Acta Kor Ana Vol. 14, No. 1, June 2011: 313–352 Book

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yun Mi Hwang Phd Thesis

SOUTH KOREAN HISTORICAL DRAMA: GENDER, NATION AND THE HERITAGE INDUSTRY Yun Mi Hwang A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2011 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/1924 This item is protected by original copyright This item is licensed under a Creative Commons Licence SOUTH KOREAN HISTORICAL DRAMA: GENDER, NATION AND THE HERITAGE INDUSTRY YUN MI HWANG Thesis Submitted to the University of St Andrews for the Degree of PhD in Film Studies 2011 DECLARATIONS I, Yun Mi Hwang, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 80,000 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student and as a candidate for the degree of PhD in September 2006; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2006 and 2010. I, Yun Mi Hwang, received assistance in the writing of this thesis in respect of language and grammar, which was provided by R.A.M Wright. Date …17 May 2011.… signature of candidate ……………… I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of PhD in the University of St Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. -

Cultural Production in Transnational Culture: an Analysis of Cultural Creators in the Korean Wave

International Journal of Communication 15(2021), 1810–1835 1932–8036/20210005 Cultural Production in Transnational Culture: An Analysis of Cultural Creators in the Korean Wave DAL YONG JIN1 Simon Fraser University, Canada By employing cultural production approaches in conjunction with the global cultural economy, this article attempts to determine the primary characteristics of the rapid growth of local cultural industries and the global penetration of Korean cultural content. It documents major creators and their products that are received in many countries to identify who they are and what the major cultural products are. It also investigates power relations between cultural creators and the surrounding sociocultural and political milieu, discussing how cultural creators develop local popular culture toward the global cultural markets. I found that cultural creators emphasize the importance of cultural identity to appeal to global audiences as well as local audiences instead of emphasizing solely hybridization. Keywords: cultural production, Hallyu, cultural creators, transnational culture Since the early 2010s, the Korean Wave (Hallyu in Korean) has become globally popular, and media scholars (Han, 2017; T. J. Yoon & Kang, 2017) have paid attention to the recent growth of Hallyu in many parts of the world. Although the influence of Western culture has continued in the Korean cultural market as well as elsewhere, local cultural industries have expanded the exportation of their popular culture to several regions in both the Global South and the Global North. Social media have especially played a major role in disseminating Korean culture (Huang, 2017; Jin & Yoon, 2016), and Korean popular culture is arguably reaching almost every corner of the world. -

Goldsmiths College University of London Locating Contemporary

Goldsmiths College University of London Locating Contemporary South Korean Cinema: Between the Universal and the Particular Seung Woo Ha A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy to the department of Media and Communications January 2013 1 DECLARATION I, Seung Woo Ha confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signed……………………….. Date…..…10-Jan-2013……… 2 ABSTRACT The thesis analyses contemporary South Korean films from the late 1980s up to the present day. It asks whether Korean films have produced a new cinema, by critically examining the criteria by which Korean films are said to be new. Have Korean films really changed aesthetically? What are the limitations, and even pitfalls in contemporary Korean film aesthetics? If there appears to be a true radicalism in Korean films, under which conditions does it emerge? Which films convey its core features? To answer these questions, the study attempts to posit a universalising theory rather than making particular claims about Korean films. Where many other scholars have focused on the historical context of the film texts’ production and their reception, this thesis privileges the film texts themselves, by suggesting that whether those films are new or not will depend on a film text’s individual mode of address. To explore this problem further, this study draws on the concept of ‘concrete universality’ from a Lacanian/Žižekian standpoint. For my purpose, it refers to examining how a kind of disruptive element in a film text’s formal structure obtrudes into the diegetic reality, thus revealing a cinematic ‘distortion’ in the smooth running of reality. -

1997 Conference Program Book (Hangul)

W ELCOME Korea Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages 대한영어교육학회 1997 National Conference and Publishers Exposition Technology in Education; Communicating Beyond Traditional networks October 3-5, 1997 Kyoung-ju Education and Cultural Center Kyoung-ju, South Korea Conference Co-chairs; Demetra Gates Taegu University of Education Kari Kugler Keimyung Junior University, Taegu 1996-97 KOTESOL President; Park Joo-kyung Honam University, Kwangju 1997-98 KOTESOL President Carl Dusthimer Hannam University, Taejon Presentation Selection Committee: Carl Dusthimer, Student Coordination: Steve Garrigues Demetra Gates, Kari Kugler, Jack Large Registration: Rodney Gillett, AeKyoung Large, Jack Program: Robert Dickey, Greg Wilson Large, Lynn Gregory, Betsy Buck Cover: Everette Busbee International Affairs: Carl Dusthimer, Kim Jeong- ryeol, Park Joo Kyung, Mary Wallace Publicity: Oryang Kwon Managing Information Systems: AeKyoung Large, Presiders: Kirsten Reitan Jack Large, Marc Gautron, John Phillips, Thomas Special Events: Hee-Bon Park Duvernay, Kim Jeong-ryeol, Sung Yong Gu, Ryu Seung Hee, The Kyoung-ju Board Of Education W ELCOME DEAR KOTESOL MEMBERS, SPEAKERS, AND FRIENDS: s the 1997 Conference Co-Chairs we would like to welcome you to this year's conference, "Technology Ain Education: Communicating Beyond Traditional Networks." While Korea TESOL is one of the youngest TESOL affiliates in this region of the world, our goal was to give you one of the finest opportunities for professional development available in Korea. The 1997 conference has taken a significant step in this direction. The progress we have made in this direction is based on the foundation developed by the coachers of the past: our incoming President Carl Dusthimer, Professor Woo Sang-do, and Andy Kim. -

Secret Sunshine/ Milyang (2007) “Are You Looking? Do You See?” Major

Secret Sunshine/ Milyang (2007) “Are you looking? Do you see?” Major Credits: Director: Chang-dong Lee Writer: Chang-dong Lee, from a novel by Chong-jung Yi Cinematography: Yong-kyo Cho Cast: Do-yeon Jeon (Shin-ae/ Mrs. Lee), Kang-ho Song (Jong Chan/ Mr. Kim) Production Context: Chang-dong Lee (b. 1954) was a successful novelist before turning to the cinema in 1992, when he became part of the Korean New Wave that includes Kim Ki-duk (Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter… and Spring), Bong Joon-ho (Memories of Murder), and Hong Sang-soo (Hill of Freedom). Lee was drawn to filmmaking following a political shift in Korea away from socialism around the time of the 1988 Seoul Olympics. For Lee, the cinema replaced literature as a means of conveying his social concerns, as becomes clear in his second feature, Peppermint Candy (1999). In contrast to the striking flashback narrative structure of that film and the socially marginalized protagonists of Oasis (2002), Secret Sunshine was designed with “normality” (Lee’s term) in mind. Both lead actors were well known to Korean audiences. Kang-ho Song’s role as Mr. Kim marks a departure from type, since he was best known for gangster and detective roles (most notably in Joon-ho Bong’s excellent Memories of Murder, 2003). Do-yeon Jeon, who won the acting prize at Cannes for her portrayal of Shin-ae, reportedly “hated” the director during their time together shooting the film. Cinematic Aspects: 1. Long Take: Lee deploys these unedited shots at key moments in the narrative (Interestingly, the director has testified that he had decided not to use long takes to preserve the film’s “normality”). -

An Autoethnography on Teaching Undergraduate Korean Studies, on and Off the Peninsula

No Frame to Fit It All: An Autoethnography on Teaching Undergraduate Korean Studies, on and off the Peninsula Cedarbough T. Saeji Acta Koreana, Volume 21, Number 2, December 2018, pp. 443-459 (Article) Published by Keimyung University, Academia Koreana For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/756425 [ Access provided at 1 Oct 2021 21:59 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] ACTA KOREANA Vol. 21, No. 2, December 2018: 443–460 doi:10.18399/acta.2018.21.2.004 No Frame to Fit It All: An Autoethnography on Teaching Undergraduate Korean Studies, on and off the Peninsula CEDARBOUGH T. SAEJI In the past two decades, Korean Studies has expanded to become an interdisciplinary and increasingly international field of study and research. While new undergraduate Korean Studies programs are opening at universities in the Republic of Korea (ROK) and intensifying multi-lateral knowledge transfers, this process also reveals the lack of a clear identity that continues to haunt the field. In this autoethnographic essay, I examine the possibilities and limitations of framing Korea as an object of study for diverse student audiences, looking towards potential futures for the field. I focus on 1) the struggle to escape the nation-state boundaries implied in the habitual terminology, particularly when teaching in the ROK, where the country is unmarked (“Han’guk”), the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea is marked (“Pukhan”), and the diaspora is rarely mentioned at all; 2) the implications of the expansion of Korean Studies as a major within the ROK; 3) in-class navigations of Korean national pride, the trap of Korean uniqueness and (self-)orientalization and CEDARBOUGH T. -

South Korean Cinema and the Conditions of Capitalist Individuation

The Intimacy of Distance: South Korean Cinema and the Conditions of Capitalist Individuation By Jisung Catherine Kim A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Kristen Whissel, Chair Professor Mark Sandberg Professor Elaine Kim Fall 2013 The Intimacy of Distance: South Korean Cinema and the Conditions of Capitalist Individuation © 2013 by Jisung Catherine Kim Abstract The Intimacy of Distance: South Korean Cinema and the Conditions of Capitalist Individuation by Jisung Catherine Kim Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media University of California, Berkeley Professor Kristen Whissel, Chair In The Intimacy of Distance, I reconceive the historical experience of capitalism’s globalization through the vantage point of South Korean cinema. According to world leaders’ discursive construction of South Korea, South Korea is a site of “progress” that proves the superiority of the free market capitalist system for “developing” the so-called “Third World.” Challenging this contention, my dissertation demonstrates how recent South Korean cinema made between 1998 and the first decade of the twenty-first century rearticulates South Korea as a site of economic disaster, ongoing historical trauma and what I call impassible “transmodernity” (compulsory capitalist restructuring alongside, and in conflict with, deep-seated tradition). Made during the first years after the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis and the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, the films under consideration here visualize the various dystopian social and economic changes attendant upon epidemic capitalist restructuring: social alienation, familial fragmentation, and widening economic division. -

"Militarized Masculinity" and the Conscientious Objector Movement

Volume 7 | Issue 12 | Number 1 | Article ID 3087 | Mar 16, 2009 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus Militarism and Anti-militarism in South Korea: "Militarized Masculinity" and the Conscientious Objector Movement. Vladimir Tikhonov Militarism and Anti-militarism in South Korea: include revolutionary and post-revolutionary “Militarized Masculinity” and the Conscientious France (which began the history of modern Objector Movement. conscription by declaring the levée en masse on August 23, 1793), and the Prussian state, Vladimir Tikhonov (Pak Noja) which began introducing French-style conscription practices after suffering a defeat Korea – "a national defense/conscription state" at the hands of Napoleon’s conscript army in 1806-1807.3 In more recent times, the state of It is a well-known fact that warfare and Israel successfully used a comprehensive obligatory military service system long played conscription system applicable to both men and decisive role in the formation of modern nation- women. The conscription system inculcated states, first in Europe and later elsewhere in Zionist ideals and the newly-forged Israeli the world. While externally the military national identity, as well as a siege mentality prowess of a given state was (and still is) based upon the imperative of the “national decisive for defining its place in a competitive defense” against the demonized Arabic/Muslim international system explicitly based upon an world, into the minds of a very heterogeneous equilibrium of military force and hegemonic 4 1 body of citizens, -

Guide for International Faculty (Fall 2021) Table of Contents

F Guide for International Faculty (Fall 2021) Table of Contents Ⅰ. General Information 1. Brief History .................................................................................... 1 2. Chronology .................................................................................... 2 3. Organizational Chart ...................................................................... 5 4. Campus Map .................................................................................. 6 5. Mission Statement ........................................................................... 6 6. Facts and Figures ........................................................................... 7 Ⅱ. Organization and Administration 1. University Primary Administrations and Affiliates A. Campus Ministry Team .............................................................. 8 B. Human Rights Center .................................................................. 8 C. Academic Affairs Team .............................................................. 8 D. Faculty Personnel Team .......................................................... 9 E. Center for International Affairs ................................................... 9 F. Center for Teaching & Learning ................................................. 10 G. Center for e-Learning .............................................................. 10 H. Health Care Center .................................................................. 10 I. System Operation Team ............................................................. -

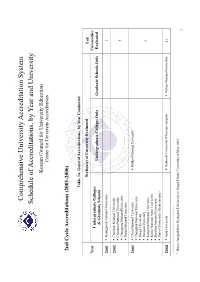

Schedule of Accreditations, by Year and University

Comprehensive University Accreditation System Schedule of Accreditations, by Year and University Korean Council for University Education Center for University Accreditation 2nd Cycle Accreditations (2001-2006) Table 1a: General Accreditations, by Year Conducted Section(s) of University Evaluated # of Year Universities Undergraduate Colleges Undergraduate Colleges Only Graduate Schools Only Evaluated & Graduate Schools 2001 Kyungpook National University 1 2002 Chonbuk National University Chonnam National University 4 Chungnam National University Pusan National University 2003 Cheju National University Mokpo National University Chungbuk National University Daegu University Daejeon University 9 Kangwon National University Korea National Sport University Sunchon National University Yonsei University (Seoul campus) 2004 Ajou University Dankook University (Cheonan campus) Mokpo National University 41 1 Name changed from Kyungsan University to Daegu Haany University in May 2003. 1 Andong National University Hanyang University (Ansan campus) Catholic University of Daegu Yonsei University (Wonju campus) Catholic University of Korea Changwon National University Chosun University Daegu Haany University1 Dankook University (Seoul campus) Dong-A University Dong-eui University Dongseo University Ewha Womans University Gyeongsang National University Hallym University Hanshin University Hansung University Hanyang University Hoseo University Inha University Inje University Jeonju University Konkuk University Korea -

Keimyung University 2

Contents 1. About Republic of Korea and Daegu 03 KEIMYUNG UNIVERSITY 2. About Keimyung University 04 3. Why Keimyung University? 06 4. Student Activities (Programs) 09 5. Faces of Keimyung University 13 OPENING THE LIGHT TO THE WORLD 1095 Dalgubeol-daero, Dalseo-gu, Daegu 42601, Republic of Korea · Undergraduate Program (Except Chinese Students) Tel. +82-53-580-6029 / E-mail. [email protected] · Undergraduate Program (Only Chinese Students) Tel. +82-53-580-6497 / E-mail. [email protected] · Graduate Program Tel. +82-53-580-6254 / E-mail. [email protected] · Korean Language Program Tel. +82-53-580-6353, 6355 / E-mail. [email protected] OPENING THE LIGHT TO THE WORLD_KMU 2 / 3 2 ABOUT REPUBLIC OF KOREA1 AND DAEGU REPUBLIC OF korea DAEGU METROPOLITAN CITY The Republic of Korea which is approximately 5,000 years Daegu is located in the south-east of the Republic of Korea old has overcome a variety of difficulties such as the Korean- and it is the fourth largest city after Seoul, Busan and War, but it has grown economically and is currently ranked Incheon with about 2.5 million residents. Daegu is famous the 11th richest economy in the world. The economy is driven for high quality apples, and its historic textile industry. With by manufacturing and exports including ships, automobiles, the establishment of the Daegu-Gyeongbuk Free Economic mobile phones, PCs, and TVs. Recently, the Korean-Wave has Zone, Daegu is currently focusing on fostering fashion and Seoul also added to the country’s exports through the popularity high-tech industries. -

Lesbians in Japan and South Korea

Her Story: Lesbians in Japan and South Korea Elise Fylling EAST 4590 – Master’s Thesis in East Asian Studies African and Asian Studies 60 credits – spring 2012 Department of Culture Studies and Oriental Languages Faculty of Humanities University of Oslo Her Story: Lesbians in Japan and South Korea Master’s thesis, Elise Fylling © Elise Fylling 2012 Her Story: Lesbians in Japan and South Korea Elise Fylling Academic supervisor: Vladimir Tikhonov http://www.duo.uio.no Printed by: Webergs Printshop Summary Lesbians in Japan and South Korea have long been ignored in both academic, and in social context. The assumption that there are no lesbians in Japan or South Korea dominates a large population in these societies, because lesbians do not identify as such in the public domain. Instead they often live double lives showing one side of themselves to the public and another in private. Although there exist no formal laws against homosexuality, a social barrier in relation to coming out to one’s family, friends or co-workers is highly present. Shame, embarrassment and fear of being rejected as deviant or abnormal makes it difficult to step outside of the bonds put on by society’s hetero-normative structures. What is it like to be lesbian in contemporary Japan and South Korea? In my dissertation I look closely at the Japanese and South Korean society’s attitudes towards young lesbians, examining their experiences concerning identity, invisibility, family relations, the question of marriage and how they see themselves in society. I also touch upon how they meet others in spite of their invisibility as well as giving some insight to the way they chose to live their life.