Rajalakshmi Engineering College, Thandalam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Testing the System Page 1 of 4

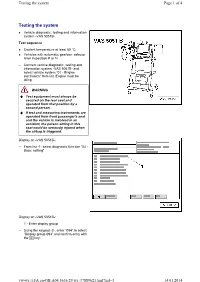

Testing the system Page 1 of 4 Testing the system Vehicle diagnostic, testing and information system -VAS 5051B- Test sequence Coolant temperature at least 80 °C. Vehicles with automatic gearbox: selector lever in position P or N – Connect vehicle diagnostic, testing and information system -VAS 5051B- and select vehicle system “01 - Engine electronics” from list. Engine must be idling. WARNING Test equipment must always be secured on the rear seat and operated from that position by a second person. If test and measuring instruments are operated from front passenger's seat and the vehicle is involved in an accident, the person sitting in this seat could be seriously injured when the airbag is triggered. Display on -VAS 5051B-: – From list -1- select diagnostic function “04 - Basic setting”. Display on -VAS 5051B-: 1 - Enter display group – Using the keypad -2-, enter “094” to select “Display group 094” and confirm entry with the Q key. vw-wi://rl/A.en-GB.A04.5636.29.wi::37889621.xml?xsl=3 14.01.2014 Testing the system Page 2 of 4 – Activate basic setting by touching key A . Display on -VAS 5051B-: – Increase the engine speed to above 2000 rpm for approx. 10 seconds. – Check specifications in display zones -3- and -4-. Display zones 1234 Display group 94: variable valve timing, bank 1 (right-side) and bank 2 (left-side) Display xxxx rpm --- --- --- Readout Engine speed Variable valve timing Variable valve timing Variable valve timing bank 1 bank 2 Range CS-ctrl ON Test OFF Test OFF CS-ctrl OFF Test ON Test ON Syst. -

The Achates Power Opposed-Piston Two-Stroke Engine

Gratis copy for Gerhard Regner Copyright 2011 SAE International E-mailing, copying and internet posting are prohibited Downloaded Wednesday, August 31, 2011 08:49:32 PM The Achates Power Opposed-Piston Two-Stroke 2011-01-2221 Published Engine: Performance and Emissions Results in a 09/13/2011 Medium-Duty Application Gerhard Regner, Randy E. Herold, Michael H. Wahl, Eric Dion, Fabien Redon, David Johnson, Brian J. Callahan and Shauna McIntyre Achates Power Inc Copyright © 2011 SAE International doi:10.4271/2011-01-2221 technical challenges related to emissions, fuel efficiency, cost ABSTRACT and durability - to name a few - and these challenges have Historically, the opposed-piston two-stroke diesel engine set been more easily met by four-stroke engines, as demonstrated combined records for fuel efficiency and power density that by their widespread use. However, the limited availability of have yet to be met by any other engine type. In the latter half fossil fuels and the corresponding rise in fuel cost has led to a of the twentieth century, the advent of modern emissions re-examination of the fundamental limits of fuel efficiency in regulations stopped the wide-spread development of two- internal combustion (IC) engines, and opposed-piston stroke engine for on-highway use. At Achates Power, modern engines, with their inherent thermodynamic advantage, have analytical tools, materials, and engineering methods have emerged as a promising alternative. This paper discusses the been applied to the development process of an opposed- potential of opposed-piston two-stroke engines in light of piston two-stroke engine, resulting in an engine design that today's market and regulatory requirements, the methodology has demonstrated a 15.5% fuel consumption improvement used by Achates Power in applying state-of-the-art tools and compared to a state-of-the-art 2010 medium-duty diesel methods to the opposed-piston two-stroke engine engine at similar engine-out emissions levels. -

Simulation Approaches for the Solution of Cranktrain Vibrations Pavel Novotný, Václav Píštěk, Lubomír Drápal, Aleš Prokop

Simulation Approaches for the Solution of Cranktrain Vibrations PaveL NOVOTNÝ, VÁCLav PíštěK, LUBOMÍR DRÁPAL, ALEš PROKOP 10.2478/v10138-012-0006-8 SIMULATION APPROACHES FOR THE SOLUTION OF CRANKTRAIN VIBRATIONS PAVEL NOVOTNÝ, VÁCLAV PíštěK, LubOMÍR DRÁPAL, ALEš PROKOP Institute of Automotive Engineering, Brno University of Technology, Technická 2896/2, 616 69 Brno, Czech Republic Tel.: +420 541 142 272, Fax: +420 541 143 354, E-mail: [email protected] SHRNUTÍ Vývoj moderních pohonných jednotek vyžaduje využívání pokročilých výpočtových metod, nutných k požadovanému zkrácení času tohoto vývoje společně s minimalizací nákladů na něj. Moderní výpočtové modely jsou stále složitější a umožnují řešit mnoho různých fyzikálních problémů. V případě dynamiky pohonných jednotek a životnosti jejich komponent lze využít několik různých přístupů. Prvním z nich je přístup zahrnující samostatné řešení každého subsystému pohonné jednotky. Druhý přístup využívá model pohonné jednotky obsahující všechny hlavní subsystémy, jako klikový mechanismus, ventilový rozvod, pohon rozvodů nebo vstřikovací čerpadlo, a řeší všechny tyto subsystémy současně i s jejich vzájemným ovlivněním. Cílem článku je pomocí vybraných výsledků prezentovat silné a slabé stránky obou přístupů. Výpočty a experimenty jsou prováděny na traktorovém vznětovém šestiválcovém motoru. KlíčOVÁ SLOVA: POHONNÁ JEDNOTKA, DYNAMIKA, VIBRACE, KLIKOVÝ mechANISMUS, NVH, MKP ABSTRACT The development of modern powertrains requires the use of advanced CAE tools enabling a reduction in engine development times and costs. Modern computational models are becoming ever more complicated and enable integration of many physical problems. Concentrating on powertrain dynamics and component fatigue, a few basic approaches can be used to arrive at a solution. The first approach incorporates a separate dynamics solution of the powertrain parts. -

Lawn-Boy V-Engine Service Manual

LAWN-BOY V-ENGINE SERVICE MANUAL Table of Contents – Page 1 of 2 REFERENCE SECTION SAFETY SPECIFICATIONS - ENGINE SPECIFICATIONS SPECIFICATIONS - ENGINE FASTENER TORQUE REQUIREMENTS SPECIFICATIONS - CARBURETOR SPECIFICATIONS (WALBRO LMR-16) SPECIAL TOOL REQUIREMENTS TROUBLESHOOTING MAINTENANCE SECTION 1 WALBRO LMR-16 CARBURETOR LMR-16 CARBURETOR - IDENTIFICATION LMR-16 CARBURETOR - THEORY OF OPERATION LMR-16 CARBURETOR - GOVERNOR THEORY LMR-16 CARBURETOR - REMOVAL LMR-16 CARBURETOR - DISASSEMBLY LMR-16 CARBURETOR - CLEANING AND INSPECTION LMR-16 CARBURETOR - ASSEMBLY LMR-16 CARBURETOR - PRESETTING THE GOVERNOR LMR-16 CARBURETOR - ASSEMBLING AIR BOX TO CARBURETOR LMR-16 CARBURETOR - INSTALLATION LMR-16 CARBURETOR - FINAL CHECK LMR-16 CARBURETOR - CHOKE ADJUSTMENT LMR-16 CARBURETOR - SERVICING THE AIR FILTER LMR-16 CARBURETOR-TROUBLESHOOTING SECTION 2 PRIMER START CARBURETOR PRIMER START CARBURETOR - IDENTIFICATION PRIMER START CARBURETOR - THEORY OF OPERATION PRIMER START CARBURETOR - GOVERNOR THEORY PRIMER START CARBURETOR - REMOVAL PRIMER START CARBURETOR - DISASSEMBLY PRIMER START CARBURETOR - CLEANING AND INSPECTION PRIMER START CARBURETOR - ASSEMBLY PRIMER START CARBURETOR - INSTALLATION PRIMER START CARBURETOR - PRESETTING THE GOVERNOR PRIMER START CARBURETOR - FINAL CHECK PRIMER START CARBURETOR - SERVICING THE AIR FILTER PRIMER START CARBURETOR TROUBLESHOOTING ENGINE STARTS HARD ENGINE RUNS RICH ENGINE RUNS LEAN FUEL LEAKS FROM CARBURETOR LAWN-BOY V-ENGINE SERVICE MANUAL Table of Contents – Page 2 of 2 SECTION 3 FUEL SYSTEM FUEL -

Wärtsilä 32 PRODUCT GUIDE © Copyright by WÄRTSILÄ FINLAND OY

Wärtsilä 32 PRODUCT GUIDE © Copyright by WÄRTSILÄ FINLAND OY COPYRIGHT © 2021 by WÄRTSILÄ FINLAND OY All rights reserved. No part of this booklet may be reproduced or copied in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, graphic, photocopying, recording, taping or other information retrieval systems) without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. THIS PUBLICATION IS DESIGNED TO PROVIDE AN ACCURATE AND AUTHORITATIVE INFORMATION WITH REGARD TO THE SUBJECT-MATTER COVERED AS WAS AVAILABLE AT THE TIME OF PRINTING. HOWEVER, THE PUBLICATION DEALS WITH COMPLICATED TECHNICAL MATTERS SUITED ONLY FOR SPECIALISTS IN THE AREA, AND THE DESIGN OF THE SUBJECT-PRODUCTS IS SUBJECT TO REGULAR IMPROVEMENTS, MODIFICATIONS AND CHANGES. CONSEQUENTLY, THE PUBLISHER AND COPYRIGHT OWNER OF THIS PUBLICATION CAN NOT ACCEPT ANY RESPONSIBILITY OR LIABILITY FOR ANY EVENTUAL ERRORS OR OMISSIONS IN THIS BOOKLET OR FOR DISCREPANCIES ARISING FROM THE FEATURES OF ANY ACTUAL ITEM IN THE RESPECTIVE PRODUCT BEING DIFFERENT FROM THOSE SHOWN IN THIS PUBLICATION. THE PUBLISHER AND COPYRIGHT OWNER SHALL UNDER NO CIRCUMSTANCES BE HELD LIABLE FOR ANY FINANCIAL CONSEQUENTIAL DAMAGES OR OTHER LOSS, OR ANY OTHER DAMAGE OR INJURY, SUFFERED BY ANY PARTY MAKING USE OF THIS PUBLICATION OR THE INFORMATION CONTAINED HEREIN. Wärtsilä 32 Product Guide Introduction Introduction This Product Guide provides data and system proposals for the early design phase of marine engine installations. For contracted projects specific instructions for planning the installation are always delivered. Any data and information herein is subject to revision without notice. This 1/2021 issue replaces all previous issues of the Wärtsilä 32 Project Guides. Issue Published Updates 1/2021 15.03.2021 Technical data updated. -

Camshaft Deviation Codes.Pdf

AD07.61 -P-4000 -94VA Page 1 of 2 AD07.61-P-4000- Continuous camshaft adjustment - 94VA fault code description ME Angular deviation of camshafts to the crankshaft 1 Fault code 1197 Exhaust camshaft on right cylinder bank, permanent advanced ( Readout on generic scan tool) position (P0017) 1198 Exhaust camshaft on right cylinder bank, permanent retarded position (P0017) 1200 Exhaust camshaft on right cylinder bank, displacement (P0017) 1201 Exhaust camshaft on left cylinder bank, permanent advanced position (P0019) 1202 Exhaust camshaft on left cylinder bank, permanent retarded position (P0019) 1204 Exhaust camshaft on left cylinder bank, displacement (P0019) 1205 Intake camshaft on right cylinder bank, permanent advanced position (P0016) 1206 Intake camshaft on right cylinder bank, permanent retarded position (P0016) 1208 Intake camshaft on right cylinder bank, displacement (P0016) 1209 Intake camshaft on left cylinder bank, permanent advanced position (P0018) 1210 Intake camshaft on left cylinder bank, permanent retarded position (P0018) 1212 Intake camshaft on left cylinder bank, displacement (P0018) 2 Fault storage After expiry of test duration and fault Actuation of engine diagnosis Following two successive driving cycles with faults indicator lamp (EURO4) or CHECK ENGINE (MIL) malfunction indicator lamp 3 Checking frequency Continuous 4 Checked signal or status Comparison of position of the intake camshaft or exhaust camshaft to position of the crankshaft 5 Fault setting conditions 1197, 1201, 1205, 1209 - Permanent advanced position greater than a 20° crank angle 1198, 1202, 1206, 1210 - Permanent retarded position greater than a 20° crank angle 1200, 1204, 1208, 1212 - Fault if after adjustment of a camshaft the new position deviates more than a 9° crank angle from the required value. -

Modernizing the Opposed-Piston, Two-Stroke Engine For

Modernizing the Opposed-Piston, Two-Stroke Engine 2013-26-0114 for Clean, Efficient Transportation Published on 9th -12 th January 2013, SIAT, India Dr. Gerhard Regner, Laurence Fromm, David Johnson, John Kosz ewnik, Eric Dion, Fabien Redon Achates Power, Inc. Copyright © 2013 SAE International and Copyright@ 2013 SIAT, India ABSTRACT Opposed-piston (OP) engines were once widely used in Over the last eight years, Achates Power has perfected the OP ground and aviation applications and continue to be used engine architecture, demonstrating substantial breakthroughs today on ships. Offering both fuel efficiency and cost benefits in combustion and thermal efficiency after more than 3,300 over conventional, four-stroke engines, the OP architecture hours of dynamometer testing. While these breakthroughs also features size and weight advantages. Despite these will initially benefit the commercial and passenger vehicle advantages, however, historical OP engines have struggled markets—the focus of the company’s current development with emissions and oil consumption. Using modern efforts—the Achates Power OP engine is also a good fit for technology, science and engineering, Achates Power has other applications due to its high thermal efficiency, high overcome these challenges. The result: an opposed-piston, specific power and low heat rejection. two-stroke diesel engine design that provides a step-function improvement in brake thermal efficiency compared to conventional engines while meeting the most stringent, DESIGN ATTRIBUTES mandated emissions -

Methods for Heat Analysis and Temperature Field Analysis of the Insulated Diesel

DOE/NASA/0342-1 NASA CR-174783 19950008390 Methods for Heat Analysis and Temperature Field Analysis of the Insulated Diesel Phase I Progress Report Thomas Morel, Paul N. Blumberg, Edward F. Fort, and Rifat Keribar Integral Technologies Incorporated August 1984 Prepared for NATIONAL AERONAUTICSAND SPACEADMIN ISTRATION Lewis Research Center Under Grant DEN 3-342 1[__ _SPf for ! _i _,:_<,:x._ U.S. DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY L&NGLEY RESEARCHCENTER: Conservationand RenewableEnergy LIBRARYN. ASA Office of Vehicle and Engine R&D .AM__TO_".V,RG,_,_ DISCLAIMER This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof. Printed in the United States of America Available from National Technical Information Service U.S. Department of Commerce 5285 Port Royal Road Springfield, VA 22161 NTIS price codes1 Printed copy: A12 Microfiche copy: A01 1Codes are used for pricing all publications. -

Momentum the Volkswagen Group Magazine

momentum The Volkswagen Group magazine NEW BEGINNING A journey into the mobile future momentum New beginning – Journey into the mobile future 3 The Volkswagen Group is transforming itself from one of the largest car manufacturers into a globally leading provider of sustainable mobility. This metamorphosis is already visible in many areas today: new powertrains, strong partnerships for new forms of mobility, and new digital products and services. This issue of momentum brings you stories about people who have set out to drive this change. The journey into the mobile future has begun. 4 Destinations momentum This issue of momentum takes you to places where the Volkswagen Group is working on the future of mobility. The people our authors and photographers met reflect the many answers to one simple question: how will we move in tomorrow’s world? Hong Kong, Midlands, China ― 26 UK ― 32 London, UK ― 42 Mladá Boleslav, Czech Republic ― 80 Stuttgart-Zuffenhausen, Germany ― 70 Sant’Agata Bolognese, Italy ― 78 Bologna, Italy ― 82 Wolfsburg, Germany ― 86 Potsdam, Germany ― 14 Berlin, Germany ― 8, 76 momentum Destinations 5 Södertälje, Barcelona, Sweden Spain ― 48 ― 64 Molsheim, Reykjavík, France ― 52 Munich, Iceland ― 22 Germany ― 84 Bremen, Las Vegas, Germany ― 66 USA ― 38 Oslo, Norway ― 58 6 Contents momentum A question of values ― 8 New demands on mobility On tour with the Crafter ― 22 Anna María Karlsdóttir: through Iceland with the Crafter AILA and me ― 66 Robot lady AILA: real-life machine Symbiosis ― 52 Etienne Salomé, Bugatti: symbiosis between -

Miniature Free-Piston Homogeneous Charge Compression Ignition Engine

Chemical Engineering Science 57 (2002) 4161–4171 www.elsevier.com/locate/ces Miniature free-piston homogeneous charge compression ignition engine-compressor concept—Part I: performance estimation and design considerations unique to small dimensions H. T. Aichlmayr, D. B. Kittelson, M. R. Zachariah ∗ Departments of Mechanical Engineering and Chemistry, The University of Minnesota, 111 Church St. SE, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA Received 18 September 2001; received in revised form 7 February 2002; accepted 18 April 2002 Abstract Research and development activities pertaining to the development of a 10 W, homogeneous charge compression ignition free-piston engine-compressor are presented. Emphasis is placed upon the miniature engine concept and design rationale. Also, a crankcase-scavenged, two-stroke engine performance estimation method (slider-crank piston motion) is developed and used to explore the in;uence of engine operating conditions and geometric parameters on power density and establish plausible design conditions. The minimization of small-scale e=ects such as enhanced heat transfer, is also explored. ? 2002 Published by Elsevier Science Ltd. Keywords: Two-stroke engine; Free-piston engine; Homogeneous charge compression ignition; Microchemical; Performance estimation; Micro-power generation 1. Introduction exist: Enhance batteries or develop miniature energy conver- sion devices. Only modest gains may be expected from the This paper is the ÿrst in a two-part series that presents re- former, consequently the latter is being vigorously pursued sults of recent small-scale engine research and development (Peterson, 2001). In particular, miniature engine-generators e=orts conducted at the University of Minnesota. Speciÿ- (Epstein et al., 1997; Yang et al. 1999; Allen et al., 2001; cally, it introduces the miniature free-piston homogeneous Fernandez-Pello, Liepmann, & Pisano, 2001) are considered charge compression ignition (HCCI) engine-compressor especially promising. -

PDF of Catalog

Edition rd The Power Behind The Power 3 Marine & Industrial Accessories Guide Headquarters New England Carolinas Great Lakes 2365 Route 22, West 48 Leona Drive 4500 Northchase Pkwy., NE 1270 Kyle Court Union, NJ 07083 Middleborough, MA 02346 Wilmington, NC 28405 Wauconda, IL 60084 (908) 964-0700 (508) 946-9200 (910) 792-1900 (847) 526-9700 Fax: (908) 687-6725 Fax: (508) 946-0779 Fax: (910) 792-6266 Fax: (847) 526-9708 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] (800) MAC K-E N G • w w w.m a c k bo ring.c om • (8 00 ) MA C K-FAX TO OUR FRIENDS A Reputation Built On Dependable Service Since 1922 Dear Friends: As we enter into our 84th year in business, we still maintain the core values upon which Mack Boring was founded by our grandfather, Ed McGovern, Sr. Quality, Strong Support, Engineered Solutions, Superior Customer Service, and Added Value to the products we supply, has been the Mack Boring way. Mack Boring and the McGovern Family stand for Quality. We provide quality solutions, backed by quality support – with no compromise, to the challenges our customers face every day, and deliver high quality prod- ucts, services and resources. We hire high quality personnel. Mack Boring relentlessly strives to provide superior support in the form of friendly, technically-savvy customer service representatives in the field, or on the telephone when you call for parts or whole-goods. If you are performing a start-up or an application review, we will support your needs. -

Matching of Internal Combustion Engine

CRANFIELD UNIVERSITY BAPTISTE BONNET MATCHING OF INTERNAL COMBUSTION ENGINE CHARACTERISTICS FOR CONTINUOUSLY VARIABLE TRANSMISSIONS SCHOOL OF ENGINEERING PHD THESIS CRANFIELD UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF ENGINEERING, AUTOMOTIVE DEPARTMENT PHD THESIS BAPTISTE BONNET MATCHING OF INTERNAL COMBUSTION ENGINE CHARACTERISTICS FOR CONTINUOUSLY VARIABLE TRANSMISSIONS SUPERVISOR: PROF. NICHOLAS VAUGHAN 2007 This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor in Philosophy. © Cranfield University, 2007. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without the written permission of the copyright holder . PhD Thesis Abstract ABSTRACT This work proposes to match the engine characteristics to the requirements of the Continuously Variable Transmission [CVT] powertrain. The normal process is to pair the transmission to the engine and modify its calibration without considering the full potential to modify the engine. On the one hand continuously variable transmissions offer the possibility to operate the engine closer to its best efficiency. They benefit from the high versatility of the effective speed ratio between the wheel and the engine to match a driver requested power. On the other hand, this concept demands slightly different qualities from the gasoline or diesel engine. For instance, a torque margin is necessary in most cases to allow for engine speed controllability and transients often involve speed and torque together. The necessity for an appropriate engine matching approach to the CVT powertrain is justified in this thesis and supported by a survey of the current engineering trends with particular emphasis on CVT prospects. The trends towards a more integrated powertrain control system are highlighted, as well as the requirements on the engine behaviour itself.