t let a lot of nagging concerns a b out law or morality get in the way. Whether you’re looking for just the right character to GURPS Basic Set, Third Edi- round out an adventuring party, or a dangerous NPC to tion Revised and GURPS challenge your players, GURPS Rogues has what Compendium I are required to use this book in a GURPS you need – 29 different templates, letting you quickly campaign. While designed create the scoundrel that’s right for the job. for the GURPS system, the Templates include . character archetypes and ! Thieves who are only in it for the money, such as the sample characters in this armed robber, cat burglar, pirate, pickpocket, house- book can be used in any roleplaying setting. breaker, and forger. ! Rogues who have other goals than mere material THE ROGUES’ GALLERY: gain, like the spy, hacker, evil mastermind, mad scientist, and saboteur. Written by Lynette Cowper ! Charmers who work more with people’s minds than with lockpicks and prybars, . the con man, bard, Edited by fixer, gambler, prostitute, and street doctor. Solomon Davidoff ! Mysterious figures who work on the shadowy edges and Scott Haring of society – the tracker, poacher, assassin, Cover by m aster thief, smuggler, mobster, and black marketeer. Ed Cox Each template comes with four complete characters, Illustrated by drawn from a wide range of settings. All told, you Andy B. Clarkson, get 116 ready-to-use sample characters, as well as his- Jeremy McHugh, torical background and information on the Thomas Floyd, Cob Carlos, Bob Cram, t e chnology and tactics that shaped their professions. -

Investor Briefing

Q4 2019 AT&T EARNINGS Investor Briefing No. 307 | JANUARY 29, 2020 INVESTOR BRIEFING Q4 2019 AT&T EARNINGS Contents 3 Communications Mobility Entertainment Group Business Wireline 7 WarnerMedia Turner Home Box Office Warner Bros. 10 Latin America Mexico Vrio 11 Xandr 13 Financial and Operational Information 28 Discussion and Reconciliation of Non-GAAP Measures INVESTOR BRIEFING Q4 2019 AT&T EARNINGS Communications FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS Nj $36.5 billion, down 1.9% year over year due to declines in Entertainment Group and Business Revenues Wireline that were partially offset by gains in wireless service revenues Nj $29.0 billion, down 2.0% year over year, reflecting lower Entertainment Group and Business Operating Expenses Wireline expenses partially offset by increases in Mobility expenses Nj $7.5 billion, down 1.2% year over year; operating income margin of 20.6% compared to Operating Income 20.4% in the year-ago quarter MOBILITY Nj $18.7 billion, up 0.8% year over year due to an increase in service revenues offsetting declines in equipment revenues ■ Service revenues: $13.9 billion, up 1.8% year over year due to prepaid subscriber gains Revenues and postpaid phone ARPU growth ■ Equipment revenues: $4.8 billion, down 2.1% year over year with continued low postpaid phone upgrade rates Nj $13.2 billion, up 0.5% year over year due to higher bad debt, promotions and advertising Operating Expenses expenses partially offset by lower equipment costs and cost efficiencies Nj $5.5 billion, up 1.5% year over year; operating income margin of 29.4%, compared -

III. Here Be Dragons: the (Pre)History of the Adventure Game

III. Here Be Dragons: the (pre)history of the adventure game The past is like a broken mirror, as you piece it together you cut yourself. Your image keeps shifting and you change with it. MAX PAYNE 2: THE FALL OF MAX PAYNE At the end of the Middle Ages, Europe’s thousand year sleep – or perhaps thousand year germination – between antiquity and the Renaissance, wondrous things were happening. High culture, long dormant, began to stir again. The spirit of adventure grew once more in the human breast. Great cathedrals rose, the spirit captured in stone, embodiments of the human quest for understanding. But there were other cathedrals, cathedrals of the mind, that also embodied that quest for the unknown. They were maps, like the fantastic, and often fanciful, Mappa Mundi – the map of everything, of the known world, whose edges both beckoned us towards the unknown, and cautioned us with their marginalia – “Here be dragons.” (Bradbury & Seymour, 1997, p. 1357)1 At the start of the twenty-first century, the exploration of our own planet has been more or less completed2. When we want to experience the thrill, enchantment and dangers of past voyages of discovery we now have to rely on books, films and theme parks. Or we play a game on our computer, preferably an adventure game, as the experience these games create is very close to what the original adventurers must have felt. In games of this genre, especially the older type adventure games, the gamer also enters an unknown labyrinthine space which she has to map step by step, unaware of the dragons that might be lurking in its dark recesses. -

Conan O'brien

Second Place Stars presents… The O’Brien Hourly Bonus 1 Perhaps you know him from his show on TBS or perhaps you have been a devout follower since the days of Late Night with Conan O’Brien. Or maybe you have no idea who this red- headed person in a suit is (in which case, I pity you). Either way, test your knowledge of Conan and the various late night shows he has been affiliated with. Even if you don’t know a single thing about Conan, there may be some questions you may still know the answer to. The number in the brackets at the end of the question represents how many points each question is worth. But in the end, your answers will be graded on a 15 point scale if you don’t use the internet or a 10 point scale if you do use the internet. Good luck! 1. Before becoming the host for Late Night, Conan was a writer for The Simpsons. This episode, written by Conan O’Brien, had a guest appearance by Leonard Nimoy. [1] 2. Before either she or Conan was married or famous and before she played a New York City masseuse or a web therapist, this actress was reportedly more than just “friends” with her fellow Groundling. [1] Several other famous actors had their start on Late Night with Conan O’Brien either as interns or actors. Most of them are still affiliated with the peacock network particularly by its Thursday night comedy line up. Who knew watching television would come in handy one day? 3. -

Nordic Game Is a Great Way to Do This

2 Igloos inc. / Carcajou Games / Triple Boris 2 Igloos is the result of a joint venture between Carcajou Games and Triple Boris. We decided to use the complementary strengths of both studios to create the best team needed to create this project. Once a Tale reimagines the classic tale Hansel & Gretel, with a twist. As you explore the magical forest you will discover that it is inhabited by many characters from other tales as well. Using real handmade puppets and real miniature terrains which are then 3D scanned to create a palpable, fantastic world, we are making an experience that blurs the line between video game and stop motion animated film. With a great story and stunning visuals, we want to create something truly special. Having just finished our prototype this spring, we have already been finalists for the Ubisoft Indie Serie and the Eidos Innovation Program. We want to validate our concept with the European market and Nordic Game is a great way to do this. We are looking for Publishers that yearn for great stories and games that have a deeper meaning. 2Dogs Games Ltd. Destiny’s Sword is a broad-appeal Living-Narrative Graphic Adventure where every choice matters. Players lead a squad of intergalactic peacekeepers, navigating the fallout of war and life under extreme circumstances, while exploring a breath-taking and immersive world of living, breathing, hand-painted artwork. Destiny’s Sword is filled with endless choices and unlimited possibilities—we’re taking interactive storytelling to new heights with our proprietary Insight Engine AI technology. This intricate psychology simulation provides every character with a diverse personality, backstory and desires, allowing them to respond and develop in an incredibly human fashion—generating remarkable player engagement and emotional investment, while ensuring that every playthrough is unique. -

DESIGN-DRIVEN APPROACHES TOWARD MORE EXPRESSIVE STORYGAMES a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of the Requirements for the Degree Of

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ CHANGEFUL TALES: DESIGN-DRIVEN APPROACHES TOWARD MORE EXPRESSIVE STORYGAMES A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in COMPUTER SCIENCE by Aaron A. Reed June 2017 The Dissertation of Aaron A. Reed is approved: Noah Wardrip-Fruin, Chair Michael Mateas Michael Chemers Dean Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright c by Aaron A. Reed 2017 Table of Contents List of Figures viii List of Tables xii Abstract xiii Acknowledgments xv Introduction 1 1 Framework 15 1.1 Vocabulary . 15 1.1.1 Foundational terms . 15 1.1.2 Storygames . 18 1.1.2.1 Adventure as prototypical storygame . 19 1.1.2.2 What Isn't a Storygame? . 21 1.1.3 Expressive Input . 24 1.1.4 Why Fiction? . 27 1.2 A Framework for Storygame Discussion . 30 1.2.1 The Slipperiness of Genre . 30 1.2.2 Inputs, Events, and Actions . 31 1.2.3 Mechanics and Dynamics . 32 1.2.4 Operational Logics . 33 1.2.5 Narrative Mechanics . 34 1.2.6 Narrative Logics . 36 1.2.7 The Choice Graph: A Standard Narrative Logic . 38 2 The Adventure Game: An Existing Storygame Mode 44 2.1 Definition . 46 2.2 Eureka Stories . 56 2.3 The Adventure Triangle and its Flaws . 60 2.3.1 Instability . 65 iii 2.4 Blue Lacuna ................................. 66 2.5 Three Design Solutions . 69 2.5.1 The Witness ............................. 70 2.5.2 Firewatch ............................... 78 2.5.3 Her Story ............................... 86 2.6 A Technological Fix? . -

Understanding Visual Novel As Artwork of Visual Communication Design

MUDRA Journal of Art and Culture Volume 32 Nomor 3, September 2017 292-298 P-ISSN 0854-3461, E-ISSN 2541-0407 Understanding Visual Novel as Artwork of Visual Communication Design DENDI PRATAMA, WINNY GUNARTI W.W, TAUFIQ AKBAR Departement of Visual Communication Design, Fakulty of Language and Art Indraprasta PGRI. University, Jakarta Selatan, Indonesia [email protected] Visual Novel adalah sejenis permainan audiovisual yang menawarkan kekuatan visual melalui narasi dan karakter visual. Data dari komunitas pengembang Visual Novel (VN) Project Indonesia menunjukkan masih terbatasnya pengembang game lokal yang memproduksi Visual Novel Indonesia. Selain itu, produksi Visual Novel Indonesia juga lebih banyak dipengaruhi oleh gaya anime dan manga dari Jepang. Padahal Visual Novel adalah bagian dari produk industri kreatif yang potensial. Studi ini merumuskan masalah, bagaimana memahami Visual Novel sebagai karya seni desain komunikasi visual, khususnya di kalangan mahasiswa? Penelitian ini merupakan studi kasus yang dilakukan terhadap mahasiswa desain komunikasi visual di lingkungan Universitas Indraprasta PGRI Jakarta. Hasil penelitian menunjukkan masih rendahnya tingkat pengetahuan, pemahaman, dan pengalaman terhadap permainan Visual Novel, yaitu di bawah 50%. Metode kombinasi kualitatif dan kuantitatif dengan pendekatan semiotika struktural digunakan untuk menjabarkan elemen desain dan susunan tanda yang terdapat pada Visual Novel. Penelitian ini dapat menjadi referensi ilmiah untuk lebih mengenalkan dan mendorong pemahaman tentang Visual Novel sebagai karya seni Desain Komunikasi Visual. Selain itu, hasil penelitian dapat menambah pengetahuan masyarakat, dan mendorong pengembangan karya seni Visual Novel yang mencerminkan budaya Indonesia. Kata kunci: Visual novel, karya seni, desain komunikasi visual Visual Novel is a kind of audiovisual game that offers visual strength through the narrative and visual characters. -

In- and Out-Of-Character

Florida State University Libraries 2016 In- and Out-of-Character: The Digital Literacy Practices and Emergent Information Worlds of Active Role-Players in a New Massively Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Game Jonathan Michael Hollister Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMUNICATION & INFORMATION IN- AND OUT-OF-CHARACTER: THE DIGITAL LITERACY PRACTICES AND EMERGENT INFORMATION WORLDS OF ACTIVE ROLE-PLAYERS IN A NEW MASSIVELY MULTIPLAYER ONLINE ROLE-PLAYING GAME By JONATHAN M. HOLLISTER A Dissertation submitted to the School of Information in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2016 Jonathan M. Hollister defended this dissertation on March 28, 2016. The members of the supervisory committee were: Don Latham Professor Directing Dissertation Vanessa Dennen University Representative Gary Burnett Committee Member Shuyuan Mary Ho Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For Grandpa Robert and Grandma Aggie. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thank you to my committee, for their infinite wisdom, sense of humor, and patience. Don has my eternal gratitude for being the best dissertation committee chair, mentor, and co- author out there—thank you for being my friend, too. Thanks to Shuyuan and Vanessa for their moral support and encouragement. I could not have asked for a better group of scholars (and people) to be on my committee. Thanks to the other members of 3 J’s and a G, Julia and Gary, for many great discussions about theory over many delectable beers. -

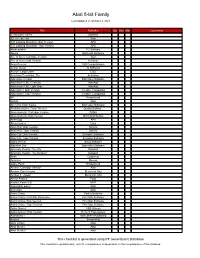

Atari 8-Bit Family

Atari 8-bit Family Last Updated on October 2, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments 221B Baker Street Datasoft 3D Tic-Tac-Toe Atari 747 Landing Simulator: Disk Version APX 747 Landing Simulator: Tape Version APX Abracadabra TG Software Abuse Softsmith Software Ace of Aces: Cartridge Version Atari Ace of Aces: Disk Version Accolade Acey-Deucey L&S Computerware Action Quest JV Software Action!: Large Label OSS Activision Decathlon, The Activision Adventure Creator Spinnaker Software Adventure II XE: Charcoal AtariAge Adventure II XE: Light Gray AtariAge Adventure!: Disk Version Creative Computing Adventure!: Tape Version Creative Computing AE Broderbund Airball Atari Alf in the Color Caves Spinnaker Software Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves Quality Software Alien Ambush: Cartridge Version DANA Alien Ambush: Disk Version Micro Distributors Alien Egg APX Alien Garden Epyx Alien Hell: Disk Version Syncro Alien Hell: Tape Version Syncro Alley Cat: Disk Version Synapse Software Alley Cat: Tape Version Synapse Software Alpha Shield Sirius Software Alphabet Zoo Spinnaker Software Alternate Reality: The City Datasoft Alternate Reality: The Dungeon Datasoft Ankh Datamost Anteater Romox Apple Panic Broderbund Archon: Cartridge Version Atari Archon: Disk Version Electronic Arts Archon II - Adept Electronic Arts Armor Assault Epyx Assault Force 3-D MPP Assembler Editor Atari Asteroids Atari Astro Chase Parker Brothers Astro Chase: First Star Rerelease First Star Software Astro Chase: Disk Version First Star Software Astro Chase: Tape Version First Star Software Astro-Grover CBS Games Astro-Grover: Disk Version Hi-Tech Expressions Astronomy I Main Street Publishing Asylum ScreenPlay Atari LOGO Atari Atari Music I Atari Atari Music II Atari This checklist is generated using RF Generation's Database This checklist is updated daily, and it's completeness is dependent on the completeness of the database. -

Computer Gaming World Issue

VOL. 2 NO. 2 MAR. - APR. 1982 Features SOUTHERN COMMAND 6 Review of SSI's Yom Kippur Wargame Bob Proctor SO YOU WANT TO WRITE A COMPUTER GAME 10 Advice on Game Designing Chris Crawford NAPOLEON'S CAMPAIGNS 1813 & 1815: SOME NOTES 12 Player's, Designer's, and Strategy Notes Joie Billings SO YOU WANT TO WIN A MILLION 16 Analysis of Hayden's Blackjack Master Richard McGrath ESCAPE FROM WOLFENSTEIN 18 Short Stay Based on the Popular Game Ed Curtis ODE TO JOY, PADDLE AND PORT: 19 Some Components for Game Playing Luther Shaw THE CURRENT STATE OF 21 COMPUTER GAME DOCUMENTATION Steve Rasnic Tern NORDEN+, ROBOT KILLER 25 Winner of CGW's Robotwar Tournament Richard Fowell TIGERS IN THE SNOW: A REVIEW 30 Richard Charles Karr YOU TOO CAN BE AN ACE 32 Ground School for the A2-FS1 Flight Simulator Bob Proctor BUG ATTACK: A REVIEW 34 Cavalier's New Arcade Game Analyzed Dave Jones PINBALL MANIA 35 Review of David's Midnight Magic Stanley Greenlaw Departments From the Editor 2 Hobby & Industry News 2 Initial Comments 3 Letters 3 The Silicon Cerebrum 27 Micro Reviews 36 Reader's Input Device 40 From the Editor... Each issue of CGW brings the magazine closer Input Device". Not only will it help us to know just to the format we plan to achieve. This issue (our what you want to read, it will also let the man- third) is expanded to forty pages. Future issues ufacturers know just what you think about the will be larger still. games on the market. -

Towards Collection Interfaces for Digital Game Objects

“The Collecting Itself Feels Good”: Towards Collection Interfaces for Digital Game Objects Zachary O. Toups,1 Nicole K. Crenshaw,2 Rina R. Wehbe,3 Gustavo F. Tondello,3 Lennart E. Nacke3 1Play & Interactive Experiences for Learning Lab, Dept. Computer Science, New Mexico State University 2Donald Bren School of Information and Computer Sciences, University of California, Irvine 3HCI Games Group, Games Institute, University of Waterloo [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Figure 1. Sample favorite digital game objects collected by respondents, one for each code from the developed coding manual (except MISCELLANEOUS). While we did not collect media from participants, we identified representative images0 for some responses. From left to right: CHARACTER: characters from Suikoden II [G14], collected by P153; CRITTER: P32 reports collecting Arnabus the Fairy Rabbit from Dota 2 [G19]; GEAR: P55 favorited the Gjallerhorn rocket launcher from Destiny [G10]; INFORMATION: P44 reports Dragon Age: Inquisition [G5] codex cards; SKIN: P66’s favorite object is the Cauldron of Xahryx skin for Dota 2 [G19]; VEHICLE: a Jansen Carbon X12 car from Burnout Paradise [G11] from P53; RARE: a Hearthstone [G8] gold card from the Druid deck [P23]; COLLECTIBLE: World of Warcraft [G6] mount collection interface [P7, P65, P80, P105, P164, P185, P206]. ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION Digital games offer a variety of collectible objects. We inves- People collect objects for many reasons, such as filling a per- tigate players’ collecting behaviors in digital games to deter- sonal void, striving for a sense of completion, or creating a mine what digital game objects players enjoyed collecting and sense of order [8,22,29,34]. -

Realistic Dialogue Engine for Video Games

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 1-5-2014 12:00 AM Realistic Dialogue Engine for Video Games Caroline M. Rose The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Mike Katchabaw The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Computer Science A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Science © Caroline M. Rose 2014 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Artificial Intelligence and Robotics Commons Recommended Citation Rose, Caroline M., "Realistic Dialogue Engine for Video Games" (2014). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 2652. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/2652 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REALISTIC DIALOGUE ENGINE FOR VIDEO GAMES (Thesis format: Monograph) by Caroline M. Rose Graduate Program in Computer Science A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Caroline M. Rose 2015 Abstract The concept of believable agent has a long history in Artificial Intelligence. It has applicability in multiple fields, particularly video games. Video games have shown tremendous technological advancement in several areas such as graphics and music; however, techniques used to simulate dialogue are still quite outdated. In this thesis, a method is proposed to allow a human player to interact with non-player characters using natural-language input.