VCH Summer 2021 Compressed Draft EDITED.Pub

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bridgwater Transport Options Forecast Report

BRIDGWATER TRANSPORT OPTIONS FORECAST REPORT October 2016 BRIDGWATER TRANSPORT OPTIONS FORECAST REPORT Somerset County Council Project no: 287584CQ-PTT Date: October 2016 WSP | Parsons Brinckerhoff Riverside Chambers Castle Street Taunton TA1 4AP www.wspgroup.com www.pbworld.com iv TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 PROJECT BACKGROUND ..........................................................1 1.1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................. 1 1.2 POTENTIAL DEVELOPMENT SITES ............................................................. 1 1.3 MODELLING METHOD STATEMENT ............................................................ 2 1.4 PURPOSE OF THE REPORT ......................................................................... 2 2 FORECAST SCENARIOS ............................................................4 2.1 FORECAST YEARS ....................................................................................... 4 2.2 MODELLED SCENARIOS .............................................................................. 4 3 MODEL OVERVIEW .....................................................................6 3.1 MODEL HISTORY .......................................................................................... 6 3.2 TIME PERIODS .............................................................................................. 6 3.3 USER CLASSES ............................................................................................ 6 4 MODEL LINK VALIDATION .........................................................7 -

South West Ports Association

Chairman: Capt. Brian Murphy (Poole) Vice-Chairman: Capt. Duncan Paul (Falmouth) Hon. Secretary: Capt. Adam Parnell (Tor Bay) Hon. Treasurer Capt. Tim Charlesworth (Cattewater) Accounts/Web site: Ms. Sandra Lynch (Cattewater) www.swrpa.org.uk SOUTH WEST REGIONAL PORTS ASSOCIATION A Directory of Ports and Harbours in the South West Region September 2019 South West Regional Ports Association Directory July 2019 The AIMS of the SOUTH WEST REGIONAL PORTS ASSOCIATION ➢ To provide a forum for ports and harbours within the South West Region to come together for regular discussions on topics affecting ports in the region. ➢ To provide self-help advice and expertise to members. ➢ To provide members with representation at all levels on all topics affecting port and harbour operations. ➢ To co-ordinate attention on issues including environment, leisure and tourism, road and rail links, contingency plans and future development of the South West. ➢ To support and encourage the British Ports Association. ➢ To improve trade using South West ports, particularly within the E.C. ➢ To establish link between ports in the region and the many leisure sure bodies including R.Y.A. Cruising Club, R.N.S.A. diving, fishing, power boating, rowing, 'et skiing and other organisations using harbours. ➢ To provide to the media and others, information and statistics on the ports industry. ➢ To support other bodies and organisations in ensuring the South West receives the necessary support and encouragement from Government and the E.C. ➢ To improve operations and co-operations between South West port members and Devon and Cornwall Constabulary, County Fire Brigades, H.M. Customs and H.M. -

The Town Mill Was Purchased and the Building Reverted to a Corn Mill Early in the 19Th Century, Incorporated As an Extension to the Museum Building

fighting. Underground water cisterns for rainwater storage Blake Museum is run by Bridgwater Town Council and were sometimes constructed in larger house properties, managed by volunteers from The Friends of Blake from which the water could be pumped. Museum (Registered Charity 1099815) Little more information has been found about this water In 1925 Bridgwater Borough Council purchased Blake service. None of the tourists' guidebooks published at the House in Blake Street as a Museum for the town and it end of the 18th century mentioned the waterworks. Joshua was formally opened on April 15 1926. It had been in the Gilpin, the American paper-maker who toured industrial possession of the Blake family - Bridgwater merchants - Bridgwater Town Council Britain between 1795-1805 recording manufacturing and is the reputed birth place of General-at-Sea Robert processes, noted in his diary on May 12 1796 that the Blake (1598-1657) Blake House has interesting town obtained its water from the cistern under the High architectural elements, including timber-framing from the Cross, which was supplied from a nearby stream, so it is late 15th and early 16th century, but was re-modelled in THE BLAKE MUSEUM clear that the plant was still operational then. The High the 17th and 19th centuries. Cross and the cistern were demolished around 1800, and for the next eighty years, during which the population grew As well as material about Bridgwater, it covers the three-fold, and there were frequent severe epidemics, the villages in the area of the old Bridgwater Rural District town depended entirely on rainwater butts and cisterns, Council, extending from just south of Burnham and wells and what water was drawn from the Durleigh Brook Highbridge in the north, to Thurloxton in the south, and and hawked around the houses. -

Bridgwater Station I Onward Travel Information Buses Local Area Map

Bridgwater Station i Onward Travel Information Buses Local area map km Key Key 0 0.5 BC Bridgwater & Taunton College A Bus Stop 0 0.25 Miles EP Eastover Park Rail replacement Bus Stop L Library ce an M Admiral Blake Museum Station Entrance/Exit ist d SC Angel Place Shopping Centre ng ki al Bus Station w s te Cycle routes u n i Footpaths m 0 1 BC SC B Bridgwater Station A L Bridgwater M W e W s Station t on zo yla EP nd R e oad st on zo yl and Road 1 1 0 0 m m i i n n u u t t e e s s w w a a l l k k i i n n g g d d i i s s t t a a n n c c e e Rail replacement buses/coaches will depart from the front of the station Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2018 & also map data © OpenStreetMap contributors, CC BY-SA Main destinations by bus (Data correct at September 2019) DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP Aller 16 B Chedzoy 19 Bus S Stogursey 14 Bus S 19 Bus S Chiltern Polden 75 B* 19 Bus S Ashcott Street 75 B* Combwich 14 Bus S 75 B* Bridgwater Town area - Cossington 75 B* Sutton Mallet 19 Bus S - Bath Road/Bower Lane 14, 19 Bus S Dunball 21 Bus S Taunton ^ 21 Bus S (for Hospital) - Bridgwater Hospital Edington 75 B* Walton 19 Bus S 75 B* (Bower Lane) Glastonbury 75 B* Wells 75 B* - Eastern Avenue 75 B Greinton 19 Bus S Westonzoyland 16 B - Hamp (Wills Road) B1 A Highbridge ^ 21 Bus S Woolavington 75 B* - Haygrove (Durleigh Road) B2 A Huntspill 21 Bus S - Kings Down B1 B Langport 16 B - Polden Meadows 75 B Middlezoy 16 B - Somerset Road 16 B Monkton -

Somerset Routes

Minehead Dunster Blue Anchor Washford Clevedon Clevedon Tyntesfield Oakham Station Station Station Station Lambretta Weston-Super-Mare (Wraxall)Treasures Exmoor Classic West Somerset Scooter Museum Pier Court Car Collection Rural Life Museum Museum (W-s-M) (Portbury) (Porlock) (Allerford) Helicopter Stogursey Castle Kilve Chantry Nether Stowey Castle Brean Down Museum (W-s-M) & Fort Coleridge Cottage Minehead Dunster WorkingDunster CastleDunster DollsBlue Anchor Somerset &Cleeve Dorset Abbey (Nether Stowey) Water Mill Museum Railway MuseumRailway Museum(Washford) Museum of MethodismDovery Manor HolnicoteBurgundy Estate Chapel (Selworthy) (Washford) Burnham-on-Sea From Bristol in West Somerset (Porlock)Museum (Porlock) Watchet Axbridge & Lighthouse District Museum Market House (King John’s Dolebury Warren Museum Brent Knoll Hunting Lodge) Hill Fort Blake Museum Hill Fort Cheddar Caves & Gorge: West Somerset Mineral Railway Watchet (Bridgwater) Museum of Prehistory (Brendon Hills) Boat Museum Somerset Brick Watchet & Tile Museum Ashton Windmill Charterhouse (Bridgwater) Farleigh Hungerford Washford Radio Museum Barford (at Tropiquaria) Sweets Peat and Priddy Barrows Castle Park Westonzoyland Combe Sydenham Hall Pumping Station Science Museum Mells From North Devon Bakelite Museum (Enmore) & Country Park (Monksilver) Fyne Court Museum Wookey (Williton) Frome Museum (Broomfield) Hole Caves West Somerset Railway Battle of Abbot’s Fish & Museum Nunney Castle Cothay Manor and Gardens (Bishops Lydeard) Water Mill & Hestercombe Sedgemoor House -

Flood Risk Management Review Figure 4 Wider Area

305000 310000 315000 320000 325000 330000 335000 340000 345000 350000 355000 360000 Note: The limits, including the height and depths of the Works, shown in this drawing are not to be taken as limiting the obligations of the contractor under Contract. Reproduced by permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of HMSO. 0 0 Bridgwater Bay / Bristol Channel / Severn Estuary © Crown copyright and database rights 2014. 0 5 Ordnance Survey Licence number 100026380 6 1 · Severn Estuary European Marine Site (Severn Estuary/Môr Brean Down Site of Special Scientific Hafren Special Area of Conservation [SAC], Severn Estuary Legend: Interest [SSSI] Special Protection Area [SPA], Severn Estuary RAMSAR Site) Relevant Main · Bridgwater Bay Site of Special Scientific Interest [SSSI] and Watercourses National Nature Reserve [NNR] · High tidal range Somerset Levels and 0 0 · High sediment load 0 Moors (Adjacent to 0 6 · Navigation 1 River Parrett, River · Fishing Weston - super - Mare Sewage Treatment Works (Wessex Water) Tone and King's ST 300 467 Sedgemoor Drain) Boundaries Indicative possible Bridgwater Bay Lagoon location. River Parrett estuary - part of the Statutory 0 Bridgwater Bay 0 Port of Bridgwater, dredged channel 0 5 lagoon 5 1 provides navigation to Bridgwater Hinkley Point power stations intake / outfall M5 Motorway Highbridge and Burnham-on-Sea · Recreational boating A38 0 0 0 0 5 Railway 1 Refer to insert plan Figure 5 Hinkley Point power stations 0 0 Steart Marshes coastal 0 5 4 1 realignment scheme Huntspill River outlet Combwich · Combwich -

Hinkley Point Public Consultation Statement January 2009 …

January 2009 Public Consultation Statement EDF: Plans for New Nuclear Development at Hinkley Point © PPS (Local & Regional) Limited 2009 This document is protected by copyright in the UK and in other countries. No part of this document may be copied or reproduced in any form without the prior consent of PPS (Local & Regional) Limited. PPS (Local & Regional) Limited fully reserves all its legal rights and remedies in respect of any infringement of its copyright. Contents 1. Foreword from EDF..............................................................................................1 2. Introduction ..........................................................................................................3 i Context of the Consultation.........................................................................3 3. Importance of Public Consultation ....................................................................5 i The Planning Process for New Nuclear Power Stations ........................5 ii Central Government Guidance...................................................................5 iii West Somerset Council’s Statement of Community Involvement....................................................................................................6 iv Sedgemoor District Council’s Statement of Community Involvement....................................................................................................8 v EDF’s Commitment ................................................................................... 10 4. Methodology.......................................................................................................11 -

The Ramp FORDGATE, BRIDGWATER, SOMERSET, TA7 0AP

The Ramp FORDGATE, BRIDGWATER, SOMERSET, TA7 0AP The Ramp FORDGATE, BRIDGWATER, SOMERSET, TA7 0AP M5 Junction 2 miles, Taunton 12.5 miles, Bristol Airport 30 miles, Exeter 44 miles Accommodation summary Entrance hall/utility room • Shower room • Study/snug Kitchen • Dining room • Sitting room Master bedrrom with en suite shower room Three further bedrooms • Family bathroom 11 paddocks with field shelters • Woodchip turnout/arena Manège • Two timber stables American barn with six stables and tack room Planning permission for horse walker Double garage • Barn with lapsed planning for conversion In all about 5.36 acres EPC - TBC SAVILLS TAUNTON York House, Blackbrook Business Park, Taunton, Somerset, TA1 2PX 01823 785 441 [email protected] Your attention is drawn to the Important Notice on the last page of the text SITUATION The Ramp is situated in the beautiful Somerset countryside in a rural, yet accessible location within the hamlet of Fordgate. There are an array of excellent canal walks and hacking trails directly from the property. For the Equestrian enthusiast there are top show centres including Stretcholt Equestrian Centre, Kings Sedgemoor, Stockland Lovell, Pontispool, Bicton and Cannington Agricultural College. About 6 miles away from the property are the Quantock Hills, which were England’s first designated Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. The area offers many opportunities for outdoor pursuits and with the surrounding coastline providing superb recreational opportunities. Local facilities maybe found at the small town of North Petherton and Bridgwater some 3 miles distant. There are several well-known public schools in the county town of Taunton where there is a mainline rail link to London Paddington. -

Agenda Document for Heart of the South West (Hotsw)

Phil Norrey Chief Executive (DCC) To: The Chair and Members of the County Hall Heart of the South West Topsham Road (HotSW) Local Enterprise Exeter Partnership (LEP) Joint Devon EX2 4QD Scrutiny Committee (see below) Your ref : Date : 12 June 2019 Email: [email protected] Our ref : Please ask for : Stephanie Lewis 01392 382486 HEART OF THE SOUTH WEST (HOTSW) LOCAL ENTERPRISE PARTNERSHIP (LEP) JOINT SCRUTINY COMMITTEE Thursday, 20th June, 2019 A meeting of the Heart of the South West (HotSW) Local Enterprise Partnership (LEP) Joint Scrutiny Committee is to be held on the above date, at 2.15 pm at Committee Suite - County Hall to consider the following matters. PHIL NORREY Chief Executive A G E N D A 1 Apologies PART I - OPEN COMMITTEE 2 Minutes (Pages 1 - 4) Minutes of the meeting held on 14 February 2019, attached. 3 Items Requiring Urgent Attention Items which in the opinion of the Chairman should be considered at the meeting as matters of urgency. MATTERS FOR CONSIDERATION OR REVIEW 4 Local Industrial Strategy (Pages 5 - 60) Report of the Chief Executive of the Local Enterprise Partnership, attached. 5 Acceleration of Housing Delivery in the Heart of the South West (Pages 61 - 66) Report of the Heart of the South West Joint Committee presented by the Chief Executive of the Local Enterprise Partnership, attached. MATTERS FOR INFORMATION 6 Scrutiny Work Programme In accordance with previous practice, Scrutiny Committees are requested to review the list of forthcoming business and determine which items are to be included in the Work Programme. -

UKHO Releases Enhanced Chart Coverage of Bridgwater Bay

Press Release 28 February 2019 UKHO releases enhanced chart coverage of Bridgwater Bay UK Hydrographic Office produces upgraded chart to support developments in Somerset The Taunton-headquartered UK Hydrographic Office (UKHO) has released a new chart providing enhanced coverage of Bridgwater Bay and the River Parrett. The upgraded chart is available as both an Electronic Navigational Chart (ENC) and in paper format, helping mariners to plan and execute safe and efficient voyages, supporting wider infrastructure development in the area as well as benefiting the local economy. The chart covers the approach to the River Parrett across Bridgwater Bay and south-eastwards to the river berths of Combwich and Dunball. Supporting and enabling safe passage at sea is at the core of what the UKHO does, and the upgraded chart is essential for safe operational use of the Hinkley Point C Harbour to transport construction materials and equipment for the immense construction project. The UKHO worked closely with the Harbour Masters at Hinkley Point C Harbour and Port of Bridgwater to define the new chart limits and scale, along with ensuring that appropriate hydrographic surveys and details of the new developments were available to produce the chart. Chris Berkley, Master Mariner and Product Manager at UKHO, commented: “We are pleased to be able to release new and improved scale electronic and paper charts which give ships access to more detailed, highly accurate information that can support safe passage. To be able to support infrastructure development close to our headquarters and provide mariners with the tools they need to navigate Bridgwater Bay with confidence is a great example of how the local economy can benefit from our expertise.” ---------------------- ENDS Notes to Editors About the UK Hydrographic Office The UK Hydrographic Office is a leading centre for hydrography, providing marine geospatial data to inform maritime decisions. -

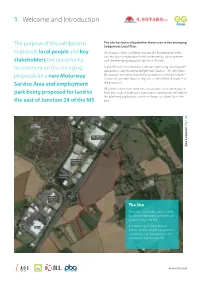

1 Welcome and Introduction

1 Welcome and Introduction The site has been allocated for these uses in the emerging The purpose of this exhibition is Sedgemoor Local Plan. to provide local people and key The boards in this exhibition set out the background to the site, the key considerations and constraints to development stakeholders the opportunity and the emerging proposals for the 32Ha site. In parallel with this exhibition, we are submitting a formal pre- to comment on the emerging application submission to Sedgemoor Council. This will allow the council and other stakeholders, such as Somerset County proposals for a new Motorway Council, to provide input as regards to the technical aspects of Service Area and employment the proposals. All of the information from this consultation and the response park being proposed for land to from the Council to the pre-application submission, will inform the planning application, which we hope to submit later this the east of Junction 24 of the M5. year. Plan Argos Distribution Centre Site Location Location Site Huntworth Business Park M5 Bridgwater Services Junction Sedgemoor 24 Auction Rooms The Site The site is 32 ha (85 acres) of land located immediately to the east of junction 24 of the M5. Muller It is made up of three distinct parcels of land which are adjacent to junction J24, between the M5 motorway and Huntworth. www.lhc.net 2 Planning Policy The land is identified as Policy B9 Land at Huntworth, East of J.24 in the emerging Sedgemoor Local Plan. The Current Wording of Policy B9 is; Indicative Plan - Emerging Sedgemoor Local Plan Land at Huntworth, East of J.24 Land at Huntworth, East of J.24, Bridgwater (as defined on the Policies Map) is allocated for employment development. -

Grassedandplantedareas by Motorways

GRASSEDANDPLANTEDAREAS BY MOTORWAYS A REPORT BASED ON INFORMATION GIVEN IN 1974175 BY THE DEPARTMENT OF THE ENVIRONMENT AND COUNTY COUNCIL HIGHWAY DEPARTMENTS, WITH ADDITIONAL DATA FROM OTHER SOURCES J. M. WAY T.D.. M.Sc., Ph.D. 1976 THE INSTITUTE OF TERRESTRIAL ECOLOGY I MONKS WOOD EXPERIMENTAL STATION .ARROTS. - - - . - .RIPTON .. - . HUNTINGDON PE 17 2LS I CAMBRIDGESHIRE INDEX Page Chapter 1 Introduction. 1 Chapter 2 Distribution and mileage of motorways, with estimates of acreage of grassed and planted areas. Chapter 3 Geology and land use. Chapter 4 Grass and herbaceous plants. Chapter 5 Planting and maintenance of trees and shrubs. Chapter 6 Analysis of reasons for managing grassed areas and attitudes towards their management. Chapter 7 Management of grassed areas on motorway banks and verges in 1974. Chapter 8 Ditches, Drains, Fences and Hedges. Chapter 9 Central Reservations. Chapter 10 Pollution and litter. Chapter 11 Costs of grass management in 1974. Summary and Conclusions Aclolowledgements Bibliography Appendix Figures Appendix Tables iii INDEX Page TEXT TABLES Table 1 Occurrences of different land uses by motorways. Monks Wood field data. Table 2 Occurrences of different land uses by motorways. Data from maps. Table 3 Special grass mixtures used by motorways. Table 4 Annual totals of trees and shrubs planted by motorways 1963-1974. Table 5 Numbers of individual species of trees and shrubs planted by motorways in the three seasons 1971/72 to 1973/74- APPENDIX FIGURES Figure 1 General distribution of motorways in England and Wales, 1974. Figure 2 The M1, M10, M18, M45, M606 and M621. Southern and midland parts of the Al(M).