"An Alphabet of Soldiers”: Jake Heggie's Farewell, Auschwitz

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

L'opéra Moby Dick De Jake Heggie

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 20 | 2020 Staging American Nights L’opéra Moby Dick de Jake Heggie : de nouveaux enjeux de représentation pour l’œuvre d’Herman Melville Nathalie Massoulier Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/26739 DOI : 10.4000/miranda.26739 ISSN : 2108-6559 Éditeur Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Référence électronique Nathalie Massoulier, « L’opéra Moby Dick de Jake Heggie : de nouveaux enjeux de représentation pour l’œuvre d’Herman Melville », Miranda [En ligne], 20 | 2020, mis en ligne le 20 avril 2020, consulté le 16 février 2021. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/26739 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/ miranda.26739 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 16 février 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. L’opéra Moby Dick de Jake Heggie : de nouveaux enjeux de représentation pour ... 1 L’opéra Moby Dick de Jake Heggie : de nouveaux enjeux de représentation pour l’œuvre d’Herman Melville Nathalie Massoulier Le moment où une situation mythologique réapparaît est toujours caractérisé par une intensité émotionnelle spéciale : tout se passe comme si quelque chose résonnait en nous qui n’avait jamais résonné auparavant ou comme si certaines forces demeurées jusque-là insoupçonnées se mettaient à se déchaîner […], en de tels moments, nous n’agissons plus en tant qu’individus mais en tant que race, c’est la voix de l’humanité tout entière qui se fait entendre en nous, […] une voix plus puissante que la nôtre propre est invoquée. -

Riders of the Purple Sage, Arizona Opera February & March 2017 As

Riders of the Purple Sage, Arizona Opera February & March 2017 As her helper, the gunslinger Lassiter, Morgan Smith gave us a stunning performance of a role in which the character’s personality gradually unfolds and grows in complexity. Maria Nockin, Opera Today, 7 March 2017 On opening night in Tucson, the lead roles of Jane and Lassiter were sung by soprano Karin Wolverton and baritone Morgan Smith, who both deliver memorable arias. Smith plays Lassiter with vintage Clint Eastwood menace as he growls out his provocative maxim, “A man without a gun is only half a man.” Kerry Lengel, Arizona Republic, 27 February 2017 Moby-Dick, Dallas Opera November 2016 Morgan Smith brings a dense, dark baritone to the role of Starbuck, the ship's voice of reason Scott Cantrell, Dallas News, 5 November 2016 Morgan Smith, who played Starbuck, gave a stunningly powerful performance in this scene, making the internal conflict in the character believable and real. Keith Cerny, Theater Jones, 6 December 2016 First Mate Starbuck is again sung by baritone Morgan Smith, who offers convincing muscularity and authority. J. Robin Coffelt, Texas Classical Review, 6 November 2016 Morgan Smith finely acted in the role of second in command, Starbuck, and his singing was even finer. When Starbuck attempts to dissuade Captain Ahab from his fool’s mission to wreck vengeance on the white whale, the audience was treated to the evening's most powerful and passionate singing — his duets with tenor Jay Hunter Morris as Ahab in particular. Monica Smart, Dallas Observer, 8 November 2016 Madama Butterfly, Kentucky Opera September 2016 With a diplomatic air and a rich, velvety baritone, he upheld the title of Consul and caretaker in a fatherly way. -

Fond Affection Music of Ernst Bacon

NWCR890 Fond Affection Music of Ernst Bacon Baritone Songs: Settings of poems by Walt Whitman (8-12); Carl Sandburg (13); Emily Dickinson (14-15); A.E. Housman (16); and Ernst Bacon (17). 8. The Commonplace ................................... (1:05) 9. Grand Is the Seen ..................................... (2:48) 10. Lingering Last Drops ............................... (1:57) 11. The Last Invocation .................................. (2:23) 12. The Divine Ship ....................................... (1:04) 13. Omaha ...................................................... (1:29) 14. It’s coming—the postponeless Creature ... (2:36) 15. How Still the bells .................................... (2:01) 16. Farewell to a name and a number ............. (1:28) 17. Brady ........................................................ (2:07) William Sharp, baritone; John Musto, piano Soprano Songs: Settings of poems by Emily Dickinson (18- 21); William Blake (22); 17th-century English text (23); Cho Wen-chun, tr. Arthur Waley (24); and Helena Carus (25) 18. It’s All I Have To Bring ........................... (1:16) 19. Velvet People ........................................... (1:37) 20. The Bat ..................................................... (1:56) 21. Wild Nights .............................................. (1:18) 22. The Lamb ................................................. (2:43) 23. Little Boy ................................................. (2:42) 24. Song of Snow-white Heads ...................... (2:35) 25. A Brighter Morning ................................. -

Three Decembers” STARRING WORLD-RENOWNED MEZZO SOPRANO SUSAN GRAHAM and CELEBRATED ARTISTS MAYA KHERANI and EFRAÍN SOLÍS Available Via Online Streaming Anytime

OPERA SAN JOSÉ EXTENDS ACCESS TO VIRTUAL PERFORMANCE OF Jake Heggie’s “Three Decembers” STARRING WORLD-RENOWNED MEZZO SOPRANO SUSAN GRAHAM AND CELEBRATED ARTISTS MAYA KHERANI AND EFRAÍN SOLÍS Available via online streaming anytime SAN JOSE, CA (3 February 2021) – In keeping with Opera San José’s mission to expand accessibility to its work, the company has announced that through the support of generous donors it is able to extend access to its hit virtual production of Jake Heggie’s chamber opera, Three Decembers, now making it available on a pay-what-you-can basis for streaming on demand. The production is being offered with subtitles in Spanish and Vietnamese, as well as English, furthering its accessibility to the Spanish and Vietnamese speaking members of the San Jose community, two of the largest populations in its home region. Featuring world-renowned mezzo-soprano Susan Graham in the central role, alongside celebrated Opera San José Resident Artists soprano Maya Kherani and baritone Efraín Solís, this world-class digital production has been met with widespread critical acclaim. Based on an unpublished play by Tony Award winning playwright Terrence McNally, Three Decembers follows the riveting story of a famous stage actress and her two adult children, struggling to connect over three decades, as long-held secrets come to light. With a brilliant, witty libretto by Gene Scheer and a soaring musical score by Jake Heggie, Three Decembers offers a 90-minute fullhearted American opera about family – the ones we are born into and those we create. Tickets for the modern work, which was recorded last Fall in the company’s Heiman Digital Media Studio, are pay-what-you-can beginning at $15 per household, which includes on-demand streaming for 30 days after date of purchase. -

The Inventory of the Phyllis Curtin Collection #1247

The Inventory of the Phyllis Curtin Collection #1247 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center Phyllis Curtin - Box 1 Folder# Title: Photographs Folder# F3 Clothes by Worth of Paris (1900) Brooklyn Academy F3 F4 P.C. recording F4 F7 P. C. concert version Rosenkavalier Philadelphia F7 FS P.C. with Russell Stanger· FS F9 P.C. with Robert Shaw F9 FIO P.C. with Ned Rorem Fl0 F11 P.C. with Gerald Moore Fl I F12 P.C. with Andre Kostelanetz (Promenade Concerts) F12 F13 P.C. with Carlylse Floyd F13 F14 P.C. with Family (photo of Cooke photographing Phyllis) FI4 FIS P.C. with Ryan Edwards (Pianist) FIS F16 P.C. with Aaron Copland (televised from P.C. 's home - Dickinson Songs) F16 F17 P.C. with Leonard Bernstein Fl 7 F18 Concert rehearsals Fl8 FIS - Gunther Schuller Fl 8 FIS -Leontyne Price in Vienna FIS F18 -others F18 F19 P.C. with hairdresser Nina Lawson (good backstage photo) FI9 F20 P.C. with Darius Milhaud F20 F21 P.C. with Composers & Conductors F21 F21 -Eugene Ormandy F21 F21 -Benjamin Britten - Premiere War Requiem F2I F22 P.C. at White House (Fords) F22 F23 P.C. teaching (Yale) F23 F25 P.C. in Tel Aviv and U.N. F25 F26 P. C. teaching (Tanglewood) F26 F27 P. C. in Sydney, Australia - Construction of Opera House F27 F2S P.C. in Ipswich in Rehearsal (Castle Hill?) F2S F28 -P.C. in Hamburg (large photo) F2S F30 P.C. in Hamburg (Strauss I00th anniversary) F30 F31 P. C. in Munich - German TV F31 F32 P.C. -

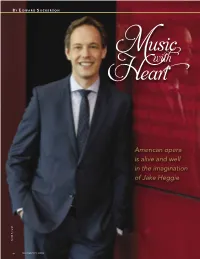

Music with Heart.Pdf

Wonderful Life 2018 insert.qxp_IAWL 2018 11/5/18 8:07 PM Page 1 B Y E DWARD S ECKERSON usic M with Heart American opera is alive and well in the imagination of Jake Heggie LMOND A AREN K 40 SAN FRANCISCO OPERA Wonderful Life 2018 insert.qxp_IAWL 2018 11/5/18 8:07 PM Page 2 n the multifaceted world of music theater, opera has true only to himself and that his unapologetic fondness for and always occupied the higher ground. It’s almost as if love of the American stage at its most lyric would dictate how he the very word has served to elevate the form and would write, in the only way he knew how: tonally, gratefully, gen- willfully set it apart from that branch of the genre where characters erously, from the heart. are wont to speak as well as sing: the musical. But where does Dissenting voices have accused him of not pushing the enve- thatI leave Bizet’s Carmen or Mozart’s Magic Flute? And why is it lope, of rejoicing in the past and not the future, of veering too so hard to accept that music theater comes in a great many forms close to Broadway (as if that were a bad thing) and courting popu- and styles and that through-sung or not, there are stories to be lar appeal. But where Bernstein, it could be argued, spent too told in words and music and more than one way to tell them? Will much precious time quietly seeking the approval of his cutting- there ever be an end to the tedious debate as to whether Stephen edge contemporaries (with even a work like A Quiet Place betray- Sondheim’s Sweeney Todd or Leonard Bernstein’s Candide are ing a certain determination to toughen up his act), Heggie has musicals or operas? Both scores are inherently “operatic” for written only the music he wanted—needed—to write. -

An Interview with Jake Heggie

35 Mediterranean Opera and Ballet Club Culture and Art Magazine A Chat with Composer Jake Heggie Besteci Jake Heggie İle Bir Sohbet Othello in the Dansa Âşık Bir Kuğu: Seraglio Meriç Sümen Othello Sarayda FLÜTİST HALİT TURGAY Fotoğraf: Mehmet Çağlarer A Chat with Jake Heggie Composer Jake Heggie (Photo by Art & Clarity). (Photo by Heggie Composer Jake Besteci Jake Heggie İle Bir Sohbet Ömer Eğecioğlu Santa Barbara, CA, ABD [email protected] 6 AKOB | NİSAN 2016 San Francisco-based American composer Jake Heggie is the author of upwards of 250 Genç Amerikalı besteci Jake Heggie şimdiye art songs. Some of his work in this genre were recorded by most notable artists of kadar 250’den fazla şarkıya imzasını atmış our time: Renée Fleming, Frederica von Stade, Carol Vaness, Joyce DiDonato, Sylvia bir müzisyen. Üstelik bu şarkılar günümüzün McNair and others. He has also written choral, orchestral and chamber works. But en ünlü ses sanatçıları tarafından yorumlanıp most importantly, Heggie is an opera composer. He is one of the most notable of the kaydedilmiş: Renée Fleming, Frederica von younger generation of American opera composers alongside perhaps Tobias Picker Stade, Carol Vaness, Joyce DiDonato, Sylvia and Ricky Ian Gordon. In fact, Heggie is considered by many to be simply the most McNair bu sanatçıların arasında yer alıyor. Heggie’nin diğer eserleri arasında koro ve successful living American composer. orkestra için çalışmalar ve ayrıca oda müziği parçaları var. Ama kendisi en başta bir opera Heggie’s recognition as an opera composer came in 2000 with Dead Man Walking, bestecisi olarak tanınıyor. Jake Heggie’nin with libretto by Terrence McNally, based on the popular book by Sister Helen Préjean. -

SF Opera Guild Virtual Event April 28.Pdf

SAN FRANCISCO OPERA GUILD PRESENTS “LIFE. CHANGING. AN EVENING WITH FREDERICA VON STADE & JAKE HEGGIE,” APRIL 28 Frederica von Stade; Jake Heggie (photo: Karen Almond); Gasia Mikaelian SAN FRANCISCO, CA (April 21, 2021) — San Francisco Opera Guild will present a complimentary virtual livestream event Life. Changing. An Evening with Frederica von Stade & Jake Heggie on Wednesday, April 28 at 6 pm Pacific. Mezzo-soprano Frederica von Stade (“Flicka”), American composer Jake Heggie and San Francisco Opera Guild students, alumni and teachers will share inspiring stories and uplifting songs, while celebrating music’s power to change lives. The event includes an intimate Q&A that will give attendees the chance to ask Flicka and Jake questions. KTVU Mornings on 2 news anchor and longtime opera enthusiast Gasia Mikaelian will serve as emcee. Life. Changing. is open to the public; complimentary advance registration required: give.sfoperaguild.com/LifeChanging. 1 Frederica von Stade said: “I love being with my pal, the wonderful Jake Heggie, to celebrate the great efforts of San Francisco Opera Guild in reaching out to the young people of the Bay Area. It means so much to me because I know firsthand of these efforts and have seen the amazing results. I applaud the Guild’s Director of Education Caroline Altman and her work with the Opera Scouts and the amazing team at the Guild. Music changed my life, and I’m excited to celebrate how it changes the lives of our precious young people.” Jake Heggie said: “I'm delighted to join with my great friend Frederica von Stade to spotlight the important, ongoing work in music education made possible by San Francisco Opera Guild. -

Emily Dickinson in Song

1 Emily Dickinson in Song A Discography, 1925-2019 Compiled by Georgiana Strickland 2 Copyright © 2019 by Georgiana W. Strickland All rights reserved 3 What would the Dower be Had I the Art to stun myself With Bolts of Melody! Emily Dickinson 4 Contents Preface 5 Introduction 7 I. Recordings with Vocal Works by a Single Composer 9 Alphabetical by composer II. Compilations: Recordings with Vocal Works by Multiple Composers 54 Alphabetical by record title III. Recordings with Non-Vocal Works 72 Alphabetical by composer or record title IV: Recordings with Works in Miscellaneous Formats 76 Alphabetical by composer or record title Sources 81 Acknowledgments 83 5 Preface The American poet Emily Dickinson (1830-1886), unknown in her lifetime, is today revered by poets and poetry lovers throughout the world, and her revolutionary poetic style has been widely influential. Yet her equally wide influence on the world of music was largely unrecognized until 1992, when the late Carlton Lowenberg published his groundbreaking study Musicians Wrestle Everywhere: Emily Dickinson and Music (Fallen Leaf Press), an examination of Dickinson's involvement in the music of her time, and a "detailed inventory" of 1,615 musical settings of her poems. The result is a survey of an important segment of twentieth-century music. In the years since Lowenberg's inventory appeared, the number of Dickinson settings is estimated to have more than doubled, and a large number of them have been performed and recorded. One critic has described Dickinson as "the darling of modern composers."1 The intriguing question of why this should be so has been answered in many ways by composers and others. -

![[Sample Title Page]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7574/sample-title-page-1017574.webp)

[Sample Title Page]

ART SONGS OF WILLIAM GRANT STILL by Juliet Gilchrist Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University May 2020 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee ______________________________________ Luke Gillespie, Research Director ______________________________________ Mary Ann Hart, Chair ______________________________________ Patricia Havranek ______________________________________ Marietta Simpson January 27, 2020 ii To my mom and dad, who have given me everything: teaching me about music, how to serve others, and, most importantly, eternal principles. Thank you for always being there. iii Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................ iv List of Examples .............................................................................................................................. v List of Figures ................................................................................................................................. vi Chapter 1: Introduction .................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 2: Childhood influences and upbringing ............................................................................ 5 Chapter 3: Still, -

Download the Closing Recital Program Notes and Artist Bios

Closing Recital: The Music of (Un)told Stories Thursday, March 14 at 5 PM Colton Recital Hall, Fine Arts Building Program Notes Romance for Violin and Piano, Op. 24 Amy Beach (1867–1944) Dr. Ioana Galu, violin Dr. Susan Keith Gray, piano Amy Beach was arguably the earliest and most prominent American woman composer, becoming a leading representative of the late 19th century Romantic style. She was largely a self-taught composer and never studied abroad. As a child prodigy, she taught herself to read at the age of three and composed mentally several piano pieces at the age of four. She studied piano with her mother, and then with Ernst Perabo, debuting as a concert pianist at sixteen. After her marriage to the famous Boston surgeon Dr. H.H. A. Beach, she limited her solo concerts to charity events and focused all her energy to composing. She returned to professional public performances after the death of her husband in 1910, touring Europe and the US. She dedicated the “Romance” to the prestigious American violinist Maud Powell, and they premiered it together on July 6th 1893 during the World’s Columbian Exposition. The audience cheered enthusiastically at the conclusion of the piece, so much they had to repeat it. About that day, Maud Powell reminisced: “Our meeting in Chicago and the pleasure of playing together made a most delightful episode in my Summer’s experience. I trust it soon may be repeated.” Source: ALS Maud Powell to Amy Beach, 6 December 1993, Special Collections, University of New Hampshire Library. Iconic Legacies: First Ladies at the Smithsonian (Scheer) Jake Heggie (b. -

Nov-Dec 2020

THE EMILY DICKINSON INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY Volume 32, Number 2 November/December 2020 “The Only News I know / Is Bulletins all Day / From Immortality.” Puuseppä, itseoppinut Posant mes pas de Planche en Planche olin – jo aikani J’allais mon lent et prudent chemin höyläni kanssa puuhannut Ma Tête semblait environnee d’ Etoiles kun saapui mestari Et mes pieds baignés d’Océan – mittaamaan työtä: oliko Je ne savais pas si le prochain ammattitaitonne Serait ou non mon dernier pas – riittävä - jos, hän palkkaisi Cela me donnait cette précaire Allure puoliksi kummankin Que d’aucuns nomment l’Expérience – Työkalut kasvot ihmisen sai – höyläpenkkikin todisti toisin: rakentaa osamme temppelit! Me áta – canto mesmo assim Proíbe – meu bandolim – Jag aldrig sett en hed. Toca dentro, de mim – Jag aldrig sett havet – men vet ändå hur ljung ser ut Me mata – e a Alma flutua och vad en bölja är – Cantando ao Paraíso – Зашла купить улыбку – раз – Sou Tua – Всего-то лишь одну – Jag aldrig talat med Gud, Что на щеке, но вскользь у Вас - i himlen aldrig gjort visit – Да только мне к Лицу – men vet lika säkert var den är Ту, без которй нет потерь som om jag ägt biljett – Слаба она сиять – Молю, Сэр, подсчитать – её Смогли бы вы продать? 你知道我看不到你的人生 – Алмазы – на моих перстах! Вам ли не знать, о да! 我须猜测 – Рубины – словно Кровь, горят – 多少次这让我痛苦 – 今天承认 – Топазы – как звезда! Еврею торг такой в пример! 多少次为了我的远大前程 Что скажите мне – Сэр? 那勇敢的双眼悲痛迷蒙 – 但我估摸呀猜测令人伤心 – 我的眼啊 – 已模糊不清! Officers President: Elizabeth Petrino Vice-President: Eliza Richards Secretary: Adeline Chevrier-Bosseau Treasurer: James C. Fraser Board Members Renée Bergland Páraic Finnerty Elizabeth Petrino George Boziwick James C.