Do Passerine Birds Utilise Artificial Light to Prolong Their Diurnal Activity During Winter at Northern Latitudes?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

345 Fieldfare Put Your Logo Here

Javier Blasco-Zumeta & Gerd-Michael Heinze Sponsor is needed. Write your name here Put your logo here 345 Fieldfare Fieldfare. Adult. Male (09-I). Song Thrush FIELDFARE (Turdus pilaris ) IDENTIFICATION 25-26 cm. Grey head; red-brown back; grey rump and dark tail; pale underparts; pale flanks spotted black; white underwing coverts; yellow bill with ochre tip. Redwing Fieldfare. Pattern of head, underwing co- verts and flank. SIMILAR SPECIES Song Thrush has orange underwing coverts; Redwing has reddish underwing coverts; Mistle Thrush has white underwing coverts, but lacks pale supercilium and its rump isn’t grey. Mistle Thrush http://blascozumeta.com Write your website here Page 1 Javier Blasco-Zumeta & Gerd-Michael Heinze Sponsor is needed. Write your name here Put your logo here 345 Fieldfare SEXING Male with dark or black tail feathers; red- dish feathers on back with blackish center; most have a broad mark on crown feathers. Female with dark brown tail feathers but not black; dull reddish feathers on back with dark centre (but not blackish); most have a thin mark on crown feathers. CAUTION: some birds of both sexes have similar pattern on crown feathers. Fieldfare. Sexing. Pattern of tail: left male; right fe- male. Fieldfare. Sexing. Pat- AGEING tern of Since this species doesn’t breed in Aragon, only crown feat- 2 age groups can be recognized: hers: top 1st year autumn/2nd year spring with moult male; bot- limit within moulted chestnut inner greater co- tom female. verts and retained juvenile outer greater coverts, shorter and duller with traces of white tips; pointed tail feathers. -

Trichomonosis in Garden Birds

Trichomonosis in Garden Birds Agent Trichomonas gallinae is a single-celled protozoan parasite that can cause a disease known as trichomonosis in garden birds. Species affected Trichomonosis is known to affect pigeons and doves in the UK, including woodpigeons (Columba palumbus), feral pigeons (Columbia livia)and collared doves (Streptopelia decaocto) that routinely visit garden feeders, and the endangered turtle dove (Streptopelia turtur), which sometimes feed on food spills from bird tables in rural areas. It can also affect birds of prey that feed on other birds that are infected with the parasite. The common name for the disease in pigeons and doves is “canker” and in birds of prey the disease is also known as “frounce”. Trichomonosis was first seen in British finch species in summer 2005 with subsequent epidemic spread throughout Great Britain and across Europe. Whilst greenfinch (Chloris chloris) and chaffinch (Fringilla coelebs) are the species that have been most frequently affected by this emerging infectious disease, many other garden bird species which are gregarious and feed on seed, including the house sparrow (Passer domesticus), siskin (Carduelis spinus), goldfinch (Carduelis carduelis) and bullfinch (Pyrrhula pyrrhula), are susceptible to the condition. Other garden bird species that typically feed on invertebrates, such as blackbird (Turdus merula) and dunnock (Prunella modularis) are also susceptible: investigations indicate they are not commonly affected but that this tends to be observed in gardens where outbreaks of disease involving large numbers of finches occur. Pathology Trichomonas gallinae typically causes disease at the back of the throat and in the gullet. Signs of disease In addition to showing signs of general illness, for example lethargy and fluffed-up plumage, affected birds may drool saliva, regurgitate food, have difficulty in swallowing or show laboured breathing. -

What Is So Rare?

WHAT IS SO RARE? As a Fieldfare in April? In Massachusetts, perhaps only a Western Reef Heron or a White-faced Ibis. April here is a month of avian surprises. The 1986 birdwatching spring was off to a happy start with the discovery by schoolteacher Ralph Richards, during a lonely vigil on the cold and rainy Sunday of April 6, of a Fieldfare Turdus pilaris) in a Concord cornfield near the Sudbury River. According ta a bulletin promptly issued by the Massachusetts Audubon Society, this is a first state record, and there have been, s-ince 1878, ten prior records in North America, the most recent being the occurrence of four Fieldfares in St. John's, Newfoundland, from December 1985 to mid-January 1986. "It seems not unlikely that the Massachusetts bird originated with the same midwinter flight that brought the Newfoundland birds to North America. ..." In winter, the Fieldfare ranges from southern Scandinavia, the British Isles, and central Europe south to the Mediterranean. Outside of the breeding season, the bird's habitat choice is open fields and pastures, where it occurs gregariously in large flocks, often accompanied by Redwings (Turdus iliacus). The Fieldfare nests in northern Scandinavia (it is Norway's most common thrush), in north and central continental Europe east to Siberia, and also in Iceland and southern Greenland. The story of the establishment of the disjunct Greenland population is well documented. In January 1937, a strong southeast gale swept a flock of Fieldfares across Europe and the Atlantic to the island of Jan Mayen and the Greenland coast. -

New Zealand Comprehensive II Trip Report 31St October to 16Th November 2016 (17 Days)

New Zealand Comprehensive II Trip Report 31st October to 16th November 2016 (17 days) The Critically Endangered South Island Takahe by Erik Forsyth Trip report compiled by Tour Leader: Erik Forsyth RBL New Zealand – Comprehensive II Trip Report 2016 2 Tour Summary New Zealand is a must for the serious seabird enthusiast. Not only will you see a variety of albatross, petrels and shearwaters, there are multiple- chances of getting out on the high seas and finding something unusual. Seabirds dominate this tour and views of most birds are alongside the boat. There are also several land birds which are unique to these islands: kiwis - terrestrial nocturnal inhabitants, the huge swamp hen-like Takahe - prehistoric in its looks and movements, and wattlebirds, the saddlebacks and Kokako - poor flyers with short wings Salvin’s Albatross by Erik Forsyth which bound along the branches and on the ground. On this tour we had so many highlights, including close encounters with North Island, South Island and Little Spotted Kiwi, Wandering, Northern and Southern Royal, Black-browed, Shy, Salvin’s and Chatham Albatrosses, Mottled and Black Petrels, Buller’s and Hutton’s Shearwater and South Island Takahe, North Island Kokako, the tiny Rifleman and the very cute New Zealand (South Island wren) Rockwren. With a few members of the group already at the hotel (the afternoon before the tour started), we jumped into our van and drove to the nearby Puketutu Island. Here we had a good introduction to New Zealand birding. Arriving at a bay, the canals were teeming with Black Swans, Australasian Shovelers, Mallard and several White-faced Herons. -

New Data on the Chewing Lice (Phthiraptera) of Passerine Birds in East of Iran

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/244484149 New data on the chewing lice (Phthiraptera) of passerine birds in East of Iran ARTICLE · JANUARY 2013 CITATIONS READS 2 142 4 AUTHORS: Behnoush Moodi Mansour Aliabadian Ferdowsi University Of Mashhad Ferdowsi University Of Mashhad 3 PUBLICATIONS 2 CITATIONS 110 PUBLICATIONS 393 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Ali Moshaverinia Omid Mirshamsi Ferdowsi University Of Mashhad Ferdowsi University Of Mashhad 10 PUBLICATIONS 17 CITATIONS 54 PUBLICATIONS 152 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Available from: Omid Mirshamsi Retrieved on: 05 April 2016 Sci Parasitol 14(2):63-68, June 2013 ISSN 1582-1366 ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE New data on the chewing lice (Phthiraptera) of passerine birds in East of Iran Behnoush Moodi 1, Mansour Aliabadian 1, Ali Moshaverinia 2, Omid Mirshamsi Kakhki 1 1 – Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Faculty of Sciences, Department of Biology, Iran. 2 – Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Department of Pathobiology, Iran. Correspondence: Tel. 00985118803786, Fax 00985118763852, E-mail [email protected] Abstract. Lice (Insecta, Phthiraptera) are permanent ectoparasites of birds and mammals. Despite having a rich avifauna in Iran, limited number of studies have been conducted on lice fauna of wild birds in this region. This study was carried out to identify lice species of passerine birds in East of Iran. A total of 106 passerine birds of 37 species were captured. Their bodies were examined for lice infestation. Fifty two birds (49.05%) of 106 captured birds were infested. Overall 465 lice were collected from infested birds and 11 lice species were identified as follow: Brueelia chayanh on Common Myna (Acridotheres tristis), B. -

American Robin

American Robin DuPage Birding Club, 2020 American Robin Appearance A chunky, heavy-bodied bird with a relatively small dark head. Sexually dimorphic, meaning the male and female look different. American Robins are a uniform dark gray with a brick red breast. Female Male Females are a lighter gray with a lighter breast. Males tend to be darker with a brighter red breast. Males are larger than females. Photos: Elmarie Von Rooyen (left), Jackie Tilles (right) DuPage Birding Club, 2020 2 American Robin Appearance American Robins are a medium-size bird with a length of about ten inches. They are so common that they are a good bird to compare size with when you come across an unknown bird. Is the bird bigger than an American Robin or smaller than an American Robin? Judging the size of a bird is very helpful in identifying an unknown bird. Chart: The Cornell Lab, All About Birds https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/American_Robin/id DuPage Birding Club, 2020 3 American Robin Appearance Juvenile American Robins have a speckled breast with a tint of rusty red. Photos: Natalie McFaul DuPage Birding Club, 2020 4 American Robin Sounds From The Cornell Lab of Ornithology: https://www.birds.cornell.edu/home/ SONGS The musical song of the American Robin is a familiar sound of spring. It’s a string of 10 or so clear whistles assembled from a few often- repeated syllables, and often described as cheerily, cheer up, cheer up, cheerily, cheer up. The syllables rise and fall in pitch but are delivered at a steady rhythm, with a pause before the bird begins singing again. -

Phylogeography of Finches and Sparrows

In: Animal Genetics ISBN: 978-1-60741-844-3 Editor: Leopold J. Rechi © 2009 Nova Science Publishers, Inc. Chapter 1 PHYLOGEOGRAPHY OF FINCHES AND SPARROWS Antonio Arnaiz-Villena*, Pablo Gomez-Prieto and Valentin Ruiz-del-Valle Department of Immunology, University Complutense, The Madrid Regional Blood Center, Madrid, Spain. ABSTRACT Fringillidae finches form a subfamily of songbirds (Passeriformes), which are presently distributed around the world. This subfamily includes canaries, goldfinches, greenfinches, rosefinches, and grosbeaks, among others. Molecular phylogenies obtained with mitochondrial DNA sequences show that these groups of finches are put together, but with some polytomies that have apparently evolved or radiated in parallel. The time of appearance on Earth of all studied groups is suggested to start after Middle Miocene Epoch, around 10 million years ago. Greenfinches (genus Carduelis) may have originated at Eurasian desert margins coming from Rhodopechys obsoleta (dessert finch) or an extinct pale plumage ancestor; it later acquired green plumage suitable for the greenfinch ecological niche, i.e.: woods. Multicolored Eurasian goldfinch (Carduelis carduelis) has a genetic extant ancestor, the green-feathered Carduelis citrinella (citril finch); this was thought to be a canary on phonotypical bases, but it is now included within goldfinches by our molecular genetics phylograms. Speciation events between citril finch and Eurasian goldfinch are related with the Mediterranean Messinian salinity crisis (5 million years ago). Linurgus olivaceus (oriole finch) is presently thriving in Equatorial Africa and was included in a separate genus (Linurgus) by itself on phenotypical bases. Our phylograms demonstrate that it is and old canary. Proposed genus Acanthis does not exist. Twite and linnet form a separate radiation from redpolls. -

A Report of Brambling Fringilla Montifringilla from Mandala Road, Arunachal Pradesh Qupeleio De Souza

136 Indian BirDS VOL. 10 NO. 5 (PUBL. 2 NOVEMBER 2015) and the Middle East (Ali & Ripley 1986). However, observations of the Rosy Starling in the sub-Himalayan or Himalayan areas are very rare (please see distribution map in Grimmett et al. 2011: 404). Published bird checklists, relevant to the Doon Valley in particular (Pandey et al. 1994; Mohan 1996; Singh 2000), and for similar landscapes in the region (Sharma et al. 2003) have no record of the Rosy Starling. The bird is also not listed in the official checklist of birds published by the Uttarakhand Forest Department (Mohan & Sinha 2003). Hence, according to the best of my knowledge, this species has never been observed in Uttarakhand and this sighting is a new record for the state. Since only a single individual was seen of this otherwise highly gregarious bird, it is likely that the Rosy Starling I observed was a vagrant. Acknowledgements I am grateful to Mohammed Bashir for assistance in field, and Soumya Prasad for support. Photo: Raman Kumar References Ali, S., & Ripley, S. D., 1986. Handbook of the birds of India and Pakistan together with those of Bangladesh, Nepal, Bhutan and Sri Lanka. Cuckoo-shrikes to babaxes. 2nd (Hardback) ed. Delhi: (Sponsored by Bombay Natural History Society.) Oxford University Press. Vol. 5 of 10 vols. Pp. i–xvi, 1–278+2+8 ll. 126. Rosy Starling feeding on Mallotus sp. tree, Doon Valley. Champion, H. G., & Seth, S. K., 1968. A revised survey of the forest types of India. Government of India, Delhi. Grimmett, R., Inskipp, C., & Inskipp, T., 2011. -

Developing Methods for the Field Survey and Monitoring of Breeding Short-Eared Owls (Asio Flammeus) in the UK: Final Report from Pilot Fieldwork in 2006 and 2007

BTO Research Report No. 496 Developing methods for the field survey and monitoring of breeding Short-eared owls (Asio flammeus) in the UK: Final report from pilot fieldwork in 2006 and 2007 A report to Scottish Natural Heritage Ref: 14652 Authors John Calladine, Graeme Garner and Chris Wernham February 2008 BTO Scotland School of Biological and Environmental Sciences, University of Stirling, Stirling, FK9 4LA Registered Charity No. SC039193 ii CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES................................................................................................................... iii LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................v LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................v LIST OF APPENDICES...........................................................................................................vi SUMMARY.............................................................................................................................vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................... viii CRYNODEB............................................................................................................................xii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS....................................................................................................xvi 1. BACKGROUND AND AIMS...........................................................................................2 -

Implications of Conspecific Background Noise for Features of Blue Tit, Cyanistes Caeruleus, Communication Networks at Dawn

J Ornithol (2007) 148:123–128 DOI 10.1007/s10336-006-0116-y ORIGINAL ARTICLE Implications of conspecific background noise for features of blue tit, Cyanistes caeruleus, communication networks at dawn Angelika Poesel Æ Torben Dabelsteen Æ Simon Boel Pedersen Received: 3 January 2006 / Revised: 8 November 2006 / Accepted: 8 November 2006 / Published online: 5 December 2006 Ó Dt. Ornithologen-Gesellschaft e.V. 2006 Abstract Communication among animals often com- may potentially constrain the perception of singing prises several signallers and receivers within the sig- patterns and may constitute costs for eavesdroppers. nal’s transmission range. In such communication On the other hand, signallers may position themselves networks, individuals can extract information about strategically and privatise their interactions. differences in relative performance of conspecifics by eavesdropping on their signalling interactions. In Keywords Communication network Á Cyanistes songbirds, information can be encoded in the timing of caeruleus Á Singing interaction signals, which either alternate or overlap, and both male and female receivers may utilise this information when engaging in territorial interactions or making Introduction reproductive decisions, respectively. We investigated how conspecific background noise at dawn may overlay Territorial animals form neighbourhoods of several and possibly constrain the perception of such singing individuals within signalling and receiving range (see patterns. We simulated a small communication net- examples in McGregor 2005). In order to defend ter- work of blue tits, Cyanistes caeruleus, at dawn in ritorial space successfully, it may be advantageous to spring. Two loudspeakers simulated a singing interac- gather information about competitors and thus be able tion which was recorded from four different receiver to adjust responses to an opponent’s strength. -

Progress in the Development of an Eurasian-African Bird Migration Atlas

CONVENTION ON UNEP/CMS/COP13/Inf.20 MIGRATORY 10 February 2020 SPECIES Original: English 13th MEETING OF THE CONFERENCE OF THE PARTIES Gandhinagar, India, 17 - 22 February 2020 Agenda Item 25 PROGRESS IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF AN EURASIAN-AFRICAN BIRD MIGRATION ATLAS (Submitted by the European Union of Bird Ringing (EURING) and the Institute of Avian Research) Summary: The African-Eurasian Bird Migration Atlas is being developed under the auspices of CMS in the framework of a Global Animal Migration Atlas, of which it constitutes a module. The African-Eurasian Bird Migration Atlas is being developed and compiled by the European Union of Bird Ringing (EURING) under a Project Cooperation Agreement (PCA) between the CMS Secretariat and the Institute of Avian Research, acting on behalf of EURING. The development of the African-Eurasian Bird Migration Atlas is funded with the contribution granted by the Government of Italy under the Migratory Species Champion Programme. This information document includes a progress report on the development of the various components of the project. The project is expected to be completed in 2021. UNEP/CMS/COP13/Inf.20 Eurasian-African Bird Migration Atlas progress report February 2020 Stephen Baillie1, Franz Bairlein2, Wolfgang Fiedler3, Fernando Spina4, Kasper Thorup5, Sam Franks1, Dorian Moss1, Justin Walker1, Daniel Higgins1, Roberto Ambrosini6, Niccolò Fattorini6, Juan Arizaga7, Maite Laso7, Frédéric Jiguet8, Boris Nikolov9, Henk van der Jeugd10, Andy Musgrove1, Mark Hammond1 and William Skellorn1. A report to the Convention on Migratory Species from the European Union for Bird Ringing (EURING) and the Institite of Avian Research, Wilhelmshaven, Germany 1. British Trust for Ornithology, Thetford, IP24 2PU, UK 2. -

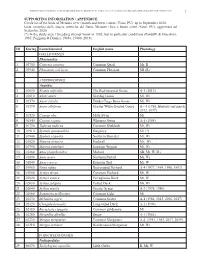

1 ID Euring Latin Binomial English Name Phenology Galliformes

BIRDS OF METAURO RIVER: A GREAT ORNITHOLOGICAL DIVERSITY IN A SMALL ITALIAN URBANIZING BIOTOPE, REQUIRING GREATER PROTECTION 1 SUPPORTING INFORMATION / APPENDICE Check list of the birds of Metauro river (mouth and lower course / Fano, PU), up to September 2020. Lista completa delle specie ornitiche del fiume Metauro (foce e basso corso /Fano, PU), aggiornata ad Settembre 2020. (*) In the study area 1 breeding attempt know in 1985, but in particolar conditions (Pandolfi & Giacchini, 1985; Poggiani & Dionisi, 1988a, 1988b, 2019). ID Euring Latin binomial English name Phenology GALLIFORMES Phasianidae 1 03700 Coturnix coturnix Common Quail Mr, B 2 03940 Phasianus colchicus Common Pheasant SB (R) ANSERIFORMES Anatidae 3 01690 Branta ruficollis The Red-breasted Goose A-1 (2012) 4 01610 Anser anser Greylag Goose Mi, Wi 5 01570 Anser fabalis Tundra/Taiga Bean Goose Mi, Wi 6 01590 Anser albifrons Greater White-fronted Goose A – 4 (1986, february and march 2012, 2017) 7 01520 Cygnus olor Mute Swan Mi 8 01540 Cygnus cygnus Whooper Swan A-1 (1984) 9 01730 Tadorna tadorna Common Shelduck Mr, Wi 10 01910 Spatula querquedula Garganey Mr (*) 11 01940 Spatula clypeata Northern Shoveler Mr, Wi 12 01820 Mareca strepera Gadwall Mr, Wi 13 01790 Mareca penelope Eurasian Wigeon Mr, Wi 14 01860 Anas platyrhynchos Mallard SB, Mr, W (R) 15 01890 Anas acuta Northern Pintail Mi, Wi 16 01840 Anas crecca Eurasian Teal Mr, W 17 01960 Netta rufina Red-crested Pochard A-4 (1977, 1994, 1996, 1997) 18 01980 Aythya ferina Common Pochard Mr, W 19 02020 Aythya nyroca Ferruginous