6.21.19 V8 Formatted P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

L'opéra Moby Dick De Jake Heggie

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 20 | 2020 Staging American Nights L’opéra Moby Dick de Jake Heggie : de nouveaux enjeux de représentation pour l’œuvre d’Herman Melville Nathalie Massoulier Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/26739 DOI : 10.4000/miranda.26739 ISSN : 2108-6559 Éditeur Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Référence électronique Nathalie Massoulier, « L’opéra Moby Dick de Jake Heggie : de nouveaux enjeux de représentation pour l’œuvre d’Herman Melville », Miranda [En ligne], 20 | 2020, mis en ligne le 20 avril 2020, consulté le 16 février 2021. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/26739 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/ miranda.26739 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 16 février 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. L’opéra Moby Dick de Jake Heggie : de nouveaux enjeux de représentation pour ... 1 L’opéra Moby Dick de Jake Heggie : de nouveaux enjeux de représentation pour l’œuvre d’Herman Melville Nathalie Massoulier Le moment où une situation mythologique réapparaît est toujours caractérisé par une intensité émotionnelle spéciale : tout se passe comme si quelque chose résonnait en nous qui n’avait jamais résonné auparavant ou comme si certaines forces demeurées jusque-là insoupçonnées se mettaient à se déchaîner […], en de tels moments, nous n’agissons plus en tant qu’individus mais en tant que race, c’est la voix de l’humanité tout entière qui se fait entendre en nous, […] une voix plus puissante que la nôtre propre est invoquée. -

Bob Dylan: the 30 Th Anniversary Concert Celebration” Returning to PBS on THIRTEEN’S Great Performances in March

Press Contact: Harry Forbes, WNET 212-560-8027 or [email protected] Press materials; http://pressroom.pbs.org/ or http://www.thirteen.org/13pressroom/ Website: http://www.pbs.org/wnet/gperf/ Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/GreatPerformances Twitter: @GPerfPBS “Bob Dylan: The 30 th Anniversary Concert Celebration” Returning to PBS on THIRTEEN’s Great Performances in March A veritable Who’s Who of the music scene includes Eric Clapton, Stevie Wonder, Neil Young, Kris Kristofferson, Tom Petty, Tracy Chapman, George Harrison and others Great Performances presents a special encore of highlights from 1992’s star-studded concert tribute to the American pop music icon at New York City’s Madison Square Garden in Bob Dylan: The 30 th Anniversary Concert Celebration in March on PBS (check local listings). (In New York, THIRTEEN will air the concert on Friday, March 7 at 9 p.m.) Selling out 18,200 seats in a frantic, record-breaking 70 minutes, the concert gathered an amazing Who’s Who of performers to celebrate the 30th anniversary of the enigmatic singer- songwriter’s groundbreaking debut album from 1962, Bob Dylan . Taking viewers from front row center to back stage, the special captures all the excitement of this historic, once-in-a-lifetime concert as many of the greatest names in popular music—including The Band , Mary Chapin Carpenter , Roseanne Cash , Eric Clapton , Shawn Colvin , George Harrison , Richie Havens , Roger McGuinn , John Mellencamp , Tom Petty , Stevie Wonder , Eddie Vedder , Ron Wood , Neil Young , and more—pay homage to Dylan and the songs that made him a legend. -

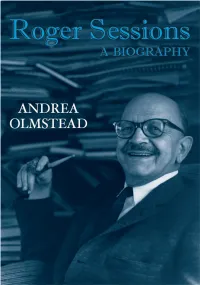

Roger Sessions: a Biography

ROGER SESSIONS: A BIOGRAPHY Recognized as the primary American symphonist of the twentieth century, Roger Sessions (1896–1985) is one of the leading representatives of high modernism. His stature among American composers rivals Charles Ives, Aaron Copland, and Elliott Carter. Influenced by both Stravinsky and Schoenberg, Sessions developed a unique style marked by rich orchestration, long melodic phrases, and dense polyphony. In addition, Sessions was among the most influential teachers of composition in the United States, teaching at Princeton, the University of California at Berkeley, and The Juilliard School. His students included John Harbison, David Diamond, Milton Babbitt, Frederic Rzewski, David Del Tredici, Conlon Nancarrow, Peter Maxwell Davies, George Tson- takis, Ellen Taaffe Zwilich, and many others. Roger Sessions: A Biography brings together considerable previously unpublished arch- ival material, such as letters, lectures, interviews, and articles, to shed light on the life and music of this major American composer. Andrea Olmstead, a teaching colleague of Sessions at Juilliard and the leading scholar on his music, has written a complete bio- graphy charting five touchstone areas through Sessions’s eighty-eight years: music, religion, politics, money, and sexuality. Andrea Olmstead, the author of Juilliard: A History, has published three books on Roger Sessions: Roger Sessions and His Music, Conversations with Roger Sessions, and The Correspondence of Roger Sessions. The author of numerous articles, reviews, program and liner notes, she is also a CD producer. This page intentionally left blank ROGER SESSIONS: A BIOGRAPHY Andrea Olmstead First published 2008 by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY, 10017, USA Simultaneously published in the UK by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2008 Andrea Olmstead Typeset in Garamond 3 by RefineCatch Limited, Bungay, Suffolk All rights reserved. -

Riders of the Purple Sage, Arizona Opera February & March 2017 As

Riders of the Purple Sage, Arizona Opera February & March 2017 As her helper, the gunslinger Lassiter, Morgan Smith gave us a stunning performance of a role in which the character’s personality gradually unfolds and grows in complexity. Maria Nockin, Opera Today, 7 March 2017 On opening night in Tucson, the lead roles of Jane and Lassiter were sung by soprano Karin Wolverton and baritone Morgan Smith, who both deliver memorable arias. Smith plays Lassiter with vintage Clint Eastwood menace as he growls out his provocative maxim, “A man without a gun is only half a man.” Kerry Lengel, Arizona Republic, 27 February 2017 Moby-Dick, Dallas Opera November 2016 Morgan Smith brings a dense, dark baritone to the role of Starbuck, the ship's voice of reason Scott Cantrell, Dallas News, 5 November 2016 Morgan Smith, who played Starbuck, gave a stunningly powerful performance in this scene, making the internal conflict in the character believable and real. Keith Cerny, Theater Jones, 6 December 2016 First Mate Starbuck is again sung by baritone Morgan Smith, who offers convincing muscularity and authority. J. Robin Coffelt, Texas Classical Review, 6 November 2016 Morgan Smith finely acted in the role of second in command, Starbuck, and his singing was even finer. When Starbuck attempts to dissuade Captain Ahab from his fool’s mission to wreck vengeance on the white whale, the audience was treated to the evening's most powerful and passionate singing — his duets with tenor Jay Hunter Morris as Ahab in particular. Monica Smart, Dallas Observer, 8 November 2016 Madama Butterfly, Kentucky Opera September 2016 With a diplomatic air and a rich, velvety baritone, he upheld the title of Consul and caretaker in a fatherly way. -

Now Again New Music Music by Bernard Rands Linda Reichert, Artistic Director Jan Krzywicki, Conductor with Guest Janice Felty, Mezzo-Soprano Now Again

Network for Now Again New Music Music by Bernard Rands Linda Reichert, Artistic Director Jan Krzywicki, Conductor with guest Janice Felty, mezzo-soprano Now Again Music by Bernard Rands Network for New Music Linda Reichert, Artistic Director Jan Krzywicki, Conductor www.albanyrecords.com TROY1194 albany records u.s. 915 broadway, albany, ny 12207 with guest Janice Felty, tel: 518.436.8814 fax: 518.436.0643 albany records u.k. box 137, kendal, cumbria la8 0xd mezzo-soprano tel: 01539 824008 © 2010 albany records made in the usa ddd waRning: cOpyrighT subsisTs in all Recordings issued undeR This label. The story is probably apocryphal, but it was said his students at Harvard had offered a prize to anyone finding a wantonly decorative note or gesture in any of Bernard Rands’ music. Small ensembles, single instrumental lines and tones convey implicitly Rands’ own inner, but arching, songfulness. In his recent songs, Rands has probed the essence of letter sounds, silence and stress in a daring voyage toward the center of a new world of dramatic, poetic expression. When he wrote “now again”—fragments from Sappho, sung here by Janice Felty, he was also A conversation between composer David Felder and filmmaker Elliot Caplan about Shamayim. refreshing his long association with the virtuosic instrumentalists of Network for New Music, the Philadelphia ensemble marking its 25th year in this recording. These songs were performed in a 2009 concert for Rands’ 75th birthday — and offer no hope for winning the prize for discovering extraneous notes or gestures. They offer, however, an intimate revelation of the composer’s grasp of color and shade, his joy in the pulsing heart, his thrill at the glimpse of what’s just ahead. -

An Analysis and Performance Considerations for John

AN ANALYSIS AND PERFORMANCE CONSIDERATIONS FOR JOHN HARBISON’S CONCERTO FOR OBOE, CLARINET, AND STRINGS by KATHERINE BELVIN (Under the Direction of D. RAY MCCLELLAN) ABSTRACT John Harbison is an award-winning and prolific American composer. He has written for almost every conceivable genre of concert performance with styles ranging from jazz to pre-classical forms. The focus of this study, his Concerto for Oboe, Clarinet, and Strings, was premiered in 1985 as a product of a Consortium Commission awarded by the National Endowment of the Arts. The initial discussions for the composition were with oboist Sara Bloom and clarinetist David Shifrin. Harbison’s Concerto for Oboe, Clarinet, and Strings allows the clarinet to finally be introduced to the concerto grosso texture of the Baroque period, for which it was born too late. This document includes biographical information on John Harbison including his life and career, compositional style, and compositional output. It also contains a brief history of the Baroque concerto grosso and how it relates to the Harbison concerto. There is a detailed set-class analysis of each movement and information on performance considerations. The two performers as well as the composer were interviewed to discuss the commission, premieres, and theoretical/performance considerations for the concerto. INDEX WORDS: John Harbison, Concerto for Oboe, Clarinet, and Strings, clarinet concerto, oboe concerto, Baroque concerto grosso, analysis and performance AN ANALYSIS AND PERFORMANCE CONSIDERATIONS FOR JOHN HARBISON’S CONCERTO FOR OBOE, CLARINET, AND STRINGS by KATHERINE BELVIN B.M., Tennessee Technological University, 2004 M.M., University of Cincinnati, 2006 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2009 © 2009 Katherine Belvin All Rights Reserved AN ANALYSIS AND PERFORMANCE CONSIDERATIONS FOR JOHN HARBISON’S CONCERTO FOR OBOE, CLARINET, AND STRINGS by KATHERINE BELVIN Major Professor: D. -

18AN1TEPO1 LV1 V01 Mars

BACCALAURÉAT TECHNOLOGIQUE SESSION 2018 ANGLAIS LV1 Séries : STI2D, STD2A, STL, ST2S Durée de l’épreuve : 2 heures - Coefficient : 2 Séries : STMG, STHR Durée de l’épreuve : 2 heures - Coefficient : 3 L’usage des calculatrices et de tout dictionnaire est interdit. Barème appliqué pour la correction TOUTES SÉRIES TECHNOLOGIQUES COMPRÉHENSION 10 points EXPRESSION 10 points Dès que le sujet est remis, assurez-vous qu’il est complet. Ce sujet comporte 6 pages numérotées de 1/6 à 6/6. 18AN1TEPO1 1/6 DOCUMENT 1 When the makers of Hollywood movies, documentary films, or TV news programs want to evoke the spirit of the 1960s, they typically show clips of long-haired hippies dancing at a festival, protestors marching at an antiwar rally, or students sitting-in at a lunch counter, with one of two songs by Bob Dylan—“Blowin’ in the Wind” or “The 5 Times They Are a-Changin’”—playing in the background. Journalists and historians often treat Dylan’s songs as emblematic of the era and Dylan himself as the quintessential “protest” singer, an image frozen in time. Dylan emerged on the music scene in 1961, playing in Greenwich Village coffeehouses after the folk music revival was already underway, and released his first album the next 10 year. Over a short period—less than three years—Dylan wrote about two dozen politically oriented songs whose creative lyrics and imagery reflected the changing mood of the postwar baby-boom generation and the urgency of the civil rights and antiwar movements. At a time when the chill of McCarthyism was still in the air, Dylan also showed that songs with leftist political messages could be commercially 15 successful. -

The Songs of Bob Dylan

The Songwriting of Bob Dylan Contents Dylan Albums of the Sixties (1960s)............................................................................................ 9 The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan (1963) ...................................................................................................... 9 1. Blowin' In The Wind ...................................................................................................................... 9 2. Girl From The North Country ....................................................................................................... 10 3. Masters of War ............................................................................................................................ 10 4. Down The Highway ...................................................................................................................... 12 5. Bob Dylan's Blues ........................................................................................................................ 13 6. A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall .......................................................................................................... 13 7. Don't Think Twice, It's All Right ................................................................................................... 15 8. Bob Dylan's Dream ...................................................................................................................... 15 9. Oxford Town ............................................................................................................................... -

Still on the Road 1990 Us Fall Tour

STILL ON THE ROAD 1990 US FALL TOUR OCTOBER 11 Brookville, New York Tilles Center, C.W. Post College 12 Springfield, Massachusetts Paramount Performing Arts Center 13 West Point, New York Eisenhower Hall Theater 15 New York City, New York The Beacon Theatre 16 New York City, New York The Beacon Theatre 17 New York City, New York The Beacon Theatre 18 New York City, New York The Beacon Theatre 19 New York City, New York The Beacon Theatre 21 Richmond, Virginia Richmond Mosque 22 Pittsburg, Pennsylvania Syria Mosque 23 Charleston, West Virginia Municipal Auditorium 25 Oxford, Mississippi Ted Smith Coliseum, University of Mississippi 26 Tuscaloosa, Alabama Coleman Coliseum 27 Nashville, Tennessee Memorial Hall, Vanderbilt University 28 Athens, Georgia Coliseum, University of Georgia 30 Boone, North Carolina Appalachian State College, Varsity Gymnasium 31 Charlotte, North Carolina Ovens Auditorium NOVEMBER 2 Lexington, Kentucky Memorial Coliseum 3 Carbondale, Illinois SIU Arena 4 St. Louis, Missouri Fox Theater 6 DeKalb, Illinois Chick Evans Fieldhouse, University of Northern Illinois 8 Iowa City, Iowa Carver-Hawkeye Auditorium 9 Chicago, Illinois Fox Theater 10 Milwaukee, Wisconsin Riverside Theater 12 East Lansing, Michigan Wharton Center, University of Michigan 13 Dayton, Ohio University of Dayton Arena 14 Normal, Illinois Brayden Auditorium 16 Columbus, Ohio Palace Theater 17 Cleveland, Ohio Music Hall 18 Detroit, Michigan The Fox Theater Bob Dylan 1990: US Fall Tour 11530 Rose And Gilbert Tilles Performing Arts Center C.W. Post College, Long Island University Brookville, New York 11 October 1990 1. Marines' Hymn (Jacques Offenbach) 2. Masters Of War 3. Tomorrow Is A Long Time 4. -

Music with Heart.Pdf

Wonderful Life 2018 insert.qxp_IAWL 2018 11/5/18 8:07 PM Page 1 B Y E DWARD S ECKERSON usic M with Heart American opera is alive and well in the imagination of Jake Heggie LMOND A AREN K 40 SAN FRANCISCO OPERA Wonderful Life 2018 insert.qxp_IAWL 2018 11/5/18 8:07 PM Page 2 n the multifaceted world of music theater, opera has true only to himself and that his unapologetic fondness for and always occupied the higher ground. It’s almost as if love of the American stage at its most lyric would dictate how he the very word has served to elevate the form and would write, in the only way he knew how: tonally, gratefully, gen- willfully set it apart from that branch of the genre where characters erously, from the heart. are wont to speak as well as sing: the musical. But where does Dissenting voices have accused him of not pushing the enve- thatI leave Bizet’s Carmen or Mozart’s Magic Flute? And why is it lope, of rejoicing in the past and not the future, of veering too so hard to accept that music theater comes in a great many forms close to Broadway (as if that were a bad thing) and courting popu- and styles and that through-sung or not, there are stories to be lar appeal. But where Bernstein, it could be argued, spent too told in words and music and more than one way to tell them? Will much precious time quietly seeking the approval of his cutting- there ever be an end to the tedious debate as to whether Stephen edge contemporaries (with even a work like A Quiet Place betray- Sondheim’s Sweeney Todd or Leonard Bernstein’s Candide are ing a certain determination to toughen up his act), Heggie has musicals or operas? Both scores are inherently “operatic” for written only the music he wanted—needed—to write. -

An Interview with Jake Heggie

35 Mediterranean Opera and Ballet Club Culture and Art Magazine A Chat with Composer Jake Heggie Besteci Jake Heggie İle Bir Sohbet Othello in the Dansa Âşık Bir Kuğu: Seraglio Meriç Sümen Othello Sarayda FLÜTİST HALİT TURGAY Fotoğraf: Mehmet Çağlarer A Chat with Jake Heggie Composer Jake Heggie (Photo by Art & Clarity). (Photo by Heggie Composer Jake Besteci Jake Heggie İle Bir Sohbet Ömer Eğecioğlu Santa Barbara, CA, ABD [email protected] 6 AKOB | NİSAN 2016 San Francisco-based American composer Jake Heggie is the author of upwards of 250 Genç Amerikalı besteci Jake Heggie şimdiye art songs. Some of his work in this genre were recorded by most notable artists of kadar 250’den fazla şarkıya imzasını atmış our time: Renée Fleming, Frederica von Stade, Carol Vaness, Joyce DiDonato, Sylvia bir müzisyen. Üstelik bu şarkılar günümüzün McNair and others. He has also written choral, orchestral and chamber works. But en ünlü ses sanatçıları tarafından yorumlanıp most importantly, Heggie is an opera composer. He is one of the most notable of the kaydedilmiş: Renée Fleming, Frederica von younger generation of American opera composers alongside perhaps Tobias Picker Stade, Carol Vaness, Joyce DiDonato, Sylvia and Ricky Ian Gordon. In fact, Heggie is considered by many to be simply the most McNair bu sanatçıların arasında yer alıyor. Heggie’nin diğer eserleri arasında koro ve successful living American composer. orkestra için çalışmalar ve ayrıca oda müziği parçaları var. Ama kendisi en başta bir opera Heggie’s recognition as an opera composer came in 2000 with Dead Man Walking, bestecisi olarak tanınıyor. Jake Heggie’nin with libretto by Terrence McNally, based on the popular book by Sister Helen Préjean. -

SF Opera Guild Virtual Event April 28.Pdf

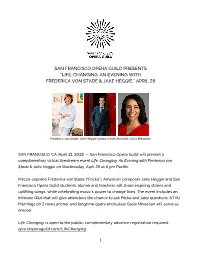

SAN FRANCISCO OPERA GUILD PRESENTS “LIFE. CHANGING. AN EVENING WITH FREDERICA VON STADE & JAKE HEGGIE,” APRIL 28 Frederica von Stade; Jake Heggie (photo: Karen Almond); Gasia Mikaelian SAN FRANCISCO, CA (April 21, 2021) — San Francisco Opera Guild will present a complimentary virtual livestream event Life. Changing. An Evening with Frederica von Stade & Jake Heggie on Wednesday, April 28 at 6 pm Pacific. Mezzo-soprano Frederica von Stade (“Flicka”), American composer Jake Heggie and San Francisco Opera Guild students, alumni and teachers will share inspiring stories and uplifting songs, while celebrating music’s power to change lives. The event includes an intimate Q&A that will give attendees the chance to ask Flicka and Jake questions. KTVU Mornings on 2 news anchor and longtime opera enthusiast Gasia Mikaelian will serve as emcee. Life. Changing. is open to the public; complimentary advance registration required: give.sfoperaguild.com/LifeChanging. 1 Frederica von Stade said: “I love being with my pal, the wonderful Jake Heggie, to celebrate the great efforts of San Francisco Opera Guild in reaching out to the young people of the Bay Area. It means so much to me because I know firsthand of these efforts and have seen the amazing results. I applaud the Guild’s Director of Education Caroline Altman and her work with the Opera Scouts and the amazing team at the Guild. Music changed my life, and I’m excited to celebrate how it changes the lives of our precious young people.” Jake Heggie said: “I'm delighted to join with my great friend Frederica von Stade to spotlight the important, ongoing work in music education made possible by San Francisco Opera Guild.