Strategy Ukraine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Criminal Charges Against Tymoshenko

ISSUE #01(120) IN THE SPOTLIGHT 01/21/2013 © Gorshenin institute January 2013 All rights reserved ISSUE #01(120) IN THE SPOTLIGHT 01/21/2013 Content 1. Criminal charges against Tymoshenko Tymoshenko faces charges of organizing murder; life sentence possible…page 4. Tymoshenko's trial adjourned; ex-premier protests against video surveillance…page 4. Tymoshenko complains about poisoning attempt…page 4. Ukrainian court to hear ex-premier's company's debt appeal on 21 January…page 4. 2. International political Ukraine-USA USA hopes for Tymoshenko's release by 2015…page 5. Ukraine-Russia Ukrainian president pushes for enhanced ties with Russia-led regional bloc…page 5. Ukraine, Russia seeking new formats of gas cooperation…page 5. Ukrainian president has no plans of visiting Moscow despite reports, press service says…page 5. Ukraine bought 33bn cu.m. of Russian gas in 2012…page 6. Ukraine-EU Ukraine's EU envoy: EU interested in setting up tripartite gas consortium…page 6. Ukraine-EU summit not to help visa-free travel…page 6. Ukraine-OSCE Ukraine chairs OSCE…page 6. 3. Domestic political Authorities Ukrainian president proposes to simplify rules for adopting orphans by foreigners…page 7. Ukrainian president appoints new security chief…page 7. Ukrainian parliament votes in favour of new top banker nominated by president…page 7. Ukrainian president might appoint new head of state-run energy firm…page 8. Ukrainian president appoints new head of state geology service…page 8. Ukrainian president restructures his administration…page 8. Ukrainian peacekeepers to be dispatched to Cote d'Ivoire…page 8. 2 © Gorshenin institute January 2013 All rights reserved ISSUE #01(120) IN THE SPOTLIGHT 01/21/2013 Ukrainian army might start employing only contract servicemen in 2013…page 8. -

In the Spotlight 11/11/2013

ISSUE 37 (156) IN THE SPOTLIGHT 11/11/2013 © Gorshenin Institute November 2013 All rights reserved ISSUE 37 (156) IN THE SPOTLIGHT 11/11/2013 CONTENT 1. Top news…page 4 2. International political…page 4 Ukraine-EU…page 4 European politicians do not rule out signing of association deal with Ukraine might be delayed Ukraine should fulfill EU requirements by 13 November – EU Parliament mission Ukrainian pro-presidential party questions benefits of country's European integration Ukrainian Foreign Ministry says draft declaration for Vilnius summit ready Ukraine may finish first stage of plan for simplifying visa regime with EU by Vilnius summit Ukraine-Russia…page 7 Ukraine starts paying off debt to Gazprom Ukraine might reconsider terms of contract with Russia on gas transit to Europe Russia to consider possibility of Ukraine's signing some Customs Union agreements Ukraine-IMF…page 8 IMF delays decision on Ukraine until December EU taking no part in Ukraine-IMF talks – media 3. Domestic political…page 9 Ukrainian authorities…page 9 Two bills required for EU bid pass first reading in parliament President endorses law which might prevent Klitschko from running for post President reshuffles governors in Odessa, Ivano-Frankivsk regions Ukrainians of call-up age now free to go abroad Ukrainian opposition…page 10 Ukrainian authorities begin new legal process against Tymoshenko Parliament sets up ad hoc group to work out law on Tymoshenko's treatment "Public debates" on Tymoshenko's treatment initiated in regions – media 2 © Gorshenin Institute November 2013 All rights reserved ISSUE 37 (156) IN THE SPOTLIGHT 11/11/2013 Opposition demands Yanukovych report on negotiations with Putin Court to consider Tymoshenko's UESU case on 6 December 4. -

Brussels Brussels Brussels Brussels Brussels Kiev Kiev

Interlocutors Meeting date Place Meeting Mr Andrii Goncharuk, Adviser of the President of Ukraine 09/01/2013 Brussels Meeting with Kostiantyn Yelisieiev, Head of the Mission of Ukraine to 17/01/2013 Brussels the EU Meeting with Mr Nemyria, Chairman of the Committee on European 28/01/2013 Brussels integration, Ukraine's Parliament Dinner with Mr Leonid Kozhara, Minister of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine 30/01/2013 Brussels Meeting Group of friends of Ukraine in the margins of FA Council, 31/01/2013 Brussels Ukrainian MFA Leonid Kozhara Official visit to Ukraine – Meetings with Mykola AZAROV, Prime 07/02/2013 Kiev Minister of Ukraine; Attend the meeting of the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine and speech; meets the heads of all parliamentary groups of the Verkhovna Rada; meeting with Valeriya LUTKOVSKA, Ukrainian Parliament's Commissioner for Human Rights Meeting with Viktor YANUKOVICH, President of Ukraine 08/02/2013 Kiev Lunch with Ukrainian MP Poroshenko 07/03/2013 Brussels Meeting with MP Arsenyi Yatsenyuk, Leader of the United Opposition 23/04/2013 Brussels in Ukraine and Chairman of ''Batkivshyna'' group in Ukrainian Parliament Meeting with Andriy Klyuyev, Secretary of Ukraine’s National Security 24/04/2013 Brussels and Defence Council Dinner with Sergiy Arbuzov, First Vice Prime Minister of Ukraine 29/04/2013 Brussels Meeting with Leonid Kozhara, Minister of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine, in 17/05/2013 Krakow margins of the meeting of the Ministers of Foreign Affairs of the Visegrad Group Meeting with Andriy Klyuyev, Secretary of Ukraine’s -

Anders Åslund

Anders Åslund Ukraine: What Went Wrong and How to Fix It Anders Åslund BESET BY RUSSIAN MILITARY AGGRESSION and the legacy from its years of economic mismanagement, Ukraine faces an existential crisis that has also roiled the politics of Europe. Yet there is a glimmer of hope and opportunity for this tormented country. In 2014 Ukraine carried out free and fair elections of a new president and parliament. With this democratic foundation, Ukraine can shape its future and return to economic and political stability. In this book, one of the world’s leading experts on Ukraine offers its new leadership a strategy for reform. Anders Åslund maintains that the country’s fundamental problem is corruption and poor governance, which requires radical reform of the state from the top down. He calls for the cleansing of the judiciary and law enforcement, including the abolition of the many intrusive inspection agencies, which use a regime of licenses, permits, and certifications to squeeze the lifeblood of the economy. The book also advocates cuts in wasteful public expenditures and deregulation to promote growth—but it also calls for international financing spearheaded by the International Monetary Fund. The European UKRAINE Union and the United States must also help. The book focuses extensively on the energy sector, which Åslund argues is the biggest source of top-level corruption and wasteful subsidies and should be reformed with a unified system of energy prices determined by the market, not government. Åslund also details a series of reforms in education and health care. To assure Ukraine’s success, the European Union must assume the role of anchor of the country’s democratic and market economic reforms. -

ANNUAL REPORT Message from the Chairman of the Chamber Board of Directors

2012 ANNUAL REPORT Message from the Chairman of the Chamber Board of Directors Dear Chamber Members, tees’ performance and internal and external communication. The same can be said about the successful development of the has put in Ukraine’s path, the Chamber and its executive team remainDespite focused all the on politicalthe future and and financial look forward challenges to the continuedthat 2012 - successes of the Chamber and each of its Members. Over the Business Networking platform – the Chamber has focused on- tomerfurther service. developing a well-rounded offering of benefits and ser vices by being proactive, innovative, and oriented towards cus last 20 years the Chamber has been striving to unite the leading- businesses in Ukraine, irrespective of their national origin, to On behalf of the Board of Directors I would like to once again work together to create a better business environment and fa express our sincere gratitude for the support and involvement cilitate new investment in the country’s economy. Celebration of of every one of our Member Companies. Their efforts have been the organization’s 20th Anniversary – a major milestone in the key to driving the Chamber’s activities in 2012. The road has areChamber’s proud to history have been – made a witness us once to again and participant think about in how Ukraine’s much proudnot always of. been easy, but by working together and supporting developmentthe country has as anaccomplished independent throughout nation as it all has these moved years. to emWe- each other we have collectively achieved a lot that we can be brace the principles that are the hallmarks of successful market Sincerely, economies. -

UKL) #462 Compiled by Dominique Arel Chair of Ukrainian Studies, U of Ottawa 8 December 2013

The Ukraine List (UKL) #462 compiled by Dominique Arel Chair of Ukrainian Studies, U of Ottawa www.ukrainianstudies.uottawa.ca 8 December 2013 1-Ukrainska pravda: Who Is Responsible for the Violence [UKL translation] 2-Human Rights in Ukraine: Halya Conash, On the Bankova Prisoners 3-Open Democracy: Anton Shekhovtsov, Provoking the Euromaidan 4-Facebook: Adrian Karatnycky on Korchynsky [with UKL translation] 5-Interfax-Ukraine: Three Former Ukrainian Presidents Support Maidan 6-Kyiv Post: Yanukovych’s Secret Meeting with Putin 7-New York Times: Oligarchs Are Split on Ukraine’s Path 8-Anthropology News: Anna Fournier, EU Protests and Gender Symbolism 9-Le Figaro (Paris): Interview with Dominique Arel [UKL translation] 10-Andreas Umland: On Svoboda and the EU 11-Le Fil (Laval): Interview with G. Daniel Caron [UKL translation] 12-NYRblog: Tim Snyder, A Way Out for Ukraine? 13-International NYT: Chrystia Freeland, In Kiev, High Stakes for Democracy 14-WSJ Europe: Karatnycky and Wilson, How to Defuse Ukraine’s Crisis 15-Kommersant (Russia): Aleksei Kudrin, Rules of the Game [JRL] 16-Bloomberg.com: Ukraine Spared the EU and Itself 17-National Interest: Ukraine Rejects Europe—A Blessing in Disguise? 18-Global Times (China): Ivaylo Gatev, Vilnius Fiasco Mirrors EU's Fading Halo 19-UCIPR: Stephen Velychenko, Ukraine the EU and the EU Left 20-The Monkey Cage: How Ukrainian Protestors are Using Twitter and Facebook 21-Forbes.com: Ukraine’s Demographically Emerging European Majority 22-New Book: Dragneva and Wolczuk, Eurasian Economic Integration 23-New Book: Maciej Olchawa, The European Integration of Ukraine 24-IISS: Charap and Troitskiy, Russian, the West and the Integration Dilemma 25/26-Mychailo Wynnyckyj’s EuroMaidan Diary: December 6, December 3 **Thanks to Nikolay Bilaniuk, G. -

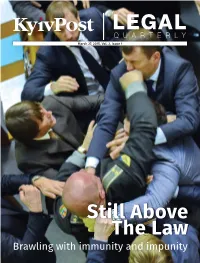

Still Above the Law Brawling with Immunity and Impunity

March 27, 2015, Vol. 2, Issue 1 Still Above The Law Brawling with immunity and impunity Editors’ Note Contents 4 Naftogaz vs. Gazprom: Battle of The Kyiv Post’s Legal Quarterly is now in its second year and still evolving based on your sug- giants gestions. So please keep new and better ideas coming our way! We launched this supplement to give readers a legal snapshot of the great political and 6 Many war-displaced Ukrainians business issues of the day. Ukraine’s legal and regulatory environment is changing rapidly in legal limbo and we see our role as keeping readers up to speed with the debates taking place. This is not meant to be an “insiders’ digest” written by and for lawyers. Rather, the Kyiv Post 8 Leonid Antonenko on how NBU will make banks accountable has found that Ukraine’s dynamic and competitive legal community is often the best – and sometimes the only – place to go for expert advice and commentary. Besides staying on top 10 Alternative energy market stung of all sides of the issues, many in Ukraine’s legal community also excel at breaking down with unfavorable rates the importance of complicated issues in easily understandable ways to the public (includ- ing journalists!). 11 No celebration yet, despite new We want to call your attention to a few of the best stories in this edition. law on business deregulation Everyone loves rankings and top lists. So do we. That’s why we asked Yurydychna Gazeta to share their latest survey of the top 100 lawyers in Ukraine. -

For Free Distribution

POLITICAL DEUCES PLAY INTO PAGE DISPELLING PAGE TOP 12 MUSIC PAGE THE HANDS OF THE GOVERNMENT FOOTBALL FANS' FESTIVALS BEFORE THE ELECTION 6 FEAR OF UKRAINE 36 THIS SUMMER 48 № 9 (32) JUNE 2012 NO LANGUAge – NO UKRAINE WWW.UKRAINIANWEEK.COM FOR FREE DISTRIBUTION Featuring selected content from The Economist Opposition vote |CONTENTS BRIEFING FOCUS ealers 9.8- Russification Redux? Total Political(eimates b yDeuces: A Royal Gift for the Language policy of the TPseudo-oppositionhe Ukrainian Government: A slew of facts party in power puts the projectsWeek) are stealing11.5 signal that the Presidential Ukrainian language the opposition’s Administration is promoting as well as Ukraine’s votes and play Natalia Korolevska’s political sovereignty and European foul in electoral project to help it take control choice at risk 4 commissions 6 of the future parliament 8 POLITICS Why Invest in European Stories: Matej Šurc and Blaž Culture? How Leonidas Donskis Zgaga investigate 5.4 2.9 – 0.4 0.3▪ 0.5- Ukrainian – on the role of0.7 the role of Slovenian officials4.1 are 3.1 1.6 literature and and Ukrainian top distorting storytelling in officials in arms Ukrainian politics trade with the cultureNatalia Hr10omadianska Nasha Oleh Ukrainian Others 12 Balkans 13 Korolevska's pozytsia Ukrayina Liashko's People's (eimates NEIGHBOURS SECURITY Ukrayina - (Civil (Our Radical Party by The The Difficult Vpered! Position) UkrEdwardaine) ChowPart ony how Ukrainian Bernard Path towards (Ukraine - Forwrwaarrdd!)!) Ukrainian authorities Week) Kouchner: Security Reform can decrease If you want to live in Ukraine dependence on Russian in a better world, Support from voters gas, yet put themselves it's all possible intending to vote in the eleion, % 16 in an ever worse 18 in the EU 20 Based position instead 0,0 on Razumkov ECONOMICS Centre poll held INVESTIGATION on 14-19 April 23.3 2012 The Illusion of Reforms26.7 According to Armed and 7.7 10.1 5.7 Based Macroeconomic28.2 Schumpeter: Unpunished: The 0,0 28.6 5.1 on KMIS Stability: why 8.5 The book confirms that10. -

Ukraine After the Parliamentary Elections Review and Outlook

1/2|2013 KAS INTERNATIONAL REPORTS 109 UKRAINE AFTER THE PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS REVIEW AND OUTLOOK Gabriele Baumann / Christine Rosenberger The parliamentary elections held in Ukraine on 28 October 2012 were heralded in advance by the European Union as an important event on the path to democratic development in the country. It was regarded that the course of the elec- toral campaign as well as the electoral process itself would have a direct influence on the questions of whether and when the already negotiated association agreement can be signed. A review shows that the elections did not meet Gabriele Baumann is European standards. This is clearly reflected in the opinions Resident Represent- ative of the Konrad- of national and international electoral observers, the oppo- Adenauer-Stiftung in sition parties as well as the High Representative of the EU the Ukraine. and the European Commission. Signing of the agreement has now been made conditional on having the mistakes corrected and promulgating an electoral law which meets European standards, rather than having the law modified prior to each election in accordance with the requirements of the ruling party. In spite of the massive manipulation and targeted use of Christine Rosenberger administrative resources well in advance of the election is a trainee at the day, the parliamentary elections produced a strong oppo- Konrad-Adenauer- sition. It had not been expected that such a clear result Stiftung in Kiev. would be delivered. The former governing party, the Party of Regions (PR) led by President Viktor Yanukovych, did emerge as the strongest force, but was weakened. -

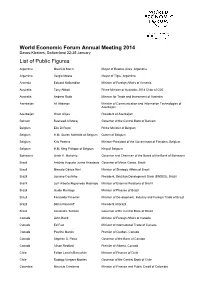

List of Public Figures

World Economic Forum Annual Meeting 2014 Davos-Klosters, Switzerland 22-25 January List of Public Figures Argentina Mauricio Macri Mayor of Buenos Aires, Argentina Argentina Sergio Massa Mayor of Tigre, Argentina Armenia Edward Nalbandian Minister of Foreign Affairs of Armenia Australia Tony Abbott Prime Minister of Australia; 2014 Chair of G20 Australia Andrew Robb Minister for Trade and Investment of Australia Azerbaijan Ali Abbasov Minister of Communication and Information Technologies of Azerbaijan Azerbaijan Ilham Aliyev President of Azerbaijan Bahrain Rasheed Al Maraj Governor of the Central Bank of Bahrain Belgium Elio Di Rupo Prime Minister of Belgium Belgium H.M. Queen Mathilde of Belgium Queen of Belgium Belgium Kris Peeters Minister-President of the Government of Flanders, Belgium Belgium H.M. King Philippe of Belgium King of Belgium Botswana Linah K. Mohohlo Governor and Chairman of the Board of the Bank of Botswana Brazil Antônio Augusto Junho Anastasia Governor of Minas Gerais, Brazil Brazil Marcelo Côrtes Neri Minister of Strategic Affairs of Brazil Brazil Luciano Coutinho President, Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES), Brazil Brazil Luiz Alberto Figueiredo Machado Minister of External Relations of Brazil Brazil Guido Mantega Minister of Finance of Brazil Brazil Fernando Pimentel Minister of Development, Industry and Foreign Trade of Brazil Brazil Dilma Rousseff President of Brazil Brazil Alexandre Tombini Governor of the Central Bank of Brazil Canada John Baird Minister of Foreign Affairs of Canada Canada Ed Fast Minister -

How to Get Rid of Post-Sovietness?

HOW TO GET RID OF POST-SOVIETNESS? Кyiv 2012 The project was implemented by the Institute of World Policy with the sup- port of the Black Sea Trust for Regional Cooperation. Opinions expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent those of the Black Sea Trust of the Ger- man Marshall Fund. Study prepared by expert groups: UKRAINE: Alyona Getmanchuk Zhanna Bezp’yatchuk Volodymyr Kravchenko Oksana Pyliavets Sergiy Solodkyy REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVA: Leonid Litra Cornel Ciurea Eduard Tugui GEORGIA: Teimuraz Kancheli The Institute of World Policy expresses its sincere gratitude for the support in the realization of the project to Dr. Martin Brusis (Ludwig Maximilian University of Mu- nich), Mr. Volodymyr Fesenko (Center for Applied Political Studies ‘Penta’), Yevhen Golovakha (National Academy of Scinces of Ukraine, Institute of Sociology). © Institute of World Policy, 2012 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION …………………………………………………… 4 Politics ……………………………………………………… 6 Society ……………………………………………………… 9 UKRAINE Post-Sovietness in Ukrainian Politics ………………… 12 Post-Sovietness in Ukrainian Society ………………… 41 REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVA Post-Sovietness in Moldovan Politics ………………… 70 Post-Sovietness in Moldovan Society ………………… 87 GEORGIA Post-Sovietness in Georgian Politics ………………… 103 Post-Sovietness in Georgian Society ………………… 121 10 RECOMMENDATIONS TO GET RID OF POST-SOVIETNESS ………………………… 137 3 HOW TO GET RID OF POST-SOVIETNESS? INTRODUCTION How does the post-Sovietness man- mental changes and correction of be- ifest itself in politics and public life, haviour patterns. and how to minimize its most harm- This study was inspired by the ful displays for the development of a transformational changes that have European state — these are two key taken place in recent years in the questions that the IWP tried to an- three countries of the region. -

Martin Ukraine 1

Martin Ukraine 1 Martin Ukraine Table of Contents International Marketing Project Introduction …………………………………………………………………………………….. 3 Issue ……………………………………………………………………………………………... 3 Non-Profit ………………………………………………………………………………………. 5 Geographical Area Analysis ………………………………………………………………… 6 Economic Analysis: Part 1 …………………………………………………………………….. 8 Economic Analysis: Part 2 …………………………………………………………………… 12 Political System ……………………………………………………………………………… 15 Trade Laws and Legal Analysis …………………………………………………………… 18 Population …………………………………………………………………………………… 20 Diet and Nutrition …………………………………………………………………………… 23 Housing ……………………………………………………………………………………… 26 Transportation ……………………………………………………………………………… 28 Labor …………………………………………………………………………………………. 30 Education …………………………………………………………………………………… 31 Clothing ……………………………………………………………………………………… 33 Recreation and Leisure …………………………………………………………………… 34 Language …………………………………………………………………………………… 36 Religion …………………………………………………………………………………….. 41 Bibliography ………………………………………………………………………………… 43 Appendix ……………………………………………………………………………………… 56 2 Martin Ukraine Introduction International Marketing Project The country, Ukraine has been chosen by BIS Inc. to be the host of the non-profit organization “Healing Acts of Ukraine”. Research has been done on numerous topics including the geography, economy, political system, labor, education, clothing, language, etiquette, and housing of Ukraine. All of these subjects are detailed in depth later in this project. All the research has been done on Ukraine to gain a very good understanding