Balfour Declaration of 1917

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arab-Israeli Relations

FACTSHEET Arab-Israeli Relations Sykes-Picot Partition Plan Settlements November 1917 June 1967 1993 - 2000 May 1916 November 1947 1967 - onwards Balfour 1967 War Oslo Accords which to supervise the Suez Canal; at the turn of The Balfour Declaration the 20th century, 80% of the Canal’s shipping be- Prepared by Anna Siodlak, Research Associate longed to the Empire. Britain also believed that they would gain a strategic foothold by establishing a The Balfour Declaration (2 November 1917) was strong Jewish community in Palestine. As occupier, a statement of support by the British Government, British forces could monitor security in Egypt and approved by the War Cabinet, for the establish- protect its colonial and economic interests. ment of a national home for the Jewish people in Palestine. At the time, the region was part of Otto- Economics: Britain anticipated that by encouraging man Syria administered from Damascus. While the communities of European Jews (who were familiar Declaration stated that the civil and religious rights with capitalism and civil organisation) to immigrate of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine to Palestine, entrepreneurialism and development must not be deprived, it triggered a series of events would flourish, creating economic rewards for Brit- 2 that would result in the establishment of the State of ain. Israel forcing thousands of Palestinians to flee their Politics: Britain believed that the establishment of homes. a national home for the Jewish people would foster Who initiated the declaration? sentiments of prestige, respect and gratitude, in- crease its soft power, and reconfirm its place in the The Balfour Declaration was a letter from British post war international order.3 It was also hoped that Foreign Secretary Lord Arthur James Balfour on Russian-Jewish communities would become agents behalf of the British government to Lord Walter of British propaganda and persuade the tsarist gov- Rothschild, a prominent member of the Jewish ernment to support the Allies against Germany. -

Steps to Statehood Timeline

STEPS TO STATEHOOD TIMELINE Tags: History, Leadership, Balfour, Resources 1896: Theodor Herzl's publication of Der Judenstaat ("The Jewish State") is widely considered the foundational event of modern Zionism. 1917: The British government adopted the Zionist goal with the Balfour Declaration which views with favor the creation of "a national home for the Jewish people." / Balfour Declaration Feb. 1920: Winston Churchill: "there should be created in our own lifetime by the banks of the Jordan a Jewish State." Apr. 1920: The governments of Britain, France, Italy, and Japan endorsed the British mandate for Palestine and also the Balfour Declaration at the San Remo conference: The Mandatory will be responsible for putting into effect the declaration originally made on November 8, 1917, by the British Government, and adopted by the other Allied Powers, in favour of the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people. July 1922: The League of Nations further confirmed the British Mandate and the Balfour Declaration. 1937: Lloyd George, British prime minister when the Balfour Declaration was issued, clarified that its purpose was the establishment of a Jewish state: it was contemplated that, when the time arrived for according representative institutions to Palestine, / if the Jews had meanwhile responded to the opportunities afforded them ... by the idea of a national home, and had become a definite majority of the inhabitants, then Palestine would thus become a Jewish commonwealth. July 1937: The Peel Commission: 1. "if the experiment of establishing a Jewish National Home succeeded and a sufficient number of Jews went to Palestine, the National Home might develop in course of time into a Jewish State." 2. -

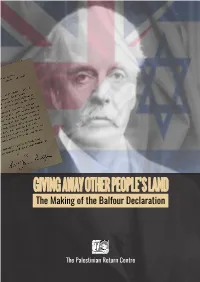

The Making of the Balfour Declaration

The Making of the Balfour Declaration The Palestinian Return Centre i The Palestinian Return Centre is an independent consultancy focusing on the historical, political and legal aspects of the Palestinian Refugees. The organization offers expert advice to various actors and agencies on the question of Palestinian Refugees within the context of the Nakba - the catastrophe following the forced displacement of Palestinians in 1948 - and serves as an information repository on other related aspects of the Palestine question and the Arab-Israeli conflict. It specializes in the research, analysis, and monitor of issues pertaining to the dispersed Palestinians and their internationally recognized legal right to return. Giving Away Other People’s Land: The Making of the Balfour Declaration Editors: Sameh Habeeb and Pietro Stefanini Research: Hannah Bowler Design and Layout: Omar Kachouch All rights reserved ISBN 978 1 901924 07 7 Copyright © Palestinian Return Centre 2017 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publishers or author, except in the case of a reviewer, who may quote brief passages embodied in critical articles or in a review. مركز العودة الفلسطيني PALESTINIAN RETURN CENTRE 100H Crown House North Circular Road, London NW10 7PN United Kingdom t: 0044 (0) 2084530919 f: 0044 (0) 2084530994 e: [email protected],uk www.prc.org.uk ii Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................3 -

Down with Britain, Away with Zionism: the 'Canaanites'

DOWN WITH BRITAIN, AWAY WITH ZIONISM: THE ‘CANAANITES’ AND ‘LOHAMEY HERUT ISRAEL’ BETWEEN TWO ADVERSARIES Roman Vater* ABSTRACT: The imposition of the British Mandate over Palestine in 1922 put the Zionist leadership between a rock and a hard place, between its declared allegiance to the idea of Jewish sovereignty and the necessity of cooperation with a foreign ruler. Eventually, both Labour and Revisionist Zionism accommodated themselves to the new situation and chose a strategic partnership with the British Empire. However, dissident opinions within the Revisionist movement were voiced by a group known as the Maximalist Revisionists from the early 1930s. This article analyzes the intellectual and political development of two Maximalist Revisionists – Yonatan Ratosh and Israel Eldad – tracing their gradual shift to anti-Zionist positions. Some questions raised include: when does opposition to Zionist politics transform into opposition to Zionist ideology, and what are the implications of such a transition for the Israeli political scene after 1948? Introduction The standard narrative of Israel’s journey to independence goes generally as follows: when the British military rule in Palestine was replaced in 1922 with a Mandate of which the purpose was to implement the 1917 Balfour Declaration promising support for a Jewish ‘national home’, the Jewish Yishuv in Palestine gained a powerful protector. In consequence, Zionist politics underwent a serious shift when both the leftist Labour camp, led by David Ben-Gurion (1886-1973), and the rightist Revisionist camp, led by Zeev (Vladimir) Jabotinsky (1880-1940), threw in their lot with Britain. The idea of the ‘covenant between the Empire and the Hebrew state’1 became a paradigm for both camps, which (temporarily) replaced their demand for a Jewish state with the long-term prospect of bringing the Yishuv to qualitative and quantitative supremacy over the Palestinian Arabs under the wings of the British Empire. -

Tamar Amar-Dahl Zionist Israel and the Question of Palestine

Tamar Amar-Dahl Zionist Israel and the Question of Palestine Tamar Amar-Dahl Zionist Israel and the Question of Palestine Jewish Statehood and the History of the Middle East Conflict First edition published by Ferdinand Schöningh GmbH & Co. KG in 2012: Das zionistische Israel. Jüdischer Nationalismus und die Geschichte des Nahostkonflikts An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. ISBN 978-3-11-049663-5 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-049880-6 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-049564-5 ISBN 978-3-11-021808-4 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-021809-1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-021806-2 A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. ISSN 0179-0986 e-ISSN 0179-3256 Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 License, © 2017 Tamar Amar-Dahl, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston as of February 23, 2017. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. -

Piety and Mayhem: How Extremist Groups Misuse Religious Doctrine to Condone Violence and Achieve Political Goals

Ursinus College Digital Commons @ Ursinus College Religious Studies Honors Papers Student Research 5-4-2020 Piety and Mayhem: How Extremist Groups Misuse Religious Doctrine to Condone Violence and Achieve Political Goals Noah Garber Ursinus College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/rel_hon Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Buddhist Studies Commons, Ethics in Religion Commons, Islamic Studies Commons, Jewish Studies Commons, Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons, Peace and Conflict Studies Commons, Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons, and the Terrorism Studies Commons Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Garber, Noah, "Piety and Mayhem: How Extremist Groups Misuse Religious Doctrine to Condone Violence and Achieve Political Goals" (2020). Religious Studies Honors Papers. 3. https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/rel_hon/3 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at Digital Commons @ Ursinus College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religious Studies Honors Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Ursinus College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Piety and Mayhem: How Extremist Groups Misuse Religious Doctrine to Condone Violence and Achieve Political Goals Noah Garber May 4, 2020 Submitted to the Faculty of Ursinus College in fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Departments of Politics and Religious Studies 1 Abstract This thesis examines the way in which various groups have used religion as a justification for violent action towards political ends. From the Irgun, which carried out terrorist acts in Palestine, to the Palestinian Islamist organization Hamas, which has waged war on Israel, to the Buddhist leadership of Myanmar, which has waged a genocidal campaign against Rohingya Muslims living in the country, these groups have employed a narrow interpretation of their religious texts as a means to justify the actions they take. -

The Jewish State

The Jewish State Der Judenstaat Theodor Herzl 1896 Translated from the German by Sylvie D'Avigdor Adapted from the edition published in 1946 by the American Zionist Emergency Council Proofread and corrected by MidEastWeb, with a preface by Ami Isseroff. PDF e-book compiled by MidEastWeb http://www.MidEastweb.org for distribution free of charge. About MidEastWeb MidEastWeb is dedicated to promoting understanding between the peoples of the Middle East through education for peace, promotion of dialog, and dissemination of balanced information. To this end, MidEastWeb maintains a Web site at http://www.mideastweb.org, including numerous historical sources, and downloadable materials such as this PDF file and a downloadable translation of the Qur'an. Please tell friends about MidEastWeb. MidEastWeb materials may be printed and distributed free of charge provided credit is given to MidEastWeb at http://www.mideastweb.org. Please do not copy materials from MidEastWeb to your Web site. Please link to us and tell people about MidEastWeb. TABLE OF CONTENTS The Jewish State: MidEastWeb Preface............................................................... 1 I n t r o d u c t i o n ............................................................................................... 4 T h e .. J e w i s h. Q u e s t i o n ........................................................................ 10 T h e .. J e w i s h .. C o m p a n y ...................................................................... 17 L o c a l G r o u p s ............................................................................................ 30 Society of Jews and Jewish State ...................................................................... 37 Conclusion __________..................................................................................... 47 The Jewish State - Theodore Herzl - 1896 The Jewish State: MidEastWeb Preface Theodore Herzl's pamphlet Der Judenstaat, The Jewish State, was published in 1896. -

"Hnzono Shel Hazony,"

David N. Myers 'ue ts, ,td "Hnzono Shel HAzony," )o^b or "Even If You'\7ill It, It Can Still Be a Dream" :d T rN oNp oF THE sEsr bookreviews everpublished, thephilosopherRobert Paul \Tolffperformed a diabolically clever trompe I'eil onAllan Bloomt Allan Bloom as its protagonist. I must confess that, when reading Yoram Hazony's The Jewish State: The Snuggle for Israeli Soul,2 I am reminded of the Bloom satire. This is not only because Hezony has a Bloomian (read conspiratorial) fear of the devious designs of liberal academics. Nor is it his considerable powers of reductionism that grind down complex and often disparate chunks of history into a neat pile of dust-all the easier to blow away with glee. It is also because Hazonywas educated and intellectuallyformed in the United States in the midst of debate over Tbe Closing of the American Mind, end hence smack in the middle of the "culrure wars" berween the academic left and right. The result is that The Jewish state bears the deep imprint of a r98os-style, American neo-conservative sensibiliry and sense of mission. 'S7hen transposed onto the Israeli cultural landscape, this stamp seems inauthentic, like an elaborately designed coat of arms for an arriaiste, As a work of history, which it purports to be in part, TheJewish State is deeply flawed-to the point rhat the reader often has an easier time imagining it as a work of fiction. In this regard, it is tempting to consider Yoram Hazony as a younger Israeli version of Saul Bellow's Allan Bloom (who has now been given full novelistic horiors in the recent Rnuelsteins). -

Herzl and Zionism

Herzl and Zionism Binyamin Ze'ev Herzl (1860-1904 ) "In Basle I founded the Jewish state...Maybe in five years, certainly in fifty, everyone will realize it.” Theodor (Binyamin Ze'ev) Herzl, the father of modern political Zionism, was born in Budapest in 1860. He was educated in the spirit of the German-Jewish Enlightenment of the period, learning to appreciate secular culture. In 1878 the family moved to Vienna, and in 1884 Herzl was awarded a doctorate of law from the University of Vienna. He became a writer, a playwright and a journalist. Herzl became the Paris correspondent of the influential liberal Vienna newspaper Neue Freie Presse. Herzl first encountered the antisemitism that would shape his life and the fate of the Jews in the twentieth century while studying at the University of Vienna (1882). Later, during his stay in Paris as a journalist, he was brought face-to-face with the problem. At the time, he regarded the Jewish problem as a social issue Herzl at Basle (1898) (Central Zionist Archives) In 1894, Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish officer in the French army, was unjustly accused of treason, mainly because of the prevailing antisemitic atmosphere. Herzl witnessed mobs shouting "Death to the Jews". He resolved that there was only one solution to this antisemitic assault: the mass immigration of Jews to a land that they could call their own. Thus the Dreyfus case became one of the determinants in the genesis of political Zionism. Herzl concluded that antisemitism was a stable Herzl with Zionist delegation en route to Israel (1898) and immutable factor in human society, which (Israel Government Press Office) assimilation did not solve. -

Deir Yassin Massacre (1948)

Document B The 1948 War Deir Yassin Massacre Deir Yassin Massacre (1948) Early in the morning of April 9, 1948, commandos of the Irgun (headed by Menachem Begin) and the Stern Gang attacked Deir Yassin, a village with about 750 Palestinian residents. The village lay outside of the area to be assigned by the United Nations to the Jewish State; it had a peaceful reputation. But it was located on high ground in the corridor between Tel Aviv and Jerusalem. Deir Yassin was slated for occupation under Plan Dalet and the mainstream Jewish defense force, the Haganah, authorized the irregular terrorist forces of the Irgun and the Stern Gang to perform the takeover. In all over 100 men, women, and children were systematically murdered. Fifty-three orphaned children were literally dumped along the wall of the Old City, where they were found by Miss Hind Husseini and brought behind the American Colony Hotel to her home, which was to become the Dar El-Tifl El-Arabi orphanage. (source: http://www.deiryassin.org) Natan Yellin-Mor (Jewish) responded to the massacre: When I remember what led to the massacre of my mother, sister and other members of my family, I can’t accept this massacre. I know that in the heat of battle such things happen, and I know that the people who do these things don’t start out with such things in mind. They kill because their own comrades have being killed and wounded, and they want their revenge at that very moment. But who tells them to be proud of such deeds? (From Eyal naveh and Eli bar-Navi, Modern Times, part 2, page 228) One of the young men of the Deir Yassin village reported what he has been told by his mother: My mother escaped with my two small brothers, one-year old and two-years old. -

Zionist Perspectives from Herzl to Begin Syllabus (PDF)

Political Zionism and Covenantal Judaism: Zionist Perspectives from Herzl to Begin An Honors First Year Writing Course Throughout its history, two different facets of the Zionist project have either existed in tension with each other, or complemented one another. On the one hand, Israel is, and seeks to be, a flourishing democratic state that makes manifest the modern Jewish right to national self-determination. On the other hand, Zionism has long claimed to represent the covenantal, religious longings of Jews over millennia. The goal of this course is to examine how these two facets of the Zionist project are reflected in the worldview and career of one of the most influential leaders of modern Israel: Menachem Begin. The course will first trace the roots of modern Zionism in general, and Revisionist Zionism in particular, by focusing on the writings of Theodore Herzl and Ze'ev (Vladimir) Jabotinsky. We will then focus on some of the seminal and controversial moments in Begin's life, beginning with those that occurred before his election as Prime Minister: the revolution against the British mandate; the tensions between Begin and Ben- Gurion and the Altalena incident; the debate over whether the nascent State of Israel should accept reparations from Germany; Knesset discussions over the role religion would play in defining the national culture of the state; and the unity cabinet during the Six Day War. The second part of the course will examine moments in Begin's administration that continue to impact Israel today: The peace treaty with Egypt;; the strike against the Iraqi nuclear reactor; and the Lebanon war. -

The Rise of the Zionist Right: Polish Jews and the Betar Youth Movement, 1922-1935

THE RISE OF THE ZIONIST RIGHT: POLISH JEWS AND THE BETAR YOUTH MOVEMENT, 1922-1935 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AND THE COMMITTEE ON GRADUATE STUDIES OF STANFORD UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Daniel K. Heller August 2012 © 2012 by Daniel Kupfert Heller. All Rights Reserved. Re-distributed by Stanford University under license with the author. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial 3.0 United States License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/us/ This dissertation is online at: http://purl.stanford.edu/bd752jg9919 ii I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Steven Zipperstein, Primary Adviser I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Norman Naimark I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Aron Rodrigue Approved for the Stanford University Committee on Graduate Studies. Patricia J. Gumport, Vice Provost Graduate Education This signature page was generated electronically upon submission of this dissertation in electronic format. An original signed hard copy of the signature page is on file in University Archives. iii ABSTRACT This dissertation charts the social, cultural and intellectual development of the Zionist Right through an examination of the Brit Yosef Trumpeldor youth movement, known eventually by its Hebrew acronym, Betar.