PNW Gencyber Summer Camp: Game Based Cybersecurity Education for High School Students

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Une Bibliographie Commentée En Temps Réel : L'art De La Performance

Une bibliographie commentée en temps réel : l’art de la performance au Québec et au Canada An Annotated Bibliography in Real Time : Performance Art in Quebec and Canada 2019 3e édition | 3rd Edition Barbara Clausen, Jade Boivin, Emmanuelle Choquette Éditions Artexte Dépôt légal, novembre 2019 Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec Bibliothèque et Archives du Canada. ISBN : 978-2-923045-36-8 i Résumé | Abstract 2017 I. UNE BIBLIOGraPHIE COMMENTÉE 351 Volet III 1.11– 15.12. 2017 I. AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGraPHY Lire la performance. Une exposition (1914-2019) de recherche et une série de discussions et de projections A B C D E F G H I Part III 1.11– 15.12. 2017 Reading Performance. A Research J K L M N O P Q R Exhibition and a Series of Discussions and Screenings S T U V W X Y Z Artexte, Montréal 321 Sites Web | Websites Geneviève Marcil 368 Des écrits sur la performance à la II. DOCUMENTATION 2015 | 2017 | 2019 performativité de l’écrit 369 From Writings on Performance to 2015 Writing as Performance Barbara Clausen. Emmanuelle Choquette 325 Discours en mouvement 370 Lieux et espaces de la recherche 328 Discourse in Motion 371 Research: Sites and Spaces 331 Volet I 30.4. – 20.6.2015 | Volet II 3.9 – Jade Boivin 24.10.201 372 La vidéo comme lieu Une bibliographie commentée en d’une mise en récit de soi temps réel : l’art de la performance au 374 Narrative of the Self in Video Art Québec et au Canada. Une exposition et une série de 2019 conférences Part I 30.4. -

Catalogo-Festivaldorio-2015.Pdf

Sumário TABLE OF CONTENTS 012 APRESENTAÇÃO PRESENTATION 023 GALA DE ABERTURA OPENNING NIGHT GALA 025 GALA DE ENCERRAMENTO CLOSING NIGHT GALA 033 PREMIERE BRASIL PREMIERE BRASIL 079 PANORAMA GRANDES MESTRES PANORAMA: MASTERS 099 PANORAMA DO CINEMA MUNDIAL WORLD PANORAMA 2015 141 EXPECTATIVA 2015 EXPECTATIONS 2015 193 PREMIERE LATINA LATIN PREMIERE 213 MIDNIGHT MOVIES MIDNIGHT MOVIES 229 MIDNIGHT DOCS MIDNIGHT DOCS 245 FILME DOC FILM DOC 251 ITINERÁRIOS ÚNICOS UNIQUE ITINERARIES 267 FRONTEIRAS FRONTIERS 283 MEIO AMBIENTE THREATENED ENVIRONMENT 293 MOSTRA GERAÇÃO GENERATION 303 ORSON WELLS IN RIO ORSON WELLS IN RIO 317 STUDIO GHIBLI - A LOUCURA E OS SONHOS STUDIO GHIBLI - THE MADNESS AND THE DREAMS 329 LIÇÃO DE CINEMA COM HAL HARTLEY CINEMA LESSON WITH HAL HARTLEY 333 NOIR MEXICANO MEXICAN FILM NOIR 343 PERSONALIDADE FIPRESCI LATINO-AMERICANA DO ANO FIPRESCI’S LATIN AMERICAN PERSONALITY OF THE YEAR 349 PRÊMIO FELIX FELIX AWARD 357 HOMENAGEM A JYTTE JENSEN A TRIBUTE TO JYTTE JENSEN 361 FOX SEARCHLIGHT 20 ANOS FOX SEARCHLIGHT 20 YEARS 365 JÚRIS JURIES 369 CINE ENCONTRO CINE CHAT 373 RIOMARKET RIOMARKET 377 A ETERNA MAGIA DO CINEMA THE ETERNAL MAGIC OF CINEMA 383 PARCEIROS PARTNERS AND SUPPLIES 399 CRÉDITOS E AGRADECIMENTOS CREDITS AND AKNOWLEDGEMENTS 415 ÍNDICES INDEX CARIOCA DE CORPO E ALMA CARIOCA BODY AND SOUL Cidade que provoca encantamento ao olhar, o Rio Enchanting to look at, Rio de Janeiro will once de Janeiro estará mais uma vez no primeiro plano again take centre stage in world cinema do cinema mundial entre os dias 1º e 14 de ou- between the 1st and 14th of October. -

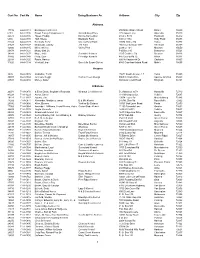

Cert No Name Doing Business As Address City Zip 1 Cust No

Cust No Cert No Name Doing Business As Address City Zip Alabama 17732 64-A-0118 Barking Acres Kennel 250 Naftel Ramer Road Ramer 36069 6181 64-A-0136 Brown Family Enterprises Llc Grandbabies Place 125 Aspen Lane Odenville 35120 22373 64-A-0146 Hayes, Freddy Kanine Konnection 6160 C R 19 Piedmont 36272 6394 64-A-0138 Huff, Shelia Blackjack Farm 630 Cr 1754 Holly Pond 35083 22343 64-A-0128 Kennedy, Terry Creeks Bend Farm 29874 Mckee Rd Toney 35773 21527 64-A-0127 Mcdonald, Johnny J M Farm 166 County Road 1073 Vinemont 35179 42800 64-A-0145 Miller, Shirley Valley Pets 2338 Cr 164 Moulton 35650 20878 64-A-0121 Mossy Oak Llc P O Box 310 Bessemer 35021 34248 64-A-0137 Moye, Anita Sunshine Kennels 1515 Crabtree Rd Brewton 36426 37802 64-A-0140 Portz, Stan Pineridge Kennels 445 County Rd 72 Ariton 36311 22398 64-A-0125 Rawls, Harvey 600 Hollingsworth Dr Gadsden 35905 31826 64-A-0134 Verstuyft, Inge Sweet As Sugar Gliders 4580 Copeland Island Road Mobile 36695 Arizona 3826 86-A-0076 Al-Saihati, Terrill 15672 South Avenue 1 E Yuma 85365 36807 86-A-0082 Johnson, Peggi Cactus Creek Design 5065 N. Main Drive Apache Junction 85220 23591 86-A-0080 Morley, Arden 860 Quail Crest Road Kingman 86401 Arkansas 20074 71-A-0870 & Ellen Davis, Stephanie Reynolds Wharton Creek Kennel 512 Madison 3373 Huntsville 72740 43224 71-A-1229 Aaron, Cheryl 118 Windspeak Ln. Yellville 72687 19128 71-A-1187 Adams, Jim 13034 Laure Rd Mountainburg 72946 14282 71-A-0871 Alexander, Marilyn & James B & M's Kennel 245 Mt. -

Marxman Mary Jane Girls Mary Mary Carolyne Mas

Key - $ = US Number One (1959-date), ✮ UK Million Seller, ➜ Still in Top 75 at this time. A line in red 12 Dec 98 Take Me There (Blackstreet & Mya featuring Mase & Blinky Blink) 7 9 indicates a Number 1, a line in blue indicate a Top 10 hit. 10 Jul 99 Get Ready 32 4 20 Nov 04 Welcome Back/Breathe Stretch Shake 29 2 MARXMAN Total Hits : 8 Total Weeks : 45 Anglo-Irish male rap/vocal/DJ group - Stephen Brown, Hollis Byrne, Oisin Lunny and DJ K One 06 Mar 93 All About Eve 28 4 MASH American male session vocal group - John Bahler, Tom Bahler, Ian Freebairn-Smith and Ron Hicklin 01 May 93 Ship Ahoy 64 1 10 May 80 Theme From M*A*S*H (Suicide Is Painless) 1 12 Total Hits : 2 Total Weeks : 5 Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 12 MARY JANE GIRLS American female vocal group, protégées of Rick James, made up of Cheryl Ann Bailey, Candice Ghant, MASH! Joanne McDuffie, Yvette Marine & Kimberley Wuletich although McDuffie was the only singer who Anglo-American male/female vocal group appeared on the records 21 May 94 U Don't Have To Say U Love Me 37 2 21 May 83 Candy Man 60 4 04 Feb 95 Let's Spend The Night Together 66 1 25 Jun 83 All Night Long 13 9 Total Hits : 2 Total Weeks : 3 08 Oct 83 Boys 74 1 18 Feb 95 All Night Long (Remix) 51 1 MASON Dutch male DJ/producer Iason Chronis, born 17/1/80 Total Hits : 4 Total Weeks : 15 27 Jan 07 Perfect (Exceeder) (Mason vs Princess Superstar) 3 16 MARY MARY Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 16 American female vocal duo - sisters Erica (born 29/4/72) & Trecina (born 1/5/74) Atkins-Campbell 10 Jun 00 Shackles (Praise You) -

2 to Be Somebody: Ambition and the Desire to Be Different

2 To Be Somebody: Ambition and the Desire to Be Different The context for difference This chapter aims to identify some of the bands that enjoyed chart success during the late 1970s and ’80s and identify their artistic traits by means of conversations with band members and those close to the bands. This chapter does not claim to be a definitive account or an inclusive list of innovative bands but merely a viewpoint from some of the individuals who were present at the time and involved in music, creativity and youth culture. Some of these individuals were in the eye of the storm while others were more on the periphery. However, common themes emerge and testify to the Scouse resilience identified in the previous chapter. Also, identifying objective truth is a difficult task, as one band member will often have a view of his band’s history that conflicts with that of other members of the same band. As such, it is acknowledged that this chapter presents only selective viewpoints. Trying something new: In what ways were the Liverpool bands creative and different? ‘Liverpool has always made me brave, choice-wise. It was never a city that criticized anyone for taking a chance.’ David Morrissey1 In terms of creativity, the theory underpinning this book which was stated in Chapter 1 is that successful Liverpool bands in the 1980s were different from each other and did not attempt to follow the latest local or national pop music trends. None of the bands interviewed falls into the categories of punk, disco or New Romantic, which were popular trends at the time. -

1 Remembering Athlii Gwaii Managing Our Own Affairs

October 2010 REMEMBERING MANAGING TO PASS ATHLII GWAII OUR OWN ON EVERY- page 6 AFFAIRS THING page 10 page 13 HAIDAHAIDANews of the Haida Nation LAASLAASOCTOBER 2010 Justine Parnell 1 Haida Laas - News of the Haida Nation October 2010 CHN Taan Forest Energy NEW HIRES AT WORK IN THE OFF THE GRID In Remembrance Amanda Reid-Stevens has taken on WOODS The National Research Council of Taan Forest is actively completing These are people from the Haida community who passed away the position of Business Manager & Canada is starting work with the since October, 2009: Special Projects Coordinator at cutblock layout and design on Haida CHN to research energy technolo- Haida Laas. Gwaii that is consistent with the in- gies, proven and emerging, with the Old Massett Skidegate tent of the draft Land Use Order. intent to provide a reliable power Viola (Edwards) Atkins David Charles Wesley Teresa Adams has been hired as supply and reduce greenhouse gas Priscilla Marks Ronald (Beans) Collinson Policy Analyst and will be working to Taan Forest tendered opportunities emissions for the Islands. This project Emily Goertzen Douglas (Dougie) Royal Crosby support the CHN policy committee. for contract bids through its web site is called the Clean Technology Proj- Larry Davis Willis Royal Crosby < taanforest.com > and has recently ect and will turn Haida Gwaii into a Willy Russ Nellie Cross Deena Manitobenis has taken over retained three engineering consult- Clean Technology Research site. James Edwards Eleanor Russ front-line/front-desk responsibilities ing firms to manage cutblock layout Sam Davis Sr. Wayne Young HAIDA LAAS at CHN Old Massett; Marvin Col- within Taan’s forest operating area. -

By Brian Welsh

BEATS BY BRIAN WELSH SYNOPSIS 1994, a small town in central Scotland. Best mates Johnno and Spanner share a deep bond. Now on the cusp of adulthood, life is destined to take them in different directions – Johnno’s family are moving him to a new town and a better life, leaving Spanner behind to face a precarious future. But this summer is going to be different for them, and for the country. The explosion of the free party scene and the largest counter-cultural youth movement in recent history is happening across the UK. In pursuit of adventure and escape, the boys head out on one last night together to an illegal rave. Stealing cash from Spanner’s older brother, under the hazy stewardship of pirate radio DJ D-Man, the boys journey into an underworld of anarchy, freedom and a full-on collision with the forces of law and order. A universal coming of age story, set to a soundtrack as eclectic and electrifying as the scene it gave birth to, BEATS is a story for our time – of friendship, rebellion and the irresistible power of gathered youth. DIRECTOR: Brian Welsh PRODUCER: Camilla Bray EXEC. PRODUCER: Steven Soderbergh SCREENPLAY: Kieran Hurley, Brian Welsh MUSIC: JD Twitch (Optimo) CAST: Cristian Ortega, Lorn Macdonald, Laura Fraser Q&A WITH BRIAN WELSH How did you come to be involved with BEATS, which is based on Kieran Hurley’s 2012 play of the same name? A friend said, “You have to see this show playing at the Bush Theatre in London – it’s about you growing up.” When I read the synopsis of BEATS – this story about a 15-year-old boy going to a rave at the time the Criminal Justice Act was introduced – I grabbed a ticket and went along. -

Drummer Persona Llista

Drummer Persona Llista Mavelikara Krishnankutty Nair https://ca.listvote.com/lists/person/mavelikara-krishnankutty-nair-15435509 Sampsa Astala https://ca.listvote.com/lists/person/sampsa-astala-927469 Colin Burgess https://ca.listvote.com/lists/person/colin-burgess-555933 Ari Toikka https://ca.listvote.com/lists/person/ari-toikka-11852523 Jon Dette https://ca.listvote.com/lists/person/jon-dette-1282431 Lacu https://ca.listvote.com/lists/person/lacu-5931968 Tue Madsen https://ca.listvote.com/lists/person/tue-madsen-2304274 Rudy Lenners https://ca.listvote.com/lists/person/rudy-lenners-612692 Lyly Rajala https://ca.listvote.com/lists/person/lyly-rajala-11879931 Jay Schellen https://ca.listvote.com/lists/person/jay-schellen-6167162 Juha Jokinen https://ca.listvote.com/lists/person/juha-jokinen-11867357 Mark Zonder https://ca.listvote.com/lists/person/mark-zonder-3849588 Seppo Alvari https://ca.listvote.com/lists/person/seppo-alvari-11892961 Kate Schellenbach https://ca.listvote.com/lists/person/kate-schellenbach-3813331 Daniele Trambusti https://ca.listvote.com/lists/person/daniele-trambusti-3702095 Keith Carlock https://ca.listvote.com/lists/person/keith-carlock-6384168 Pelle Lidell https://ca.listvote.com/lists/person/pelle-lidell-5950246 Mike Sturgis https://ca.listvote.com/lists/person/mike-sturgis-6848976 Blair Cunningham https://ca.listvote.com/lists/person/blair-cunningham-4924073 Tomi Parkkonen https://ca.listvote.com/lists/person/tomi-parkkonen-5492988 Stet Howland https://ca.listvote.com/lists/person/stet-howland-1094599 Chris Kontos -

Spi Spiritualized

Nummer 6 • 2001 | Sveriges största musiktidning Tool J Mascis Mercury Rev Fjärde världen Julee Cruise SpiritSpi ualized Kaah • The (International) Noise Conspiracy • The Haunted • Danko Jones • Henry Rollins Groove 6 • 2001 Ledare Chefredaktör & ansvarig utgivare Gary Andersson, [email protected] Bildredaktör Vad är det Johannes Giotas, [email protected] Skivredaktör Per Lundberg Gonzalez-Bravo, [email protected] som händer? Layout Henrik Strömberg, [email protected] Redigering Sommaren 2001 var fantastisk – men ändå Gary Andersson, Henrik Strömberg Danko Jones sid. 5 blev allt så fel. Vad jag syftar på är i första hand två händelser. Annonser Tre frågor till Henry Rollins sid. 5 De soldränkta festligheterna i Hultsfred Per Lundberg G.B. blev plötsligt mindre festliga när oroligheter- ”Hin håles favoritlyra” sid. 5 na i toppmötets Göteborg brakade lös via Distribution Division of Laura Lee sid. 6 TV. Katastrof är ordet. Även vad gäller rap- Karin Stenmar [email protected] porteringen i media. Frågan är om vi alls Web ”Varför är jag speciell?” sid. 6 kommer att få en någorlunda objektiv bild Ann-Sofie Henricson, Therese Söderling The Haunted sid. 7 av vem som gjorde sig skyldig till vad. Och hur startade kaoset egentligen? Var det verk- April Tears sid. 8 ligen professionella huliganer som letade bråk eller hetsade polisens osmidiga taktik Grooveredaktion Julee Cruise sid. 8 fram reaktioner från naiva ungdomar? Dan Andersson Per Lundberg G.B. Fjärde världen sid. 9 Konserterna nere i Småland tappade i alla fall sin spänning. Gary Andersson Björn Magnusson Irmin Schmidt & Kumo sid. 11 Och sen gick Aaliyah bort för nån vecka Johan Björkegren Thomas Nilson Niclas Ekström Thomas Olsson Tool sid. -

Sunraysia Daily Index 1982-1999

SUNRAYSIA DAILY INDEX 1982-1999 NAME DATE KEY AANENSEN Elsie May 1990 D.F AARTSEN Jack 1996 D.F ABBOTT Frederick George J. 1993 D.F ABBOTT George William 1992 D.F ABBOTT Jessie Maria 1995 D.F ABBOTT Jillian 1987 M A'BECKETT (MORRISON) Emily Elizabeth 1988 B A'BECKETT Noel 1989 M ABEL - SCHILLING Robert & Tracie 1994 M ABEL (SCHILLING) Chelsea Amanda 1998 B ABELL Ann 1986 D ABELL Ann 1986 F ABELL Jack 1991 D.F ABELL Jack 1991 OBIT ABELL Kim 1995 M ABERNETHY Phillip John 1993 D.F ABLETT - DOUGLAS Trevor & Karen 1992 M.A ABLETT - DOUGLAS Trevor & Keren 1992 M ABLETT (BATH) Todd James 1996 B ABLETT (DOUGLAS) Edward James 1993 B ABLETT (DOUGLAS) Hamish Douglas 1998 B ABLETT (NASH) Daniel Luke 1997 B ABLETT (NASH) James Lachlan 1992 B ABLETT (NASH) Thomas Samuel 1995 B ABLETT (TURLEY) Mathew John 1987 B ABLETT (TURLEY) Michael Ryan 1990 B ABLETT (WAGNER) Olive Jean 1997 D.F ABLETT Bill & Olive (Golden) 1982 M ABLETT Bill (Golden) 1982 M ABLETT Dick 1994 MEM ABLETT Geoffrey 1985 M ABLETT George William 1999 D.F ABLETT Henry J. R. 1995 MEM ABLETT Henry J. Richard 1992 F ABLETT Henry James R. 1992 D.F ABLETT J. H. R. (Dick) 1993 MEM ABLETT Renee Louise 1985 D ABLETT Renee Louise 1985 F ABLETT Sue 1983 M ABLETT William Edward 1984 D.F ABLETT William Edward 1985 MEM ABLETT William Edward 1985 MEM ABRAHAM - MUNRO Valerie & Barry 1993 M ABRAHAM Elizabeth 1989 D ABRAHAM Emmanuel & Mrs. (Gold) 1982 M ABRAHAM Mannie 1984 MEM ABRAHAM Mannie 1985 MEM ABRAHAM Mannie 1986 MEM ABRAHAM Mannie 1987 MEM ABRAHAM Mannie 1988 MEM ABRAHAM Manuel 1983 MEM ABRAMOVIC -

Une Bibliographie Commentée En Temps Réel : L'art De La Performance Au Québec Et Au Canada

Une bibliographie commentée en temps réel : l’art de la performance au Québec et au Canada An Annotated Bibliography in Real Time: Performance Art in Quebec and Canada (2017/2018) Une bibliographie commentée en temps réel : l’art de la performance au Québec et au Canada An Annotated Bibliography in Real Time: Performance Art in Quebec and Canada 2014 – 2020 Chercheure responsable : Professeure Dr phil Barbara Clausen, UQAM DéparteMent d’histoire de l’art Partenaires (s’il y a lieu) : Bibliothèque des arts UQAM et Artexte Montréal. Organisme subventionnaire : FRQSC (2016-2019) PARFAC (2014-2015) Équipe de recherche 2016 – 2019 Jade Boivin, EMManuelle Choquette, Geneviève Marcil, Maude Lefebvre, CaMille Richard (étudiantes de Maitrise en histoire de l’art) 2014 – 2015 Jade Boivin, EMManuelle Choquette, Joëlle Perron-Oddo, Julie Riendeau (étudiantes de Maitrise en histoire de l’art) Description Ce projet de recherche universitaire Une bibliographie coMMentée : l’art de la perforMance au Québec et au Canada, vise à dresser l’inventaire des textes et des ouvrages que des théoricien.ne.s, critiques, artistes, conservateur.trice.s et autres auteur.trice.s ont rédigés par anticipation, en réaction ou en réponse à l’art perforMatif. Le projet de recherche vise la réalisation d’un survol des histoires coMplexes et reMarquableMent Multidisciplinaires de la perforMance au Québec et au Canada. L’objectif est de procéder à une identification et à une évaluation globale des Modes de production reliés et corrélés qui sont au cœur de la théorie, de l’histoire et de la pratique de la perforMance au niveau local, provincial et national depuis le début du XXe siècle. -

Artist Album Type Label Num Tracks URI 200 the Breakdown Single Mental Madness Records 3 200 the Darkness Single Mental Madness

Num Artist Album Type Label tracks URI Mental Madness 200 The Breakdown single Records 3 http://open.spotify.com/album/1Cje7L9u6ps7JscQjLwf26 Mental Madness 200 The Darkness single Records 6 http://open.spotify.com/album/7zxaIBSDmaS7Aq4P02ESJn KONTOR 666 Atencion single RECORDS 5 http://open.spotify.com/album/2e3w31RJ3Mr4aqhqFfGzDg Mental Madness 666 Progressive D.E.V.I.L. single Records 2 http://open.spotify.com/album/1Xz0fUaZdOo8aG24sPMUES !wagero! Anata Ni Love Letter single BMG Japan 1 http://open.spotify.com/album/2QAuNGLWX2uOExdrz1FqDl *NSYNC Celebrity album Jive 13 http://open.spotify.com/album/7zBue2Vuzg4Z3ncRXaIkJg RCA Records *NSYNC Home For Christmas album Label 14 http://open.spotify.com/album/642MvjqEgywTy3nMsUe3Xk RCA Records *NSYNC Home For Christmas album Label 14 http://open.spotify.com/album/6uIB97CqMcssTss9WrtX8c *NSYNC Home For Christmas album Transcontinental 14 http://open.spotify.com/album/2jhsj4flihVGi0Wx44VRls Beton Kopf :wumpscut: Boeses Junges Fleisch album Media 13 http://open.spotify.com/album/3KBT4eI3esZYzWSKjlN904 Boeses Junges Fleisch - 7th Beton Kopf :wumpscut: Anniversary Edition album Media 15 http://open.spotify.com/album/0fl9xtq8566yMquWJap3Vn Beton Kopf :wumpscut: Bunkertor 7 album Media 12 http://open.spotify.com/album/58qNTStR1ihlvWHj5gg24a Beton Kopf :wumpscut: Cannibal Anthem album Media 11 http://open.spotify.com/album/4AYJ5ZCfCYRjxyNKxTgXKc Dried Blood Of Gomorrha Beton Kopf :wumpscut: Remastered album Media 10 http://open.spotify.com/album/241SguWSt4jFNf3mdyDpoY Dried Blood Of Gomorrha Beton