Little White Salmon Valley Memories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Columbia River Basin, Columbia Gorge Province Carson, Spring Creek, Little White Salmon, and Willard National Fish Hatcheries As

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service - Pacific Region Columbia River Basin Hatchery Review Team Columbia River Basin, Columbia Gorge Province Little White Salmon, Big White Salmon, and Wind River Watersheds Carson, Spring Creek, Little White Salmon, and Willard National Fish Hatcheries Assessments and Recommendations Final Report, Appendix B: Briefing Document; Summary of Background Information December 2007 USFWS Columbia Basin Hatchery Review Team Columbia Gorge NFHs Assessments and Recommendations Report – December 2007 Carson NFH Willard NFH Spring Creek NFH Little White Salmon NFH Figure 1. National Fish Hatcheries in the Columbia River Gorge1 1 Modified figure from Rawding 2000b. USFWS Columbia Basin Hatchery Review Team Columbia Gorge NFHs Assessments and Recommendations Report – December 2007 Table of Contents I. COLUMBIA GORGE REGION ............................................................................................. 1 II. CARSON NATIONAL FISH HATCHERY .......................................................................... 51 IIA. CARSON NFH SPRING CHINOOK ....................................................................... 59 III. SPRING CREEK NATIONAL FISH HATCHERY .............................................................. 95 IIIA. SPRING CREEK NFH TULE FALL CHINOOK ..................................................... 104 IV. LITTLE WHITE SALMON NATIONAL FISH HATCHERY ............................................. 137 IVA. LITTLE WHITE SALMON NFH UPRIVER BRIGHT FALL CHINOOK .................... 147 IVB. LITTLE -

Jim Crow at the Beach: an Oral and Archival History of the Segregated Past at Homestead Bayfront Park

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Biscayne National Park Jim Crow at the Beach: An Oral and Archival History of the Segregated Past at Homestead Bayfront Park. ON THE COVER Biscayne National Park’s Visitor Center harbor, former site of the “Black Beach” at the once-segregated Homestead Bayfront Park. Photo by Biscayne National Park Jim Crow at the Beach: An Oral and Archival History of the Segregated Past at Homestead Bayfront Park. BISC Acc. 413. Iyshia Lowman, University of South Florida National Park Service Biscayne National Park 9700 SW 328th St. Homestead, FL 33033 December, 2012 U.S. Department of the InteriorNational Park Service Biscayne National Park Homestead, FL Contents Figures............................................................................................................................................ iii Acknowledgments.......................................................................................................................... iv Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 A Period in Time ............................................................................................................................. 1 The Long Road to Segregation ....................................................................................................... 4 At the Swimming Hole .................................................................................................................. -

Gifford Pinchot

THE FORGOTTEN FOREST: EXPLORING THE GIFFORD PINCHOT A Publication of the Washington Trails Association1 7A 9 4 8 3 1 10 7C 2 6 5 7B Cover Photo by Ira Spring 2 Table of Contents About Washington Trails Association Page 4 A Million Acres of outdoor Recreation Page 5 Before You Hit the Trail Page 6 Leave No Trace 101 Page 7 The Outings (see map on facing page) 1. Climbing Mount Adams Pages 8-9 2. Cross Country Skiing: Oldman Pass Pages 10-11 3. Horseback Riding: Quartz Creek Pages 12-13 4. Hiking: Juniper Ridge Pages 14-15 5. Backpacking the Pacific Crest Trail: Indian Heaven Wilderness Pages 16-17 6. Mountain Biking: Siouxon Trail Pages 18-19 7. Wildlife Observation: Pages 20-21 A. Goat Rocks Wilderness B. Trapper Creek Wilderness C. Lone Butte Wildlife Emphasis Area 8. Camping at Takhlakh Lake Pages 22-23 9. Fly Fishing the Cowlitz River Pages 24-25 10. Berry Picking in the Sawtooth Berry Fields Pages 26-27 Acknowledgements Page 28 How to Join WTA Page 29-30 Volunteer Trail Maintenance Page 31 Important Contacts Page 32 3 About Washington Trails Association Washington Trails Association (WTA) is the voice for hikers in Washington state. We advocate protection of hiking trails, take volunteers out to maintain them, and promote hiking as a healthy, fun way to explore Washington. Ira Spring and Louise Marshall co-founded WTA in 1966 as a response to the lack of a political voice for Washington’s hiking community. WTA is now the largest state-based hiker advocacy organization in the country, with over 5,500 members and more than 1,800 volunteers. -

Summary of Public Comment, Appendix B

Summary of Public Comment on Roadless Area Conservation Appendix B Requests for Inclusion or Exemption of Specific Areas Table B-1. Requested Inclusions Under the Proposed Rulemaking. Region 1 Northern NATIONAL FOREST OR AREA STATE GRASSLAND The state of Idaho Multiple ID (Individual, Boise, ID - #6033.10200) Roadless areas in Idaho Multiple ID (Individual, Olga, WA - #16638.10110) Inventoried and uninventoried roadless areas (including those Multiple ID, MT encompassed in the Northern Rockies Ecosystem Protection Act) (Individual, Bemidji, MN - #7964.64351) Roadless areas in Montana Multiple MT (Individual, Olga, WA - #16638.10110) Pioneer Scenic Byway in southwest Montana Beaverhead MT (Individual, Butte, MT - #50515.64351) West Big Hole area Beaverhead MT (Individual, Minneapolis, MN - #2892.83000) Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness, along the Selway River, and the Beaverhead-Deerlodge, MT Anaconda-Pintler Wilderness, at Johnson lake, the Pioneer Bitterroot Mountains in the Beaverhead-Deerlodge National Forest and the Great Bear Wilderness (Individual, Missoula, MT - #16940.90200) CLEARWATER NATIONAL FOREST: NORTH FORK Bighorn, Clearwater, Idaho ID, MT, COUNTRY- Panhandle, Lolo WY MALLARD-LARKINS--1300 (also on the Idaho Panhandle National Forest)….encompasses most of the high country between the St. Joe and North Fork Clearwater Rivers….a low elevation section of the North Fork Clearwater….Logging sales (Lower Salmon and Dworshak Blowdown) …a potential wild and scenic river section of the North Fork... THE GREAT BURN--1301 (or Hoodoo also on the Lolo National Forest) … harbors the incomparable Kelly Creek and includes its confluence with Cayuse Creek. This area forms a major headwaters for the North Fork of the Clearwater. …Fish Lake… the Jap, Siam, Goose and Shell Creek drainages WEITAS CREEK--1306 (Bighorn-Weitas)…Weitas Creek…North Fork Clearwater. -

IC-62, Heat Flow Studies in the Steamboat Mountain-Lemei Rock

,. \\ :\ .J ~\ .... 7 \; t,6 i u2 W~~fnffl:RY u.no C ';I, .... DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES i n BERT L. COLE, Commissioner of Public Lands ; RALPH A. BESWICK Supervisor I: s DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES VAUGHN E. LIVINGSTON, JR., State Geologist INFORMATION CIRCULAR 62 HEAT FLOW STUDIES IN THE STEAMBOAT MOUNTAIN-LEMEI ROCK AREA, SKAMANIA COUNTY, WASHINGTON BY J. ERIC SCHUSTER, DAVID D. BLACKWELL, PAUL E. HAMMOND, and MARSHALL T. HUNTTING Final report to the NATIONAL SCIENCE FOUNDATION on sponsored proiect AER75 ... 02747 1978 STATE OF WASHINGTON DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES BERT L COLE, Commissioner of Public Lands RALPH A. BESWICK Supervisor DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES VAUGHN E. LIVINGSTON, JR., State Geologist INFORMATION CIRCULAR WA He<1.t iluw 33.J. -7 stu.diei::,; ln the .M6 t> i Stean, l:on. t --- bJ. ~uu,i ta i u-.Lem~ i 1970 Jiuck d.rea, Skaina11ia Cuunt),, W a i'ii1 i u ~ton HEAT FLOW STUDIES IN THE STEAMBOAT MOUNTAIN-LEMEI ROCK AREA, SKAMANIA COUNTY, WASHINGTON BY J. ERIC SCHUSTER, DAVID D. BLACKWELL, PAUL E. HAMMOND, and MARSHALL T. HUNTTING Final report to the NATIONAL SC !ENCE FOUNDATION on sponsored project AER75-02747 1978 CONTENTS Abstract ................. , . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 1 Introduction ..................................................................... , • . 2 Acknowledgments • • • • • • . • • . • . • • . • . • . • . • . • . • • • • • • . • • • • . • . 3 Geo logy • . • • • • • • . • • • • • • . • • . • • . • . • . • • . • . 4 Genera I features ............................ -

Region Forest Roadless Name GIS Acres 1 Beaverhead-Deerlodge

These acres were calculated from GIS data Available on the Forest Service Roadless website for the 2001 Roadless EIS. The data was downloaded on 8/24/2011 by Suzanne Johnson WO Minerals & Geology‐ GIS/Database Specialist. It was discovered that the Santa Fe NF in NM has errors. This spreadsheet holds the corrected data from the Santa Fe NF. The GIS data was downloaded from the eGIS data center SDE instance on 8/25/2011 Region Forest Roadless Name GIS Acres 1 Beaverhead‐Deerlodge Anderson Mountain 31,500.98 1 Beaverhead‐Deerlodge Basin Creek 9,499.51 1 Beaverhead‐Deerlodge Bear Creek 8,122.88 1 Beaverhead‐Deerlodge Beaver Lake 11,862.81 1 Beaverhead‐Deerlodge Big Horn Mountain 50,845.85 1 Beaverhead‐Deerlodge Black Butte 39,160.06 1 Beaverhead‐Deerlodge Call Mountain 8,795.54 1 Beaverhead‐Deerlodge Cattle Gulch 19,390.45 1 Beaverhead‐Deerlodge Cherry Lakes 19,945.49 1 Beaverhead‐Deerlodge Dixon Mountain 3,674.46 1 Beaverhead‐Deerlodge East Pioneer 145,082.05 1 Beaverhead‐Deerlodge Electric Peak 17,997.26 1 Beaverhead‐Deerlodge Emerine 14,282.26 1 Beaverhead‐Deerlodge Fleecer 31,585.50 1 Beaverhead‐Deerlodge Flint Range / Dolus Lakes 59,213.30 1 Beaverhead‐Deerlodge Four Eyes Canyon 7,029.38 1 Beaverhead‐Deerlodge Fred Burr 5,814.01 1 Beaverhead‐Deerlodge Freezeout Mountain 97,304.68 1 Beaverhead‐Deerlodge Garfield Mountain 41,891.22 1 Beaverhead‐Deerlodge Goat Mountain 9,347.87 1 Beaverhead‐Deerlodge Granulated Mountain 14,950.11 1 Beaverhead‐Deerlodge Highlands 20,043.87 1 Beaverhead‐Deerlodge Italian Peak 90,401.31 1 Beaverhead‐Deerlodge Lone Butte 13,725.16 1 Beaverhead‐Deerlodge Mckenzie Canyon 33,350.48 1 Beaverhead‐Deerlodge Middle Mtn. -

Fall 2017 Main Stage Pitch DIRECTED BY: Zach Schiffman MUSICALLY DIRECTED BY: Jessie Rosso CHOREOGRAPHED BY

BU ON BROADWAY: Fall 2017 Main Stage Pitch DIRECTED BY: Zach Schiffman MUSICALLY DIRECTED BY: Jessie Rosso CHOREOGRAPHED BY: Emma Howard MUSIC: Duncan Sheik BOOK: Steven Slater BASED ON: Spring Awakening Rights available through MTI by Frank Wedekind 1 INTRODUCTION ZACH SCHIFFMAN - DIRECTOR Zach is a rising senior in the College of Communications, majoring in Film & Television major concentrating in writing and producing for television. He is also minoring in Spanish in the College of Arts and Sciences. He will be returning this fall from a semester abroad in Madrid. He has been a part of over 40 shows since the age of eight and has performed on the stage of multiple professional theaters in the Chicago area, such as the Northlight Theatre and the Goodman Theatre. He also has extensive training in theatre including Laban movement, Stanislavsky methods, Chekhov techniques, and more. Directing has been a passion of his since the beginning of his high school career. He has taken courses on directing, studying the methods of William Ball and Richard Brestoff, and engaged in a summer intensive for new directors at the Actors Training Center in Wilmette, IL. In high school, he independently directed two short plays and also assistant directed both a student-written musical and August: Osage County In the summer of 2014, he faced his biggest theatrical challenge to date: co-founding a theatre company while simultaneously directing its inaugural production. The show was the Pulitzer Prize- winning play Proof by David Auburn. The Unit 14 Theatre Company was established with no support from his high school or other adults in the area. -

Grapevine Newsletter for Winter 2003

The Oregon Property Tax System Grapevine Fall 2002/Winter 2003 volume 8, issue 1 Feature Focus Dave Jacobs—Friend and Mentor GRAPEVINE BY AL GAINES GOES “Do you know Dave Jacobs?” Pam ELECTRONIC! Grant, Benton County Assessor, BY SALLY MOORE asked me early in 1999. & CHRISTIE WILSON “No, I don’t think so,” I replied. The next issue of “Well, Dave’s our department field Grapevine will be rep. You’re going to like him.” available to all subscribers in “Really?” I thought to myself. electronic format. I’d just begun working with the We are very excited Benton County staff at that time. But, about this new me- I’d spent eight of the prior ten years dium for keeping you updated working with the Linn County about issues relating to prop- Assessor’s office. And, frankly, I erty tax in Oregon. In addition hadn’t yet met a DOR field rep I’d to our regular schedule (Fall/ have spoken so highly of so quickly Winter and Spring/Summer and sincerely. issues), we will have the ability Dave Jacobs to provide late-breaking news In fact, I’m sure I had a heart attack Hired 1974, Retired 2002 bulletins for hot topics instead one time in the mid-90s when told of having to wait until the next Ray Moon and Tom Clemens were I remember our first meeting well, issue, when the topic is possi- coming to “audit” my commercial because we ended up having lunch bly too late to share. appraisal procedures! You know, that day at the local Chinese restau- pain in the…. -

October Web.Pdf

WHAT’S HAPPENING. Outdoor School | 5 Geology Fieldtrip | 8 Fall Sports Photos | 12 Girls’ Soccer | 16 Flying Carp | 20 Incident at the Holiday Inn | 21 A World of Hunger | 22 Animal Testing | 23 PHOTO FEATURE 12 Military Families | 24 TL Fall Sports Student Artwork | 26 5 8 Exchange Students | 30 On the Cover: Sophomore Alex King pushes past a Horizon Christian defender in Trout Lake’s 3-1 victory over the Eagles early in the season. 26 2 | October, 2010. .WHAT’S HAPPENING. Principal’s Corner Village Voice Staff “Where there is an open mind there will always be a frontier.” ~ Charles Kettering Hope you are having a great fall season. Like the beginning of any year, there is a good deal of positive energy and activity as well as some great challenges. The year has begun with an excellent group of 205 students. This number represents the highest number of students in my 23 years with the school district and a 12% increase in students from last year. In all, counting our new kindergarten students, we have 45 new students in our school this year. Most of this growth is at the K-4 level. Three years ago Trout Lake K-4 student population was about 47 students. We started the 2010-2011 school year with 82 K-4 students. As you might expect this has created some challenges. To meet this challenge we have added some additional teachers to the existing K-4 staff. In addition, we have added some support staff through the Northwest Service Academy Americorp program. -

3Dpageflip Ebook Maker Page 1 of 129 INTRODUCTION

3DPageFlip eBook Maker Page 1 of 129 INTRODUCTION After years of pondering over how awesome it would be to release a compilation of bands from all around the world, we have finally gone and done just that! We asked bands to submit a song and bio for this huge compilation and the response was fantastic. This free e-book is our way of saying thanks to the readers of Heavy Planet and a terrific way to promote some amazing bands spanning the Stoner Rock, Doom, Psychedelic and Sludge Metal genres. Many thanks goes out to all of the bands and labels for allowing us to use their music and most of all to you the readers for making Heavy Planet what it has become today. Cheers! Enjoy and Doom on! ~Reg 3DPageFlip eBook Maker Page 2 of 129 THE ALBUM TITLE I asked my talented group of writers to come up with a name for the compilation and a bunch of different titles were thrown around but one truly encapsulated what Heavy Planet is about. Misha suggested..."Bong Hits From the Astral Basement", we all agreed and here it is, sixty-one of the finest bands from all around the world. Following are the biographies of each band and the artist that contributed the killer artwork. 3DPageFlip eBook Maker Page 3 of 129 THE BANDS 1000MODS 1000mods is a psychedelic/stoner rock band from Chiliomodi, Greece. They were formed in the summer of 2006 and since then, they have played over 100 live shows, including openings for Brant Bjork, Colour Haze, Karma to Burn, My Sleeping Karma, Radio Moscow and many others. -

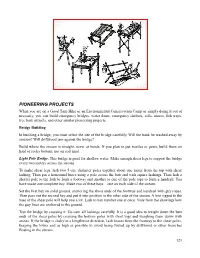

Pioneering Projects

PIONEERING PROJECTS When you are on a Good Turn Hike or an Environmental Conservation Camp or simply doing it out of necessity, you can build emergency bridges, water dams, emergency shelters, rafts, snares, fish traps, tree bark utensils, and other similar pioneering projects. Bridge Building In building a bridge, you must select the site of the bridge carefully. Will the bank be washed away by erosion? Will driftwood jam against the bridge? Build where the stream is straight, never at bends. If you plan to put trestles or posts, build them on hard or rocky bottom, not on soft mud. Light Pole Bridge. This bridge is good for shallow water. Make enough shear legs to support the bridge every two meters across the stream. To make shear legs, lash two 5-cm. diameter poles together about one meter from the top with shear lashing. Then put a horizontal brace using a pole across the butt end with square lashings. Then lash a shorter pole to the fork to form a footway and another to one of the pole tops to form a handrail. You have made one complete bay. Make two of these bays – one on each side of the stream. Set the first bay on solid ground, anchoring the shore ends of the footway and handrail with guy ropes. Then pass out the second bay and put it into position in the other side of the stream. A line rigged to the base of the shear pole will help you a lot. Lash to bay number one at once. -

Website Press Release

The Blue Dolphins - Come On! -- PRESS RELEASE On September 18, 2015, Los Angeles, CA-based eclectic, melodic pop-rock duo The Blue Dolphins will follow up this year's six-song Walking in the Sun EP with their sophomore full-length, Come On!, a fourteen track collection of California-sun soaked roots songs that travel the landscape of memorable melodies, intricate guitar solos, luscious vocal harmonies, and uplifting lyrics, all wrapped up in fantastic production. Comprised of two-time Grammy Award winner engineer Alfonso Rodenas on guitar and Victoria Scott on lead vocals, the duo released the Walking in the Sun EP in May, a prelude to the forthcoming full-length; Walking in the Sun contains six songs Come On!. Prior releases include their debut full-length, 2012's My Favorite Word Is Todayand 2013's In Between EP. Come On! is a major push forward for The Blue Dolphins, reaching towards a more complex and fully produced music scenario, where sonic aesthetics and songwriting are richer and more varied, departing from the pared-down premises and acoustic songs that characterized My Favorite Word Is Today. Come On! embraces folk, pop, and roots-rock with the duo's characteristic optimism and charm. Victoria Scott and Alfonso Rodenas fatefully met at the legendary rock pit The Cat Club on the Sunset Strip in Los Angeles and soon started playing and recording together. Formed in 2010, The Blue Dolphins released their debut full-length and gigged constantly over the following two years in California and Western Europe - earning them a dedicated fan base in the U.S., U.K., and Spain.