The Importance of Landscape Structure for Nest Defence in the Eurasian Treecreeper Certhia Familiaris

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Best of the Baltic - Bird List - July 2019 Note: *Species Are Listed in Order of First Seeing Them ** H = Heard Only

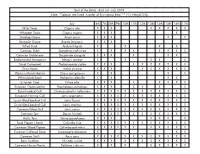

Best of the Baltic - Bird List - July 2019 Note: *Species are listed in order of first seeing them ** H = Heard Only July 6th 7th 8th 9th 10th 11th 12th 13th 14th 15th 16th 17th Mute Swan Cygnus olor X X X X X X X X Whopper Swan Cygnus cygnus X X X X Greylag Goose Anser anser X X X X X Barnacle Goose Branta leucopsis X X X Tufted Duck Aythya fuligula X X X X Common Eider Somateria mollissima X X X X X X X X Common Goldeneye Bucephala clangula X X X X X X Red-breasted Merganser Mergus serrator X X X X X Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo X X X X X X X X X X Grey Heron Ardea cinerea X X X X X X X X X Western Marsh Harrier Circus aeruginosus X X X X White-tailed Eagle Haliaeetus albicilla X X X X Eurasian Coot Fulica atra X X X X X X X X Eurasian Oystercatcher Haematopus ostralegus X X X X X X X Black-headed Gull Chroicocephalus ridibundus X X X X X X X X X X X X European Herring Gull Larus argentatus X X X X X X X X X X X X Lesser Black-backed Gull Larus fuscus X X X X X X X X X X X X Great Black-backed Gull Larus marinus X X X X X X X X X X X X Common/Mew Gull Larus canus X X X X X X X X X X X X Common Tern Sterna hirundo X X X X X X X X X X X X Arctic Tern Sterna paradisaea X X X X X X X Feral Pigeon ( Rock) Columba livia X X X X X X X X X X X X Common Wood Pigeon Columba palumbus X X X X X X X X X X X Eurasian Collared Dove Streptopelia decaocto X X X Common Swift Apus apus X X X X X X X X X X X X Barn Swallow Hirundo rustica X X X X X X X X X X X Common House Martin Delichon urbicum X X X X X X X X White Wagtail Motacilla alba X X -

Multiple Fragmented Habitat-Patch Use in an Urban Breeding Passerine, the Short-Toed Treecreeper

RESEARCH ARTICLE Multiple fragmented habitat-patch use in an urban breeding passerine, the Short-toed Treecreeper Katherine R. S. SnellID*, Rie B. E. Jensen, Troels E. Ortvad, Mikkel Willemoes, Kasper Thorup Center for Macroecology, Evolution and Climate, Natural History Museum of Denmark, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark a1111111111 * [email protected] a1111111111 a1111111111 a1111111111 a1111111111 Abstract Individual responses of wild birds to fragmented habitat have rarely been studied, despite large-scale habitat fragmentation and biodiversity loss resulting from widespread urbanisa- tion. We investigated the spatial ecology of the Short-toed Treecreeper Certhia brachydac- OPEN ACCESS tyla, a tiny, resident, woodland passerine that has recently colonised city parks at the Citation: Snell KRS, Jensen RBE, Ortvad TE, northern extent of its range. High resolution spatiotemporal movements of this obligate tree- Willemoes M, Thorup K (2020) Multiple living species were determined using radio telemetry within the urbanized matrix of city fragmented habitat-patch use in an urban breeding passerine, the Short-toed Treecreeper. PLoS ONE parks in Copenhagen, Denmark. We identified regular edge crossing behaviour, novel in 15(1): e0227731. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. woodland birds. While low numbers of individuals precluded a comprehensive characterisa- pone.0227731 tion of home range for this population, we were able to describe a consistent behaviour Editor: Jorge RamoÂn LoÂpez-Olvera, Universitat which has consequences for our understanding of animal movement in urban ecosystems. Autònoma de Barcelona, SPAIN We report that treecreepers move freely, and apparently do so regularly, between isolated Received: July 10, 2019 habitat patches. This behaviour is a possible driver of the range expansion in this species Accepted: December 29, 2019 and may contribute to rapid dispersal capabilities in certain avian species, including Short- toed Treecreepers, into northern Europe. -

EUROPEAN BIRDS of CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, Trends and National Responsibilities

EUROPEAN BIRDS OF CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, trends and national responsibilities COMPILED BY ANNA STANEVA AND IAN BURFIELD WITH SPONSORSHIP FROM CONTENTS Introduction 4 86 ITALY References 9 89 KOSOVO ALBANIA 10 92 LATVIA ANDORRA 14 95 LIECHTENSTEIN ARMENIA 16 97 LITHUANIA AUSTRIA 19 100 LUXEMBOURG AZERBAIJAN 22 102 MACEDONIA BELARUS 26 105 MALTA BELGIUM 29 107 MOLDOVA BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 32 110 MONTENEGRO BULGARIA 35 113 NETHERLANDS CROATIA 39 116 NORWAY CYPRUS 42 119 POLAND CZECH REPUBLIC 45 122 PORTUGAL DENMARK 48 125 ROMANIA ESTONIA 51 128 RUSSIA BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is a partnership of 48 national conservation organisations and a leader in bird conservation. Our unique local to global FAROE ISLANDS DENMARK 54 132 SERBIA approach enables us to deliver high impact and long term conservation for the beneit of nature and people. BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is one of FINLAND 56 135 SLOVAKIA the six regional secretariats that compose BirdLife International. Based in Brus- sels, it supports the European and Central Asian Partnership and is present FRANCE 60 138 SLOVENIA in 47 countries including all EU Member States. With more than 4,100 staf in Europe, two million members and tens of thousands of skilled volunteers, GEORGIA 64 141 SPAIN BirdLife Europe and Central Asia, together with its national partners, owns or manages more than 6,000 nature sites totaling 320,000 hectares. GERMANY 67 145 SWEDEN GIBRALTAR UNITED KINGDOM 71 148 SWITZERLAND GREECE 72 151 TURKEY GREENLAND DENMARK 76 155 UKRAINE HUNGARY 78 159 UNITED KINGDOM ICELAND 81 162 European population sizes and trends STICHTING BIRDLIFE EUROPE GRATEFULLY ACKNOWLEDGES FINANCIAL SUPPORT FROM THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION. -

Certhia Familiaris

Report under the Article 12 of the Birds Directive European Environment Agency Period 2008-2012 European Topic Centre on Biological Diversity Certhia familiaris Annex I No International action plan No Eurasian Treecreeper, Certhia familiaris, is a species of passerine bird in the treecreeper family found in woodland and forest ecosystems. It is a widespread breeder across much of Europe, but patchily distributed in the South-West. This species inhabits forest and woodland, generally requiring well-grown trees with many cracks and crevices in the bark for foraging, roosting and nesting. It tends to favour older stands of spruce (Picea), but habitat preferences are complex and apparently affected by presence or absence of Certhia brachydactyla (European Red List 2015). Certhia familiaris has a breeding population size of 2790000-5460000 pairs and a breeding range size of 2240000 square kilometres in the EU27. The breeding population trend in the EU27 is Stable in the short term and Stable in the long term. The EU population status of Certhia familiaris was assessed as Secure, because the species does not meet any of the IUCN Red List criteria for threatened or Near Threatened, or the criteria for Depleted or Declining (the EU27 population or range has not declined by 20% or more since 1980). Page 1 Certhia familiaris Report under the Article 12 of the Birds Directive Assessment of status at the European level Breeding Breeding range Winter population Winter Breeding population trend Range trend trend Population population population size area status Short Long Short Long size Short Long term term term term term term 2790000 - 5460000 p 0 0 2240000 Secure See the endnotes for more informationi Page 2 Certhia familiaris Report under the Article 12 of the Birds Directive Page 3 Certhia familiaris Report under the Article 12 of the Birds Directive Trends at the Member State level Breeding Breeding range Winter population Winter % in Breeding population trend Range trend trend MS/Ter. -

Get Our Falsterbo Bird Species Checklist Here!

Diving Ducks (cont.) Cormorants Birds of Prey (cont.) Greater Scaup Great Cormorant Common Kestrel Bird Species List Common Eider Herons, Storks, Ibises Red-Footed Falcon King Eider Great Bittern Merlin Falsterbo, Sweden Steller's Eider Little Egret Eurasian Hobby Long-Tailed Duck Great Egret Eleonora'S Falcon Swans Common Scoter Grey Heron Gyr Falcon Mute Swan Velvet Scoter Purple Heron Peregrine Falcon Tundra Swan Common Goldeneye Black Stork Rails & Crakes Whooper Swan Sawbills White Stork Water Rail Geese Smew Glossy Ibis Spotted Crake Bean Goose Red-Breasted Merganser Eurasian Spoonbill Corn Crake Pink-Footed Goose Goosander Birds of Prey Common Moorhen Greater White-Fronted Goose Partridges & Pheasants European Honey Buzzard Common Coot Lesser White-Fronted Goose Grey Partridge Black-Winged Kite Cranes Greylag Goose Common Quail Black Kite Common Crane Canada Goose Common Pheasant Red Kite Demoiselle Crane Barnacle Goose Loons (Divers) White-Tailed Eagle Bustards Brent Goose Red-Throated Diver Egyptian Vulture Great Bustard Red-Breasted Goose Black-Throated Diver Eurasian Griffon Vulture Waders Egyptian Goose Great Northern Diver Short-Toed Eagle Eurasian Oystercatcher Dabbling Ducks Yellow-Billed Diver Western Marsh Harrier Black-Winged Stilt Ruddy Shelduck Grebes Hen Harrier Pied Avocet Common Shelduck Little Grebe Pallid Harrier Stone-Curlew Eurasian Wigeon Great Crested Grebe Montagu's Harrier Collared Pratincole American Wigeon Red-Necked Grebe Northern Goshawk Oriental Pratincole Gadwall Slavonian Grebe Eurasian Sparrowhawk -

2019 Irish Seabirds & Whales Trip Report

Shearwater Wildlife Tours/Yorkshire Coast Nature Irish Seabirds and Cetaceans Adventure Tour 18th to 22nd July 2019 Trip Report written by Niall T. Keogh Trip Organiser: Paul Connaughton and Richard Baines Tour Leaders: Mark Pearson (YCN) and Niall T. Keogh (SWT) Shearwater Wildlife Tours Yorkshire Coast Nature Cover pic: juvenile Wilson’s Storm-petrel © Mark Pearson Day 1: Thursday 18th July The 2019 Irish Adventure started at Cork Airport where participants and tour leaders met up, hopped in a bus and headed west for wind, waves, dolphins and seabirds! West Cork is well known for its rugged coastline, featuring bays, coves and estuaries aplenty where excellent sites for waterbirds can be found around almost every bend in the road. Our first stop on the tour was Kinsale Marsh. Flocks of Icelandic Black-tailed Godwits put on a good show here along with other early returning waterbird migrants such as Shelduck, Curlew, Redshank, a few Common Sandpipers, Greenshank and a single Knot. After that it was on to Kinsale Pier where the rocky shore produced 15 Mediterranean Gulls, some Sandwich Terns, Shags, Rock Pipits and good views of Hooded Crows! We got our first look at Manx Shearwater here as a foraging flock wheeled around offshore. House Martins buzzed about before an excellent lunch was laid on. With the scenic Old Head of Kinsale just down the road we made our way over to check out the cliff nesting seabird colony there. Even though activity generally winds down at this stage of the summer, it was still a busy view across the steep cliffs where Kittiwake, Guillemot, Razorbill and Fulmar could be seen along with Black Guillemots in the water below. -

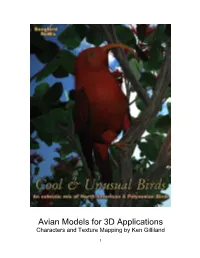

Creating a Songbird Remix Bird with Poser Or DAZ Studio 5 Using Conforming Crests with Poser 6 Using Conforming Crests with DAZ Studio 8

Avian Models for 3D Applications Characters and Texture Mapping by Ken Gilliland 1 Songbird ReMix Cool & Unusual Birds Contents Manual Introduction 3 Overview and Use 3 Conforming Crest Quick Reference 4 Creating a Songbird ReMix Bird with Poser or DAZ Studio 5 Using Conforming Crests with Poser 6 Using Conforming Crests with DAZ Studio 8 Field Guide List of Species 9 Baltimore Oriole 10 Brown Creeper 11 Curve-billed Thrasher 12 Greater Roadrunner 13 ’I’iwi 14 Oak Titmouse 15 ‘Omao 17 Red-breasted Nuthatch 18 Red Crossbill 19 Spotted Towhee 20 Western Meadowlark 21 Western Scrub-Jay 22 Western Tanager 23 White-crowned Sparrow 24 Resources, Credits and Thanks 25 Opinions expressed on this booklet are solely that of the author, Ken Gilliland, and may or may not reflect the opinions of the publisher, DAZ 3D. 2 Songbird ReMix Cool & Unusual Manual & Field Guide Copyrighted 2006-2011 by Ken Gilliland SongbirdReMix.com Introduction Songbird ReMix 'Cool and Unusual' Birds is an eclectic collection of birds from North America and the Hawaiian Islands. 'Cool and Unusual' Birds adds many new colorful and specialized bird species such as the Red Crossbill, whose specialized beak that allow the collection of pine nuts from pine cones, or the Brown Creeper who can camouflage itself into a piece of bark and the Roadrunner who spends more time on foot than on wing. Colorful exotics are also included like the crimson red 'I'iwi, a Hawaiian honeycreeper whose curved beak is a specialized for feeding on Hawaiian orchids, the Orange and Black Baltimore Oriole, who has more interest in fruit orchards than baseball diamonds and the lemon yellow songster, the western meadowlark who could be coming soon to a field fence post in your imagery. -

Trip Report June 21 – July 2, 2017 | Written by Guide Gerard Gorman

Austria & Hungary: Trip Report June 21 – July 2, 2017 | Written by guide Gerard Gorman With Guide Gerard Gorman and Participants: Jane, Susan, and Cynthia and David This was the first Naturalist Journeys tour to combine Austria and Hungary, and it was a great success. We visited and birded some wonderfully diverse habitats and landscapes in 12 days — the forested foothills of the Alps in Lower Austria, the higher Alpine peak of Hochkar, the reed beds around Lake Neusiedler, the grasslands and wetlands of the Seewinkel in Austria and the Hanság in Hungary, the lowland steppes and farmlands of the Kiskunság east of the Danube, and finally the pleasant rolling limestone hills of the Bükk in north-east Hungary. In this way, we encountered diverse and distinct habitats and therefore birds, other wildlife, and flora, everywhere we went. We also stayed in a variety of different family-run guesthouses and lodges and sampled only local cuisine. As we went, we also found time to take in some of the rich history and culture of these two countries. Wed., June 21, 2017 We met up at Vienna International Airport at noon and were quickly on our way eastwards into Lower Austria. It was a pleasant sunny day and the traffic around the city was a little heavy, but we were soon away from the ring-road and in rural Austria. Roadside birds included both Carrion and Hooded Crows, several Eurasian Kestrels, and Barn Swallows zoomed overhead. Near Hainfeld we drove up a farm road, stopped for a picnic, and did our first real birding. -

Hungary & the Czech Republic

HUNGARY & THE CZECH REPUBLIC: BIRDS & MUSIC FROM BUDAPEST TO PRAGUE SEPTEMBER 8–23, 2018 Great Bustard © Balázs Szigeti LEADER: BALÁZS SZIGETI LIST COMPILED BY: BALÁZS SZIGETI VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM HUNGARY & THE CZECH REPUBLIC: BIRDS & MUSIC FROM BUDAPEST TO PRAGUE SEPTEMBER 8–23, 2018 By Balázs Szigeti September 9, Day 2 The tour started with some of the participants arriving well ahead of schedule. We used the extra time for shopping for supplies before returning to the airport to greet another arriving couple. All together we headed straight to our hotel at the edge of the small town of Bugyi. We checked into our rooms, sorted out the safe and other details, and proceeded to have lunch in the hotel restaurant. With some of the group present, we decided to use the rest of the afternoon to explore some of the nearby birding areas, which proved very productive. The area of Apaj Puszta with its marshes, fish farming ponds, and reedbeds held plenty of birds. Highlights included a Black Woodpecker perched on the top of a bare branch giving excellent views. We saw Purple Heron and a rather close Ferruginous Duck in a little channel. Huge flocks of Graylag Geese fed in the marshes along with Eurasian Spoonbills; Great and Little egrets were present as well and often were disturbed by the presence of several White-tailed Eagles in the area whose European Turtle-Dove © Balazs Szigeti appearance often put hundreds of birds into flight. A late migrant European Turtle-Dove was also posing well. -

The Birds and Other Wildlife Recorded on the David Bishop Bird Tours Bhutan Tour - 2015

The Birds and Other Wildlife recorded on the David Bishop Bird Tours Bhutan Tour - 2015 Wallcreeper © K. David Bishop Compiled and led by K. David Bishop David Bishop Bird Tours Bhutan 2015 BHUTAN 2015 “The Paro Dzong (monastery), guarded by icy crags, sits warming under the late afternoon sun. It seems to welcome our approach to our beautifully located hotel. An Ibisbill, so subtle as to be taken for a glacial stone, dips quietly in the snowmelt. This is indeed the Kingdom of Bhutan and the land of the peaceful Dragon.” As my good friend Steve Hilty remarked on first setting foot in the kingdom, "This is fairytale land." K. David Bishop This was my 28th bird tour to Bhutan. I first began leading bird tours to this magical kingdom in 1994 and have enjoyed the privilege of returning there once or twice a year almost annually since then. So what is it that has makes this particular tour so attractive? Quite simply Bhutan is in a class of its very own. Yes it is an expensive tour (although with David Bishop Bird Tours perhaps not so), largely because the Bhutanese have decided (in our opinion quite rightly) that they would rather not compromise their culture and spectacular natural environment to hundreds of thousands of tourists and in consequence they charge a princely sum for being among the privileged few to visit their country. Similarly we feel that we have a very special product to offer and whilst we could make it shorter and thus less expensive we feel that that would diminish the experience. -

Austria and Hungary Birding Adventure

1 | ITINERARY Austria and Hungary Birding Adventure AUSTRIA AND HUNGARY BIRDING ADVENTURE 12 – 23 MAY 2021 Eurasian Bittern will hopefully be found on this trip. 2 | ITINERARY Austria and Hungary Birding Adventure This tour takes us through two great birding destinations at the heart of Europe, Austria and Hungary. The itinerary comprises uplands in Austria in the Alps and lowlands in the Hungarian plains. Our route takes us through many key Central European habitats and will allow us to observe a large number of bird species of this area, which include many species that rarely occur in the west of Europe. These include Pygmy Cormorant, Ferruginous Duck, Saker Falcon, Eastern Imperial Eagle, Syrian and White-backed Woodpeckers (among ten woodpecker species, for which, with luck, we have a fair chance to see them all), and River and Barred Warblers. Around 200 bird species can be expected. White-backed Woodpecker is one of the ten species of woodpeckers we may see on this tour. In addition, both countries have rich histories, with some impressive architecture, which will be apparent as we travel through and explore them. We will spend the nights in smaller guest houses in the best birding locations, rather than in big hotels in towns. All rooms are en-suite and the cuisine and wines are local. Itinerary (12 days/11 nights) Day 1. Arrival in Vienna, two-hour transfer to the Lower Alps (Austria) We will meet at the Vienna International Airport at noon and then depart south-westward for the forested mountains of Niederösterreich (Lower Austria), a journey of less than two hours. -

Status of the Brown Creeper (Certhia Americana) in Alberta

Status of the Brown Creeper (Certhia americana) in Alberta Alberta Wildlife Status Report No. 49 Status of the Brown Creeper (Certhia americana) in Alberta Prepared for: Alberta Sustainable Resource Development (SRD) Alberta Conservation Association (ACA) Prepared by: Kevin Hannah This report has been reviewed, revised, and edited prior to publication. It is an SRD/ACA working document that will be revised and updated periodically. Alberta Wildlife Status Report No. 49 June 2003 Published By: i Publication No. T/047 ISBN: 0-7785-2917-7 (Printed Edition) ISBN: 0-7785-2918-5 (On-line Edition) ISSN: 1206-4912 (Printed Edition) ISSN: 1499-4682 (On-line Edition) Series Editors: Sue Peters and Robin Gutsell Illustrations: Brian Huffman For copies of this report,visit our web site at : http://www3.gov.ab.ca/srd/fw/riskspecies/ and click on “Detailed Status” OR Contact: Information Centre - Publications Alberta Environment/Alberta Sustainable Resource Development Fish and Wildlife Division Main Floor, Great West Life Building 9920 - 108 Street Edmonton, Alberta, Canada T5K 2M4 Telephone: (780) 422-2079 OR Information Service Alberta Environment/Alberta Sustainable Resource Development #100, 3115 - 12 Street NE Calgary, Alberta, Canada T2E 7J2 Telephone: (403) 297-6424 This publication may be cited as: Alberta Sustainable Resource Development. 2003. Status of the Brown Creeper (Certhia americana) in Alberta. Alberta Sustainable Resource Development, Fish and Wildlife Division, and Alberta Conservation Association, Wildlife Status Report No. 49, Edmonton, AB. 30 pp. ii PREFACE Every five years, the Fish and Wildlife Division of Alberta Sustainable Resource Development reviews the status of wildlife species in Alberta. These overviews, which have been conducted in 1991, 1996 and 2000, assign individual species “ranks” that reflect the perceived level of risk to populations that occur in the province.