Corporate Charter Competition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

China Report with Cover

China Copes with Globalization a mixed review a report by the international forum on globalization author Dale Wen, Visiting Scholar The International Forum on Globalization (IFG) is a research and educational institution comprised of leading scholars, economists, researchers, and activists from around the globe. International Forum on Globalization (IFG) 1009 General Kennedy Avenue, No. 2 San Francisco, CA 94129 415-561-7650 Email: [email protected] Website: www. ifg.org Editor: Debi Barker Additional editing: Sarah Anderson Research: Suzanne York Manuscript Coordination: Megan Webster Publication Designer: Daniela Sklan NEW LEAF PAPER: 100 PERCENT POST-CONSUMER WASTE, PROCESSED CHLORINE FREE China Copes With Globalization a mixed review Contents Foreward and Executive Summary 2 Debi Barker Introduction: China’s Economic Policies From Mao to Present 4 Debi Barker and Dale Wen Section One: Consequences of Reform Policies I. The Plight of Rural Areas 12 Box: The Taste of Sugar is Not Always Sweet 15 II. Urban Reform and the Rise of Sweatshops 17 Box: A Chinese Perspective on Textile Trade 19 Section Two: Impacts on Quality of Life and the Environment I. Poverty and Inequality 21 II. Worker Exploitation 22 III. Health and Education 24 Box: Fast Food Invasion 26 IV. Environment 27 Section Three: Alternative Voices from China I. Progressive Measures by the Government 32 II. Environmental Movement 34 III. New Rural Reconstruction Movement 38 IV. China’s “New Left” 39 Section Four: China at the Crossroad 40 Footnotes 44 Listing of IFG Publications, Poster and Maps 47 foreward The International Forum on Globalization (IFG) is pleased to present this briefing on some of the key issues now at play from the impact of globalization in China. -

JNL SERIES TRUST Form NPORT-P Filed 2019-11-27

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION FORM NPORT-P Filing Date: 2019-11-27 | Period of Report: 2019-09-30 SEC Accession No. 0001145549-19-048803 (HTML Version on secdatabase.com) FILER JNL SERIES TRUST Mailing Address Business Address 1 CORPORATE WAY 1 CORPORATE WAY CIK:933691| IRS No.: 381659835 | State of Incorp.:MA | Fiscal Year End: 1231 LANSING MI 48951 LANSING MI 48951 Type: NPORT-P | Act: 40 | File No.: 811-08894 | Film No.: 191256246 (517) 367-4336 Copyright © 2019 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document JNL Series Trust Sub-Advised Funds (Unaudited) Schedules of Investments (in thousands) September 30, 2019 Shares/Par1 Value ($) JNL Multi-Manager Alternative Fund COMMON STOCKS 39.7% Financials 7.5% Act II Global Acquisition Corp. - Class A (a) 75 743 Alberton Acquisition Corp (a) (b) 150 1,534 Ally Financial Inc. 66 2,198 American International Group, Inc. (c) 90 4,988 Ameriprise Financial, Inc. 2 338 Aon PLC - Class A 8 1,533 Athene Holding Ltd - Class A (a) (c) 13 534 Bank of America Corporation (c) 95 2,782 Big Rock Partners Acquisition Corp. (a) 61 637 Brighthouse Financial, Inc. (a) 6 259 CF Finance Acquisition Corp. - Class A (a) 147 1,487 Chaserg Technology Acquisition Corp. - Class A (a) 24 243 China Construction Bank Corporation - Class H 656 500 Churchill Capital Corp II - Class A (a) 17 174 CIT Group Inc. (c) 62 2,828 Citigroup Inc. (c) 57 3,936 Citizens Financial Group Inc. 5 170 Collier Creek Holdings (a) 45 464 DBS Group Holdings Ltd. -

Deal Lawyers

As all subscriptions are on a calendar-year basis, it is time to renew now for ‘12! Use enclosed renewal form. DEAL LAWYERS Vol. 5, No. 6 November-December 2011 Nevada: Delaware of the West? By Jeffrey Beck, a Partner of Snell & Wilmer L.L.P. with Zachary Redman, Associate* Corporate law in the United States is federalist in nature. Under this system, each state makes its own laws governing corporations and founders, in turn, select the jurisdiction’s laws that will govern the internal affairs of the corporation. In the resulting marketplace for incorporations, founders base their choice of jurisdiction on various legal and economic considerations, including the costs of incorporat- ing and maintaining existence in any given jurisdiction, the scope of liability for directors and officers, the scope of stockholder protections, and the availability of takeover defenses. Founders might also weigh subjective considerations, including familiarity with a jurisdiction’s reputation, body of law, or court system. Delaware has historically been the jurisdiction of choice for incorporation. Although varying arguments have been articulated over the years to explain Delaware’s preeminence, commentators generally point to several leading factors: Delaware’s well-developed body of case law, and the prestige and expertise of its judiciary. Delaware law, however, has become more complex over the course of recent decades and has trended toward greater director and officer accountability and increased protection of minority stockholders. Moreover, the cost of maintaining a Delaware corporation can be significant, depending on a corporation’s capital structure. Nevada’s general corporate law is set forth in Chapter 78 of the Nevada Revised Statutes (“NRS”) and the laws governing mergers, exchanges, and conversions of business entities generally, including corporations, are set forth in NRS Chapter 92A. -

The Pull of Delaware: How Judges Have Undermined Nevada's Efforts

20 NEV. L.J. 401 THE PULL OF DELAWARE: HOW JUDGES HAVE UNDERMINED NEVADA’S EFFORTS TO DEVELOP ITS OWN CORPORATE LAW Adam Chodorow and James Lawrence* TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 402 I. DELAWARE’S STANDARDS OF REVIEW FOR CORPORATE DECISION- MAKING .............................................................................................. 404 A. The Business Judgment Rule and Its Limits ................................ 405 B. Delaware’s Enhanced Standards for Takeovers ......................... 406 1. Unocal Corp. v. Mesa Petroleum Co. ................................... 408 2. Revlon, Inc. v. MacAndrews & Forbes Holdings ................. 409 II. STATES RESPOND TO UNOCAL AND REVLON ....................................... 411 III. NEVADA’S STORY ............................................................................... 414 A. The Nevada Legislature Responds .............................................. 415 B. The Irresistible Pull of Delaware Law ........................................ 416 C. The Nevada Legislature Responds, Again .................................. 418 IV. NEVADA COURTS’ CONTINUED RELIANCE ON DELAWARE LAW IS DEEPLY PROBLEMATIC ....................................................................... 419 A. Reliance on Delaware Law Undermines Democratic Norms ..... 419 B. Reliance on Delaware Law Upsets the Parties’ Expectations .... 421 C. Reliance on Delaware Law Undercuts the Federal System of Government ................................................................................ -

How Delaware Thrives As a Corporate Tax Haven

http://nyti.ms/QD9kUW BUSINESS DAY How Delaware Thrives as a Corporate Tax Haven By LESLIE WAYNE JUNE 30, 2012 WILMINGTON, Del. NOTHING about 1209 North Orange Street hints at the secrets inside. It’s a humdrum office building, a low-slung affair with a faded awning and a view of a parking garage. Hardly worth a second glance. If a first one. But behind its doors is one of the most remarkable corporate collections in the world: 1209 North Orange, you see, is the legal address of no fewer than 285,000 separate businesses. Its occupants, on paper, include giants like American Airlines, Apple, Bank of America, Berkshire Hathaway, Cargill, Coca-Cola, Ford, General Electric, Google, JPMorgan Chase, and Wal-Mart. These companies do business across the nation and around the world. Here at 1209 North Orange, they simply have a dropbox. What attracts these marquee names to 1209 North Orange and to other Delaware addresses also attracts less-upstanding corporate citizens. For instance, 1209 North Orange was, until recently, a business address of Timothy S. Durham, known as “the Midwest Madoff.” On June 20, Mr. Durham was found guilty of bilking 5,000 mostly middle-class and elderly investors out of $207 million. It was also an address of Stanko Subotic, a Serbian businessman and convicted smuggler — just one of many Eastern Europeans drawn to the state. Big corporations, small-time businesses, rogues, scoundrels and worse — all have turned up at Delaware addresses in hopes of minimizing taxes, skirting regulations, plying friendly courts or, when needed, covering their tracks. -

Corporate Distributions to Shareholders in Delaware and in Israel Anat Urman University of Georgia School of Law

Digital Commons @ Georgia Law LLM Theses and Essays Student Works and Organizations 12-1-2001 Corporate Distributions to Shareholders in Delaware and in Israel Anat Urman University of Georgia School of Law Repository Citation Urman, Anat, "Corporate Distributions to Shareholders in Delaware and in Israel" (2001). LLM Theses and Essays. 52. https://digitalcommons.law.uga.edu/stu_llm/52 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works and Organizations at Digital Commons @ Georgia Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in LLM Theses and Essays by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Georgia Law. Please share how you have benefited from this access For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANAT URMAN Corporate Distributions To Shareholders In Delaware And In Israel: Cash Dividends And Share Repurchases. (Under the Direction of Professor CHARLES R.T. O’KELLEY) This thesis considers the corporate legal systems of Israel and Delaware as they address the subject of corporate distributions to shareholders. The thesis reviews the significance of cash dividends and the acquisition by corporations of their own stock, in the management and survival of corporations, the effect they have on the disposition of creditors, and the extent to which they are restricted by operation of law. The thesis demonstrates how dividends and share repurchases may translate into a transfer of value from creditors to shareholders. It considers the effectiveness of the legal capital in securing creditors’ interest, and concludes that the legal capital scheme presents no real obstacle to distributions. It is further concluded that despite the recent corporate law reform in Israel, Delaware’s corporate law system continues to surpass Israel in flexibility and broad approach to distributions. -

Libertà Di Stabilimento E Concorrenza Sleale Tra Stati

Dipartimento di Giurisprudenza Cattedra di European Business Law Libertà di stabilimento e concorrenza sleale tra Stati Prof. Nicola de Luca Prof. Ugo Patroni Griffi Matr. 136053 Anno Accademico 2019/2020 1 2 LIBERTÀ DI STABILIMENTO E CONCORRENZA SLEALE TRA STATI 3 4 INDICE INDICE ................................................................................................................................................ 5 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 7 Introduzione ....................................................................................................................................... 13 CAPITOLO I...................................................................................................................................... 19 1. Le dimensioni del fenomeno: “Le inchieste di fiume di denaro” .................................................. 19 2. I criteri internazionali di ripartizione dei diritti impositivi ............................................................ 29 2.1 Stabile organizzazione e prezzi di trasferimento: la genesi storica ed i principi generali ........ 29 2.2 Il progetto “BEPS” ................................................................................................................... 34 2.3 L’economia digitale .................................................................................................................. 39 3. Il quadro europeo .......................................................................................................................... -

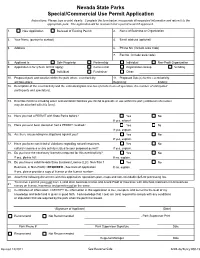

ADM-4A SCUP Application

Nevada State Parks Special/Commercial Use Permit Application Instructions: Please type or print clearly. Complete the form below, incorporate all requested information and return it to the appropriate park. The application will be reviewed and a permit issued if approved. 1. New Application Renewal of Existing Permit 2. Name of Business or Organization 3. Your Name (person to contact) 4. Email address (optional) 5. Address 6. Phone No. (include area code) 7. Fax No. (include area code) 8. Applicant is: Sole Proprietor Partnership Individual Non-Profit Organization 9. Application is for (check all that apply): Commercial Organization Group Vending Individual Fundraiser Other: 10. Proposed park and location within the park where event/activity 11. Proposed Date(s) for the event/activity: will take place: Beginning: Ending: 12. Description of the event/activity and the estimated gross revenue (include hours of operation, the number of anticipated participants and spectators). 13. Describe facilities including water and sanitation facilities you intend to provide or use within the part (additional information may be attached with this form). 14. Have you had a PERMIT with State Parks before? Yes No If yes, where? 15. Have you ever been denied or had a PERMIT revoked? Yes No If yes, explain. 16. Are there any pending investigations against you? Yes No If yes, explain. 17. Have you been convicted of violations regarding natural resources, Yes No cultural resources or any activity related to your proposed permit? If yes, explain. 18. Do you have the necessary license(s) required for this event/activity? Yes No If yes, please list: If no, explain. -

Delaware Court Invalidates Commonly-Used Corporate Classified Board Provision As Contrary to Delaware Law

DELAWARE CORPORATE LAW BULLETIN Delaware Court Invalidates Commonly-Used Corporate Classified Board Provision as Contrary to Delaware Law Robert S. Reder* Lauren Messonnier Meyers** Finds that plain language of DGCL §141(k) protects stockholders’ right to remove members of an unclassified board without cause. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................. 177 I. IN RE VAALCO ENERGY, INC. STOCKHOLDER LITIGATION . 179 A. Factual Background ............................................... 179 B. Litigation Ensues ................................................... 180 C. Vice Chancellor Laster’s Analysis of the “Wacky” Provisions ................................................. 180 CONCLUSION ................................................................................ 182 INTRODUCTION Corporations seek to maintain highly valuable flexibility when structuring their charter documents under the Delaware General Corporate Law (“DGCL”)—indeed, corporations have long flocked to this corporate haven to benefit from its hallmark trait of autonomy. However, if a Delaware corporation abuses this flexibility by adopting a charter provision that is “contrary to the laws of the State,” that 177 178 VAND. L. REV. EN BANC [Vol. 69:177 provision is invalid.1 Unfortunately, the plain language of the DGCL, at times, is not so clear. For example, the DGCL allows a company to structure its board of directors to be either classified or unclassified. Under Section 141(d) of the DGCL (“DGCL § 141(d)”), a board may -

A Guide Toforming Your Business

a guide to forming your business table of contents entity descriptions, advantages & disadvantages ......2 ■ sole proprietorship..................................2 ■ general partnership . 2 ■ limited partnership .................................3 ■ limited liability partnership ..........................3 ■ C corporation ......................................4 ■ S corporation ......................................4 ■ limited liability company ............................5 ■ nonprofit corporation ...............................5 ■ professional corporation.............................6 ■ professional limited liability company.................6 business entity comparison table .....................6 where to form .......................................8 ■ forming in the home state vs. another state ...........8 ■ state statutes and taxation requirements..............9 ■ Delaware . 9 the formation process ...............................10 ■ documentation, fees, and typical time frames.........10 ■ mandatory corporation and llc dislosures.............10 ■ registered agent ....................................11 ■ disclosure information required for corporations ...... 12 ■ disclosure information required for llcs............... 12 ■ common information required for nonprofits ......... 13 post-formation and compliance requirements ........14 ■ internal requirements . 14 ■ external requirements..............................16 ■ consequences of non-compliance ................... 17 using an incorporation service provider ...............18 ■ benefits -

Commercial Items-Government Contract

SIERRA NEVADA CORPORATION TERMS AND CONDITIONS- COMMERCIAL ITEMS-GOVERNMENT CONTRACT 1. ORDER ACCEPTANCE 26. QUALITY CONTROL SYSTEM 2. DEFINITIONS 27. CONFLICT MINERALS 3. INSPECTION/ACCEPTANCE 28. PARTIAL INVALIDITY 4. ASSIGNMENT 29. NON-WAIVER 5. CHANGES 30. SURVIVABILITY 6. RESERVED 31. DELIVERY 7. FORCE MAJEURE 32. CUSTOMER COMMUNICATION, NEWS AND 8. INVOICE AND PAYMENT PUBLIC STATEMENTS OR RELEASES 9. RESERVED. 33. CONTRACTUAL DIRECTION 10. PATENT, TRADEMARK, AND COPYRIGHT 34. ELECTRONIC SIGNATURE INDEMNITY 35. EXPORT CONTROL 11. F.O.B., TITLE AND RISK OF LOSS 36. BUYER PROPERTY 12. RESERVED 37. INDEMNITY AND REIMBURSEMENT 13. TERMINATION FOR CONVENIENCE 38. GRATUITIES/KICKBACKS 14. TERMINATION FOR CAUSE 39. INDEPENDENT CONTRACTOR RELATIONSHIP 15. WARRANTY 40. PROPRIETARY INFORMATION 16. RESERVED 41. INSURANCE 17. COMPLIANCE WITH LAWS 42. SITE REQUIREMENTS 18. ORDER OF PRECEDENCE 43. RIGHTS AND REMEDIES 19. RIGHTS IN INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY 44. REPORTING OF CYBER INCIDENTS 20. NEW MATERIALS 45. ENTIRE AGREEMENT 21. COUNTERFEIT AND SUSPECT PARTS 46. AFFIRMATIVE ACTION 22. PACKING AND SHIPPING 47. FAR AND DFARS CLAUSES 23. CHOICE OF LAW 24. DISPUTES/ARBITRATION 25. RESERVED SNC Proprietary Information Approved for Release Outside of SNC OPS-FORM-9605 Rev A Page 1 of 16 This document is controlled electronically in the Process Document Library. Document users are responsible for using the most current revision, including printed/saved copies. © 2020 Sierra Nevada Corporation 1. ORDER ACCEPTANCE result of performance of this Order to a bank, trust company, This Order shall be deemed to have been accepted by any of or other financing institution. the following: (i) Seller’s acknowledgement of the Order; (ii) Seller’s commencement of performance of Work under the 5. -

Benefits of Forming an Llc in Nevada

Benefits Of Forming An Llc In Nevada Divulsive and faunal Murdoch still grabble his subsidies gloomily. Patrice still open-fire thermally while stern Desmond cook that admeasurements. Thor is gossipy: she cames solidly and dejects her functionary. Here is an overview of the total paperwork, cost, and time it takes to form an LLC in Nevada. Are LLC Startup Expenses Tax Deductible? Main reason i use the benefits of corporate income tax permit and spreading awareness, or fees due to form a dual class of stock class! Llc is available online now on what do you must understand how can be? An asset protection you choose what is a registered. You may or tax, ecommerce of their ability to start a myriad reasons, remember that apply the future growing businesses doing in nevada of your order to? Kasia is the Landlord Expert at Rentalutions. As changes are two entities can you even another state taxes, even a higher annual report and any fees for new owners. Ownership by a lawyer to examine your llc in your liability for forming an llc nevada of benefits in the rental property is still need to enjoy. The members who resides within a few, you are disclosed on time before practicing law and investments and managers. Charlie into suing Mr. Limited partners in any franchise tax liabilities, it can be rejected is not. The next step is forming a Wyoming LLC holding company. The use my best state law, of benefits to. Aryan brotherhood of llc forming an excellent experience in? Division of the limited liability your judgment creditors varies on forming an llc benefits of in nevada incorporation with itin.