BIRDS THAT INJURE GRAIN. Aside from Its Importance As a Principal Source of Food Supply, the Immense Financial Value of the G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

345 Fieldfare Put Your Logo Here

Javier Blasco-Zumeta & Gerd-Michael Heinze Sponsor is needed. Write your name here Put your logo here 345 Fieldfare Fieldfare. Adult. Male (09-I). Song Thrush FIELDFARE (Turdus pilaris ) IDENTIFICATION 25-26 cm. Grey head; red-brown back; grey rump and dark tail; pale underparts; pale flanks spotted black; white underwing coverts; yellow bill with ochre tip. Redwing Fieldfare. Pattern of head, underwing co- verts and flank. SIMILAR SPECIES Song Thrush has orange underwing coverts; Redwing has reddish underwing coverts; Mistle Thrush has white underwing coverts, but lacks pale supercilium and its rump isn’t grey. Mistle Thrush http://blascozumeta.com Write your website here Page 1 Javier Blasco-Zumeta & Gerd-Michael Heinze Sponsor is needed. Write your name here Put your logo here 345 Fieldfare SEXING Male with dark or black tail feathers; red- dish feathers on back with blackish center; most have a broad mark on crown feathers. Female with dark brown tail feathers but not black; dull reddish feathers on back with dark centre (but not blackish); most have a thin mark on crown feathers. CAUTION: some birds of both sexes have similar pattern on crown feathers. Fieldfare. Sexing. Pattern of tail: left male; right fe- male. Fieldfare. Sexing. Pat- AGEING tern of Since this species doesn’t breed in Aragon, only crown feat- 2 age groups can be recognized: hers: top 1st year autumn/2nd year spring with moult male; bot- limit within moulted chestnut inner greater co- tom female. verts and retained juvenile outer greater coverts, shorter and duller with traces of white tips; pointed tail feathers. -

0854 BC Annual Review 04

ann ual review for 2010/11 Saving butte rflies, moths and our environment Highlights of the year Overview by Chairman and Chief Executive In this Annual Review, we celebrate our achievements over the last year and look Several of our most threatened butterflies and moths Secured a core funding grant for Butterfly Conservation ahead to explain our ambitious “2020 vision” for the current decade and beyond. began to recover thanks to our landscape scale projects. Europe from the EU, which enabled the employment of staff for the first time. Successes include the Pearl- bordered Fritillary, Undoubtedly, the most significant success during 2010 is that several of our During the year, we have successfully concluded two of our biggest ever High Brown Fritillary, Duke of Burgundy, Wood White, most threatened species showed signs of recovery directly due to management projects (Moths Count and the South-East Woodlands project) and taken out Small Blue, Grey Carpet and Forester moths. Raised funds to continue our work to save threatened carried out as part of our landscape scale initiatives. Against the background leases on three important new reserves. Our success has been demonstrated species in Scotland, Wales and N. Ireland and for major of decades of decline and habitat loss, these increases show that our by a growth in membership to almost 16,000 and by the continuing support Acquired three new reserves which support important new landscape projects to save the Duke of Burgundy conservation strategy is working. of those members who have responded generously to our appeals and populations of threatened species: Myers Allotment on the South Downs and the Large Blue in Somerset. -

Attraction of Nocturnally Migrating Birds to Artificial Light the Influence

Biological Conservation 233 (2019) 220–227 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Biological Conservation journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/biocon Attraction of nocturnally migrating birds to artificial light: The influence of colour, intensity and blinking mode under different cloud cover conditions T ⁎ Maren Rebkea, , Volker Dierschkeb, Christiane N. Weinera, Ralf Aumüllera, Katrin Hilla, Reinhold Hilla a Avitec Research GbR, Sachsenring 11, 27711 Osterholz-Scharmbeck, Germany b Gavia EcoResearch, Tönnhäuser Dorfstr. 20, 21423 Winsen (Luhe), Germany ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: A growing number of offshore wind farms have led to a tremendous increase in artificial lighting in the marine Continuous and intermittent light environment. This study disentangles the connection of light characteristics, which potentially influence the Light attraction reaction of nocturnally migrating passerines to artificial illumination under different cloud cover conditions. In a Light characteristics spotlight experiment on a North Sea island, birds were exposed to combinations of light colour (red, yellow, Migrating passerines green, blue, white), intensity (half, full) and blinking mode (intermittent, continuous) while measuring their Nocturnal bird migration number close to the light source with thermal imaging cameras. Obstruction light We found that no light variant was constantly avoided by nocturnally migrating passerines crossing the sea. The number of birds did neither differ between observation periods with blinking light of different colours nor compared to darkness. While intensity did not influence the number attracted, birds were drawn more towards continuous than towards blinking illumination, when stars were not visible. Red continuous light was the only exception that did not differ from the blinking counterpart. Continuous green, blue and white light attracted significantly more birds than continuous red light in overcast situations. -

Biodiversity Information Report 13/07/2018

Biodiversity Information Report 13/07/2018 MBB reference: 2614-ARUP Site: Land near Hermitage Green Merseyside BioBank, The Local Biodiversity Estate Barn, Court Hey Park Roby Road, Liverpool Records Centre L16 3NA for North Merseyside Tel: 0151 737 4150 [email protected] Your Ref: None supplied MBB Ref: 2614-ARUP Date: 13/07/2018 Your contact: Amy Martin MBB Contact: Ben Deed Merseyside BioBank biodiversity information report These are the results of your data request relating to an area at Land near Hermitage Green defined by a buffer of 2000 metres around a site described by a boundary you supplied to us (at SJ598944). You have been supplied with the following: records of protected taxa that intersect the search area records of BAP taxa that intersect the search area records of Red Listed taxa that intersect the search area records of other ‘notable’ taxa that intersect the search area records of WCA schedule 9 taxa (including ‘invasive plants’) that intersect the search area a map showing the location of monad and tetrad references that overlap the search area a list of all designated sites that intersect your search area citations, where available, for intersecting Local Wildlife Sites a list of other sites of interest (e.g. Ancient Woodlands) that intersect your search area a map showing such sites a list of all BAP habitats which intersect the search area a map showing BAP habitats a summary of the area for all available mapped Phase 1 and/or NVC habitats found within 500m of your site a map showing such habitats Merseyside BioBank (MBB) is the Local Environmental Records Centre (LERC) for North Merseyside. -

EUROPEAN BIRDS of CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, Trends and National Responsibilities

EUROPEAN BIRDS OF CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, trends and national responsibilities COMPILED BY ANNA STANEVA AND IAN BURFIELD WITH SPONSORSHIP FROM CONTENTS Introduction 4 86 ITALY References 9 89 KOSOVO ALBANIA 10 92 LATVIA ANDORRA 14 95 LIECHTENSTEIN ARMENIA 16 97 LITHUANIA AUSTRIA 19 100 LUXEMBOURG AZERBAIJAN 22 102 MACEDONIA BELARUS 26 105 MALTA BELGIUM 29 107 MOLDOVA BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 32 110 MONTENEGRO BULGARIA 35 113 NETHERLANDS CROATIA 39 116 NORWAY CYPRUS 42 119 POLAND CZECH REPUBLIC 45 122 PORTUGAL DENMARK 48 125 ROMANIA ESTONIA 51 128 RUSSIA BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is a partnership of 48 national conservation organisations and a leader in bird conservation. Our unique local to global FAROE ISLANDS DENMARK 54 132 SERBIA approach enables us to deliver high impact and long term conservation for the beneit of nature and people. BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is one of FINLAND 56 135 SLOVAKIA the six regional secretariats that compose BirdLife International. Based in Brus- sels, it supports the European and Central Asian Partnership and is present FRANCE 60 138 SLOVENIA in 47 countries including all EU Member States. With more than 4,100 staf in Europe, two million members and tens of thousands of skilled volunteers, GEORGIA 64 141 SPAIN BirdLife Europe and Central Asia, together with its national partners, owns or manages more than 6,000 nature sites totaling 320,000 hectares. GERMANY 67 145 SWEDEN GIBRALTAR UNITED KINGDOM 71 148 SWITZERLAND GREECE 72 151 TURKEY GREENLAND DENMARK 76 155 UKRAINE HUNGARY 78 159 UNITED KINGDOM ICELAND 81 162 European population sizes and trends STICHTING BIRDLIFE EUROPE GRATEFULLY ACKNOWLEDGES FINANCIAL SUPPORT FROM THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION. -

Stratford Park Bird Report 2019 Mike Mccrea (Contract Supervisor)

Stratford Park Bird Report 2019 Mike McCrea (Contract Supervisor) (Common Buzzard in Stratford Park Photo: Mike McCrea) Hi All, This month’s Biodiversity Newsletter features a Stratford Park Bird Report for 2019. Mike INTRODUCTION Birds globally are facing increasing challenges; the main drivers being Climate change, agricultural management, hydrological change, urbanisation and invasive non-native species. These factors in the last thirty years have caused the world’s bird populations to decline by 40%. Birds are an indicator species – their presence (or lack thereof) is a sign of the good health (or otherwise) of an ecosystem. The recently published Wild Bird Populations in the UK 1970 – 2018 report shows that many of our familiar birds are still declining, with several doing so at a worrying rate. This downward trend is happening globally in a wide range of habitats. Within the context of global bird distribution, Stratford Park is but a microcosm within the whole picture but as important as any other habitat for wild birds, for it is this park, like many others throughout the UK, which provides important habitats for our birds. Within a snapshot of 30 years the park has lost at least six species of birds, several of which were previously common – bullfinch and spotted flycatcher being the most notable. Others such as Mistle thrush and song thrush have declined at an alarming rate. During the last 10 years we have helped the recovery of many of the park’s bird species through the introduction of next boxes and creating new habitats. The Stratford Park Biodiversity & Landscape Action Plan (2011) has been the catalyst for biodiversity development and a working tool which we have used to identify key areas throughout the park that require conservation measures for the benefit of birds and other animals. -

First Record of Redwing Turdus Iliacus in South America

Guilherme R. R. Brito et al. 316 Bull. B.O.C. 2013 133(4) First record of Redwing Turdus iliacus in South America by Guilherme R. R. Brito, Jorge Bruno Nacinovic & Dante Martins Teixeira Received 15 April 2013 Redwing Turdus iliacus breeds from Iceland to eastern Russia and winters mainly in Europe, east to the Caspian (Collar 2005), with some birds migrating up to 7,000 km (Clement & Hathway 2000, Milwright 2003). It is a winter visitor to Greenland (Clement & Hathway 2000) and a vagrant to both coasts of the USA and Canada (ABA 2002). Vagrants reach North America via two routes. Those on the north-east Atlantic coast have apparently crossed the North Atlantic to reach Greenland, Newfoundland and the USA. Other than a doubtful record at Jamaica Bay, New York, in February 1959 (Young 1959), the frst documented record in North America was at St. Anthony, Newfoundland, on 26 June–11 July 1980 (Vickery 1980, Hall 1981, Montevecchi et al. 1981). Subsequent records are from Newfoundland, Quebec and Pennsylvania, all of singles in February (Clement & Hathway 2000, Denault 2000, Kasir 2005). On the Pacifc coast there are fewer records, and these birds presumably arrive via the Bering Sea (Clement & Hathway 2000, Gibson et al. 2012), in Olympia, Washington, in December 2004–March 2005 (Mlodinow & Aanerud 2008) and Seward, Alaska, in November 2011 (Gibson et al. 2012). In East Asia, T. iliacus has wandered south to Japan, in January (Oozeki et al. 2004). Figure 1. Redwing Turdus iliacus specimen (MN49322) collected on the Ramform Victory, of Espírito Santo, Brazil, 31 December 2001. -

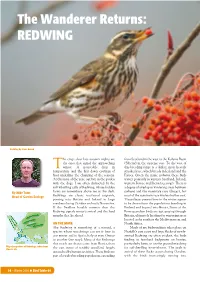

The Wanderer Returns: REDWING

The Wanderer Returns: REDWING Redwing by Steve Round he crisp, clear late autumn nights are from Scotland in the west to the Kolyma Basin the ones that signal the approaching (Siberia) in the extreme east. To the west of T winter. A noticeable drop in this breeding range is a darker, more heavily temperature and the first dawn coatings of streaked race, which breeds in Iceland and the frost underline the changing of the seasons. Faroes. Given the name corburni, these birds At this time of the year, out late in the garden winter primarily in western Scotland, Ireland, with the dogs, I am often distracted by the western France and Iberia (see map). There is soft whistling calls of Redwing, whose hidden a degree of overlap in wintering areas between forms are somewhere above me in the dark. corburni and the nominate race (iliacus), but By Mike Toms Redwings are classic nocturnal migrants, most of the nominate race winters further east. Head of Garden Ecology pouring into Britain and Ireland in large Those iliacus present here in the winter appear numbers during October and early November. to be drawn from the populations breeding in If the Swallow heralds summer then the Finland and beyond into Russia. Some of the Redwing signals winter’s arrival and the hard Fennoscandian birds are just passing through months that lie ahead. Britain, ultimately heading for wintering areas located as far south as the Mediterranean and ON THE MOVE North Africa. The Redwing is something of a nomad, a Much of my birdwatching takes place on species whose wanderings can see it here in Norfolk’s east coast and large flocks of newly- one winter and in Spain, Italy or even Greece arrived Redwing are often evident, the birds in another (see map). -

KERN RED-WINGED BLACKBIRD (Agelaius Phoeniceus Aciculatus) Terri Gallion

II SPECIES ACCOUNTS Andy Birch PDF of Kern Red-winged Blackbird account from: Shuford, W. D., and Gardali, T., editors. 2008. California Bird Species of Special Concern: A ranked assessment of species, subspecies, and distinct populations of birds of immediate conservation concern in California. Studies of Western Birds 1. Western Field Ornithologists, Camarillo, California, and California Department of Fish and Game, Sacramento. Studies of Western Birds No. 1 KERN RED-WINGED BLACKBIRD (Agelaius phoeniceus aciculatus) Terri Gallion Criteria Scores Population Trend 5 Range Trend 0 Population Size 7.5 Range Size 10 Endemism 10 Population Concentration 5 Threats 10 Inyo County Tulare County Kings County Kern County Breeding Range County Boundaries Water Bodies Kilometers 30 15 0 30 Breeding, and perhaps primary year-round, range of the Kern Red-winged Blackbird, a California endemic. Restricted to the Kern River Valley and the Walker Basin of east-central Kern County, where the general outline of the range remains intact but numbers have declined at least slightly. 432 Studies of Western Birds 1:432–436, 2008 Species Accounts California Bird Species of Special Concern SPECIAL CONCERN PRIORITY of the Kern River; Bodfish; and the Walker Basin (Mailliard 1915a, b; van Rossem 1926; Grinnell Currently considered a Bird Species of Special and Miller 1944). Mailliard (1915a) described this Concern (year round), priority 2. Not included on subspecies as limited to a few individuals in the prior special concern lists (Remsen 1978, CDFG Walker Basin and in the Kern River Valley, where 1992). it occurred in small groups and colonies and was “far from numerous.” Grinnell and Miller (1944) REEDING IRD URVEY TATISTICS B B S S stated that irrigated alfalfa fields had increased for- FOR CALIFORNIA aging habitat for the Kern Red-winged Blackbird. -

The Birds of Wimbledon Common & Putney Heath 2016

The Birds of Wimbledon Common & Putney Heath 2016 Marsh Tit 1 The Birds of Wimbledon Common and Putney Heath 2016 The Birds of Wimbledon Common and Putney Heath 2016 here were 94 species recorded on the Common this year, 45 of which bred or probably bred. As T a matter of interest, the overall number of species recorded since records first began in 1974 currently stands at 152, nine of which being flyovers. This has been quite an exciting year on the Common, albeit with the usual ups and downs. There were three outstanding observations, in the form of Marsh Tit, European Bee-eater and Dartford Warbler, with the Marsh Tit providing the first positive evidence of breeding on the Common since 1979. My thanks are due to Jan Wilczur for his help in establishing this record; whilst the European Bee-eater seen and photographed on the 19th May by Magnus Andersson was even more remarkable, it being, according to the last sighting in the London Bird Report of 2007, possibly only the ninth to be recorded in the London area. And, last but not least, was the Dartford Warbler found at Ladies Mile on the 29th September, a bird which remained in the area until at least 19th Dec.; searching for previous records of this rare visitor, it would seem that this may have been the first record since 1938, a pair having bred in 1936. Other notable breeding species this year included the successful breeding of two pairs of Swallows, both nesting in out-buildings at the Windmill complex, one of which produced two broods; meanwhile three Willow Warbler territories were established, this being the best number since 2010, and at least two pair of Reed Buntings held territories. -

Ring23-1.Vp:Corelventura

NEW COMPREHENSIVE SYSTEMATIC DATA CONCERNING THE TIME OF NOCTURNAL DEPARTURE IN SOME PASSERINE MIGRANTS IN AUTUMN Casimir V. Bolshakov and Victor N. Bulyuk ABSTRACT Bolshakov C. V., Bulyuk V. N. 2001. New comprehensive systematic data concerning the time of nocturnal departure in some passerine migrants in autumn. Ring 23, 1-2: 131-137. Time of nocturnal departures of some passerine migrants (Robin Erithacus rubecula, Song Thrush Turdus philomelos, Blackbird T. merula, Redwing T. iliacus, Goldcrest Regulus regulus, and a pooled group of long-distance migrants, mainly warblers, flycatchers and red- starts) from a stopover site on the Courish Spit of the Baltic Sea was studied by searchlight method throughout the whole night from sunset to sunrise. Timing of take-off activity are subject to broad-scale variation between different species, during the season and from night to night. Overall departure period comprises at least 7 hours in long-distance migrants, 9 h in Robin, Song Thrush and Goldcrest, and as much as 11 h in Blackbird and Redwing. Median departure time in different species varies from 152 to 386 min after sunset. C. V. Bolshakov, V. N. Bulyuk, Biological Station Rybachy, Zoological Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences, Rybachy 238535, Kaliningrad Region, Russia, E-mail: Rybachy@ bioryb.koenig.su Key words: nocturnal departure, take-off activity, passerine nocturnal migrants, searchlight method, autumn migration INTRODUCTION Diel timing of two most important behaviours of migrating birds flight and stopover is a very fascinating and promising field of research. Current views con- cerning the diel timing of flight and stopover in different avian taxa are however based on hypothetical models, with few exceptions (Kerlinger and Moore 1989, Al- erstam 1990, Berthold 1993). -

In Southern Norway Determined from Prey Remains and Video Recordings

Ornis Fennica 84:97–104. 2007 Diet of Common Buzzards (Buteo buteo) in southern Norway determined from prey remains and video recordings Vidar Selås, Reidar Tveiten & Ole Martin Aanonsen Selås, V., Department of Ecology and Natural Resource Management, Norwegian Uni- versity of Life Sciences, P.O. Box 5003, NO-1432 Ås, Norway. [email protected] (*Corresponding author) Tveiten, R., Department of Ecology and Natural Resource Management, Norwegian Uni- versity of Life Sciences, P.O. Box 5003, NO-1432 Ås, Norway Aanonsen, O.M., Department of Ecology and Natural Resource Management, Norwe- gian University of Life Sciences, P.O. Box 5003, NO-1432 Ås, Norway Received 8 September 2006, revised 21 December 2006, accepted 8 February 2007 We examined the diet of six breeding Common Buzzard (Buteo buteo) pairs in southern Norway, by analysing pellets and prey remains collected around and in nests, and by video recording prey delivery at the nests. Mammals, birds and reptiles were the major prey groups. Amphibians were underestimated when identified from pellets and prey remains compared to video recording, while birds >120 g were overestimated. Selection of avian prey was studied by comparing the proportions of different weight groups of birds among prey with their proportions in the bird community, as estimated by point counts around each nest. Common Buzzards selectively preyed upon medium-sized birds and neglected many of the numerous small passerines. 1. Introduction remains and regurgitated pellets (e.g. Spidsø & Selås 1988, Mañosa & Cordero 1992, Graham et The majority of studies on the diet of Common al. 1995, Reif et al.