Communicating Conflict

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Crimes in Crimea

International Crimes in Crimea: An Assessment of Two and a Half Years of Russian Occupation SEPTEMBER 2016 Contents I. Introduction 6 A. Executive summary 6 B. The authors 7 C. Sources of information and methodology of documentation 7 II. Factual Background 8 A. A brief history of the Crimean Peninsula 8 B. Euromaidan 12 C. The invasion of Crimea 15 D. Two and a half years of occupation and the war in Donbas 23 III. Jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court 27 IV. Contextual elements of international crimes 28 A. War crimes 28 B. Crimes against humanity 34 V. Willful killing, murder and enforced disappearances 38 A. Overview 38 B. The law 38 C. Summary of the evidence 39 D. Documented cases 41 E. Analysis 45 F. Conclusion 45 VI. Torture and other forms of inhuman treatment 46 A. Overview 46 B. The law 46 C. Summary of the evidence 47 D. Documented cases of torture and other forms of inhuman treatment 50 E. Analysis 59 F. Conclusion 59 VII. Illegal detention 60 A. Overview 60 B. The law 60 C. Summary of the evidence 62 D. Documented cases of illegal detention 66 E. Analysis 87 F. Conclusion 87 VIII. Forced displacement 88 A. Overview 88 B. The law 88 C. Summary of evidence 90 D. Analysis 93 E. Conclusion 93 IX. Crimes against public, private and cultural property 94 A. Overview 94 B. The law 94 C. Summary of evidence 96 D. Documented cases 99 E. Analysis 110 F. Conclusion 110 X. Persecution and collective punishment 111 A. Overview 111 B. -

The Peninsula of Fear: Chronicle of Occupation and Violation of Human Rights in Crimea

THE PENINSULA OF FEAR: CHRONICLE OF OCCUPATION AND VIOLATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN CRIMEA Kyiv 2016 УДК 341.223.1+342.7.03](477.75)’’2014/2016’’=111 ББК 67.9(4Укр-6Крм)412 Composite authors: Sergiy Zayets (Regional Center for Human Rights), Olexandra Matviychuk (Center for Civil Liberties), Tetiana Pechonchyk (Human Rights Information Center), Darya Svyrydova (Ukrainian Helsinki Human Rights Union), Olga Skrypnyk (Crimean Human Rights Group). The publication contains photographs from public sources, o7 cial websites of the state authorities of Ukraine, the Russian Federation and the occupation authorities, Crimean Field Mission for Human Rights, Crimean Human Rights Group, the online edition Crimea.Realities / Radio Svoboda and other media, court cases materials. ‘The Peninsula of Fear : Chronicle of Occupation and Violation of Human Rights in Crimea’ / Under the general editorship of O. Skrypnyk and T. Pechonchyk. Second edition, revised and corrected. – Kyiv: KBC, 2016. – 136 p. ISBN 978-966-2403-11-4 This publication presents a summary of factual documentation of international law violation emanating from the occupation of the autonomous Republic of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol (Ukraine) by the Russian Federation military forces as well as of the human rights violations during February 2014 – February 2016. The publication is intended for the representatives of human rights organizations, civil activists, diplomatic missions, state authorities, as well as educational and research institutions. УДК 341.223.1+342.7.03](477.75)’’2014/2016’’=111 ББК 67.9(4Укр-6Крм)412 ISBN 978-966-2403-11-4 © S. Zayets, O. Matviychuk, T. Pechonchyk, D. Svyrydova, O. Skrypnyk, 2016 Contents Introduction. -

CRIMEAN ALBUM: Stories of Human Rights Defenders IRYNA VYRTOSU CRIMEAN ALBUM: STORIES of HUMAN RIGHTS DEFENDERS УДК 342.72/.73(477.75-074)(092) К82

IRYNA VYRTOSU CRIMEAN ALBUM: Stories Of Human Rights Defenders IRYNA VYRTOSU CRIMEAN ALBUM: STORIES OF HUMAN RIGHTS DEFENDERS УДК 342.72/.73(477.75-074)(092) К82 Author of text: Iryna Vyrtosu. Editor and author of idea: Tetiana Pechonchyk. Production photographer: Valeriya Mezentseva. Photographers: Mykola Myrnyi, Iryna Kriklya, Olexiy Plisko, as well as photos from the personal archives of the heroes. Transcription of the interviews: Yana Khmelyuk. Translator: Olga Lobastova. Proofreader: Arthur Rogers. Design composition and layout: Pavlo Reznikov. I. Vyrtosu К82 Crimean Album: Stories of Human Rights Defenders / I. Vyrtosu; edit. Т. Pechonchyk; Human Rights Information Centre. – Kyiv: KBC, 2019. – 232 p. ISBN 978-966-2403-16-9 This book contains evidence and memories of Crimean human rights defenders including their work experience before and after the occupation. There are twenty personal stories about the past, present and future of people, who continue to fight for the protection of human rights in Crimea even after losing their home, as well as those, who oppose reprisals living under the occupation. These are stories of Olga Anoshkina, Eskender Bariyev, Mykhailo Batrak, Oleksandra Dvoretska, Abdureshyt Dzhepparov, Lilia Hemedzhy, Sergiy Zayets, Synaver Kadyrov, Emil Kurbedinov, Alyona Luniova, Roman Martynovsky, Ruslan Nechyporuk, Valentyna Potapova, Anna Rassamakhina, Daria Svyrydova, Olga Skrypnyk and Vissarion Aseyev, Iryna Sedova and Oleksandr Sedov, Tamila Tasheva, Maria Sulialina, Volodymyr Chekryhin. The book is intended -

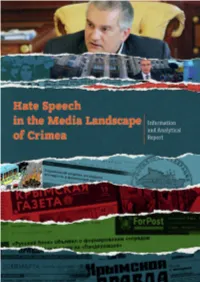

Hate Speech in the Media Landscape of Crimea

HATE SPEECH IN THE MEDIA LANDSCAPE OF CRIMEA AN INFORMATION AND ANALYTICAL REPORT ON THE SPREAD OF HATE SPEECH ON THE TERRITORY OF THE CRIMEAN PENINSULA (MARCH 2014 — JULY 2017) Kyiv — 2018 UDC 32.019.5:323.266:327(477.75+47 0) Authors: Oleksandr Burmahyn Tetiana Pechonchyk Iryna Sevoda Olha Skrypnyk Review: Viacheslav Lykhachev Translation: Anastasiia Morenets Proofreading: Steve Doyle Hate Speech in the Media Landscape of Crimea: An Information and Analytical Report on the Spread of Hate Speech on the Territory of the Crimean Peninsula (March 2014 – July 2017) / under the general editorship of I. Sedova and T. Pechonchyk. – Kyiv, 2018. — 40 p. ISBN 978-966-8977-81-7 This publication presents the outcome of documenting and classifying facts on the use of hate speech on the territory of the occupied Autonomous Republic of Crimea and city of Sevastopol from April 2014 to July 2017. This publication uses material from mass media that have been disseminated in the territory of Crimea since the occupation of the peninsula by the Russian Federation, as well as information from open sources, including information resources from the authorities of Ukraine, Russian Federation and Crimean de-facto authorities, Crimean Human Rights Group and Human Rights Information Centre. This publication is intended for the representatives of state authorities, educational and research institutions, diplomatic missions, international, non-governmental and human rights organizations Crimean Human Rights Group (CHRG) — is an organization of Crimean human rights defenders and journalists aimed at promoting the observance and protection of human rights in Crimea by documenting the violations of human rights and international humanitarian law on the territory of the Crimean peninsula as well as attracting wide attention to these issues and searching for methods and elaborating instruments to defend human rights in Crimea. -

Case Concerning Application of The

INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE CASE CONCERNING APPLICATION OF THE INTERNATIONAL CONVENTION FOR THE SUPPRESSION OF THE FINANCING OF TERRORISM AND OF THE INTERNATIONAL CONVENTION ON THE ELIMINATION OF ALL FORMS OF RACIAL DISCRIMINATION (UKRAINE V. RUSSIAN FEDERATION) VOLUME III OF THE ANNEXES TO THE WRITTEN STATEMENT OF OBSERVATIONS AND SUBMISSIONS ON THE PRELIMINARY OBJECTIONS OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION SUBMITTED BY UKRAINE 14 JANUARY 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS Albin Eser, Mental Elements, in THE ROME STATUTE OF THE INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT (Antonio Cassese et al. eds., OUP 2002) Doug Cassel, Corporate Aiding and Abetting of Human Rights Violations: Confusion in the Courts, Northwestern Journal of International Human Rights, Vol. 6 (2008) Antonio Vallini, Mens Rea: Mistake of Fact and Mistake of Law, in THE OXFORD COMPANION TO INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL JUSTICE (Antonio Cassese ed., 2009) Kai Ambos, Treatise on International Criminal Law, Vol. I: Foundations and General Part (2013) William A. Schabas, The International Criminal Court: A Commentary on the Rome Statute (2d ed., OUP, 2016) Richard Gardiner, TREATY INTERPRETATION (2d ed., 2015) Lee Jarvis & Tim Legrand, The Proscription or Listing of Terrorist Organisations: Understanding, Assessment, and International Comparisons, Terrorism and Political Violence, Vol. 30 (2018) CBS News, “Multiple Kidnappings for Ransom” Funding ISIS, Source Says (21 August 2014) Lingvo Universal Russian-to-English Dictionary, направлять (software ed., 2018) Lingvo Universal Russian-to-English Dictionary, умышленно (software ed., 2018) OHCHR, Report On the Human Rights Situation in Ukraine (16 August to 15 November 2018) U.N. General Assembly Resolution No. 71/205, U.N. Doc. A/RES/71/205, Situation of Human Rights in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and the City of Sevastopol, Ukraine (19 December 2017) 1 U.N. -

Security & Defence

NATIONAL SECURITY & DEFENCE CONTENT π 1-2 (177-178) THE WAR IN DONBAS: REALITIES AND PROSPECTS OF SETTLEMENT ................2 2019 1. GEOPOLITICAL ASPECTS OF CONFLICT IN DONBAS ............................................3 Founded and published by: 1.1. Russia’s “hybrid” aggression: geopolitical dimension ................................................ 3 1.2. Russian intervention in Donbas: goals and specifics .................................................. 6 1.3. Role and impact of the West in settling the conflict in Donbas .................................12 1.4. Ukraine’s policy for Donbas ......................................................................................24 2. OCCUPATION OF DONBAS: CURRENT SITUATION AND TRENDS ........................35 UKRAINIAN CENTRE FOR ECONOMIC & POLITICAL STUDIES 2.1. Military component of Donbas occupation ...............................................................35 NAMED AFTER OLEXANDER RAZUMKOV 2.2. Socio-economic situation in the occupied territories ................................................42 Director General Anatoliy Rachok 2.3. Energy aspect of the conflict in Eastern Ukraine .......................................................50 Editor-in-Chief Yuriy Yakymenko 2.4. Ideology and information policy in “DPR-LPR” .........................................................56 2.5. Environmental situation in the occupied territories ...................................................62 Editor Hanna Pashkova 3. DONBAS: SCENARIOS OF DEVELOPMENTS Halyna Balanovych AND PROSPECTS -

Ukraine Gender Assessment 2014

UKRAINE GENDER ASSESSMENT 2014 August 2014 This report was produced with the financial support of the Govern- ment of Canada. The views and opinions expressed do not neces- sarily reflect the views of the Government of Canada. Ukraine Gender Assessment 2014 Kristin Haffert August 2014 Any opinions, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Foundation for Electoral Systems. Ukraine Gender Assessment 2014 Copyright © 2014 International Foundation for Electoral Systems. All rights reserved. Permission Statement: No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system without the written permission of IFES. Requests for permission should include the following information: • A description of the material for which permission to copy is desired. • The purpose for which the copied material will be used and the manner in which it will be used. • Your name, title, company or organization name, telephone number, fax number, email address and mailing address. Please send all requests for permission to: International Foundation for Electoral Systems 1850 K Street, NW, Fifth Floor Washington, D.C. 20006 Email: [email protected] Fax: 202-350-6701 About IFES The International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES) supports citizens’ right to participate in free and fair elections. Our independent expertise strengthens electoral systems and builds local capacity to deliver sustainable solutions. As the global leader in democracy promotion, we advance good governance and democratic rights by: • Providing technical assistance to election officials • Empowering the underrepresented to participate in the political process • Applying field-based research to improve the electoral cycle Since 1987, IFES has worked in over 135 countries – from developing democracies to mature democracies. -

Crimean Human Rights Situation Review

e-mail: [email protected] website: crimeahrg.org CRIMEAN HUMAN RIGHTS SITUATION REVIEW April 2016 This monitoring review was prepared by the Crimean Human Rights Group on the basis of materials collected in April 2016 Go to link, to see Go to link, to see monthly monitoring reviews of the thematic reviews and articles Crimean Human Rights Group of the Crimean Human Rights Group Crimean Human Rights Situation Review April 2016 CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................2 2. CIVIL AND POLITICAL RIGHTS .....................................................................................................3 Right to liberty and security of the person ..................................................................................3 Detentions ..........................................................................................................................................3 Arrests .................................................................................................................................................4 Searches .............................................................................................................................................4 The right to respect for private life and home ............................................................................5 Progress of the high-profile criminal cases ................................................................................6 Freedom -

Crimean Field Mission on Human Rights Brief Review of the Situation in Crimea

Crimean Field Mission on Human Rights Brief Review of the Situation in Crimea (January 2015) Analytical Review TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ....................................................................................................................................................... 1 І. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................... 2 II. Problems of the residents of Crimea ......................................................................................................................... 3 2.1. Civil and political rights ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Right to Life ................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Right to Freedom and Personal Immunity ................................................................................................................ 3 Disappearance .......................................................................................................................................................... 3 Arrests ........................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Freedom of Speech and Expression ......................................................................................................................... -

Crimean Tatars from Mass Deportation to Hardships in Occupied Crimea

Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal Volume 9 Issue 1 Article 2 6-2015 Full Issue 9.1 Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp Recommended Citation (2015) "Full Issue 9.1," Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal: Vol. 9: Iss. 1: 1-127. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5038/1911-9933.9.1 Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp/vol9/iss1/2 This Front Matter is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ISSN 1911-0359 eISSN 1911-9933 Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal Volume 9.1 - 2015 ii ©2015 Genocide Studies and Prevention 9, no. 1 iii Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp/ Volume 9.1 - 2015 Christian Gudehus, Douglas Irvin-Erickson and Melanie O’Brien Editor’s Introduction .............................................................................................................xx Articles Greta Uehling Genocide’s Aftermath: Neostalinism in Contemporary Crimea ...............................................3 Stephen Blank A Double Dispossession: The Crimean Tatars After Russia’s Ukrainian War ......................18 Karina Korostelina Crimean Tatars From Mass Deportation to Hardships in Occupied Crimea .......................33 Kelly Maddox “Liberat[ing] -

Report on the Human Rights Situation in Ukraine 16 August to 15 November 2016

Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Report on the human rights situation in Ukraine 16 August to 15 November 2016 Contents Paragraphs Page I. Executive Summary ................................................................................................ 1–16 5 II. Right to life, liberty, security and physical integrity ............................................... 17–65 8 A. International humanitarian law in the conduct of hostilities ........................... 17–20 8 B. Casualties ........................................................................................................ 21–26 9 C. Missing persons and recovery of mortal remains ........................................... 27–29 11 D. Summary executions, disappearances, deprivation of liberty, and torture and ill-treatment .............................................................................................. 30–57 12 E. Sexual and gender-based violence .................................................................. 58–65 18 III. Accountability and administration of justice ........................................................... 66–94 20 A. Accountability for human rights violations and abuses in the east ................. 66–74 20 Accountability for abuses committed by the armed groups .................... 66–68 20 Accountability for violations committed by the Ukrainian military or security forces ................................................................................................ 69–74 21 B. Human rights impact -

Right Sector

Not logged in Talk Contributions Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Search Right Sector From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Main page Right Sector (Ukrainian: Правий сектор, Pravyi Contents Sektor) is a far-right Ukrainian nationalist political Right Sector Правий сектор Featured content party that originated in November 2013 as a Current events paramilitary confederation at the Euromaidan Random article protests in Kiev, where its street fighters fought Donate to Wikipedia [7][8] Wikipedia store against riot police. The coalition became a political party on 22 March 2014, at which time it Interaction claimed to have perhaps 10,000 members.[9][10] Help About Wikipedia Founding groups included Trident (Tryzub), led by Slogan God! Ukraine! Freedom![1] Community portal Dmytro Yarosh and Andriy Tarasenko; and the Recent changes Founded November 2013 Ukrainian National Assembly–Ukrainian National Registered 22 May 2014 Contact page Self-Defense (UNA–UNSO), a Merger of Tryzub Tools political/paramilitary organization.[11][12] Other UNA–UNSO What links here Sich founding groups included the Social-National Related changes Former constituents: Social-National Assembly (left in Upload file Assembly and its Patriot of Ukraine paramilitary 2014) Special pages wing, White Hammer, and Carpathian Sich. White White Hammer (expelled in 2014) [13] Permanent link Hammer was expelled in March 2014, and in C14 (left in 2014) Page information the following months Patriot left the organization Headquarters Kiev, Ukraine Wikidata item along with many UNA-UNSO members.[14] Paramilitary Volunteered Ukrainian Corps Cite this page (unofficial) In June 2014 one of the groups was assigned by Print/export Membership 10,000 the Interior Ministry to surveil Mariupol after it Create a book Ideology Ukrainian nationalism Download as PDF captured the city from Russian-backed Ultranationalism[2] [15][16] Printable version insurgents.