Chapter 22 LIBYA:PETROLEUM POTENTIAL of THE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THESIS SEISMICITY of LIBYA and RELATED PROBLEMS Submitted by Hassen A. Hassen Department of Civil Engineering in Partial Fulfill

THESIS SEISMICITY OF LIBYA AND RELATED PROBLEMS Submitted by Hassen A. Hassen Department of Civil Engineering In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Summer, 1983 COLORADO STATE UNIVERSITY Summer, 1983 WE HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER OUR SUPERVISION BY HASSEN A. HASSEN ENTITLED SEISMICITY OF LIBYA AND RELATED PROBLEMS BE ACCEPTED AS FULFILLING IN PART REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE. Committee on Graduate Work Adviser ii ABSTRACT OF THESIS SEISMICITY OF LIBYA AND RELATED PROBLEMS The seismicity of Libya was investigated. Available data of earthquakes, which have occurred in or near Libya during the period 262 A.D. to 1982, have been collected. These data together with geological information are used to investigate the nature of seismic activity and its relationship to the tectonics of the country. Statistical analysis is used to calculate the frequency-magnitude relation for the data in the period from 1963 to 1982. The results indicate that about 140 earthquakes will equal or exceed a Richter magnitude of 5 every 100 years, and one earthquake will equal or exceed a Richter magnitude of 7 every 100 years. The whole country is characterized by low to moderate levels of seismic activity but some segments have experienced large earthquakes in this century and earlier. On the basis of observed and expected seismicity, a four-fold subdivision is suggested defining the activity of the dif ferent parts of the country. The highest activity is found to be concentrated in Cyrenaica (northeastern region) and around the Hun graben (northcentral region). -

Nationwide School Assessment Libya Ministry

Ministry of Education º«∏©àdGh á«HÎdG IQGRh Ministry of Education Nationwide School Assessment Libya Nationwide School Assessment Report - 2012 Assessment Report School Nationwide Libya LIBYA Libya Nationwide School Assessment Report 2012 Libya Nationwide School Assessment Report 2012 º«∏©àdGh á«HÎdG IQGRh Ministry of Education Nationwide School Assessment Libya © UNICEF Libya/2012-161Y4640/Giovanni Diffidenti LIBYA: Doaa Al-Hairish, a 12 year-old student in Sabha (bottom left corner), and her fellow students during a class in their school in Sabha. Doaa is one of the more shy girls in her class, and here all the others are raising their hands to answer the teacher’s question while she sits quiet and observes. The publication of this volume is made possible through a generous contribution from: the Russian Federation, Kingdom of Sweden, the European Union, Commonwealth of Australia, and the Republic of Poland. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the donors. © Libya Ministry of Education Parts of this publication can be reproduced or quoted without permission provided proper attribution and due credit is given to the Libya Ministry of Education. Design and Print: Beyond Art 4 Printing Printed in Jordan Table of Contents Preface 5 Map of schools investigated by the Nationwide School Assessment 6 Acronyms 7 Definitions 7 1. Executive Summary 8 1.1. Context 9 1.2. Nationwide School Assessment 9 1.3. Key findings 9 1.3.1. Overall findings 9 1.3.2. Basic school information 10 1.3.3. -

The Eastern Sirte Basin, Libya

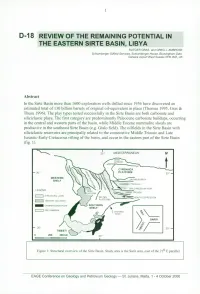

D-18 REVIEW OF THE REMAINING POTENTIAL IN THE EASTERN SIRTE BASIN , LIBYA RUT GE R G RAS a nd DREG J . AMBROSE Scfflumberger O ilfreld Services . Schlumberger House. Buckingham Gate , Gatwíck Airport West Sussex RH6 ONZ, UK A bstract In the Sine Basfin more than 1600 exploration wens drilled since 195 6 have discovered an estimated total of 130 bipion barrels of original all-equivalent in place (Thomas 1995, Gras & Thusu 1996). The play types testel successfully in the Sirte Basfin are botte carbonate and siliciclastic plays. The first category are predominantly Paleocene carbonate buildups, occurring in the tentral and western party of the basin, while Middle Eocene nummulite shoals are praductive in the southeast Sirte Basfin (e .g . Gialo field) . The oilfíelds in the Sine Basfin witte siliciclastic reservoirs are principally related to the consecutive Midfile Triassic and Late .lurassic-Early Cretaceotis rifting of the basin, and occur in the eastern part of the Sirte Basfin (fig. 1 ) . 20 MEDITERRANEAN N ,--'J 777 AK HD A R ~ I T CYRENAICA - d PLATFORM . 3 0 ry v 1 30 W EST ER N B AR H ~~- JAG HBU C S H EL F q~ HAME IM AT TROUGH Dr~ G IAL~-MESS LAH H4GH LE G END r~r n a SAR IR TROUGH G'l ,~T FQRM 0 ST RUCTU RAI IOWS ZEE YEN SOU T H 6F P RFSSIO N PLATFORM T E RTIARY YOL CANICS CAM6RIAN -óft Dl'11-1 CI ,: N SO UTHERN ~ S HE L F SARIR 20 2 0 TIB E STI 0 200 4 00 km 20 Figurc l : 5tructural overview of the Sirte Basfin. -

(Silurian) Anoxic Palaeo-Depressions at the Western Margin of the Murzuq Basin (Southwest Libya), Based on Gamma-Ray Spectrometry in Surface Exposures

GeoArabia, Vol. 11, No. 3, 2006 Gulf PetroLink, Bahrain Identification of early Llandovery (Silurian) anoxic palaeo-depressions at the western margin of the Murzuq Basin (southwest Libya), based on gamma-ray spectrometry in surface exposures Nuri Fello, Sebastian Lüning, Petr Štorch and Jonathan Redfern ABSTRACT Following the melting of the Gondwanan icecap and the resulting postglacial sea- level rise, organic-rich shales were deposited in shelfal palaeo-depressions across North Africa and Arabia during the latest Ordovician to earliest Silurian. The unit is absent on palaeohighs that were flooded only later when the anoxic event had already ended. The regional distribution of the Silurian black shale is now well-known for the subsurface of the central parts of the Murzuq Basin, in Libya, where many exploration wells have been drilled and where the shale represents the main hydrocarbon source rock. On well logs, the Silurian black shale is easily recognisable due to increased uranium concentrations and, therefore, elevated gamma-ray values. The uranium in the shales “precipitated” under oxygen- reduced conditions and generally a linear relationship between uranium and organic content is developed. The distribution of the Silurian organic-rich shales in the outcrop belts surrounding the Murzuq Basin has been long unknown because Saharan surface weathering has commonly destroyed the organic matter and black colour of the shales, making it complicated to identify the previously organic-rich unit in the field. In an attempt to distinguish (previously) organic-rich from organically lean shales at outcrop, seven sections that straddle the Ordovician-Silurian boundary were measured by portable gamma-ray spectrometer along the outcrops of the western margin of the Murzuq Basin. -

Petroleum Generation and Migration in The

Petroleum generation and AUTHORS Ruth Underdown North Africa Research migration in the Ghadames Group, School of Earth, Atmospheric and En- vironmental Sciences, University of Manchester, Basin, north Africa: Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9PL, United Kingdom; [email protected] A two-dimensional Ruth Underdown obtained her first degree in geology from the University of St. Andrews, basin-modeling study Scotland, an M.Sc. degree in petroleum geo- science from Imperial College, London, and a Ph.D. from the University of Manchester, Ruth Underdown and Jonathan Redfern United Kingdom, in 2006, funded by the North Africa Research Group. She is currently teach- ing in the United Kingdom. ABSTRACT Jonathan Redfern North Africa Research The Ghadames Basin contains important oil- and gas-producing res- Group, School of Earth, Atmospheric and En- vironmental Sciences, University of Manchester, ervoirs distributed across Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya. Regional two- Oxford Road, Manchester, M13 9PL, United dimensional (2-D) modeling, using data from more than 30 wells, Kingdom; [email protected] has been undertaken to assess the timing and distribution of hydro- carbon generation in the basin. Four potential petroleum systems Jonathan Redfern obtained his B.Sc. degree in geology from the University of London, Chelsea have been identified: (1) a Middle–Upper Devonian (Frasnian) and College, in 1983, and a Ph.D. from Bristol Uni- Triassic (Triassic Argilo Gre´seux Infe´rieur [TAG-I]) system in the versity, United Kingdom, in 1989. He worked central-western basin; (2) a Lower Silurian (Tannezuft) and Triassic in the oil industry for 12 years, initially with (TAG-I) system to the far west; (3) a Lower Silurian (Tannezuft) and Petrofina in the United Kingdom, southeast Asia, Upper Silurian (Acacus) system in the eastern and northeastern and Libya, and subsequently with Hess. -

Geology and Petroleum Resources of North-Central and Northeastern Africa

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Geology and petroleum resources of north-central and northeastern Africa By James A. Peterson^ Open-File Report 85-709 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards and stratigraphic nomenclature. Reston, Virginia 1985 CONTENTS Page Abstract 1 Int roduct ion 3 Information sources 3 Geography 3 Acknowledgment s 3 Regional geology 7 Structure 7 Stratigraphy and sedimentation 9 Bas ement 2 2 Cambrian - Ordovician 22 Silurian 22 Devonian 22 Carbonif erous 2 3 Permian 23 Tr ias s i c 2 3 Jurassic 23 Cretaceous 24 Te r t iary 25 Quaternary 27 Petroleum geology 27 Sirte Basin 27 Western Sahara region 31 Suez-Sinai 34 Western Desert Basin - Cyrenaica Platform 36 East Tunisia - Pelagian Platform 37 Nile Delta - Nile Basin 39 Resource assessment 43 Procedures 43 Assessment 43 Comments 47 Selected references 49 ILLUSTRATIONS Page Figure 1. North-central and northeastern African assessment regions 4 2. Generalized regional structure map of north-central and northeastern Africa 6 3. Generalized composite subsurface correlation chart, north-central and northeastern Africa 10 4. North-south structural-stratigraphic cross-section A-A', northern Algeria to southeastern Algeria 11 5. East-west structural-stratigraphic cross-section B-B f , west-central Libya to northwestern Egypt 12 6. Northeast-southwest structural-stratigraphic cross-section C-C f , northeastern Tunisia to east-central Algeria 13 7. North-south structural-stratigraphic cross-section D-D f , northeastern Libya to southeastern Libya 14 8. West-east structural-stratigraphic cross-section B'-B f , northern Egypt 15 9. -

Murzuq Rapid Situation Overview Libya, 30 August 2019

Murzuq Rapid Situation Overview Libya, 30 August 2019 BACKGROUND KEY FINDINGS Since early 2019, tensions between the Alahali and Tebu communities in the Libyan city of Murzuq have • Displacement from certain mainly Alahali areas of Murzuq has been widespread, grown progressively more severe, leading to numerous outbreaks of violence. The conflict escalated with only small numbers of residents remaining in these areas. Tebu neighbourhoods to unprecedented levels starting on 4 August 2019, when a series of airstrikes sparked heavy urban also witnessed large-scale, though not complete, displacement, and KIs report that Tebu fighting and mass displacement. As of 27 August, the conflict had eased slightly, but an estimated families are slowly beginning to return to their homes. 1 2 17,320 individuals, or nearly 60% of Murzuq’s population, had fled to cities throughout Libya, leaving • Displacement flows were reportedly determined by a household’s community only small numbers of residents in some areas of the city. identity, with both Alahali and Tebu households fleeing to areas controlled by their own or To inform response plans, between 23 and 27 August, REACH assessed the humanitarian situation allied communities. across seven cities and towns in south Libya that had received large numbers of internally displaced • In several assessed cities, an estimated 15-30% of recent arrivals from Murzuq had persons (IDPs) from Murzuq, as well as conducting two supplementary interviews in Murzuq itself. reportedly moved on to other destinations, most often the city of Sebha. Many of Data was collected through 25 multi-sector key informant (KI) interviews conducted with community these new arrivals had left due to difficulty finding affordable food, shelter, healthcare, and leaders, tribal council members, medical professionals and others. -

Health Sector Field Directory Libya

Libya HEALTH SECTOR FIELD DIRECTORY LIBYA Final edition December 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS NAME OF THE HEALTH SECTOR ORGANIZATION NN 1 ACF (Action Against Hunger) 2 AICS (Italian Agency for Development Cooperation) 3 CEFA (The European committee for training and agriculture) 4 Chemonics International Inc. 5 Emergenza Sorrisi 6 Expertise France 7 GIZ (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit) 8 Handicap International – Humanity & Inclusion 9 Helpcode 10 IFRC (International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies) 11 IMC (International Medical Corps) 12 IOM (International Organization for Migration) 13 IRC (International Rescue Committee) 14 LPFM (Libya Public Financial Management Program) 15 LRC (The Libyan Red Crescent Society) 16 MSF France 17 MSF Holland 18 PUI (Premiere Urgence Internationale) 19 TdH (Terre des Hommes – Italy) 20 The World Bank (WB) 21 UNDP (United Nations Development Programme) 22 UNFPA (United Nations Population Fund) 23 UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees) 24 UNICEF (United Nations Children’s Fund) 25 Voluntas Policy Advisory (Voluntas) 26 WeWorld-GVC 27 WHO (World Health Organization) Action Against Hunger (ACF) Sector: Health/Mental Health Objectives: Continuity of primary health care services • Capacity building of MoH staff • Support to health facilities to improve Infection prevention and control (IPC) • Contribute to the RCCE response with activities focusing at the community level Empowerment of communities and public health services to promote access to quality MHPSS -

The Sirte Basin Province of Libya—Sirte-Zelten Total Petroleum System

The Sirte Basin Province of Libya—Sirte-Zelten Total Petroleum System By Thomas S. Ahlbrandt U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 2202–F U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior Gale A. Norton, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Charles G. Groat, Director Version 1.0, 2001 This publication is only available online at: http://geology.cr.usgs.gov/pub/bulletins/b2202-f/ Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government Manuscript approved for publication May 8, 2001 Published in the Central Region, Denver, Colorado Graphics by Susan M. Walden, Margarita V. Zyrianova Photocomposition by William Sowers Edited by L.M. Carter Contents Foreword ............................................................................................................................................... 1 Abstract................................................................................................................................................. 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 2 Acknowledgments............................................................................................................................... 2 Province Geology................................................................................................................................. 2 Province Boundary.................................................................................................................... -

The Kufrah Paleodrainage System in Libya: a Past Connection to the Mediterranean Sea? Philippe Paillou, Stephen Tooth, S

The Kufrah paleodrainage system in Libya: A past connection to the Mediterranean Sea? Philippe Paillou, Stephen Tooth, S. Lopez To cite this version: Philippe Paillou, Stephen Tooth, S. Lopez. The Kufrah paleodrainage system in Libya: A past connection to the Mediterranean Sea?. Comptes Rendus Géoscience, Elsevier Masson, 2012, 344 (8), pp.406-414. 10.1016/j.crte.2012.07.002. hal-00833333 HAL Id: hal-00833333 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00833333 Submitted on 12 Jun 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. *Manuscript / Manuscrit The Kufrah Paleodrainage System in Libya: 1 2 3 A Past Connection to the Mediterranean Sea ? 4 5 6 7 8 9 Le système paléo-hydrographique de Kufrah en Libye : 10 11 12 Une ancienne connexion avec la mer Méditerranée ? 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Philippe PAILLOU 21 22 Univ. Bordeaux, LAB,UMR 5804, F-33270, Floirac, France 23 24 Tel: +33 557 776 126 Fax: +33 557 776 110 25 26 27 E-mail: [email protected] 28 29 30 31 32 Stephen TOOTH 33 34 Institute of Geography and Earth Sciences, Aberystwyth University, Ceredigion, UK 35 36 37 38 39 Sylvia LOPEZ 40 41 42 Univ. -

Health Response to COVID-19 in Libya WHO Update # 12 Reporting Period

Health response to COVID-19 in Libya WHO update # 12 Reporting period: 23 July to 5 August 2020 1 | P a g e 2 | P a g e Highlights o Under WHO’s transmission scenarios, Libya’s status has been revised from “clusters of cases” to “community transmission”. A total of 4224 people in Libya have been infected with COVID-19. Of this number, 3495 people remain actively infected, 633 people have recovered, and 93 people have died. (This translates to 614 confirmed cases and 13 deaths per 1 million population.) The national case fatality rate is 2.27%. o The municipalities reporting a significant increase are Tripoli, Misrata, Sebha, Zliten Ashshatti, Benghazi, Ubari, Janzour and Zawiya. o Thus far, a total of 68 027 specimens have been tested. This number includes 38 784 in Tripoli, 14 045 in Benghazi, 8604 in Misrata and 5389 in Sebha. o Nationwide, there are severe shortages of GeneXpert cartridges and laboratory reagents used for virus extraction. o On 31 July 2020, the Government of National Accord (GNA) declared a five-day lockdown starting the same day. o Misrata is emerging as a hotspot. The city has the second largest number of people infected with COVID-19. Collaboration with national authorities o On 4 August 2020, the Libyan Ambassador to the United Nations met WHO’s Director-General to discuss the evolving COVID-19 situation and request increased support from WHO. o WHO is continuing to brief Ambassadors to Libya on the COVID-19 situation and the challenges faced by WHO in its efforts to support the national response. -

Dissertation Isotope and Noble Gas Study of Three

DISSERTATION ISOTOPE AND NOBLE GAS STUDY OF THREE AQUIFERS IN CENTRAL AND SOUTHEAST LIBYA Submitted by Mohamed S. E. Al Faitouri Department of Geosciences In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Summer 2013 Doctoral Committee: Advisor: William Sanford Michael Ronayne Steven Fassnacht Reagan Waskom Copyright by Mohamed S. E. Al Faitouri 2013 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT ISOTOPE AND NOBLE GAS STUDY OF THREE AQUIFERS IN CENTRAL AND SOUTHEAST LIBYA Libya suffers from a shortage in water resources due to its arid climate. The annual precipitation in Libya is less than 200 mm in the narrow coastal plain, while the southern part of the country receives less than 1mm. On the other hand, Libya has large resources of good quality groundwater distributed in six basin systems beneath the Sahara. In 1983, the Libyan government established the Great Man-Made River Authority (GMRA) in order to transport 6.5 million cubic meters a day of this groundwater to the coastal cities, where over 90% of the population lives. This large water extraction of one million cubic meters per day (or greater) from each wellfield has the potential to greatly stress the water resources in these areas. This study focuses on three GMRA wellfields in two sedimentary basins (Sirt and Al Kufra) in central and southeast Libya. The Sarir wellfield is located within the Sirt basin and consists of 126 production wells; the Tazerbo wellfield in the Al Kufra basin has 108 wells; and the proposed Al Kufra wellfield is also in the Al Kufra Basin and will have 300 production wells.