Ancient Times the Land That Now Encompasses Israel and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Terrorism: Individuals: Atta [Mahmoud] Box: RAC Box 8](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1820/terrorism-individuals-atta-mahmoud-box-rac-box-8-11820.webp)

Terrorism: Individuals: Atta [Mahmoud] Box: RAC Box 8

Ronald Reagan Presidential Library Digital Library Collections This is a PDF of a folder from our textual collections. Collection: Counterterrorism and Narcotics, Office of, NSC: Records Folder Title: Terrorism: Individuals: Atta [Mahmoud] Box: RAC Box 8 To see more digitized collections visit: https://reaganlibrary.gov/archives/digital-library To see all Ronald Reagan Presidential Library inventories visit: https://reaganlibrary.gov/document-collection Contact a reference archivist at: [email protected] Citation Guidelines: https://reaganlibrary.gov/citing National Archives Catalogue: https://catalog.archives.gov/ WITHDRAWAL SHEET Ronald Reagan Library Collection Name COUNTERTERRORISM AND NARCOTICS, NSC: Withdrawer RECORDS SMF 5/12/2010 File Folder TERRORISM: INDNIDUALS: ATTA [ITA, MAHMOUD] FOIA TED MCNAMARA, NSC STAFF F97-082/4 Box Number _w;:w (2j!t t ~ '( £ WILLS 5 ID Doc Type Document Description No of Doc Date Restrictions Pages 91194 REPORT RE ABU NIDAL ORGANIZATION (ANO) 1 ND Bl B3 - ·-----------------·--------------- ------ -------- 91195 MEMO CLARKE TO NSC RE MAHMOUD ITA 2 5/6/1987 B 1 B3 ---------------------- ------------ ------ ------ ----- ----------- 91196 MEMO DUPLICATE OF 91195 2 5/6/1987 Bl B3 91197 REPORT REATTA 1 ND Bl 91198 CABLE STATE 139474 2 5112/1987 Bl 91199 CABLE KUWAIT 03413 1 5/2111987 Bl -- - - - - --------- - - -- - ----------------- 91200 CABLE l 5 l 525Z MAR 88 (1 ST PAGE ONLY) 1 3/15/1988 Bl B3 The above documents were not referred for declassification review at time of processing Freedom of Information -

World War I Concept Learning Outline Objectives

AP European History: Period 4.1 Teacher’s Edition World War I Concept Learning Outline Objectives I. Long-term causes of World War I 4.1.I.A INT-9 A. Rival alliances: Triple Alliance vs. Triple Entente SP-6/17/18 1. 1871: The balance of power of Europe was upset by the decisive Prussian victory in the Franco-Prussian War and the creation of the German Empire. a. Bismarck thereafter feared French revenge and negotiated treaties to isolate France. b. Bismarck also feared Russia, especially after the Congress of Berlin in 1878 when Russia blamed Germany for not gaining territory in the Balkans. 2. In 1879, the Dual Alliance emerged: Germany and Austria a. Bismarck sought to thwart Russian expansion. b. The Dual Alliance was based on German support for Austria in its struggle with Russia over expansion in the Balkans. c. This became a major feature of European diplomacy until the end of World War I. 3. Triple Alliance, 1881: Italy joined Germany and Austria Italy sought support for its imperialistic ambitions in the Mediterranean and Africa. 4. Russian-German Reinsurance Treaty, 1887 a. It promised the neutrality of both Germany and Russia if either country went to war with another country. b. Kaiser Wilhelm II refused to renew the reinsurance treaty after removing Bismarck in 1890. This can be seen as a huge diplomatic blunder; Russia wanted to renew it but now had no assurances it was safe from a German invasion. France courted Russia; the two became allies. Germany, now out of necessity, developed closer ties to Austria. -

Terrorist Links of the Iraqi Regime | the Washington Institute

MENU Policy Analysis / PolicyWatch 652 Terrorist Links of the Iraqi Regime Aug 29, 2002 Brief Analysis n August 28, 2002, a U.S. federal grand jury issued a new indictment against five terrorists from the Fatah O Revolutionary Command, also known as the Abu Nidal Organization (ANO), for the 1986 hijacking of Pan Am Flight 73 in Karachi, Pakistan. Based on "aggravating circumstances," prosecutors are now seeking the death penalty for the attack, in which twenty-two people -- including two Americans -- were killed. The leader of the ANO, the infamous Palestinian terrorist Abu Nidal (Sabri al-Banna), died violently last week in Baghdad. But his death is not as extraordinary as the subsequent press conference given by Iraqi intelligence chief Taher Jalil Haboush. This press conference represents the only time Haboush's name has appeared in the international media since February 2001. Iraqi Objectives What motivated the Iraqi regime to send one of its senior exponents to announce the suicide of Abu Nidal and to present crude photographs of his bloodied body four days (or eight days, according to some sources) after his death? It should be noted that the earliest information about Nidal's death came from al-Ayyam, a Palestinian daily close to the entity that may have been Abu Nidal's biggest enemy -- the Palestinian Authority. At this sensitive moment in U.S.-Iraqi relations, Abu Nidal could have provided extraordinarily damaging testimony with regard to Saddam's involvement in international terrorism, even beyond Iraqi support of ANO activities in the 1970s and 1980s. In publicizing Nidal's death, the regime's motives may have been multiple: • To present itself as fighting terrorism by announcing that Iraqi authorities were attempting to detain Abu Nidal for interrogation in the moments before his death. -

Israeli Settlement Goods

British connections with Israeli Companies involved in the Trade union briefing settlements settlements Key Israeli companies which export settlement products to the Over 50% of Israel’s agricultural produce is imported by UK are: the European Union, of which a large percentage arrives in British stores, including all the main supermarkets. These Agricultural Export Companies: Carmel-Agrexco, Hadiklaim, include: Asda, Tesco, Waitrose, John Lewis, Morrisons, and Mehadrin-Tnuport, Arava, Jordan River, Jordan Plains, Flowers Sainsburys. Direct Other food products: Abady Bakery, Achdut, Adumim Food ISRAELI SETTLEMENT The Soil Association aids the occupation by providing Additives/Frutarom, Amnon & Tamar, Oppenheimer, Shamir certification to settlement products. Salads, Soda Club In December 2009, following significant consumer pressure, Dead Sea Products: Ahava, Dead Sea Laboratories, Intercosma the Department for Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) issued GOODS: BAN THEM, guidelines for supermarkets on settlement labeling — Please note that some of these companies also produce differentiating goods grown in settlements from goods legitimate goods in Israel. It is goods from the illegal grown on Palestinian farms. Although this guidance is not settlements that we want people to boycott. compulsory, many supermarkets are already saying that they don’t buy THEM! will adopt this labeling, so consumers will know if goods Companies working in the are grown in illegal Israeli settlements. DEFRA also stated that companies will be committing an offence -

Forming a Nucleus for the Jewish State

Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................... 3 Jewish Settlements 70 CE - 1882 ......................................................... 4 Forming a Nucleus for First Aliyah (1882-1903) ...................................................................... 5 Second Aliyah (1904-1914) .................................................................. 7 the Jewish State: Third Aliyah (1919-1923) ..................................................................... 9 First and Second Aliyot (1882-1914) ................................................ 11 First, Second, and Third Aliyot (1882-1923) ................................... 12 1882-1947 Fourth Aliyah (1924-1929) ................................................................ 13 Fifth Aliyah Phase I (1929-1936) ...................................................... 15 First to Fourth Aliyot (1882-1929) .................................................... 17 Dr. Kenneth W. Stein First to Fifth Aliyot Phase I (1882-1936) .......................................... 18 The Peel Partition Plan (1937) ........................................................... 19 Tower and Stockade Settlements (1936-1939) ................................. 21 The Second World War (1940-1945) ................................................ 23 Postwar (1946-1947) ........................................................................... 25 11 Settlements of October 5-6 (1947) ............................................... 27 First -

Arab-Israeli Relations

FACTSHEET Arab-Israeli Relations Sykes-Picot Partition Plan Settlements November 1917 June 1967 1993 - 2000 May 1916 November 1947 1967 - onwards Balfour 1967 War Oslo Accords which to supervise the Suez Canal; at the turn of The Balfour Declaration the 20th century, 80% of the Canal’s shipping be- Prepared by Anna Siodlak, Research Associate longed to the Empire. Britain also believed that they would gain a strategic foothold by establishing a The Balfour Declaration (2 November 1917) was strong Jewish community in Palestine. As occupier, a statement of support by the British Government, British forces could monitor security in Egypt and approved by the War Cabinet, for the establish- protect its colonial and economic interests. ment of a national home for the Jewish people in Palestine. At the time, the region was part of Otto- Economics: Britain anticipated that by encouraging man Syria administered from Damascus. While the communities of European Jews (who were familiar Declaration stated that the civil and religious rights with capitalism and civil organisation) to immigrate of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine to Palestine, entrepreneurialism and development must not be deprived, it triggered a series of events would flourish, creating economic rewards for Brit- 2 that would result in the establishment of the State of ain. Israel forcing thousands of Palestinians to flee their Politics: Britain believed that the establishment of homes. a national home for the Jewish people would foster Who initiated the declaration? sentiments of prestige, respect and gratitude, in- crease its soft power, and reconfirm its place in the The Balfour Declaration was a letter from British post war international order.3 It was also hoped that Foreign Secretary Lord Arthur James Balfour on Russian-Jewish communities would become agents behalf of the British government to Lord Walter of British propaganda and persuade the tsarist gov- Rothschild, a prominent member of the Jewish ernment to support the Allies against Germany. -

To Examine the Horrors of Trench Warfare

TRENCH WARFARE Objective: To examine the horrors of trench warfare. What problems faced attacking troops? What was Trench Warfare? Trench Warfare was a type of fighting during World War I in which both sides dug trenches that were protected by mines and barbed wire Cross-section of a front-line trench How extensive were the trenches? An aerial photograph of the opposing trenches and no-man's land in Artois, France, July 22, 1917. German trenches are at the right and bottom, British trenches are at the top left. The vertical line to the left of centre indicates the course of a pre-war road. What was life like in the trenches? British trench, France, July 1916 (during the Battle of the Somme) What was life like in the trenches? French soldiers firing over their own dead What were trench rats? Many men killed in the trenches were buried almost where they fell. These corpses, as well as the food scraps that littered the trenches, attracted rats. Quotes from soldiers fighting in the trenches: "The rats were huge. They were so big they would eat a wounded man if he couldn't defend himself." "I saw some rats running from under the dead men's greatcoats, enormous rats, fat with human flesh. My heart pounded as we edged towards one of the bodies. His helmet had rolled off. The man displayed a grimacing face, stripped of flesh; the skull bare, the eyes devoured and from the yawning mouth leapt a rat." What other problems did soldiers face in the trenches? Officers walking through a flooded communication trench. -

Steps to Statehood Timeline

STEPS TO STATEHOOD TIMELINE Tags: History, Leadership, Balfour, Resources 1896: Theodor Herzl's publication of Der Judenstaat ("The Jewish State") is widely considered the foundational event of modern Zionism. 1917: The British government adopted the Zionist goal with the Balfour Declaration which views with favor the creation of "a national home for the Jewish people." / Balfour Declaration Feb. 1920: Winston Churchill: "there should be created in our own lifetime by the banks of the Jordan a Jewish State." Apr. 1920: The governments of Britain, France, Italy, and Japan endorsed the British mandate for Palestine and also the Balfour Declaration at the San Remo conference: The Mandatory will be responsible for putting into effect the declaration originally made on November 8, 1917, by the British Government, and adopted by the other Allied Powers, in favour of the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people. July 1922: The League of Nations further confirmed the British Mandate and the Balfour Declaration. 1937: Lloyd George, British prime minister when the Balfour Declaration was issued, clarified that its purpose was the establishment of a Jewish state: it was contemplated that, when the time arrived for according representative institutions to Palestine, / if the Jews had meanwhile responded to the opportunities afforded them ... by the idea of a national home, and had become a definite majority of the inhabitants, then Palestine would thus become a Jewish commonwealth. July 1937: The Peel Commission: 1. "if the experiment of establishing a Jewish National Home succeeded and a sufficient number of Jews went to Palestine, the National Home might develop in course of time into a Jewish State." 2. -

Israel in 1982: the War in Lebanon

Israel in 1982: The War in Lebanon by RALPH MANDEL LS ISRAEL MOVED INTO its 36th year in 1982—the nation cele- brated 35 years of independence during the brief hiatus between the with- drawal from Sinai and the incursion into Lebanon—the country was deeply divided. Rocked by dissension over issues that in the past were the hallmark of unity, wracked by intensifying ethnic and religious-secular rifts, and through it all bedazzled by a bullish stock market that was at one and the same time fuel for and seeming haven from triple-digit inflation, Israelis found themselves living increasingly in a land of extremes, where the middle ground was often inhospitable when it was not totally inaccessible. Toward the end of the year, Amos Oz, one of Israel's leading novelists, set out on a journey in search of the true Israel and the genuine Israeli point of view. What he heard in his travels, as published in a series of articles in the daily Davar, seemed to confirm what many had sensed: Israel was deeply, perhaps irreconcilably, riven by two political philosophies, two attitudes toward Jewish historical destiny, two visions. "What will become of us all, I do not know," Oz wrote in concluding his article on the develop- ment town of Beit Shemesh in the Judean Hills, where the sons of the "Oriental" immigrants, now grown and prosperous, spewed out their loath- ing for the old Ashkenazi establishment. "If anyone has a solution, let him please step forward and spell it out—and the sooner the better. -

'The Left's Views on Israel: from the Establishment of the Jewish State To

‘The Left’s Views on Israel: From the establishment of the Jewish state to the intifada’ Thesis submitted by June Edmunds for PhD examination at the London School of Economics and Political Science 1 UMI Number: U615796 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615796 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 F 7377 POLITI 58^S8i ABSTRACT The British left has confronted a dilemma in forming its attitude towards Israel in the postwar period. The establishment of the Jewish state seemed to force people on the left to choose between competing nationalisms - Israeli, Arab and later, Palestinian. Over time, a number of key developments sharpened the dilemma. My central focus is the evolution of thinking about Israel and the Middle East in the British Labour Party. I examine four critical periods: the creation of Israel in 1948; the Suez war in 1956; the Arab-Israeli war of 1967 and the 1980s, covering mainly the Israeli invasion of Lebanon but also the intifada. In each case, entrenched attitudes were called into question and longer-term shifts were triggered in the aftermath. -

Foreign Terrorist Organizations

Order Code RL32223 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Foreign Terrorist Organizations February 6, 2004 Audrey Kurth Cronin Specialist in Terrorism Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Huda Aden, Adam Frost, and Benjamin Jones Research Associates Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Foreign Terrorist Organizations Summary This report analyzes the status of many of the major foreign terrorist organizations that are a threat to the United States, placing special emphasis on issues of potential concern to Congress. The terrorist organizations included are those designated and listed by the Secretary of State as “Foreign Terrorist Organizations.” (For analysis of the operation and effectiveness of this list overall, see also The ‘FTO List’ and Congress: Sanctioning Designated Foreign Terrorist Organizations, CRS Report RL32120.) The designated terrorist groups described in this report are: Abu Nidal Organization (ANO) Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) Al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade Armed Islamic Group (GIA) ‘Asbat al-Ansar Aum Supreme Truth (Aum) Aum Shinrikyo, Aleph Basque Fatherland and Liberty (ETA) Communist Party of Philippines/New People’s Army (CPP/NPA) Al-Gama’a al-Islamiyya (Islamic Group, IG) HAMAS (Islamic Resistance Movement) Harakat ul-Mujahidin (HUM) Hizballah (Party of God) Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) Jaish-e-Mohammed (JEM) Jemaah Islamiya (JI) Al-Jihad (Egyptian Islamic Jihad) Kahane Chai (Kach) Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK, KADEK) Lashkar-e-Tayyiba -

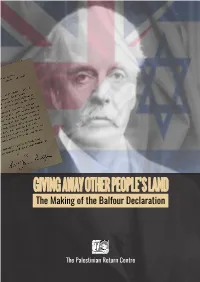

The Making of the Balfour Declaration

The Making of the Balfour Declaration The Palestinian Return Centre i The Palestinian Return Centre is an independent consultancy focusing on the historical, political and legal aspects of the Palestinian Refugees. The organization offers expert advice to various actors and agencies on the question of Palestinian Refugees within the context of the Nakba - the catastrophe following the forced displacement of Palestinians in 1948 - and serves as an information repository on other related aspects of the Palestine question and the Arab-Israeli conflict. It specializes in the research, analysis, and monitor of issues pertaining to the dispersed Palestinians and their internationally recognized legal right to return. Giving Away Other People’s Land: The Making of the Balfour Declaration Editors: Sameh Habeeb and Pietro Stefanini Research: Hannah Bowler Design and Layout: Omar Kachouch All rights reserved ISBN 978 1 901924 07 7 Copyright © Palestinian Return Centre 2017 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publishers or author, except in the case of a reviewer, who may quote brief passages embodied in critical articles or in a review. مركز العودة الفلسطيني PALESTINIAN RETURN CENTRE 100H Crown House North Circular Road, London NW10 7PN United Kingdom t: 0044 (0) 2084530919 f: 0044 (0) 2084530994 e: [email protected],uk www.prc.org.uk ii Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................3