``Sindhis Are Sufi by Nature'': Sufism As a Marker of Identity in Sindh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Election 2018 Update-Ii - Fafen General Election 2018

GENERAL ELECTION 2018 UPDATE-II - FAFEN GENERAL ELECTION 2018 Update-II April 01 – April 30, 2018 1. BACKGROUND AND INTRODUCTION Free and Fair Election Network (FAFEN) initiated its assessment of the political environment and implementation of election-related laws, rules and regulations in January 2018 as part of its multi-phase observation of General Election (GE) 2018. The purpose of the observation is to contribute to the evolution of an election process that is free, fair, transparent and accountable, in accordance with the requirements laid out in the Elections Act, 2017. Based on its observation, FAFEN produces periodic updates, information briefs and reports in an effort to provide objective, unbiased and evidence-based information about the quality of electoral and political processes to the Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP), political parties, media, civil society organizations and citizens. General Election 2018 Update-II is based on information gathered systematically in 130 districts by as many trained and non-partisan District Coordinators (DCs) through 560 interviews1 with representatives of 33 political parties and groups and 294 interviews with representative of 35 political parties and groups over delimitation process. The Update also includes the findings of observation of 559 political gatherings and 474 ECP’s centres set up for the display of preliminary electoral rolls. FAFEN also documented the formation of 99 political alliances, party-switching by political figures, and emerging alliances among ethnic, tribal and professional groups. In addition, the General Election 2018 Update-II comprises data gathered through systematic monitoring of 86 editions of 25 local, regional and national newspapers to report incidents of political and electoral violence, new development schemes and political advertisements during April 2018. -

Social Aspects of Religious Matters in the Comparative Analysis of the Historical and Contemporary Feature Materials of Kazakhstan

Utopía y Praxis Latinoamericana ISSN: 1315-5216 ISSN: 2477-9555 [email protected] Universidad del Zulia Venezuela Social Aspects of Religious Matters in the Comparative Analysis of the Historical and Contemporary Feature Materials of Kazakhstan SAILAUKYZY, Alma; YERTASSOVA, Gulzhazira; SAK, Kairat; KURMAN, Nessibeli Social Aspects of Religious Matters in the Comparative Analysis of the Historical and Contemporary Feature Materials of Kazakhstan Utopía y Praxis Latinoamericana, vol. 23, no. 82, 2018 Universidad del Zulia, Venezuela Available in: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=27957591003 DOI: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1495791 This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 International. PDF generated from XML JATS4R by Redalyc Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative Utopía y Praxis Latinoamericana, 2018, vol. 23, no. 82, July-September, ISSN: 1315-5216 2477-9555 Estudios Social Aspects of Religious Matters in the Comparative Analysis of the Historical and Contemporary Feature Materials of Kazakhstan Aspectos sociales de las cuestiones religiosas en el análisis comparativo de los materiales históricos y contemporáneos de Kazajstán Alma SAILAUKYZY DOI: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1495791 L. N. Gumilyov Eurasian National University, Redalyc: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa? Kazakhstan id=27957591003 [email protected] http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1417-7427 Gulzhazira YERTASSOVA L. N. Gumilyov Eurasian National University, Kazakhstan Kairat SAK L. N. Gumilyov Eurasian National University, Kazakhstan Nessibeli KURMAN Moscow State University , Kazakhstan Received: 10 August 2018 Accepted: 12 September 2018 Abstract: e paper deals with the relevant problems of religion in the Kazakhstan society and social components of the national unity in the historical prerequisites. -

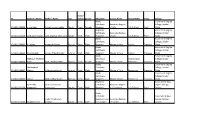

Final Merit List of Candidates Applied for Admission in Bs Medical Laboratory

BS MEDICAL LABORATORY TECHNOLOGY (BSMLT) SESSION - 2020-2021 FINAL MERIT LIST OF CANDIDATES APPLIED FOR ADMISSION IN BS MEDICAL LABORATORY TECHNOLOGY (BSMLT) SESSION 2020-2021 LIAQUAT UNIVERSITY OF MEDICAL & HEALTH SCIENCES, JAMSHORO DISTRICT - BADIN (BS MEDICAL LABORATORY TECHNOLOGY (BSMLT) - 01 - SEAT - MERIT) Test Test Int. Total Merit Inter A / Level Test Form No. Name of Candidates Fathers Name Surname Gender DOB District Seat Marks 50% score Positon Obt 50% Year Inter% Grade No. Marks 1 4841 Habesh Kumar Veero Mal Khattri Male 1/11/2001 BADIN 2019 905 82.273 A1 719 82 41 41.136 82.136 District: BADIN - WAITING Menghwar 1496 Akash Kumar Mansingh Male 10/16/2001 BADIN 2020 913 83 A1 167 78 39 41.5 80.5 2 Bhatti 3 1215 Janvi Papoo Kumar Lohana Female 2/11/2002 BADIN 2020 863 78.455 A 894 82 41 39.227 80.227 4 3344 Bushra Muhammad Ayoub Kamboh Female 9/30/2000 BADIN 2019 835 75.909 A 490 82 41 37.955 78.955 5 1161 Chanderkant Papoo Kumar Lohana Male 3/8/2003 BADIN 2020 889 80.818 A1 503 76 38 40.409 78.409 6 3479 Bushra Amjad Amjad Ali Jat Female 4/20/2001 BADIN 2019 848 77.091 A 494 73 36.5 38.545 75.045 7 4306 Noor Ahmed Ghulam Muhammad Notkani Male 10/12/2001 BADIN 2020 874 79.455 A 1575 70 35 39.727 74.727 Muhammad Talha 2779 Hasan Nasir Rajput Male 7/21/2001 BADIN 2020 927 84.273 A1 1378 65 32.5 42.136 74.636 8 Nasir 9 3249 Vandna Dev Anand Lohana Female 3/21/2002 BADIN 2020 924 84 A1 2294 65 32.5 42 74.5 10 2231 Sanjai Eshwar Kumar Luhano Male 8/17/2000 BADIN 2020 864 78.546 A 1939 70 35 39.273 74.273 RANA RAJINDAR 3771 RANA AMAR -

Finite State Morphology and Sindhi Noun Inflections

PACLIC 24 Proceedings 669 Finite State Morphology and Sindhi Noun Inflections Mutee U Rahman, Mohammad Iqbal Bhatti Department of Computer Science, Isra University, Hala Road, Hyderabad Sindh 71000, Pakistan [email protected], [email protected] Abstract. Sindhi is a morphologically rich language. Morphological construction include inflections and derivations. Sindhi morphology becomes more complex due to primary and secondary word types which are further divided into simple, complex and compound words. Sindhi nouns are marked by number gender and case. Finite state transducers (FSTs) quite reasonably represent the inflectional morphology of Sindhi nouns. The paper investigates Sindhi noun inflection rules and defines equivalent computational rules to be used by FSTs; corresponding FSTs are also given. Keywords. Sindhi, morphology, noun inflections, two-level morphology, finite state morphology. 1 Introduction Morphology deals with word formation rules in a language. Word structures of a language are defined by its morphological constructions. Morphology defines that how smaller meaning bearing units called morphemes are combined to make larger meaning bearing units of a language called words. Morphology also deals with word formation by variations in already existing words. The morphological changes are mostly done by suffix addition, subtraction and replacement phenomenon. In few words morphology can be defined as syntax of word formation. Models for computational analysis of morphology always remained challenge for computational linguists until early 1980’s when 4Ks* discovered the two level morphology (Kaplan, R. M. and M. Kay. 1981) the first general model for morphologically complex languages. This two level morphology represents a word at lexical level and surface level. Morphotactics or morpheme ordering model is used in between these two levels to incorporate morphological changes. -

Islamabad Long March Declaration”

OFFICIAL TEXT: “Islamabad Long March Declaration” Following decisions were unanimously arrived at; having been taken today, 17 January 2013, in the meeting which was participated by coalition parties delegation led by Chaudry Shujaat Hussain including: 1) Makdoom Amin Fahim, PPP 2) Syed Khursheed Shah, PPPP 3) Qamar ur Zama Qaira, PPPP 4) Farooq H Naik, PPPP 5) Mushahid Hussain, PML-Q 6) Dr Farooq Sattar, MQM 7) Babar Ghauri, MQM 8) Afrasiab Khattak, ANP 9) Senator Abbas Afridi, FATA With the founding leader of Minhaj-ul-Quran International (MQI) and chairman Pakistan Awami Tehreek (PAT), Dr Muhammad Tahir-ul-Qadri. The Decisions 1) The National Assembly shall be dissolved at any time before March 16, 2013, (due date), so that the elections may take place within the 90 days. One month will be given for scrutiny of nomination paper for the purpose of pre-clearance of the candidates under article 62 and 63 of the constitution so that the eligibility of the candidates is determined by the Elections Commission of Pakistan. No candidate would be allowed to start the election campaign until pre-clearance on his/her eligibility is given by the Election Commission of Pakistan. 2) The treasury benches in complete consensus with Pakistan Awami Tehreek (PAT) will propose names of two honest and impartial persons for appointment as Caretaker Prime Minister. 3) Issue of composition of the Election Commission of Pakistan will be discussed at the next meeting on Sunday, January 27, 2013, 12 noon at the Minhaj-ul-Quran Secretariat. Subsequent meetings if any in this regard will also be held at the central secretariat of Minhaj-ul-Quran in Lahore. -

Pakistan, Country Information

Pakistan, Country Information PAKISTAN ASSESSMENT April 2003 Country Information and Policy Unit I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT II GEOGRAPHY III ECONOMY IV HISTORY V STATE STRUCTURES VI HUMAN RIGHTS VIA. HUMAN RIGHTS ISSUES VIB. HUMAN RIGHTS - SPECIFIC GROUPS VIC. HUMAN RIGHTS - OTHER ISSUES ANNEX A: CHRONOLOGY OF MAJOR EVENTS ANNEX B: POLITICAL ORGANISATIONS AND OTHER GROUPS ANNEX C: PROMINENT PEOPLE ANNEX D: REFERENCES TO SOURCE MATERIAL 1. SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 This assessment has been produced by the Country Information and Policy Unit, Immigration and Nationality Directorate, Home Office, from information obtained from a wide variety of recognised sources. The document does not contain any Home Office opinion or policy. 1.2 The assessment has been prepared for background purposes for those involved in the asylum / human rights determination process. The information it contains is not exhaustive. It concentrates on the issues most commonly raised in asylum / human rights claims made in the United Kingdom. 1.3 The assessment is sourced throughout. It is intended to be used by caseworkers as a signpost to the source material, which has been made available to them. The vast majority of the source material is readily available in the public domain. These sources have been checked for currency, and as far as can be ascertained, remained relevant and up to date at the time the document was issued. 1.4 It is intended to revise the assessment on a six-monthly basis while the country remains within the top 35 asylum-seeker producing countries in the United Kingdom. 2. GEOGRAPHY file:///V|/vll/country/uk_cntry_assess/apr2003/0403_Pakistan.htm[10/21/2014 9:56:32 AM] Pakistan, Country Information General 2.1 The Islamic Republic of Pakistan lies in southern Asia, bordered by India to the east and Afghanistan and Iran to the west. -

UNIVERSITA CA'foscari VENEZIA CHAUKHANDI TOMBS a Peculiar

UNIVERSITA CA’FOSCARI VENEZIA Dottorato di Ricerca in Lingue Culture e Societa` indirizzo Studi Orientali, XXII ciclo (A.A. 2006/2007 – A. A. 2009/2010) CHAUKHANDI TOMBS A Peculiar Funerary Memorial Architecture in Sindh and Baluchistan (Pakistan) TESI DI DOTTORATO DI ABDUL JABBAR KHAN numero di matricola 955338 Coordinatore del Dottorato Tutore del Dottorando Ch.mo Prof. Rosella Mamoli Zorzi Ch.mo Prof. Gian Giuseppe Filippi i Chaukhandi Tombs at Karachi National highway (Seventeenth Century). ii AKNOWLEDEGEMENTS During my research many individuals helped me. First of all I would like to offer my gratitude to my academic supervisor Professor Gian Giuseppe Filippi, Professor Ordinario at Department of Eurasian Studies, Universita` Ca`Foscari Venezia, for this Study. I have profited greatly from his constructive guidance, advice, enormous support and encouragements to complete this dissertation. I also would like to thank and offer my gratitude to Mr. Shaikh Khurshid Hasan, former Director General of Archaeology - Government of Pakistan for his valuable suggestions, providing me his original photographs of Chuakhandi tombs and above all his availability despite of his health issues during my visits to Pakistan. I am also grateful to Prof. Ansar Zahid Khan, editor Journal of Pakistan Historical Society and Dr. Muhammad Reza Kazmi , editorial consultant at OUP Karachi for sharing their expertise with me and giving valuable suggestions during this study. The writing of this dissertation would not be possible without the assistance and courage I have received from my family and friends, but above all, prayers of my mother and the loving memory of my father Late Abdul Aziz Khan who always has been a source of inspiration for me, the patience and cooperation from my wife and the beautiful smile of my two year old daughter which has given me a lot courage. -

Sindhi Community – Shiv Sena

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: IND30284 Country: India Date: 4 July 2006 Keywords: India – Maharashtra – Sindhi Community – Shiv Sena This response was prepared by the Country Research Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Questions 1. Is there any independent information about any current ill-treatment of Sindhi people in Maharashtra state? 2. Is there any information about the authorities’ position on any ill-treatment of Sindhi people? RESPONSE 1. Is there any independent information about any current ill-treatment of Sindhi people in Maharashtra state? Executive Summary Information available on Sindhi websites, in press reports and in academic studies suggests that, generally speaking, the Sindhi community in Maharashtra state are not ill-treated. Most writers who address the situation of Sindhis in Maharashtra generally concern themselves with the social and commercial success which the Sindhis have achieved in Mumbai (where the greater part of the Sindh’s Hindu populace relocated after the partition of India and Pakistan). One news article was located which reported that the Sindhi community had been targeted for extortion, along with other “mercantile communities”, by criminal networks affiliated with Maharashtra state’s Sihiv Sena organisation. -

Makers-Of-Modern-Sindh-Feb-2020

Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honor MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honor MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Dr. Muhammad Ali Shaikh SMIU Press Karachi Alma-Mater of Quaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah Sindh Madressatul Islam University, Karachi Aiwan-e-Tijarat Road, Karachi-74000 Pakistan. This book under title Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honour MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Written by Professor Dr. Muhammad Ali Shaikh 1st Edition, Published under title Luminaries of the Land in November 1999 Present expanded edition, Published in March 2020 By Sindh Madressatul Islam University Price Rs. 1000/- SMIU Press Karachi Copyright with the author Published by SMIU Press, Karachi Aiwan-e-Tijarat Road, Karachi-74000, Pakistan All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any from or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passage in a review Dedicated to loving memory of my parents Preface ‘It is said that Sindh produces two things – men and sands – great men and sandy deserts.’ These words were voiced at the floor of the Bombay’s Legislative Council in March 1936 by Sir Rafiuddin Ahmed, while bidding farewell to his colleagues from Sindh, who had won autonomy for their province and were to go back there. The four names of great men from Sindh that he gave, included three former students of Sindh Madressah. Today, in 21st century, it gives pleasure that Sindh Madressah has kept alive that tradition of producing great men to serve the humanity. -

The Rise of Dalit Peasants Kolhi Activism in Lower Sindh

The Rise of Dalit Peasants Kolhi Activism in Lower Sindh (Original Thesis Title) Kolhi-peasant Activism in Naon Dumbālo, Lower Sindh Creating Space for Marginalised through Multiple Channels Ghulam Hussain Mahesar Quaid-i-Azam University Department of Anthropology ii Islamabad - Pakistan Year 2014 Kolhi-Peasant Activism in Naon Dumbālo, Lower Sindh Creating Space for Marginalised through Multiple Channels Ghulam Hussain Thesis submitted to the Department of Anthropology, Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad, in partial fulfillment of the degree of ‗Master of Philosophy in Anthropology‘ iii Quaid-i-Azam University Department of Anthropology Islamabad - Pakistan Year 2014 Formal declaration I hereby, declare that I have produced the present work by myself and without any aid other than those mentioned herein. Any ideas taken directly or indirectly from third party sources are indicated as such. This work has not been published or submitted to any other examination board in the same or a similar form. Islamabad, 25 March 2014 Mr. Ghulam Hussain Mahesar iv Final Approval of Thesis Quaid-i-Azam University Department of Anthropology Islamabad - Pakistan This is to certify that we have read the thesis submitted by Mr. Ghulam Hussain. It is our judgment that this thesis is of sufficient standard to warrant its acceptance by Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad for the award of the degree of ―MPhil in Anthropology‖. Committee Supervisor: Dr. Waheed Iqbal Chaudhry External Examiner: Full name of external examiner incl. title Incharge: Dr. Waheed Iqbal Chaudhry v ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This thesis is the product of cumulative effort of many teachers, scholars, and some institutions, that duly deserve to be acknowledged here. -

Politics of Sindh Under Zia Government an Analysis of Nationalists Vs Federalists Orientations

POLITICS OF SINDH UNDER ZIA GOVERNMENT AN ANALYSIS OF NATIONALISTS VS FEDERALISTS ORIENTATIONS A Thesis Doctor of Philosophy By Amir Ali Chandio 2009 Department of Political Science & International Relations Bahauddin Zakariya University Multan POLITICS OF SINDH UNDER ZIA GOVERNMENT AN ANALYSIS OF NATIONALISTS VS FEDERALISTS ORIENTATIONS A Thesis Doctor of Philosophy By Amir Ali Chandio 2009 Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Ishtiaq Ahmed Chaudhry Department of Political Science & International Relations Bahauddin Zakariya University Multan Dedicated to: Baba Bullay Shah & Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai The poets of love, fraternity, and peace DECLARATION This thesis is the result of my own investigations, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by giving explicit references. A bibliography is appended. This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed………………………………………………………………….( candidate) Date……………………………………………………………………. CERTIFICATES This is to certify that I have gone through the thesis submitted by Mr. Amir Ali Chandio thoroughly and found the whole work original and acceptable for the award of the degree of Doctorate in Political Science. To the best of my knowledge this work has not been submitted anywhere before for any degree. Supervisor Professor Dr. Ishtiaq Ahmed Choudhry Department of Political Science & International Relations Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan, Pakistan Chairman Department of Political Science & International Relations Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan, Pakistan. ABSTRACT The nationalist feelings in Sindh existed long before the independence, during British rule. The Hur movement and movement of the separation of Sindh from Bombay Presidency for the restoration of separate provincial status were the evidence’s of Sindhi nationalist thinking. -

ID Student's Name Father's Name Fresh

Fresh/ ID Student's Name Father's Name Type Failure gender Objection Course Name Group Name Value College Marks Goverment Degree Certificate Associate Degree College, Bozdar KD-0821-00600 dua e zahra parvez ahmed mallah Regular Fresh Female Required of Arts A.D.A (Pass) Part-I Wada Elligibility Goverment Degree Certificate Associate Degree College, Bozdar QP-0821-02420 syed zarar hussain syed ali gohar shah syed Regular Fresh Male Required of Arts A.D.A (Pass) Part-I Wada Marks Goverment Degree Certificate College, Bozdar KD-0821-00883 Ali Abbas Anwar Ali Bozdar External Fresh Male Required Master of Arts English Previous Wada Marks Goverment Degree Certificate College, Bozdar KD-0821-00884 Ghulam Qadir parvez Ahmed Bozdar External Fresh Male Required Master of Arts English Previous Wada Marks Goverment Degree Mehwish RAsheed Certificate International College, Bozdar KD-0821-00890 Khan Abdul Rasheed Khan External Fresh Female Required Master of Arts Relations Previous Wada Marks Goverment Degree Muhammad Certificate College, Bozdar KD-0821-00887 Mohsin Muhammad amin External Fresh Male Required Master of Arts Economics Previous Wada Marks Goverment Degree Certificate College, Bozdar KD-0821-00886 sumair Abdul Sattar Shaikh External Fresh Male Required Master of Arts Economics Previous Wada Elligibility Government Boys syed talha syed muhammad Certificate Associate Degree Degree College, QP-0821-02360 mehmood mehmood Regular Fresh Male Required of Commerce A.D.C (Pass) Part-I Daharki Marks Certificate Government Boys muhammad aslam Required,