ESID Working Paper No. 132 the 2018 Bangladeshi Election

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bangladesh Legislative Elections, 29 December 2008

LEGISLATIVE ELECTIONS IN BANGLADESH ELECTION OBSERVATION DELEGATION 27 – 31 December 2008 REPORT BY MR Charles TANNOCK CHAIRMAN OF THE DELEGATION Report 2 Annexes 7 1 INTRODUCTION Following an invitation from the Bangladeshi authorities, the Conference of Presidents decided at its meeting on 23 October to authorise the sending of a delegation of the European Parliament to observe the legislative elections in Bangladesh, at that time scheduled for the 18 December. The Constitutive Meeting of the EP EOM was held in Strasbourg on the 19th November and M. Robert Evans (PSE,UK) was elected Chairman. However, the rescheduling of the Election date in Bangladesh to the 29th December made it, unfortunately, not possible for many of the Members initially appointed by their Political Groups to maintain their availability. A new constitutive meeting was therefore held on the 10th December, with M. Charles Tannock (EPP/ED, UK) elected Chairman of a 4-strong delegation; as is customary, these Members were appointed by the political groups in accordance with the rolling d'Hondt system (the list of participants is annexed to this report; the ALDE political group gave its seat to the N/I group). Taking into account this change of dates, the Conference of Presidents re-examined the situation at its meeting of the 17th December and confirmed its initial decision to send a parliamentary delegation. As is usual, the European Parliament's delegation was fully integrated into the European Union Election Observation Mission (EU EOM), which was led by Mr Alexander Graf LAMBSDORFF, MEP (ALDE, D). The EU EOM deployed 150 observers from 25 EU Member States plus Norway and Switzerland. -

Network Centrality Based Team Formation: a Case Study on T-20 Cricket

Applied Computing and Informatics (2017) xxx, xxx–xxx Saudi Computer Society, King Saud University Applied Computing and Informatics (http://computer.org.sa) www.ksu.edu.sa www.sciencedirect.com Network centrality based team formation: A case study on T-20 cricket Paramita Dey a, Maitreyee Ganguly a, Sarbani Roy b,* a Department of Information Technology, Government College of Engineering and Ceramic Technology, Kolkata 700010, India b Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Jadavpur University, Kolkata 700032, India Received 22 August 2016; revised 14 October 2016; accepted 18 November 2016 KEYWORDS Abstract This paper proposes and evaluates the novel utilization of small world network proper- Social Network Analysis ties for the formation of team of players with both best performances and best belongingness within (SNA); the team network. To verify this concept, this methodology is applied to T-20 cricket teams. The Centrality measures; players are treated as nodes of the network, whereas the number of interactions between team mem- T-20 cricket; bers is denoted as the edges between those nodes. All intra country networks form the cricket net- Small world network; work for this case study. Analysis of the networks depicts that T-20 cricket network inherits all Clustering coefficient characteristics of small world network. Making a quantitative measure for an individual perfor- mance in the team sports is important with respect to the fact that for team selection of an Inter- national match, from pool of best players, only eleven players can be selected for the team. The statistical record of each player considered as a traditional way of quantifying the performance of a player. -

Police Video Shows Slurring Tiger India to Get World's First

22 Friday, June 2, 2017 SPORTS Root leads England to victoryand an unbroken 143 successive balls from Liam Scoreboard for the third wicket with Plunkett to leave Bangladesh skipper Eoin Morgan (75 not 261 for four in the 45th over. Bangladesh out). Fast bowler Plunkett took Tamim Iqbal c Buttler b Plunkett 128 But worryingly for England, four wickets for 59 runs Soumya Sarkar c sub (Bairstow) b Stokes 28 bidding to win their first major from his maximum 10 overs. Imrul Kayes c Wood b Plunkett 19 International Cricket Council ODI England came into this Mushfiqur Rahim c Hales b Plunkett 79 trophy, paceman Chris Woakes tournament featuring the Shakib Al Hasan c Stokes b Ball 10 bowled just two overs before world’s top eight ODI sides Sabbir Rahman c Roy b Plunkett 24 London suffering a potentially tournament- having made huge strides in Mahmuduallah not out 6 oe Root’s career-best ending left side strain. white-ball cricket in the past unbeaten 133 saw And Jason Roy, a day after two years. Mosaddek Hossain not out 2 EnglandJ to an eight-wicket Morgan guaranteed his tournament But they had to work Total (6 wkts, 50 overs) 305 win over Bangladesh in the place, fell for just one -- his fifth hard in the field against a England opening match of the 2017 single figure score in his last six ODI Bangladesh side skittled out J. Roy c Mustafizur Rahman b Mashrafe Mortaza 1 Champions Trophy at the innings. for just 84 by Champions A. Hales c sub (Sunzamul Islam) b Sabbir Rehman 95 Oval on Thursday. -

Indo-Bangladesh Relations

ISSN 0971-9318 HIMALAYAN AND CENTRAL ASIAN STUDIES (JOURNAL OF HIMALAYAN RESEARCH AND CULTURAL FOUNDATION) NGO in Special Consultative Status with ECOSOC, United Nations Vol. 7 Nos.3-4 July - December 2003 BANGLADESH SPECIAL Regimes, Power Structure and Policies in Bangladesh Redwanur Rahman Indo-Bangladesh Relations Anand Kumar India-Bangladesh Bilateral Trade: Issues and Concerns Indra Nath Mukherji Rise of Religious Radicalism in Bangladesh Apratim Mukarji Hindu Religious Minority in Bangladesh Haridhan Goswami and Zobaida Nasreen Situation of Minorities in Bangladesh Ruchira Joshi Conflict and the 1997 Peace Accord of Chittagong Hill Tracts Binalakshmi Nepram Demographic Invasion from Bangladesh Bibhuti Bhusan Nandy India and Bangladesh: The Border Issues Sreeradha Datta Bangladesh-Pakistan Relations Smruti S. Pattanaik HIMALAYAN AND CENTRAL ASIAN STUDIES Editor : K. WARIKOO Assistant Editor : SHARAD K. SONI © Himalayan Research and Cultural Foundation, New Delhi. * All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without first seeking the written permission of the publisher or due acknowledgement. * The views expressed in this Journal are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the opinions or policies of the Himalayan Research and Cultural Foundation. SUBSCRIPTION IN INDIA Single Copy (Individual) : Rs. 200.00 Annual (Individual) : Rs. 400.00 Institutions : Rs. 500.00 & Libraries (Annual) OVERSEAS (AIRMAIL) Single Copy : US $ 15.00 UK £ 10.00 Annual (Individual) : US $ 30.00 UK £ 20.00 Institutions : US $ 50.00 & Libraries (Annual) UK £ 35.00 The publication of this journal (Vol.7, Nos.3-4, 2003) has been financially supported by the Indian Council of Historical Research. -

NEIGHBOUR Against Dictatorship

NEIGHBOUR Against Dictatorship www.southasia.com.pk January 2019 INSIDE PAKISTAN INDIA BANGLADESH VENEZUELA Israel Policy Justice Denied The Radical Angle Migration Crisis Modi’s Mission Modi’s BJP will stop at nothing to forward its Hindutva ideology. The face of India will have greatly changed by the elections as India is veering off its secular stance. Contents 14 The Name Changing Spree India wants to be a future Hindu state. Islamabad Kabul Batting For A Solution It seems new peace moves 39 concerning Afghanistan are bearing fruit. 31The Struggle Continues Women in Pakistan want more rights. Malé Towards a New Agenda 41 Solih too has a 100-day 36 agenda. New Delhi Arms Race Fever India aims to be the arms leader in South Asia. 4 SOUTHASIA • JANUARY 2019 REGULAR FEATURES Editor’s Mail 8 On Record 9 Briefs 10 COVER STORY The Name Changing Spree 14 Directionless Development 15 In The Name of Ram 17 More to the Mania 18 No Walkover 20 End of Secularism 21 Towards the Ram Mandir 23 The Contest 24 Interview: Lt. Gen. Zameer Uddin Shah 25 REGION Islamabad 44 Future of SAARC 30 International Islamabad A Growing Crisis The Struggle Continues 31 Key problems are rocking Venezuela. Islamabad Revisiting No-No Land 32 Islamabad Recovering The Money 34 Gwadar The Gender Front 35 New Delhi Arms Race Fever 36 Kabul & Islamabad Harbingers of Peace 38 49 Kabul Neighbour Batting For A Solution 39 Church Split Malé Christianity faces a crisis of its own. Towards a New Agenda 41 INTERNATIONAL A Growing Crisis 44 Trade Winds 45 NEIGHBOUR Defiant Rap 48 Church Split 49 Storm in the Gulf 51 57 FEATURES Chittagong Islamabad The Radical Angle A Dark Day 54 Radical groups are New Delhi coming together in Crisis of Cleanliness 55 Bangladesh. -

NO PLACE for CRITICISM Bangladesh Crackdown on Social Media Commentary WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS NO PLACE FOR CRITICISM Bangladesh Crackdown on Social Media Commentary WATCH No Place for Criticism Bangladesh Crackdown on Social Media Commentary Copyright © 2018 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-36017 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org MAY 2018 ISBN: 978-1-6231-36017 No Place for Criticism Bangladesh Crackdown on Social Media Commentary Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Information and Communication Act ......................................................................................... 3 Punishing Government Critics ...................................................................................................4 Protecting Religious -

Caught Between Fear and Repression

CAUGHT BETWEEN FEAR AND REPRESSION ATTACKS ON FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION IN BANGLADESH Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2017 Cover design and illustration: © Colin Foo Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2017 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street, London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: ASA 13/6114/2017 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION TIMELINE 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY & METHODOLOGY 6 1. ACTIVISTS LIVING IN FEAR WITHOUT PROTECTION 13 2. A MEDIA UNDER SIEGE 27 3. BANGLADESH’S OBLIGATIONS UNDER INTERNATIONAL LAW 42 4. BANGLADESH’S LEGAL FRAMEWORK 44 5. CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS 57 Glossary AQIS - al-Qa’ida in the Indian Subcontinent -

2012-0164-En-Ap

Hotline Newsletter (Bi-monthly Newsletter) 177th Issue Feb.-Mar. 2012 Editorial RAB needs Human Rights Training Bangladesh has been going through a trauma of extra- The six so-called muggers killed in Narsingdi by Rab judicial killings by the elite force members of RAB since raised serious questions. Challenging Rab’s version, the 2004. It was started during the BNP-Jamaat four-party victims’ relatives maintained that none of the victims were alliance. The purpose of this newly formed elite force muggers. Whatever the truth, the very method of Rab’s was to eradicate the country from all terrors and muggers. killing is simply unacceptable because it is against the Up to now this elite force has killed over two thousand norms of civilized law and harks back to the days when people, of whom most are claimed to be innocent by their the law of the jungle prevailed. Even if they were real relatives. During that time the present party in power, muggers, why would they be killed at all? As per the the, Awami League was in the opposition and they were constitution and the UN Declaration of Human Rights very much against such extra-judicial killings. Awami everyone has the right to life. Under what legal authority League was also against the corruption of BNP-Jamaat are suspected ‘criminals’ or ‘muggers’, on a tip-off from and their mismanagement of power and money. an unidentified businessman, such such a murderous Today corruption has become a way of life for the assault be perpetrated in broad daylight by law enforcers? citizens of Bangladesh, irrespective of their socio- In the meantime, the law enforcers failed to find out the economic background. -

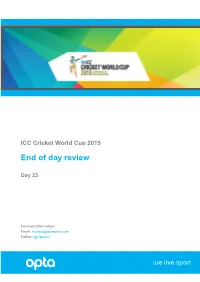

End of Day Review

ICC Cricket World Cup 2015 End of day review Day 23 For more information Email: [email protected] Twitter: @OptaJim Contents 1 Group Tables ......................................................................................................... 2 2 Fixtures/Results .................................................................................................... 2 3 Overall ODI team records ..................................................................................... 3 4 Squad event averages .......................................................................................... 4 5 Tournament player statistics ................................................................................ 6 6 Player of the Match statistics ............................................................................... 7 End of day review | Day 23 1 1 Group Tables Group A Rank Team Matches Won Lost Tied N/R Net RR For Against Points 1 New Zealand (Q) 5 5 0 0 0 3.09 942/146.3 835/250.0 10 2 Australia (Q) 5 3 1 0 1 1.60 1286/200.0 837/173.1 7 3 Bangladesh (Q) 5 3 1 0 1 0.21 1104/198.1 1072/200.0 7 4 Sri Lanka (Q) 5 3 2 0 0 -0.15 1425/245.4 1488/250.0 6 5 England 5 1 4 0 0 -1.00 1226/250.0 1238/209.4 2 6 Afghanistan 5 1 4 0 0 -1.88 933/249.3 1318/234.3 2 7 Scotland 4 0 4 0 0 -1.42 854/200.0 982/172.3 0 Group B Rank Team Matches Won Lost Tied N/R Net RR For Against Points 1 India (Q) 4 4 0 0 0 2.25 896/158.0 685/200.0 8 2 South Africa 5 3 2 0 0 1.46 1537/247.0 1176/247.0 6 3 Pakistan 5 3 2 0 0 -0.19 1189/247.0 1237/247.0 6 4 Ireland 4 -

Misbah Raajiv Tripathi “Even After Scoring So Many DOHA Runs and So Many Centuries, He Still Wants to Do Better

Sports Monday, June 3, 2019 19 HH Sheikh Mohammed’s Aspetar & Pelligrina triumph Aspetar is best of the field before finding her way through the others 350m at Grand Prix de from the post. Once in the opening, she left no chance to Chantilly; Prix her rivals. Indeed, the closest de Royaumont filly was Malevra, two and a half lengths behind. Je Ne Regrette- for Pelligrina rien completed the podium. Pierre-Charles Boudot TRIBUNE NEWS NETWORK was riding Pelligrina. He DOHA said: “She did very well to- day. She was already very THE HH Sheikh Mohammed pleasing for her first steps bin Khalifa al Thani-owned As- in competition. She has a petar (Al Kazeem) took home lot of stamina and the well- brilliantly the Grand Prix de paced race helped her. She Chantilly (Gr2) at Chantilly, came very easily in front and Paris, on Sunday. slowed down a little. She is Ridden by James Doyle, a very easy filly, who should Aspetar cantered on the out- continue to progress.” side of the field led by Silver- Pelligrina had only run wave (Silver Frost) at a good once and won it on 13th May at pace. He then accelerated in Saint-Cloud. She was passing a the middle of the track before Aspetar (left) and Pelligrina (above) move ahead of the field on the way to winning their respective races at Chantilly, Paris, France, on Sunday. real test today. Bertrand Le Mé- taking the advantage over the tayer, the owner’s representa- leaders 100m from the post. by His Highness Sheikh Mo- soft ground. -

BANGLADESH: from AUTOCRACY to DEMOCRACY (A Study of the Transition of Political Norms and Values)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by KDI School Archives BANGLADESH: FROM AUTOCRACY TO DEMOCRACY (A Study of the Transition of Political Norms and Values) By Golam Shafiuddin THESIS Submitted to School of Public Policy and Global Management, KDI in partial fulfillment of the requirements the degree of MASTER OF PUBLIC POLICY 2002 BANGLADESH: FROM AUTOCRACY TO DEMOCRACY (A Study of the Transition of Political Norms and Values) By Golam Shafiuddin THESIS Submitted to School of Public Policy and Global Management, KDI in partial fulfillment of the requirements the degree of MASTER OF PUBLIC POLICY 2002 Professor PARK, Hun-Joo (David) ABSTRACT BANGLADESH: FROM AUTOCRACY TO DEMOCRACY By Golam Shafiuddin The political history of independent Bangladesh is the history of authoritarianism, argument of force, seizure of power, rigged elections, and legitimacy crisis. It is also a history of sustained campaigns for democracy that claimed hundreds of lives. Extremely repressive measures taken by the authoritarian rulers could seldom suppress, or even weaken, the movement for the restoration of constitutionalism. At times the means adopted by the rulers to split the opposition, create a democratic facade, and confuse the people seemingly served the rulers’ purpose. But these definitely caused disenchantment among the politically conscious people and strengthened their commitment to resistance. The main problems of Bangladesh are now the lack of national consensus, violence in the politics, hartal (strike) culture, crimes sponsored with political ends etc. which contribute to the negation of democracy. Besides, abject poverty and illiteracy also does not make it easy for the democracy to flourish. -

By Mohammed Syful Islam on “Koun Bonega Crorepati

By Mohammed Syful Islam On “Koun Bonega Crorepati” (“Who Will Be The Owner of Crore of Taka”), a popular game show on India’s Zee TV, participants answer general knowledge questions to win one crore taka [one crore is equal to 10 million taka (US$145,571). But Bangladeshi politicians-regardless of name or seniority-do not need a TV game show to quickly earn several crores of taka. Thanks to a recent anti-corruption drive by the interim government that has revealed hundreds of cases of corruption, the Bangladeshi people now know that politicians and government officials have deceived them and earned crores of taka by abusing power. Public opinion surveys from 2001 through 2006 show that people perceive Bangladesh as one of the most corrupt countries in the world, much to the denial of political leaders. “Under the political governments of two ladies-Sheikh Hasina and Begum Khaleda Zia-corruption was made a way of life at all levels, particularly at the corridors of power,” says Golam Haider, a senior journalist at The New Nation newspaper . “It was openly patronized and practiced across the table. Despite the interim government’s anti-corruption efforts, corruption still exists; now it’s happening under the table. The anti-corruption drive is not running on the right track. Corrupt people cannot fight corruption, Haider says. Jasmin Rahman, a master’s student at a government university, says corruption begins at the school level. “A student who fails in school-level examinations still becomes eligible to sit for examinations under the education board, after she or he or their parents pay some bribe to the school authorities in the name of donation,” Rahman says.