ESID Working Paper No. 129 Managing Coercion and Striving For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEIGHBOUR Against Dictatorship

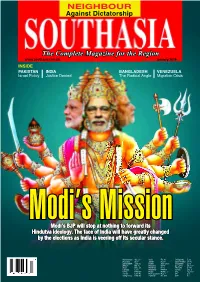

NEIGHBOUR Against Dictatorship www.southasia.com.pk January 2019 INSIDE PAKISTAN INDIA BANGLADESH VENEZUELA Israel Policy Justice Denied The Radical Angle Migration Crisis Modi’s Mission Modi’s BJP will stop at nothing to forward its Hindutva ideology. The face of India will have greatly changed by the elections as India is veering off its secular stance. Contents 14 The Name Changing Spree India wants to be a future Hindu state. Islamabad Kabul Batting For A Solution It seems new peace moves 39 concerning Afghanistan are bearing fruit. 31The Struggle Continues Women in Pakistan want more rights. Malé Towards a New Agenda 41 Solih too has a 100-day 36 agenda. New Delhi Arms Race Fever India aims to be the arms leader in South Asia. 4 SOUTHASIA • JANUARY 2019 REGULAR FEATURES Editor’s Mail 8 On Record 9 Briefs 10 COVER STORY The Name Changing Spree 14 Directionless Development 15 In The Name of Ram 17 More to the Mania 18 No Walkover 20 End of Secularism 21 Towards the Ram Mandir 23 The Contest 24 Interview: Lt. Gen. Zameer Uddin Shah 25 REGION Islamabad 44 Future of SAARC 30 International Islamabad A Growing Crisis The Struggle Continues 31 Key problems are rocking Venezuela. Islamabad Revisiting No-No Land 32 Islamabad Recovering The Money 34 Gwadar The Gender Front 35 New Delhi Arms Race Fever 36 Kabul & Islamabad Harbingers of Peace 38 49 Kabul Neighbour Batting For A Solution 39 Church Split Malé Christianity faces a crisis of its own. Towards a New Agenda 41 INTERNATIONAL A Growing Crisis 44 Trade Winds 45 NEIGHBOUR Defiant Rap 48 Church Split 49 Storm in the Gulf 51 57 FEATURES Chittagong Islamabad The Radical Angle A Dark Day 54 Radical groups are New Delhi coming together in Crisis of Cleanliness 55 Bangladesh. -

ESID Working Paper No. 132 the 2018 Bangladeshi Election

ESID Working Paper No. 132 The 2018 Bangladeshi election Mathilde Maitrot1 David Jackman2 January 2020 1 University of Bath Email correspondence: [email protected] 2 University of Oxford Email correspondence: [email protected] ISBN: 978-1-912593-42-2 email: [email protected] Effective States and Inclusive Development Research Centre (ESID) Global Development Institute, School of Environment, Education and Development, The University of Manchester, Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9PL, UK www.effective-states.org The 2018 Bangladeshi election Abstract Between 1990 and 2009, the violent competition characteristic of Bangladeshi politics was tempered during elections through a system of caretaker government, which managed successfully to adjudicate between parties in a neutral manner. Since the system was repealed in 2011 however, elections have more closely resembled those seen previously under military rule. This paper examines the most recent election, the controversial 2018 landslide victory for the Awami League. Based on a multi-site analysis, we examine how the victory was achieved, reviewing the candidate nomination process, campaigns and election day itself. The ruling party’s success lies in efficient party management, with factionalism kept in check, an appealing vision of a developed and ‘digital’ Bangladesh and, most fundamentally, widespread coercion of political opposition using the apparatus of the state. The election articulates two key characteristics of contemporary Bangladeshi politics: state coercion and developmentalist ambitions. Keywords: Bangladesh, elections, coercion, security agencies, development, candidates Maitrot, M. and Jackman, D. (2020) The 2018 Bangladeshi election. ESID Working Paper No. 132. Manchester, UK: The University of Manchester. Available at www.effective-states.org This document is an output from a project funded by UK Aid from the UK government for the benefit of developing countries. -

NO PLACE for CRITICISM Bangladesh Crackdown on Social Media Commentary WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS NO PLACE FOR CRITICISM Bangladesh Crackdown on Social Media Commentary WATCH No Place for Criticism Bangladesh Crackdown on Social Media Commentary Copyright © 2018 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-36017 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org MAY 2018 ISBN: 978-1-6231-36017 No Place for Criticism Bangladesh Crackdown on Social Media Commentary Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Information and Communication Act ......................................................................................... 3 Punishing Government Critics ...................................................................................................4 Protecting Religious -

Caught Between Fear and Repression

CAUGHT BETWEEN FEAR AND REPRESSION ATTACKS ON FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION IN BANGLADESH Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2017 Cover design and illustration: © Colin Foo Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2017 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street, London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: ASA 13/6114/2017 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION TIMELINE 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY & METHODOLOGY 6 1. ACTIVISTS LIVING IN FEAR WITHOUT PROTECTION 13 2. A MEDIA UNDER SIEGE 27 3. BANGLADESH’S OBLIGATIONS UNDER INTERNATIONAL LAW 42 4. BANGLADESH’S LEGAL FRAMEWORK 44 5. CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS 57 Glossary AQIS - al-Qa’ida in the Indian Subcontinent -

2012-0164-En-Ap

Hotline Newsletter (Bi-monthly Newsletter) 177th Issue Feb.-Mar. 2012 Editorial RAB needs Human Rights Training Bangladesh has been going through a trauma of extra- The six so-called muggers killed in Narsingdi by Rab judicial killings by the elite force members of RAB since raised serious questions. Challenging Rab’s version, the 2004. It was started during the BNP-Jamaat four-party victims’ relatives maintained that none of the victims were alliance. The purpose of this newly formed elite force muggers. Whatever the truth, the very method of Rab’s was to eradicate the country from all terrors and muggers. killing is simply unacceptable because it is against the Up to now this elite force has killed over two thousand norms of civilized law and harks back to the days when people, of whom most are claimed to be innocent by their the law of the jungle prevailed. Even if they were real relatives. During that time the present party in power, muggers, why would they be killed at all? As per the the, Awami League was in the opposition and they were constitution and the UN Declaration of Human Rights very much against such extra-judicial killings. Awami everyone has the right to life. Under what legal authority League was also against the corruption of BNP-Jamaat are suspected ‘criminals’ or ‘muggers’, on a tip-off from and their mismanagement of power and money. an unidentified businessman, such such a murderous Today corruption has become a way of life for the assault be perpetrated in broad daylight by law enforcers? citizens of Bangladesh, irrespective of their socio- In the meantime, the law enforcers failed to find out the economic background. -

BANGLADESH: from AUTOCRACY to DEMOCRACY (A Study of the Transition of Political Norms and Values)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by KDI School Archives BANGLADESH: FROM AUTOCRACY TO DEMOCRACY (A Study of the Transition of Political Norms and Values) By Golam Shafiuddin THESIS Submitted to School of Public Policy and Global Management, KDI in partial fulfillment of the requirements the degree of MASTER OF PUBLIC POLICY 2002 BANGLADESH: FROM AUTOCRACY TO DEMOCRACY (A Study of the Transition of Political Norms and Values) By Golam Shafiuddin THESIS Submitted to School of Public Policy and Global Management, KDI in partial fulfillment of the requirements the degree of MASTER OF PUBLIC POLICY 2002 Professor PARK, Hun-Joo (David) ABSTRACT BANGLADESH: FROM AUTOCRACY TO DEMOCRACY By Golam Shafiuddin The political history of independent Bangladesh is the history of authoritarianism, argument of force, seizure of power, rigged elections, and legitimacy crisis. It is also a history of sustained campaigns for democracy that claimed hundreds of lives. Extremely repressive measures taken by the authoritarian rulers could seldom suppress, or even weaken, the movement for the restoration of constitutionalism. At times the means adopted by the rulers to split the opposition, create a democratic facade, and confuse the people seemingly served the rulers’ purpose. But these definitely caused disenchantment among the politically conscious people and strengthened their commitment to resistance. The main problems of Bangladesh are now the lack of national consensus, violence in the politics, hartal (strike) culture, crimes sponsored with political ends etc. which contribute to the negation of democracy. Besides, abject poverty and illiteracy also does not make it easy for the democracy to flourish. -

By Mohammed Syful Islam on “Koun Bonega Crorepati

By Mohammed Syful Islam On “Koun Bonega Crorepati” (“Who Will Be The Owner of Crore of Taka”), a popular game show on India’s Zee TV, participants answer general knowledge questions to win one crore taka [one crore is equal to 10 million taka (US$145,571). But Bangladeshi politicians-regardless of name or seniority-do not need a TV game show to quickly earn several crores of taka. Thanks to a recent anti-corruption drive by the interim government that has revealed hundreds of cases of corruption, the Bangladeshi people now know that politicians and government officials have deceived them and earned crores of taka by abusing power. Public opinion surveys from 2001 through 2006 show that people perceive Bangladesh as one of the most corrupt countries in the world, much to the denial of political leaders. “Under the political governments of two ladies-Sheikh Hasina and Begum Khaleda Zia-corruption was made a way of life at all levels, particularly at the corridors of power,” says Golam Haider, a senior journalist at The New Nation newspaper . “It was openly patronized and practiced across the table. Despite the interim government’s anti-corruption efforts, corruption still exists; now it’s happening under the table. The anti-corruption drive is not running on the right track. Corrupt people cannot fight corruption, Haider says. Jasmin Rahman, a master’s student at a government university, says corruption begins at the school level. “A student who fails in school-level examinations still becomes eligible to sit for examinations under the education board, after she or he or their parents pay some bribe to the school authorities in the name of donation,” Rahman says. -

The Torture of Tasneem Khalil How the Bangladesh Military Abuses Its Power Under the State of Emergency

February 2008 Volume 20, No. 1 (C) The Torture of Tasneem Khalil How the Bangladesh Military Abuses Its Power under the State of Emergency I. Summary............................................................................................................... 1 II. Torture in Bangladesh..........................................................................................2 III. Assaults on Media Freedom ................................................................................7 IV. A Midnight Arrest, 22 Hours of Torture: The Case of Tasneem Khalil..................10 V. Tasneem’s Experience in the Context of the State of Emergency ........................37 VI. Recommendations ............................................................................................40 General issues ..................................................................................................40 Arrest and detention .........................................................................................40 Legal reforms .................................................................................................... 41 The international community............................................................................. 41 Acknowledgements................................................................................................43 I. Summary This report presents the testimony of Tasneem Khalil, recounting his torture at the hands of Bangladesh’s military intelligence agency, the Directorate General of Forces Intelligence (DGFI). -

FM Forts of Various State Agencies

BUSINESS | Page 1 SPORT | Page 1 El Arabi puts Duhail on top, INDEX DOW JONES QE NYMEX QATAR 2-8, 24 COMMENT 22, 23 Ooredoo to showcase Gharafa REGION 9 BUSINESS 1-14, 20-24 25,177.00 9,106.77 62.50 ARAB WORLD 9 CLASSIFIED 15-19 tech solutions at the -59.00 +27.34 +0.82 INTERNATIONAL 10-21 SPORTS 1-7 also win -0.23% +0.30% +1.33% Mobile World Congress Latest Figures published in QATAR since 1978 TUESDAY Vol. XXXVIII No. 10735 February 20, 2018 Jumada II 4, 1439 AH GULF TIMES www. gulf-times.com 2 Riyals Emir gets Sudanese president’s message Road deaths In brief and injuries QATAR | Reaction Church shooting in Russia condemned Qatar strongly condemned the fall in Qatar shooting that targeted a church in Russia’s southern province of oad deaths and injuries in Qatar arrival time at accident spots from 15 Dagestan, which caused a number declined in 2017 compared to minutes to around 5-7 minutes. The of deaths and injuries. In a statement R2016, the General Directorate of new driving test strategy and curricu- yesterday, Qatar’s Ministry of Foreign Traffi c announced yesterday. lum focuses on producing high quality Aff airs reiterated Qatar’s firm position “Only 5.4 road traffi c accident (RTA) drivers, equipped with proper traffi c rejecting violence and terrorism deaths per 100,000 persons were re- awareness. regardless of motives and reasons. It corded in the country last year, com- The use of more speed radars and expressed Qatar’s condolences to the His Highness the Emir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani has received a written message from Sudanese President Omar Hassan pared to the world average of 17.4,” surveillance cameras across greater families of the victims, the government al-Bashir, pertaining to the bilateral relations and ways to enhance them. -

Mapping Bangladesh's Political Crisis

Mapping Bangladesh’s Political Crisis Asia Report N°264 | 9 February 2015 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Anatomy of a Conflict ....................................................................................................... 3 A. A Bitter History .......................................................................................................... 3 B. Democracy Returns ................................................................................................... 5 C. The Caretaker Model Ends ........................................................................................ 5 D. The 2014 Election ...................................................................................................... 6 III. Political Dysfunction ........................................................................................................ 8 A. Parliamentary Incapacity ........................................................................................... 8 B. An Opposition in Disarray ......................................................................................... 9 1. BNP Politics ......................................................................................................... -

Mig-29 Corruption Trials – Awami League – Judiciary – Corruption

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: BGD34408 Country: Bangladesh Date: 23 March 2009 Keywords: Bangladesh – Caretaker Government – MiG-29 Corruption Trials – Awami League – Judiciary – Corruption This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Please provide key dates in the Bangladeshi government’s MiG-29 jet fighter aircraft purchase and later corruption trials. 2. Please provide information regarding the current status of any legal action, in particular against former Ministry of Defence officials such as Syed Yusuf Hossain and Hossain Serniabat. Please provide information confirming that the charges against President Sheikh Hasina have lapsed or have been formally dropped. 3. Do reports confirm that charges against Brigadier General (retired) Iftekhar-Ul-Bashar and former Ministry of Defence Deputy Secretary Hasan Mahmood Delwar were dropped for lack of evidence? 4. Please provide any other relevant information, for example the profile of the MiG-29 corruption case or public comment -

Global Corruption Report 2008 (Transparency International, 2008)

More than 1 billion people live with inadequate access to safe drinking water, with dramatic consequences for lives, livelihoods and development. Transparency International’s Global Corruption Report 2008 demonstrates in its thematic section that corruption is a cause and cat- alyst for this water crisis, which is likely to be further exacerbated by climate change. Corruption affects all aspects of the water sector, from water resources management to drink- ing water services, irrigation and hydropower. In this timely report, scholars and profession- als document the impact of corruption in the sector, with case studies from all around the world offering practical suggestions for reform. The second part of the Global Corruption Report 2008 provides a snapshot of corruption-related developments in thirty-five countries from all world regions. The third part presents sum- maries of corruption-related research, highlighting innovative methodologies and new empir- ical findings that help our understanding of the dynamics of corruption and in devising more effective anti-corruption strategies. Transparency International (TI) is the civil society organisation leading the global fight against corruption. Through more than ninety chapters worldwide and an international secretariat in Berlin, Germany, TI raises awareness of the damaging effects of corruption, and works with partners in government, business and civil society to develop and implement effective meas- ures to tackle it. For more information, go to www.transparency.org. Global Corruption Report 2008 Corruption in the Water Sector TRANSPARENCY INTERNATIONAL the global coalition against corruption CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo, Delhi Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 8RU, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521727952 © Transparency International 2008 This publication is in copyright.