A Cache of Mesquite Beans from the Mecca Hills, Salton Basin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VGP) Version 2/5/2009

Vessel General Permit (VGP) Version 2/5/2009 United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) VESSEL GENERAL PERMIT FOR DISCHARGES INCIDENTAL TO THE NORMAL OPERATION OF VESSELS (VGP) AUTHORIZATION TO DISCHARGE UNDER THE NATIONAL POLLUTANT DISCHARGE ELIMINATION SYSTEM In compliance with the provisions of the Clean Water Act (CWA), as amended (33 U.S.C. 1251 et seq.), any owner or operator of a vessel being operated in a capacity as a means of transportation who: • Is eligible for permit coverage under Part 1.2; • If required by Part 1.5.1, submits a complete and accurate Notice of Intent (NOI) is authorized to discharge in accordance with the requirements of this permit. General effluent limits for all eligible vessels are given in Part 2. Further vessel class or type specific requirements are given in Part 5 for select vessels and apply in addition to any general effluent limits in Part 2. Specific requirements that apply in individual States and Indian Country Lands are found in Part 6. Definitions of permit-specific terms used in this permit are provided in Appendix A. This permit becomes effective on December 19, 2008 for all jurisdictions except Alaska and Hawaii. This permit and the authorization to discharge expire at midnight, December 19, 2013 i Vessel General Permit (VGP) Version 2/5/2009 Signed and issued this 18th day of December, 2008 William K. Honker, Acting Director Robert W. Varney, Water Quality Protection Division, EPA Region Regional Administrator, EPA Region 1 6 Signed and issued this 18th day of December, 2008 Signed and issued this 18th day of December, Barbara A. -

4 Riverside County Ranges Guide No

4 RIVERSIDE COUNTY RANGES GUIDE NO. 4.6 OROCOPIA MOUNTAIN 3815 FEET CLASS 1 MILEAGE: 156 miles of paved road, 3.8 miles of good dirt, 0.4 miles of 4WD road DRIVE/ROUTE A: See Map 1. From Indio, CA. drive 23 miles E on Interstate 10 to the signed Mecca- Twentynine Palms exit. Turn right (S) and drive 0.35 miles to the paved, signed Pinto Road. Turn left (E) here and go 0.6 miles to a good dirt road heading S. Turn right (S), crossing under high voltage power lines in 0.95 miles and bearing left at the fork just past the power lines (MC 133). Continue 2.85 miles S to a junction, bearing left at all forks encountered along the way. Further progress is barred by a rock barrier across the sand wash road directly S of this junction. 2WD's park here. 4WD's can continue by taking a sharp left up a steep hill and going 75 yards to a fork. Bear right (S) at the fork and drive 0.4 miles to the Orocopia Mountains Wilderness boundary. Park. CLIMB/ROUTE A: See Map 1. From the 4WD parking area, walk 0.3 miles up the road to where it passes through a deep, narrow gully. Once across the gully, hike 0.5 miles S along the left bank of a large wash. Dropping into the wash here, follow it S for about 0.75 miles until you reach a fork with a large wash merging from the right (W) at UTM 133157. -

The California Desert CONSERVATION AREA PLAN 1980 As Amended

the California Desert CONSERVATION AREA PLAN 1980 as amended U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management Desert District Riverside, California the California Desert CONSERVATION AREA PLAN 1980 as Amended IN REPLY REFER TO United States Department of the Interior BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT STATE OFFICE Federal Office Building 2800 Cottage Way Sacramento, California 95825 Dear Reader: Thank you.You and many other interested citizens like you have made this California Desert Conservation Area Plan. It was conceived of your interests and concerns, born into law through your elected representatives, molded by your direct personal involvement, matured and refined through public conflict, interaction, and compromise, and completed as a result of your review, comment and advice. It is a good plan. You have reason to be proud. Perhaps, as individuals, we may say, “This is not exactly the plan I would like,” but together we can say, “This is a plan we can agree on, it is fair, and it is possible.” This is the most important part of all, because this Plan is only a beginning. A plan is a piece of paper-what counts is what happens on the ground. The California Desert Plan encompasses a tremendous area and many different resources and uses. The decisions in the Plan are major and important, but they are only general guides to site—specific actions. The job ahead of us now involves three tasks: —Site-specific plans, such as grazing allotment management plans or vehicle route designation; —On-the-ground actions, such as granting mineral leases, developing water sources for wildlife, building fences for livestock pastures or for protecting petroglyphs; and —Keeping people informed of and involved in putting the Plan to work on the ground, and in changing the Plan to meet future needs. -

Desert Bighorn Sheep Report

California Department of Fish and Wildlife Region 6 Desert Bighorn Sheep Status Report November 2013 to October 2016 A summary of desert bighorn sheep population monitoring and management by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife Authors: Paige Prentice, Ashley Evans, Danielle Glass, Richard Ianniello, and Tom Stephenson Inland Deserts Region California Department of Fish and Wildlife Desert Bighorn Status Report 2013-2016 California Department of Fish and Wildlife Inland Deserts Region 787 N. Main Street Ste. 220 Bishop, CA 93514 www.wildlife.ca.gov This document was finalized on September 6, 2018 Page 2 of 40 California Department of Fish and Wildlife Desert Bighorn Status Report 2013-2016 Table of Contents Executive Summary …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………4 I. Monitoring ............................................................................................................................................ 6 A. Data Collection Methods .................................................................................................................. 7 1. Capture Methods .......................................................................................................................... 7 2. Survey Methods ............................................................................................................................ 8 B. Results and Discussion .................................................................................................................... 10 1. Capture Data .............................................................................................................................. -

PDF Linkchapter

Index (Italic page numbers indicate major references) Abalone Cove landslide, California, Badger Spring, Nevada, 92, 94 Black Dyke Formation, Nevada, 69, 179, 180, 181, 183 Badwater turtleback, California, 128, 70, 71 abatement districts, California, 180 132 Black Mountain Basalt, California, Abrigo Limestone, Arizona, 34 Bailey ash, California, 221, 223 135 Acropora, 7 Baked Mountain, Alaska, 430 Black Mountains, California, 121, Adams Argillite, Alaska, 459, 462 Baker’s Beach, California, 267, 268 122, 127, 128, 129 Adobe Range, Nevada, 91 Bald Peter, Oregon, 311 Black Point, California, 165 Adobe Valley, California, 163 Balloon thrust fault, Nevada, 71, 72 Black Prince Limestone, Arizona, 33 Airport Lake, California, 143 Banning fault, California, 191 Black Rapids Glacier, Alaska, 451, Alabama Hills, California, 152, 154 Barrett Canyon, California, 202 454, 455 Alaska Range, Alaska, 442, 444, 445, Barrier, The, British Columbia, 403, Blackhawk Canyon, California, 109, 449, 451 405 111 Aldwell Formation, Washington, 380 Basin and Range Province, 29, 43, Blackhawk landslide, California, 109 algae 48, 51, 53, 73, 75, 77, 83, 121, Blackrock Point, Oregon, 295 Oahu, 6, 7, 8, 10 163 block slide, California, 201 Owens Lake, California, 150 Basin Range fault, California, 236 Blue Lake, Oregon, 329 Searles Valley, California, 142 Beacon Rock, Oregon, 324 Blue Mountains, Oregon, 318 Tatonduk River, Alaska, 459 Bear Meadow, Washington, 336 Blue Mountain unit, Washington, 380 Algodones dunes, California, 101 Bear Mountain fault zone, California, -

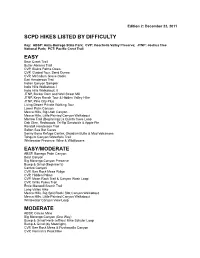

MASTER HIKE Filecomp

Edition 2: December 22, 2011 SCPD HIKES LISTED BY DIFFICULTY Key: ABSP: Anza-Borrego State Park; CVP: Coachella Valley Preserve; JTNP: Joshua Tree National Park; PCT: Pacific Crest Trail EASY Bear Creek Trail Butler-Abrams Trail CVP, Biskra Palms Oasis CVP, Guided Tour, Sand Dunes CVP, McCallum Grove Oasis Earl Henderson Trail Indian Canyon Sampler Indio Hills Walkabout, I Indio Hills Walkabout, II JTNP, Barker Dam and Wall Street Mill JTNP, Keys Ranch Tour & Hidden Valley Hike JTNP, Pine City Plus Living Desert Private Walking Tour Lower Palm Canyon Mecca Hills, Big Utah Canyon Mecca Hills, Little Painted Canyon Walkabout Morrow Trail (Beginning) La Quinta Cove Loop Oak Glen, Redwoods, Tri-Tip Sandwich & Apple Pie Randall Henderson Trail Salton Sea Bat Caves Sonny Bono Refuge Center, Obsidian Butte & Mud Volcanoes Tahquitz Canyon Waterfalls Trail Whitewater Preserve: Wine & Wildflowers EASY/MODERATE ABSP, Borrego Palm Canyon Bear Canyon Big Morongo Canyon Preserve Bump & Grind (Beginner’s) Carrizo Canyon CVP, Bee Rock Mesa Ridge CVP, Hidden Palms CVP, Moon Rock Trail & Canyon Wash Loop CVP, Willis Palms Trail Ernie Maxwell Scenic Trail Long Valley Hike Mecca Hills, Big Split Rock/ Slot Canyon Walkabout Mecca Hills, Little Painted Canyon Walkabout Whitewater Canyon View Loop MODERATE ABSP, Calcite Mine Big Morongo Canyon (One Way) Bump & Grind/ Herb Jeffries/ Mike Schuler Loop Bump & Grind (by Moonlight) CVP, Bee Rock Mesa & Pushawalla Canyon CVP, Herman’s Peak Hike CVP, Horseshoe Palms Hike CVP, Pushawalla Canyon Eisenhower Peak Loop, -

Section 3.11 Aesthetics Jan 11 02 SM Rev 4

3.11 Aesthetics 3.11.1 Introduction and Summary This section presents the environmental setting and impacts related to aesthetic resources in the four geographic subregions. The aesthetic characteristics of an area are determined by the manner in which the resources contained in that area are perceived. Baseline aesthetic conditions are primarily described in terms of existing visual resources. Aesthetics discussions related to the Salton Sea also include a description of the olfactory character (odors) of that specific geographic subregion, which are briefly described below. Visual resources along the LCR include volcanic mountain ranges and hills; distinctive sand dunes; broad areas of the Joshua tree, alkali scrub, and cholla communities; and elevated river terraces (California Department of Water Resources [DWR] 1994). Views of the LCR occur at various locations along I-95. The IID water service area is characterized visually by substantial agricultural production and associated heavy machinery. Beyond the IID water service area, deserts, sand dunes, mountains, and the Salton Sea characterize the visual resources. Visual resources in the area of the Salton Sea geographic subregion include various landforms, vegetation, man-made structures, and the Sea itself. The Salton Sea covers approximately 211,000 acres (330 square miles) and is immediately surrounded by a sparsely vegetated desert landscape, which gives way to rocky, sandy hills (SSA and Reclamation 2000). The presence of odors at the Salton Sea currently affects both visitor numbers and resident populations in the area. Factors contributing to odors at the Salton Sea include water quality, high nutrient levels, and biological factors, such as fish and bird die-offs. -

ORWA26 750UTM: Oregon/Washington 750 Meter

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY ANALYTICAL RESULTS AND SAMPLE LOCALITY MAP FOR ROCK, STREAM-SEDIMENT, AND SOIL SAMPLES, NORTHERN AND EASTERN COLORADO DESERT BLM RESOURCE AREA, IMPERIAL, RIVERSIDE, AND SAN BERNARDINO COUNTIES, CALIFORNIA By H.D. King* and M.A. Chaffee* Open-File Report 00-105 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards or with the North American Stratigraphic Code. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. *U.S. Geological Survey, Denver Federal Center, Box 25046, MS 973, Denver, CO 80225-0046 2000 CONTENTS (blue text indicates a link) INTRODUCTION SAMPLE COLLECTION AND PREPARATION ANALYTICAL METHODS DESCRIPTION OF DATA TABLES OTHER INFORMATION ACKNOWLEDGMENTS REFERENCES CITED ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 1. Maps showing location of the Northern and Eastern Colorado Desert BLM Resource Area, California Figure 2. Site locality map for rock, stream-sediment, and soil samples from the Northern and Eastern Colorado Desert BLM Resource Area and vicinity TABLES Table 1. Lower limits of determination for ACTLABS instrumental neutron activation analysis (INAA) and inductively coupled plasma-atomic emission spectrometric analysis (ICP-AES) Table 2. Lower limits of determination for inductively coupled plasma-atomic emission spectrometry (ICP-AES) methods used by USGS and by XRAL Laboratories Table 3. Results for the analysis of 132 rock samples from the Northern and Eastern Colorado Desert BLM Resource Area Table 4. Results for the analysis of 284 USGS stream-sediment samples from the Northern and Eastern Colorado Desert BLM Resource Area Table 5. -

California Availability of Books and Maps of the U.S

CALIFORNIA AVAILABILITY OF BOOKS AND MAPS OF THE U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Instructions on ordering publications of the U.S. Geological Survey, along with prices of the last offerings, are given in the cur rent-year issues of the monthly catalog "New Publications of the U.S. Geological Survey." Prices of available U.S. Geological Sur vey publications released prior to the current year are listed in the most recent annual "Price and Availability List." Publications that are listed in various U.S. Geological Survey catalogs (see back inside cover) but not listed in the most recent annual "Price and Availability List" are no longer available. Prices of reports released to the open files are given in the listing "U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Reports," updated month ly, which is for sale in microfiche from the U.S. Geological Survey, Books and Open-File Reports Section, Federal Center, Box 25425, Denver, CO 80225. Reports released through the NTIS may be obtained by writing to the National Technical Information Service, U.S. Department of Commerce, Springfield, VA 22161; please include NTIS report number with inquiry. Order U.S. Geological Survey publications by mail or over the counter from the offices given below. BY MAIL Books OVER THE COUNTER Books Professional Papers, Bulletins, Water-Supply Papers, Techniques of Water-Resources Investigations, Circulars, publications of general in Books of the U.S. Geological Survey are available over the terest (such as leaflets, pamphlets, booklets), single copies of Earthquakes counter at the following Geological Survey Public Inquiries Offices, al~ & Volcanoes, Preliminary Determination of Epicenters, and some mis of which are authorized agents of the Superintendent of Documents: cellaneous reports, including some of the foregoing series that have gone out of print at the Superintendent of Documents, are obtainable by mail from • WASHINGTON, D.C.--Main Interior Bldg., 2600 corridor, 18th and C Sts., NW. -

California Desert Protection Act of 1993 CIS-NO

93 CIS S 31137 TITLE: California Desert Protection Act of 1993 CIS-NO: 93-S311-37 SOURCE: Committee on Energy and Natural Resources. Senate DOC-TYPE: Hearing DOC-NO: S. Hrg. 103-186 DATE: Apr. 27, 28, 1993 LENGTH: iii+266 p. CONG-SESS: 103-1 ITEM-NO: 1040-A; 1040-B SUDOC: Y4.EN2:S.HRG.103-186 MC-ENTRY-NO: 94-3600 INCLUDED IN LEGISLATIVE HISTORY OF: P.L. 103-433 SUMMARY: Hearings before the Subcom on Public Lands, National Parks, and Forests to consider S. 21 (text, p. 4-92), the California Desert Protection Act of 1993, to: a. Expand or designate 79 wilderness areas, one wilderness study area in the California Desert Conservation Area, and one natural reserve. b. Expand and redesignate the Death Valley National Monument as the Death Valley National Park and the Joshua Tree National Monument as the Joshua Tree National Park. c. Establish the Mojave National Park and the Desert Lily Sanctuary. d. Direct the Department of Interior to enter into negotiations with the Catellus Development Corp., a publicly owned real estate development corporation, for an agreement or agreements to exchange public lands or interests for Catellus lands or interests which are located within the boundaries of designated wilderness areas or park units. e. Withdraw from application of public land laws and reserve for Department of Navy use certain Federal lands in the California desert. f. Permit military aircraft training and testing overflights of the wilderness areas and national parks established in the legislation. Title VIII is cited as the California Military Lands Withdrawal and Overflights Act of 1991. -

U.S. Geological Survey Final Technical Report Award No

U.S. Geological Survey Final Technical Report Award No. G12AP20066 Recipient: University of California at Santa Barbara Mapping the 3D Geometry of Active Faults in Southern California Craig Nicholson1, Andreas Plesch2, John Shaw2 & Egill Hauksson3 1Marine Science Institute, UC Santa Barbara 2Department of Earth & Planetary Sciences, Harvard University 3Seismological Laboratory, California Institute of Technology Principal Investigator: Craig Nicholson Marine Science Institute, University of California MC 6150, Santa Barbara, CA 93106-6150 phone: 805-893-8384; fax: 805-893-8062; email: [email protected] 01 April 2012 - 31 March 2013 Research supported by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), Department of the Interior, under USGS Award No. G12AP20066. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors, and should not be interpreted as necessarily representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the U.S. Government. 1 Mapping the 3D Geometry of Active Faults in Southern California Abstract Accurate assessment of the seismic hazard in southern California requires an accurate and complete description of the active faults in three dimensions. Dynamic rupture behavior, realistic rupture scenarios, fault segmentation, and the accurate prediction of fault interactions and strong ground motion all strongly depend on the location, sense of slip, and 3D geometry of these active fault surfaces. Comprehensive and improved catalogs of relocated earthquakes for southern California are now available for detailed analysis. These catalogs comprise over 500,000 revised earthquake hypocenters, and nearly 200,000 well-determined earthquake focal mechanisms since 1981. These extensive catalogs need to be carefully examined and analyzed, not only for the accuracy and resolution of the earthquake hypocenters, but also for kinematic consistency of the spatial pattern of fault slip and the orientation of 3D fault surfaces at seismogenic depths. -

USGS DDS-43, Recreation in the Sierra

TIMOTHY P. DUANE Department of City and Regional Planning and Department of Landscape Architecture University of California 19 Berkeley, California Recreation in the Sierra ABSTRACT Recreation is a significant activity in the Sierra Nevada, which serves INTRODUCTION as a center for a wide range of recreational activities. The Sierra con- The Sierra Nevada region is a popular destination for tains some of the world’s outstanding natural features, and they at- recreationists. Year-round local residents and California resi- tract visitors from throughout the country and the world. Lake Tahoe, dents and nonresidents pursue a wide variety of recreational Yosemite Valley, Mono Lake, and the Sequoia Big Trees attract mil- activities. These pursuits occur throughout the entire region, lions of visitors each year. Recreational activities on public lands alone from the bottom of steep river canyons to the top of the high- account for between 50 and 60 million recreational visitor days (RVDs) est mountain peaks. The mountain range is the natural infra- per year, with nearly three-fifths to two-thirds of those RVDs occur- structure that supports wilderness backpackers, skiers, fishing ring on lands administered by the U.S. Forest Service. The Califor- enthusiasts, off-road vehicle users, naturalists, and many oth- nia Department of Parks and Recreation has the second greatest ers. All individuals who pursue outdoor activities within the number of RVDs, followed by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, the Sierra Nevada rely upon the natural world for an enjoyable National Park Service, and the U.S. Bureau of Land Management. experience. The ecological conditions of the Sierra Nevada Additional recreational activities on private lands account for millions are therefore important factors influencing patterns of recre- more RVDs that are currently not accounted for by any agency in a ational activity.