Provincial Geographies of India (Volume 2).Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ethiopia and India: Fusion and Confusion in British Orientalism

Les Cahiers d’Afrique de l’Est / The East African Review 51 | 2016 Global History, East Africa and The Classical Traditions Ethiopia and India: Fusion and Confusion in British Orientalism Phiroze Vasunia Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/eastafrica/314 Publisher IFRA - Institut Français de Recherche en Afrique Printed version Date of publication: 1 March 2016 Number of pages: 21-43 ISSN: 2071-7245 Electronic reference Phiroze Vasunia, « Ethiopia and India: Fusion and Confusion in British Orientalism », Les Cahiers d’Afrique de l’Est / The East African Review [Online], 51 | 2016, Online since 07 May 2019, connection on 08 May 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/eastafrica/314 Les Cahiers d’Afrique de l’Est / The East African Review Global History, East Africa and the Classical Traditions. Ethiopia and India: Fusion and Confusion in British Orientalism Phiroze Vasunia Can the Ethiopian change his skinne? or the leopard his spots? Jeremiah 13.23, in the King James Version (1611) May a man of Inde chaunge his skinne, and the cat of the mountayne her spottes? Jeremiah 13.23, in the Bishops’ Bible (1568) I once encountered in Sicily an interesting parallel to the ancient confusion between Indians and Ethiopians, between east and south. A colleague and I had spent some pleasant moments with the local custodian of an archaeological site. Finally the Sicilian’s curiosity prompted him to inquire of me “Are you Chinese?” Frank M. Snowden, Blacks in Antiquity (1970) The ancient confusion between Ethiopia and India persists into the late European Enlightenment. Instances of the confusion can be found in the writings of distinguished Orientalists such as William Jones and also of a number of other Europeans now less well known and less highly regarded. -

Multi- Hazard District Disaster Management Plan

MULTI –HAZARD DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN, BIRBHUM 2018-2019 MULTI – HAZARD DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN BIRBHUM - DISTRICT 2018 – 2019 Prepared By District Disaster Management Section Birbhum 1 MULTI –HAZARD DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN, BIRBHUM 2018-2019 2 MULTI –HAZARD DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN, BIRBHUM 2018-2019 INDEX INFORMATION 1 District Profile (As per Census data) 8 2 District Overview 9 3 Some Urgent/Importat Contact No. of the District 13 4 Important Name and Telephone Numbers of Disaster 14 Management Deptt. 5 List of Hon'ble M.L.A.s under District District 15 6 BDO's Important Contact No. 16 7 Contact Number of D.D.M.O./S.D.M.O./B.D.M.O. 17 8 Staff of District Magistrate & Collector (DMD Sec.) 18 9 List of the Helipads in District Birbhum 18 10 Air Dropping Sites of Birbhum District 18 11 Irrigation & Waterways Department 21 12 Food & Supply Department 29 13 Health & Family Welfare Department 34 14 Animal Resources Development Deptt. 42 15 P.H.E. Deptt. Birbhum Division 44 16 Electricity Department, Suri, Birbhum 46 17 Fire & Emergency Services, Suri, Birbhum 48 18 Police Department, Suri, Birbhum 49 19 Civil Defence Department, Birbhum 51 20 Divers requirement, Barrckpur (Asansol) 52 21 National Disaster Response Force, Haringahata, Nadia 52 22 Army Requirement, Barrackpur, 52 23 Department of Agriculture 53 24 Horticulture 55 25 Sericulture 56 26 Fisheries 57 27 P.W. Directorate (Roads) 1 59 28 P.W. Directorate (Roads) 2 61 3 MULTI –HAZARD DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN, BIRBHUM 2018-2019 29 Labpur -

Village & Town Directory ,Darjiling , Part XIII-A, Series-23, West Bengal

CENSUS OF INDIA 1981 SERmS 23 'WEST BENGAL DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PART XIll-A VILLAGE & TO"WN DIRECTORY DARJILING DISTRICT S.N. GHOSH o-f the Indian Administrative Service._ DIRECTOR OF CENSUS OPERATIONS WEST BENGAL · Price: (Inland) Rs. 15.00 Paise: (Foreign) £ 1.75 or 5 $ 40 Cents. PuBLISHED BY THB CONTROLLER. GOVERNMENT PRINTING, WEST BENGAL AND PRINTED BY MILl ART PRESS, 36. IMDAD ALI LANE, CALCUTTA-700 016 1988 CONTENTS Page Foreword V Preface vn Acknowledgement IX Important Statistics Xl Analytical Note 1-27 (i) Census ,Concepts: Rural and urban areas, Census House/Household, Scheduled Castes/Scheduled Tribes, Literates, Main Workers, Marginal Workers, N on-Workers (ii) Brief history of the District Census Handbook (iii) Scope of Village Directory and Town Directory (iv) Brief history of the District (v) Physical Aspects (vi) Major Characteristics (vii) Place of Religious, Historical or Archaeological importance in the villages and place of Tourist interest (viii) Brief analysis of the Village and Town Directory data. SECTION I-VILLAGE DIRECTORY 1. Sukhiapokri Police Station (a) Alphabetical list of villages 31 (b) Village Directory Statement 32 2. Pulbazar Police Station (a) Alphabetical list of villages 37 (b) Village Directory Statement 38 3. Darjiling Police Station (a) Alphabetical list of villages 43 (b) Village Directory Statement 44 4. Rangli Rangliot Police Station (a) Alphabetical list of villages 49- (b) Village Directory Statement 50. 5. Jore Bungalow Police Station (a) Alphabetical list of villages 57 (b), Village Directory Statement 58. 6. Kalimpong Poliee Station (a) Alphabetical list of viI1ages 62 (b)' Village Directory Statement 64 7. Garubatban Police Station (a) Alphabetical list of villages 77 (b) Village Directory Statement 78 [ IV ] Page 8. -

Baseline Study Report Integrated Flood Resilience Program

BASELINE STUDY REPORT INTEGRATED FLOOD RESILIENCE PROGRAM BASELINE STUDY REPORT INTEGRATED FLOOD RESILIENCE PROGRAM Study Team Biplob Kanti Mondal, Project Manager-Resilience & WASH, IFRC Md. Ashik Sarder, Disaster Management Offi cer, IFRC Md. Anisur Rahman, PMER Offi cer, BDRCS Review Team Md. Rafi qul Islam, Deputy Secretary General & Chief of DRM, BDRCS Md. Belal Hossain, Director, DRM Department, BDRCS Surendra Kumar Regmi, Program Coordinator, IFRC Md. Afsar Uddin Siddique, Deputy Director, DRM Department, BDRCS Maliha Ferdous, Senior Manager, Resilience & PRD, IFRC Overall Cooperation Mohammad Akbar Ali, Assistant Program Manager, DRM Department, BDRCS Md. Kamrul Islam, Senior Technical Offi cer, DRM Department, BDRCS Published by: Integrated Flood Resilience Program (IFRP) Disaster Risk Management (DRM) Department Bangladesh Red Crescent Society (BDRCS) 684-686, Red Crescent Sarak, Bara Moghbazar, Dhaka-1217, Bangladesh ISBN: 978-984-34-6445-3 Published in: April 2019 Printed by Graphnet Ltd. Cell: 01715011303 B Baseline Study Report Message from BDRCS Secretary General Bangladesh Red Crescent Society (BDRCS) Bangladesh Red Crescent Society is proud to closely work with IFRC and KOICA to bring the resilience capacity of the community people across Bangladesh. We are glad to implement the Integrated Flood Resilience Program (IFRP) that is technically supported by IFRC and funded by KOICA. The baseline study of IFRP has been conducted at four fl ood-prone communities of Nilphamari and Lalmonirhat and the study report has documented the scenario of the communities by identifying different issues of climate change, disaster risk, resilience, WASH, health, shelter and livelihood. The fi ndings of the baseline study report will be helpful to measure the progress of IFRP as well as to successfully implement the program. -

History of Indian Railways in Orissa (A Lot of It Borrowed from the SER Web Pages and Rest Compiled by Chitta Baral, [email protected])

History of Indian Railways in Orissa (a lot of it borrowed from the SER web pages and rest compiled by Chitta Baral, [email protected]) 1887 The Bengal Nagpur Railway was formed. 6th Oct 1890 The East Coast Railway was inaugurated. 1893 to 1896 800 miles of East Coast Railway line was built and opened for traffic. 1893 to 1896 East Coast Railway built some of the largest bridges viz. Brahmani, Mahanadi, Katjuri, Kuakhai and Birupa during the period. 1st Feb 1897 Khurda Road-Puri (27 miles) section was opened for traffic. 1898-99 Kharagpur-Cuttack was opened for traffic. 1st Jan 1899 BNR’s Line to Cuttack was opened. March 1901 The construction of a bridge on River Mahanadi near Cuttack was completed. 1911 A 40 mile branch line from Tatanagar to Gurumahisarani where plenty of iron ores are available was opened for traffic. 1922 BNR Hotel at Puri was established 1922 Tatanagar-Gurumahisani line was extended upto Badampahar. Feb 1925 Extension to Gua was completed. 1929-31 Parlakmedi-Gunupur section was opened in two portions in 1929 and 1931. 1st Oct 1944 The management of Bengal Nagpur Railway was taken by Government of India. 1955 B N R Emerged as South Eastern Railway. 1960 The Dandakaranya-Bolangir-Kiriburu Railway Project. [Kottavalasa- Koraput-Jeypore-Kirandul Construction (Dandakaranya Project), Titlagarh-Bolangir-Jharsuguda Project and Rourkela-Kiriburu Project; all these 3 projects put together were popularly known as DBK Project - Dandakaranya-Bolangir-Kiriburu Project.] 31st Jan 1962 Foundation stone of Cuttack-Paradip line was laid by the then Prime Minister, Late Jawarlal Nehru. -

Rivers of Peace: Restructuring India Bangladesh Relations

C-306 Montana, Lokhandwala Complex, Andheri West Mumbai 400053, India E-mail: [email protected] Project Leaders: Sundeep Waslekar, Ilmas Futehally Project Coordinator: Anumita Raj Research Team: Sahiba Trivedi, Aneesha Kumar, Diana Philip, Esha Singh Creative Head: Preeti Rathi Motwani All rights are reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without prior permission from the publisher. Copyright © Strategic Foresight Group 2013 ISBN 978-81-88262-19-9 Design and production by MadderRed Printed at Mail Order Solutions India Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai, India PREFACE At the superficial level, relations between India and Bangladesh seem to be sailing through troubled waters. The failure to sign the Teesta River Agreement is apparently the most visible example of the failure of reason in the relations between the two countries. What is apparent is often not real. Behind the cacophony of critics, the Governments of the two countries have been working diligently to establish sound foundation for constructive relationship between the two countries. There is a positive momentum. There are also difficulties, but they are surmountable. The reason why the Teesta River Agreement has not been signed is that seasonal variations reduce the flow of the river to less than 1 BCM per month during the lean season. This creates difficulties for the mainly agrarian and poor population of the northern districts of West Bengal province in India and the north-western districts of Bangladesh. There is temptation to argue for maximum allocation of the water flow to secure access to water in the lean season. -

Eastern India Pramila Nandi

P: ISSN NO.: 2321-290X RNI : UPBIL/2013/55327 VOL-5* ISSUE-6* February- 2018 E: ISSN NO.: 2349-980X Shrinkhla Ek Shodhparak Vaicharik Patrika Dimension of Water Released for Irrigation from Mayurakshi Irrigation Project (1985-2013), Eastern India Abstract Independent India has experienced emergence of many irrigation projects to control the river water with regulatory measures i.e. dam, barrage, embankment, canal etc. These irrigation projects were regarded as tools of development and it was thought that they will take the economy of the respective region to a higher level. Against this backdrop, the Mayurakshi Irrigation Project was initiated in 1948 with Mayurakshi as principal river and its four main tributaries namely Brahmani, Dwarka, Bakreswar and Kopai. This project aimed to supply water for irrigation to the agricultural field of the command area at the time of requirement and assured irrigation was the main agenda of this project’s commencement. In this paper the author has tried to find out the current status of the timely irrigation water supply which was the main purpose of initiation of this project. Keywords: Irrigation Projects, Regulatory Measures, Command Area, Assured Irrigation. Introduction In the post-independence period, India has shown accelerating trend in growth of irrigation projects. Following USA and other advanced economies of the time, independent India encouraged irrigation projects to ensure assured irrigation, flood control, generation of hydroelectricity. Then Prime Minister Jawhar Lal Neheru entitled the dams as temples of modern India. Mayurakshi Irrigation Project (MIP) was one of them and was Pramila Nandi launched in 1948 to serve water to the thirsty agricultural lands of one of Research Scholar, the driest district of West Bengal i.e. -

Mukhopadhyay, Aparajita (2013) Wheels of Change?: Impact of Railways on Colonial North Indian Society, 1855-1920. Phd Thesis. SO

Mukhopadhyay, Aparajita (2013) Wheels of change?: impact of railways on colonial north Indian society, 1855‐1920. PhD Thesis. SOAS, University of London http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/17363 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. Wheels of Change? Impact of railways on colonial north Indian society, 1855-1920. Aparajita Mukhopadhyay Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD in History 2013 Department of History School of Oriental and African Studies University of London 1 | P a g e Declaration for Ph.D. Thesis I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for students of the School of Oriental and African Studies concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part by any other person. I also undertake that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged in the work that I present for examination. -

Professor Horace Hayman Wilson, Ma, Frs

PEOPLE OF A WEEK AND WALDEN: PROFESSOR HORACE HAYMAN WILSON, MA, FRS “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project People of A Week and Walden HDT WHAT? INDEX PEOPLE OF A WEEK AND WALDEN: HORACE HAYMAN WILSON A WEEK: A Hindoo sage said, “As a dancer, having exhibited herself PEOPLE OF to the spectator, desists from the dance, so does Nature desist, A WEEK having manifested herself to soul —. Nothing, in my opinion, is more gentle than Nature; once aware of having been seen, she does not again expose herself to the gaze of soul.” HORACE HAYMAN WILSON HENRY THOMAS COLEBROOK WALDEN: Children, who play life, discern its true law and PEOPLE OF relations more clearly than men, who fail to live it worthily, WALDEN but who think that they are wiser by experience, that is, by failure. I have read in a Hindoo book, that “there was a king’s son, who, being expelled in infancy from his native city, was brought up by a forester, and, growing up to maturity in that state imagined himself to belong to the barbarous race with which he lived. One of his father’s ministers having discovered him, revealed to him what he was, and the misconception of his character was removed, and he knew himself to be a prince. So soul,” continues the Hindoo philosopher, “from the circumstances in which it is placed, mistakes its own character, until the truth is revealed to it by some holy teacher, and then it knows itself to be Brahme.” I perceive that we inhabitants of New England live this mean life that we do because our vision does not penetrate the surface of things. -

GIPE-017791-Contents.Pdf (2.126Mb)

OFFICIAL AG~NTS . FOR THE SALE OF GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS. In India. MESSRS. THA.CXBK, SPINK & Co., Calcutta and Simla. · MESSRS. NEWKA.N & Co., Calcutta. MESSRS. HIGGINBOTHA.M & Co., Madras. MESSRS. THA.Ci:BB & Co., Ln., Bombay. MESSRS . .A.. J. CoHBRIDGB & Co., Bombay. THE SUPERINTENDENT, .A.M:ERICA.N BA.l'TIS'l MISSION PRESS, Ran~toon. Mas. R.l.DHA.BA.I ATKARA.M SA.aooN, Bombay. llissas. R. CA.HBRA.Y & Co., Calcutta. Ru SA.HIB M. GuL&B SINGH & SoNs, Proprietors of the Mufid.i-am Press, Lahore, Punjab. MEsSRS. THoMPSON & Co., Madras. MESSRS. S. MuRTHY & Co., Madras. MESSRS. GoPA.L NA.RA.YEN & Co., Bombay. AhssRs. B. BuiERlEB & Co., 25 Cornwallis Street,· Calcutta. MBssas. S. K. LA.HlRI & Co., Printers and Booksellers, College Street, Calcutta. MESSRS. V. KA.LYA.NA.RUIA. IYER & Co., Booksellers, &c., Madras. MESSRS. D. B. TA.RA.POREVA.LA., SoNs & Co., Booksellers, Bombay. MESSRS. G. A; NA.TESON & Co., Madras. MR. N. B. MA.THUR, Superintendent, Nazair Kanum Hind Press, AJlahabad. - TnB CA.LCUTTA. ScHOOL Boox SociETY. MR. SUNDER PA.NDURA.NG, Bombay. MESSRs. A.M. A.ND J. FERGusoN, Ceylon. MEssRsrTEMPI.B & Co., Madras. · MEssRs. CoHBRIDGB & Co., Madras •. MESSRS. A. R. PILLA.I & Co., Trivandrum. ~bssRs. A. CHA.ND &-Co., Lahore, Punjab. ·- .·· BA.Bu S. C. T.A.LUXDA.B, Proprietor, Students & Co., Ooocli Behar. ------' In $ng~a»a.~ AIR. E. A. • .ARNOLD, 41 & 43 -M.ddo:x:• Street, Bond Street, London, W. , .. MESSRS. CoNSTA.BLB & Co., 10 Orange· Sheet, Leicester Square, London, W. C. , MEssRs. GaiNDLA.Y & Co., 64. Parliament Street, London, S. -

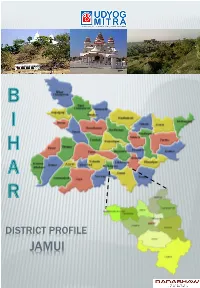

District Profile Jamui Introduction

DISTRICT PROFILE JAMUI INTRODUCTION Jamui district is one of the thirty-eight administrative districts of Bihar. The district was formed on 21 February 1991, when it was separated from Munger district. Jamui district is a part of Munger Commissionery. Jamui district is surrounded by the districts of Munger, Nawada, Banka and Lakhisarai and districts Giridih and Deoghar of Jharkhand state. The major rivers flowing in the district are Kiul, Burnar, Sukhnar, Nagi, Nakti, Ulai, Anjan, Ajay and Bunbuni HISTORICAL BACKGROUND Jamui has a glorious history. Historical existence of Jamui has been observed during the Mahabharta period. Jamui was earlier known as Jambhiyaagram. The old name of Jamui has been traced as Jambhubani in a copper plate kept in Patna Musuem. According to Jainism, the 24th Tirthankar Lord Mahavir got divine knowledge in Jambhiyagram/ Jrimbhikgram situated on the bank of river Jambhiyagram Ujjhuvaliya/ Rijuvalika. Hindi translation of the words Jambhiya and Jrimbhikgram is Jamuhi which developed in the recent time as Jamui and the river Ujhuvaliya/ Rijuvalika changed to river Ulai . Jamui was ruled by the Gupta, Pala and Chandel rulers. Indpai is supposed to be the capital of Indradyumna, the last local king of Pala dynasty during the 12th century. It was earlier known as Indraprastha. Many archaeological evidences have been found at this place. Gidhaur, also known as Patsanda, is a small town in Jamui district. It was one of the 568 Princely States in India before the partition of British India in 1947. Kings of Chandel descent belonging to Mahoba of Bundelkhand region, ruled here for more than six centuries. -

UNIT 2 INDIAN LANGUAGES Notes STRUCTURE 2.0 Introduction

Indian Languages UNIT 2 INDIAN LANGUAGES Notes STRUCTURE 2.0 Introduction 2.1 Learning Objectives 2.2 Linguistic Diversity in India 2.2.1 A picture of India’s linguistic diversity 2.2.2 Language Families of India and India as a Linguistic Area 2.3 What does the Indian Constitution say about Languages? 2.4 Categories of Languages in India 2.4.1 Scheduled Languages 2.4.2 Regional Languages and Mother Tongues 2.4.3 Classical Languages 2.4.4 Is there a Difference between Language and Dialect? 2.5 Status of Hindi in India 2.6 Status of English in India 2.7 The Language Education Policy in India Provisions of Various Committees and Commissions Three Language Formula National Curriculum Framework-2005 2.8 Let Us Sum Up 2.9 Suggested Readings and References 2.10 Unit-End Exercises 2.0 INTRODUCTION You must have heard this song: agrezi mein kehte hein- I love you gujrati mein bole- tane prem karu chhuun 18 Diploma in Elementary Education (D.El.Ed) Indian Languages bangali mein kehte he- amii tumaake bhaalo baastiu aur punjabi me kehte he- tere bin mar jaavaan, me tenuu pyar karna, tere jaiyo naiyo Notes labnaa Songs of this kind is only one manifestation of the diversity and fluidity of languages in India. We are sure you can think of many more instances where you notice a multiplicity of languages being used at the same place at the same time. Imagine a wedding in Delhi in a Telugu family where Hindi, Urdu, Dakkhini, Telugu, English and Sanskrit may all be used in the same event.