Testimony of Jack L. Warner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The River Jordan Pours Its ; with the Nr Water Into Lake Tiberias, Which Is Wholly Within Lsrael

f\o t! .* :: "h*-"F*. l: a $* $ WI 4 .t' THE RIVER * JORDAN {+1 t.{ t* !d. J tl & I J E* It & INTRODIiCTION { it /4 & CI resources is one of tlle Itlost cltrracleristic features o[ the f iSao*a,r" of waler x the. Palestine li{andate entrusted to Britain $ t*rrain that wh to constitute the area of r, rltcr \Vorld War I. Rain falls only in the short winter, leaving a long dry summer when T countries to the north tt qricultuie depends entirely orr irrigation. The neighbouring t :. have abundant resources for irrigation, Syria sharin! the Euplrrates with {*iri} and rhe s pu1.51ins rr/as -€ A"r,* *iti, Lebanbrt, and l.ebanon endole.J, besides, with t]re Litani- I to be dependent 'almost entirel.v on the exigtrcus Jordan. Tiierefo:e, when lhe rt * boundaries of Palestine werc to be setticci aftcr lYarld War l, Britaiu' as the prcspective 5 ll:ndatory Power, and the Zionist Organizati,:n representing'the nascent Jewish * Igfonal Home, demanded that the Jordan and all its iribuiaries be includeC in their Palcstine and tlr-at tl-re Litani demarcate Palestine's northern * iniiiety in the territory of { fruntier. But, at French insistence, Paiestine's no:thern bor:ndary with Lebanon and * Syria, both placed under French l{andate, was set southof the Litani andle.stof {t' 3.: ilennon, sO that three of the four ntain tributaries of the Jordan - the Hasbani' the Baaias and the Yarmuk -. were to originate in French-Mandated territories, and the Urani would become a Lebanese nationai river. -

PAPERS of the NAACP Part Segregation and Discrimination, 15 Complaints and Responses, 1940-1955

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of BLACK STUDIES RESEARCH SOURCES Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editors: John H. Bracey, Jr. and August Meier PAPERS OF THE NAACP Part Segregation and Discrimination, 15 Complaints and Responses, 1940-1955 Series B: Administrative Files UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA PAPERS OF THE NAACP Part 15. Segregation and Discrimination, Complaints and Responses, 1940-1955 Series B: Administrative Files A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of BLACK STUDIES RESEARCH SOURCES Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editors: John H. Bracey, Jr. and August Meier PAPERS OF THE NAACP Part 15. Segregation and Discrimination, Complaints and Responses, 1940-1955 Series B: Administrative Files Edited by John H. Bracey, Jr. and August Meier Project Coordinator Randolph Boehm Guide compiled by Martin Schipper A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway * Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloglng-ln-Publication Data National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Papers of the NAACP. [microform] Accompanied by printed reel guides. Contents: pt. 1. Meetings of the Board of Directors, records of annual conferences, major speeches, and special reports, 1909-1950 / editorial adviser, August Meier; edited by Mark Fox--pt. 2. Personal correspondence of selected NAACP officials, 1919-1939 / editorial--[etc.]--pt. 15. Segregation and discrimination, complaints and responses, 1940-1955. 1. National Association for the Advancement of Colored People-Archives. 2. Afro-Americans--Civil Rights--History--20th century-Sources. 3. Afro- Americans--History--1877-1964--Sources. 4. United States--Race relations-Sources. I. Meier, August, 1923- . -

The Creative Process

The Creative Process THE SEARCH FOR AN AUDIO-VISUAL LANGUAGE AND STRUCTURE SECOND EDITION by John Howard Lawson Preface by Jay Leyda dol HILL AND WANG • NEW YORK www.johnhowardlawson.com Copyright © 1964, 1967 by John Howard Lawson All rights reserved Library of Congress catalog card number: 67-26852 Manufactured in the United States of America First edition September 1964 Second edition November 1967 www.johnhowardlawson.com To the Association of Film Makers of the U.S.S.R. and all its members, whose proud traditions and present achievements have been an inspiration in the preparation of this book www.johnhowardlawson.com Preface The masters of cinema moved at a leisurely pace, enjoyed giving generalized instruction, and loved to abandon themselves to reminis cence. They made it clear that they possessed certain magical secrets of their profession, but they mentioned them evasively. Now and then they made lofty artistic pronouncements, but they showed a more sincere interest in anecdotes about scenarios that were written on a cuff during a gay supper.... This might well be a description of Hollywood during any period of its cultivated silence on the matter of film-making. Actually, it is Leningrad in 1924, described by Grigori Kozintsev in his memoirs.1 It is so seldom that we are allowed to study the disclosures of a Hollywood film-maker about his medium that I cannot recall the last instance that preceded John Howard Lawson's book. There is no dearth of books about Hollywood, but when did any other book come from there that takes such articulate pride in the art that is-or was-made there? I have never understood exactly why the makers of American films felt it necessary to hide their methods and aims under blankets of coyness and anecdotes, the one as impenetrable as the other. -

Expressionism and Modernism in the American Theatre: Bodies, Voices, Words Julia A

Cambridge University Press 0521847478 - Expressionism and Modernism in the American Theatre: Bodies, Voices, Words Julia A. Walker Frontmatter More information Expressionism and Modernism in the American Theatre Although often dismissed as a minor offshoot of the better-known German movement, expressionism on the American stage represents a critical phase in the development of American dramatic modernism. Situating expressionism within the context of early twentieth-century American culture, Walker demonstrates how playwrights who wrote in this mode were responding both to new communica- tions technologies and to the perceived threat they posed to the embodied act of meaning. At a time when mute bodies gesticulated on the silver screen, ghostly voices emanated from tin horns, and inked words stamped out the personality of the hand that composed them, expressionist playwrights began to represent these new cultural experiences by disarticulating the theatrical languages of bodies, voices, and words. In doing so, they not only innovated a new dramatic form, but re- defined playwriting from a theatrical craft to a literary art form, heralding the birth of American dramatic modernism. julia a. walker is Assistant Professor of English and the Unit for Criticism and Interpretive Theory,University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. She has published articles in the Journal of American Drama and Theatre, Nineteenth Century Theatre, and the Yale Journal of Criticism in addition to several edited volumes. © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521847478 - Expressionism and Modernism in the American Theatre: Bodies, Voices, Words Julia A. Walker Frontmatter More information CAMBRIDGE STUDIES IN AMERICAN THEATRE AND DRAMA General Editor Don B. -

Violence and Masculinity in Hollywood War Films During World War II a Thesis Submitted To

Violence and Masculinity in Hollywood War Films During World War II A thesis submitted to: Lakehead University Faculty of Arts and Sciences Department of History In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree in Master of Arts Matthew Sitter Thunder Bay, Ontario July 2012 Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-84504-2 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-84504-2 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l'Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriété du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette thèse. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Bruce Walker Musical Theater Recording Collection

Bruce Walker Musical Theater Recording Collection Bruce Walker Musical Theater Recording Collection Recordings are on vinyl unless marked otherwise marked (* = Cassette or # = Compact Disc) KEY OC - Original Cast TV - Television Soundtrack OBC - Original Broadway Cast ST - Film Soundtrack OLC - Original London Cast SC - Studio Cast RC - Revival Cast ## 2 (OC) 3 GUYS NAKED FROM THE WAIST DOWN (OC) 4 TO THE BAR 13 DAUGHTERS 20'S AND ALL THAT JAZZ, THE 40 YEARS ON (OC) 42ND STREET (OC) 70, GIRLS, 70 (OC) 81 PROOF 110 IN THE SHADE (OC) 1776 (OC) A A5678 - A MUSICAL FABLE ABSENT-MINDED DRAGON, THE ACE OF CLUBS (SEE NOEL COWARD) ACROSS AMERICA ACT, THE (OC) ADVENTURES OF BARON MUNCHHAUSEN, THE ADVENTURES OF COLORED MAN ADVENTURES OF MARCO POLO (TV) AFTER THE BALL (OLC) AIDA AIN'T MISBEHAVIN' (OC) AIN'T SUPPOSED TO DIE A NATURAL DEATH ALADD/THE DRAGON (BAG-A-TALE) Bruce Walker Musical Theater Recording Collection ALADDIN (OLC) ALADDIN (OC Wilson) ALI BABBA & THE FORTY THIEVES ALICE IN WONDERLAND (JANE POWELL) ALICE IN WONDERLAND (ANN STEPHENS) ALIVE AND WELL (EARL ROBINSON) ALLADIN AND HIS WONDERFUL LAMP ALL ABOUT LIFE ALL AMERICAN (OC) ALL FACES WEST (10") THE ALL NIGHT STRUT! ALICE THROUGH THE LOOKING GLASS (TV) ALL IN LOVE (OC) ALLEGRO (0C) THE AMAZING SPIDER-MAN AMBASSADOR AMERICAN HEROES AN AMERICAN POEM AMERICANS OR LAST TANGO IN HUAHUATENANGO .....................(SF MIME TROUPE) (See FACTWINO) AMY THE ANASTASIA AFFAIRE (CD) AND SO TO BED (SEE VIVIAN ELLIS) AND THE WORLD GOES 'ROUND (CD) AND THEN WE WROTE... (FLANDERS & SWANN) AMERICAN -

ABSTRACT Title of Document: from the BELLY of the HUAC: the RED PROBES of HOLLYWOOD, 1947-1952 Jack D. Meeks, Doctor of Philos

ABSTRACT Title of Document: FROM THE BELLY OF THE HUAC: THE RED PROBES OF HOLLYWOOD, 1947-1952 Jack D. Meeks, Doctor of Philosophy, 2009 Directed By: Dr. Maurine Beasley, Journalism The House Un-American Activities Committee, popularly known as the HUAC, conducted two investigations of the movie industry, in 1947 and again in 1951-1952. The goal was to determine the extent of communist infiltration in Hollywood and whether communist propaganda had made it into American movies. The spotlight that the HUAC shone on Tinsel Town led to the blacklisting of approximately 300 Hollywood professionals. This, along with the HUAC’s insistence that witnesses testifying under oath identify others that they knew to be communists, contributed to the Committee’s notoriety. Until now, historians have concentrated on offering accounts of the HUAC’s practice of naming names, its scrutiny of movies for propaganda, and its intervention in Hollywood union disputes. The HUAC’s sealed files were first opened to scholars in 2001. This study is the first to draw extensively on these newly available documents in an effort to reevaluate the HUAC’s Hollywood probes. This study assesses four areas in which the new evidence indicates significant, fresh findings. First, a detailed analysis of the Committee’s investigatory methods reveals that most of the HUAC’s information came from a careful, on-going analysis of the communist press, rather than techniques such as surveillance, wiretaps and other cloak and dagger activities. Second, the evidence shows the crucial role played by two brothers, both German communists living as refugees in America during World War II, in motivating the Committee to launch its first Hollywood probe. -

AMBASSADOR JOHN GUNTHER DEAN Interviewed By: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial Interview Date; September 6, 2000 Copyright 2000 ADST

AMBASSADOR JOHN GUNTHER DEAN Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial Interview Date; September 6, 2000 Copyright 2000 ADST Q. Today is September 6, 2000. This is an interview with John Gunther Dean. This is being done on behalf of the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training. I'm Charles Stuart Kennedy. Let's start at the beginning. Could you tell me when and where you were born and something about your family. DEAN: Okay. I was born on February 24, 1926 in the German city of Breslau, an industrial city of 650,000 people, where they made locomotives, airplanes. Silesia is one of the two lungs of Germany: the Ruhr Valley and Silesia. My father was a corporation lawyer who was on the Board of Directors of banks, chairman of a machine-tool company, mining corporations, etc... He was close to many of the leading industrial and financial people in Germany, in the period between the First World War and the Second World War. My father was also the President of the Jewish Community in Breslau. His friend Max Warburg played the same role in Hamburg. Q. Was this the banking Warburg. DEAN: That's right. Max Warburg was the head of the banking house at that time. Sigmund was his nephew who went to England. Q. "Dean" was ... DEAN: My father changed our name legally by going to court in New York Dean - 1 in March 1939. My father's name was Dr. Josef Dienstfertig. You will find his name in books listing the prominent men in industry and finance at the time. -

TOM MCINTOSH NEA Jazz Master (2008)

Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. TOM MCINTOSH NEA Jazz Master (2008) Interviewee: Tom McIntosh (December 6, 1927 – July 26, 2017) Interviewer: Eric Jackson with recording engineer Ken Kimery Date: December 9-10, 2011 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History Description: Transcript, 57 pp. Eric Jackson: Today is Friday December 9th. We are talking to Tom “Mac” McIntosh. Tom, let’s begin at the beginning. You were born in Baltimore December 6th 1927? McIntosh: Baltimore, Maryland. Eric Jackson: Baltimore, Maryland. December 6th, 1927? McIntosh: That is correct. Eric Jackson: How big was your family? Were you the youngest, the oldest…? McIntosh: My father had a son by another woman that was seven years older than me. I was the oldest of my mother’s children. My mother had six children. I was the oldest of the six. Eric Jackson: Was it a musical household? McIntosh: Fortunately, I had a mother and a father that were musically inclined. My father, he yearned to be the lead singer in the Mills Brothers. I didn’t appreciate that until later on in years when I discovered that Dean Martin and Frank Sinatra all said that it was the leader of the Mills Brothers that made them want to sing. And looking back, my father was like the leader had a paunch on. But, he made it attractive For additional information contact the Archives Center at 202.633.3270 or [email protected] because he could move his belly in sync with the rhythm of “the lazy river…” (Scats the song) And his belly is moving in rhythm with it! He was always very attractive. -

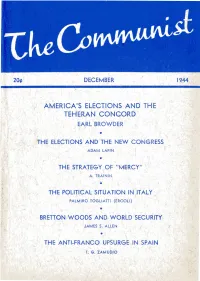

The Communist a Marxist Magazine Devoted to Advancement of Democratic Thought and Action

DECEMBER 1944 ,' AMERICA•s ELECTIONS AND THE TEHERAN CONCORD EA RL BROWDER ' I • THE ELECTipNS AND THE NEW CONGRESS ADAM LAPIN t ' r • THE STRATEGY OF "MERCY " A. TRAININ • THE POLITICA L SITUATION IN ITALY ( . PALMIRO TOGLIATTI (ERCOLI) • BRETTON WOODS AND WORLD SECURITY JAMES S. ALLEN • THE A NTI-FRA NCO U PS URG~ IN SPAIN T. G. ZAMUDIO Just Published- MORALE EDUCATION IN THE AMERICAN ARMY BY PHILIP FONER In this new study, a distinguished American historian brings to light a wealth of material, including documents and speeches by Washington, Jackson and Lincoln, letters from soldiers, contemporary newspaper articles and editorials, .)'esolutions and activities of workers' and other patriotic organi,2ations backing up the fighting fronts, all skiijfully woven together to make an illuminating analysis of the role of morale in the three great wars of American history-the War of Independence, the War of 1812, and the Civil War. Price 20¢ MARX AND ENGELS ON REACTION ARY PRUSSIANIS·M ~ An important theoretical study which assembles the writings and opinions of Marx and Engels on the histori~ roots, .charaCter and reafclonary political and military role of the Prussian Junkers, and illuminates the background of the plans for world domination hatched by the Ge;man general staH, the modern industrialists_and the criminal Nazi clique. Prle..e iO¢ WALT WHIT MAN- POET OF AMERICAN DEMOCRACY BY SAMUEL SILLEN A new study of the great American poet, together with a discerning selec- - tion from his prose and poetic writings which throws light on Whitman's views on the Civil War, democracy, labor, internationalism, culture, etc. -

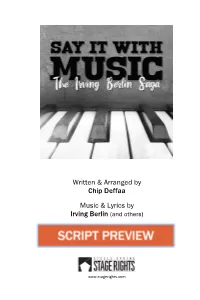

See Script Preview

Written & Arranged by Chip Deffaa Music & Lyrics by Irving Berlin (and others) PRODUCTION SCRIPT www.stagerights.com SAY IT WITH MUSIC: THE IRVING BERLIN SAGA Copyright © 2018 by Chip Deffaa All Rights Reserved All performances and public readings of SAY IT WITH MUSIC: THE IRVING BERLIN SAGA are subject to royalties. It is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America, of all countries covered by the International Copyright Union, of all countries covered by the Pan-American Copyright Convention and the Universal Copyright Convention, and all countries with which the United States has reciprocal copyright relations. All rights are strictly reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, by any means, including mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the author. Publication of this play does not necessarily imply that it is available for performance by amateurs or professionals. It is strongly recommended all interested parties apply to Steele Spring Stage Rights for performance rights before starting rehearsals or advertising. No changes shall be made in the play for the purpose of your production without prior written consent. All billing stipulations in your license agreement must be strictly adhered to. No person, firm or entity may receive credit larger or more prominent than that accorded the Author. For all stage performance inquiries, please contact: Steele Spring Stage Rights 3845 Cazador Street Los Angeles, CA 90065 (323) 739-0413 www.stagerights.com PRODUCTION HISTORY The first reading of this musical play, under the direction of playwright Chip Deffaa, took place on February 19, 2018 at New York’s 13th Street Repertory Theater (Edith O’Hara, founder/original artistic director; Joe Battista, managing director), starring Michael Townsend Wright, Suzanne Dressler, and Jed Q. -

The Political History of Classical Hollywood: Moguls, Liberals and Radicals in The

The political history of Classical Hollywood: moguls, liberals and radicals in the 1930s Professor Mark Wheeler, London Metropolitan University Introduction Hollywood’s relationship with the political elite in the Depression reflected the trends which defined the USA’s affairs in the interwar years. For the moguls mixing with the powerful indicated their acceptance by America’s elites who had scorned them as vulgar hucksters due to their Jewish and show business backgrounds. They could achieve social recognition by demonstrating a commitment to conservative principles and supported the Republican Party. However, MGM’s Louis B. Mayer held deep right-wing convictions and became the vice-chairman of the Southern Californian Republican Party. He formed alliances with President Herbert Hoover and the right-wing press magnate William Randolph Hearst. Along with Hearst, Will Hays and an array of Californian business forces, ‘Louie Be’ and MGM’s Production Chief Irving Thalberg led a propaganda campaign against Upton Sinclair’s End Poverty in California (EPIC) gubernatorial election crusade in 1934. This form of ‘mogul politics’ was characterized by the instincts of its authors: hardness, shrewdness, autocracy and coercion. 1 In response to the mogul’s mercurial values, the Hollywood community pursued a significant degree of liberal and populist political activism, along with a growing radicalism among writers, directors and stars. For instance, James Cagney and Charlie Chaplin supported Sinclair’s EPIC campaign by attending meetings and collecting monies. Their actions reflected the economic, social and political conditions of the era, notably the collapse of US capitalism with the Great Depression, the New Deal, the establishment of trade unions, and the emigration of European political refugees due to Nazism.