Interview of Jerry Mcdowell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gigabit Ethernet - CH 3 - Ethernet, Fast Ethernet, and Gigabit Ethern

Switched, Fast, and Gigabit Ethernet - CH 3 - Ethernet, Fast Ethernet, and Gigabit Ethern.. Page 1 of 36 [Figures are not included in this sample chapter] Switched, Fast, and Gigabit Ethernet - 3 - Ethernet, Fast Ethernet, and Gigabit Ethernet Standards This chapter discusses the theory and standards of the three versions of Ethernet around today: regular 10Mbps Ethernet, 100Mbps Fast Ethernet, and 1000Mbps Gigabit Ethernet. The goal of this chapter is to educate you as a LAN manager or IT professional about essential differences between shared 10Mbps Ethernet and these newer technologies. This chapter focuses on aspects of Fast Ethernet and Gigabit Ethernet that are relevant to you and doesn’t get into too much technical detail. Read this chapter and the following two (Chapter 4, "Layer 2 Ethernet Switching," and Chapter 5, "VLANs and Layer 3 Switching") together. This chapter focuses on the different Ethernet MAC and PHY standards, as well as repeaters, also known as hubs. Chapter 4 examines Ethernet bridging, also known as Layer 2 switching. Chapter 5 discusses VLANs, some basics of routing, and Layer 3 switching. These three chapters serve as a precursor to the second half of this book, namely the hands-on implementation in Chapters 8 through 12. After you understand the key differences between yesterday’s shared Ethernet and today’s Switched, Fast, and Gigabit Ethernet, evaluating products and building a network with these products should be relatively straightforward. The chapter is split into seven sections: l "Ethernet and the OSI Reference Model" discusses the OSI Reference Model and how Ethernet relates to the physical (PHY) and Media Access Control (MAC) layers of the OSI model. -

IN the UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT for the DISTRICT of DELAWARE in Re: ) Chapter 11 ) NORTEL NETWORKS INC., Et Al. ) Case No

IN THE UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF DELAWARE In re: ) Chapter 11 ) NORTEL NETWORKS INC., et al. ) Case No. 09-10138(KG) ) (Jointly Administered) Debtors. ) Re Dkt. No. 18210 SNMP Research International, Inc. and ) SNMP Research, Inc., ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) v. ) Adv. Proc. No. 11-53454(KG) ) Nortel Networks Inc., et al., ) ) Defendants. ) Re Dkt. No. 585 OPINION MORRIS, NICHOLS, ARSHT & TUNNELL LLP CLEARY GOTTLIEB STEEN & HAMILTON LLP Derek C. Abbott, Esquire Lisa M. Schweitzer, Esquire Andrew R. Remming, Esquire David H. Herrington, Esquire Tamara K. Minott, Esquire One Liberty Plaza Andrew J. Roth-Moore, Esquire New York, New York 10006 1201 North Market Street P.O. Box 1347 Wilmington, Delaware 19801 - Counsel for Debtors and Debtors in Possession – COLE SCHOTZ P.C. KING & BALLOW LAW OFFICES Norman L. Pernick, Esquire Richard S. Busch, Esquire Nicholas J. Brannick, Esquire 315 Union Street, Suite 1100 500 Delaware Avenue, Suite 1410 Nashville, TN 37201 Wilmington, DE 19801 COLE SCHOTZ P.C. EGERTON, MCAFEE, ARMISTEAD G. David Dean, Esquire & DAVIS, P.C. 300 E. Lombard Street, Suite 1450 John L. Wood, Esq. Baltimore, MD 21202 900 S. Gay Street Knoxville, TN 37902 - Counsel for SNMP Research, Inc. and SNMP Research International, Inc. - I. INTRODUCTION1 The litigants in the adversary proceeding are plaintiffs SNMP Research International, Inc. (“SNMPRI”) and SNMP Research, Inc. (“SNMPR”) (collectively, “SNMP”) and the defendants, Nortel Networks Inc. and affiliated entities (“Nortel”). The Court held a two-day trial on May 11 and 12, 2017 (the “Trial”) to determine whether certain software was licensed for use or distribution by Nortel with respect to products after June 20, 2003. -

CV, Curriculum Vitae, Rhys Haden

Curriculum Vitae Last Updated 2nd February 2016 Rhys Bradley Haden Personal Information Address Telephone E-mail Website Available on Available on [email protected] http://rhyshaden.com enquiry enquiry Date of Birth Nationality Status Driver 30th July 1963 British Married with two children Full clean UK license Key Skills Structured Cabling Design and installation. Integration of building services on to a common data infrastructure. Intelligent Patching Systems design and installation. PC construction. HTML authoring and web site design. Good grounding in Windows network design and installation. Thorough knowledge of TCP/IP addressing, subnetting and summarisation. Solid understanding of IP protocols including HTTP, FTP, Telnet etc. Ethernet, Token Ring and FDDI design and troubleshooting within both shared and switched LAN environments. Thorough knowledge of bridging in both Ethernet and Token Ring environments. Experience in the use of network analysis tools in troubleshooting LANs. ISDN, SMDS, Frame Relay and ATM knowledge and experience, including some LANE. Good routing protocol experience including RIP (1 and 2), OSPF, EIGRP and HSRP/VRRP. Some BGP experience. Good Novell IPX protocol experience. Some DECnet protocol experience. Thorough Nortel Networks equipment experience particularly on the router side. Good experience of designing using, and working with, Extreme Network switches. Thorough knowledge of most of Cisco Systems network equipment range routers, switches and security. Cisco firewall configuration and management. Some experience in IPsec VPN set up. Substantial experience in Content Delivery networks, layer 4-7 switching and HTTP cache engines. Some Experience in IP Telephony and Voice over IP, within the Cisco environment. Wireless LAN design skills. Good teaching skills, including some presentation ability and positive customer- facing attitude. -

Test Results of Nortel and Lucent Units

802.3af Plug Fest Results IEEE November 2000 Plenary Michael McCormack Tampa Units Tested: 1. Nortel unit with two D-Cell power supply 2. Lucent unit with AC power supply Test Method: 1. Verify operation of unit with provided “dummy load” and 1M CAT5 patch cord 2. Plug unit under test into legacy port with 1M CAT5 patch cord 3. Repeat step 2 with all legacy equipment within reach 4. Plug unit under test into legacy port with 1M “Twisted” CAT5 patch cord 5. Repeat step 4 with all legacy equipment within reach 6. Verify operation of unit with provided “dummy load” and 1M CAT5 patch cord Switches / Hubs / Routers MFG Model Problem Liteon LiteSpeed 100 Level One LXD 980 Digital Etherworks 2TTX Edge Access (Canoga Perkins) 9135 Switch Samsung SS6224S Fore ForeRunnere ES-3810 Intel 16 Port 10/100 Hub SynOptics (Bay Networks) 28115 SMC EZ Hub 100 5208TX Intel 6000 Series Intel Express 410F Nortel Networks Falcon 24T Nortel Networks BayStack 450-24T Anritsu Multiflow 5024 Bay Networks Model 5000 (5625 Blade) Intel 330T Stackable Hub Intel Express 550 (4Port Uplink Mod) Intel EtherExpress 10/100 Stackable Hub 802.3af Plug Fest Results IEEE November 2000 Plenary Michael McCormack Tampa Switches / Hubs / Routers MFG Model Problem Intel Express 100Base-TX Stackable Hub Intel Express 100Base-TX Switching Hub Intel Express 510T Intel Express 220T Intel Express 520T SMC Tiger Stack 3312TC SMC TigerStack 100 5324TX SMC TigerStack 100 5300-NMU SMC TigerStack 100 5312TX SMC TigerHub 100 SMC (Cabletron) Tiger Switch (Fast Net 10) Extreme Summit 48-I SMC -

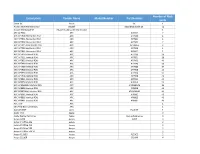

Smartzone 7.1 Device Catalog

Number of Rack Description Vendor Name Model Number Part Number Units 3com 8C 3com 8C 1 Alcatel 3600 Mainstreet 23 Alcatel 3600 Mainstreet 23_ 11 Alcatel Omnistack-24 Alcatel Sistemas de Informacion 1 APC ACF002 APC ACF002 2 APC AP7900 Horizontal PDU APC AP7900 1 APC AP7901 Horizontal PDU APC AP7901 1 APC AP7902 Horizontal PDU APC AP7902 2 APC AP7911A Horizontal PDU APC AP7911A 2 APC AP7920 Horizontal PDU APC AP7920 1 APC AP7921 Horizontal PDU APC AP8921 1 APC AP7930 Vertical PDU APC AP7930 36 APC AP7931 Vertical PDU APC AP7931 28 APC AP7932 Vertical PDU APC AP7932 40 APC AP7940 Vertical PDU APC AP7940 36 APC AP7960 Vertical PDU APC AP7960 37 APC AP7968 Vertical PDU APC AP7968 40 APC AP7990 Vertical PDU APC AP7990 37 APC AP7998 Vertical PDU APC AP7998 40 APC AP8941 Vertical PDU APC AP8941 42 APC AP8958 Vertical PDU APC AP8958 23 APC AP8958NA3 Vertical PDU APC AP8958NA3 23 APC AP8959 Vertical PDU APC AP8959 40 APC AP8959NA3 Vertical PDU APC AP8959NA3 40 APC AP8961 Vertical PDU APC AP8961 40 APC AP8965 Vertical PDU APC AP8965 40 APC AP8981 Vertical PDU APC AP8981 41 APC PDU APC 1 APC PDU Environmentals APC 1 Apex El 40DT Apex El_40DT 1 Apple iPad Apple 0 Apple Xserve Raid array Apple Xserve Raid array 3 Avaya G350 Avaya G350 3 Avaya IP Office 406 Avaya 2 Avaya IP Office 412 Avaya 2 Avaya IP Office 500 Avaya 2 Avaya IP Office 500 V2 Avaya 2 Avaya P133G2 Avaya P133G2 2 Avaya S3210R Avaya S3210R 4 Number of Rack Description Vendor Name Model Number Part Number Units Avaya S8500C Avaya S8500C 1 Avaya S8720 Avaya S8720 2 Nortel 8610 Avaya (Rapid -

ETHERNET TECNOLOGIES 1º: O Que É Ethernet ?

ETHERNET TECNOLOGIES 1º: O Que é Ethernet ? Ethernet Origem: Wikipédia, a enciclopédia livre. Este artigo ou se(c)ção cita fontes fiáveis e independentes, mas que não cobrem todo o conteúdo (desde setembro de 2012). Por favor, adicione mais referências e insira-as no texto ou no rodapé, conforme o livro de estilo. Conteúdo sem fontes poderá serremovido. Encontre fontes: Google (notícias, livros, acadêmico) — Yahoo! — Bing. Protocolos Internet (TCP/IP) Cam Protocolo ada 5.Apl HTTP, SMTP, FTP, SSH,Telnet, SIP, RDP, I icaçã RC,SNMP, NNTP, POP3, IMAP,BitTorrent, o DNS, Ping ... 4.Tra nspo TCP, UDP, RTP, SCTP,DCCP ... rte 3.Re IP (IPv4, IPv6) , ARP, RARP,ICMP, IPsec ... de Ethernet, 802.11 (WiFi),802.1Q 2.Enl (VLAN), 802.1aq ace (SPB), 802.11g, HDLC,Token ring, FDDI,PPP,Switch ,Frame relay, 1.Físi Modem, RDIS, RS-232, EIA-422, RS-449, ca Bluetooth, USB, ... Ethernet é uma arquitetura de interconexão para redes locais - Rede de Área Local (LAN) - baseada no envio de pacotes. Ela define cabeamento e sinais elétricos para a camada física, e formato de pacotes e protocolos para a subcamada de controle de acesso ao meio (Media Access Control - MAC) do modelo OSI.1 A Ethernet foi padronizada pelo IEEE como 802.3. A partir dos anos 90, ela vem sendo a tecnologia de LAN mais amplamente utilizada e tem tomado grande parte do espaço de outros padrões de rede como Token Ring, FDDI e ARCNET.1 Índice [esconder] 1 História 2 Descrição geral 3 Ethernet com meio compartilhado CSMA/CD 4 Hubs Ethernet 5 Ethernet comutada (Switches Ethernet) 6 Tipos de -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent N0.: US 8,155,012 B2 Austermann, III Et A1

US008155012B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent N0.: US 8,155,012 B2 Austermann, III et a1. (45) Date of Patent: Apr. 10, 2012 (54) SYSTEM AND METHOD FOR ADAPTING A FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS PIECE OF TERMINAL EQUIPMENT DE 3907652 A1 9/1990 (75) Inventors: John F. Austermann, III, Huntington (Continued) Woods, MI (US); Marshall B. Cummings, Troy, MI (U S) OTHER PUBLICATIONS (73) Assignee: ChriMar Systems, Inc., Farmington Entertainment Services and Technology Association (ESTA)iRec Hills, MI (US) ommended Practice for Ethernet Cabling Systems in Entertainment Lighting Applications [44 pages] (1996). ( * ) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this patent is extended or adjusted under 35 (Continued) U.S.C. 154(b) by 331 days. Primary Examiner * Chi Pham (21) Appl. No.: 12/239,001 Assistant Examiner * Soon-Dong Hyun Filed: Sep. 26, 2008 (74) Attorney, Agent, or Firm * Harness, Dickey & Pierce, (22) P.L.C. (65) Prior Publication Data US 2009/0022057 A1 Jan. 22, 2009 (57) ABSTRACT In accordance with the teachings of the present invention, a Related US. Application Data communication system (17) is provided for generating and (63) Continuation of application No. 10/ 668,708, ?led on monitoring data over pre-existing conductors (2A-2D) Sep. 23, 2003, now Pat. No. 7,457,250, which is a between associated pieces of networked computer equipment continuation of application No. 09/370,430, ?led on (3A-3D). The system includes a communication device (16) Aug. 9, 1999, now Pat. No. 6,650,622, which is a attached to the electronic equipment that transmits informa continuation-in-part of application No. -

Network Monitoring Using Extreme Visualization Performance and Fault Manager Plus

Network Monitoring using Extreme Visualization Performance and Fault Manager Plus Release 1.1 NN48100-500 Issue 02.02 December 2017 © 2017, Extreme Networks, Inc. REPRESENT THAT YOU HAVE THE AUTHORITY TO BIND SUCH All Rights Reserved. ENTITY TO THESE TERMS OF USE. IF YOU DO NOT HAVE SUCH AUTHORITY, OR IF YOU DO NOT WISH TO ACCEPT THESE Notice TERMS OF USE, YOU MUST NOT ACCESS OR USE THE While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that the HOSTED SERVICE OR AUTHORIZE ANYONE TO ACCESS OR information in this document is complete and accurate at the time of USE THE HOSTED SERVICE. printing, Extreme Networks, Inc. assumes no liability for any errors. Licenses Extreme Networks, Inc. reserves the right to make changes and corrections to the information in this document without the obligation THE SOFTWARE LICENSE TERMS AVAILABLE ON THE to notify any person or organization of such changes. EXTREME NETWORKS WEBSITE, https://extremeportal.force.com OR SUCH SUCCESSOR SITE AS DESIGNATED BY EXTREME Documentation disclaimer NETWORKS, ARE APPLICABLE TO ANYONE WHO “Documentation” means information published in varying mediums DOWNLOADS, USES AND/OR INSTALLS EXTREME NETWORKS which may include product information, operating instructions and SOFTWARE, PURCHASED FROM EXTREME NETWORKS INC., performance specifications that are generally made available to users ANY EXTREME NETWORKS AFFILIATE, OR AN EXTREME of products. Documentation does not include marketing materials. NETWORKS CHANNEL PARTNER (AS APPLICABLE) UNDER A Extreme Networks shall not be responsible for any modifications, COMMERCIAL AGREEMENT WITH EXTREME NETWORKS OR additions, or deletions to the original published version of AN EXTREME NETWORKS CHANNEL PARTNER. -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,942,107 B2 Austerman, III Et Al

USOO8942107B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,942,107 B2 Austerman, III et al. (45) Date of Patent: Jan. 27, 2015 (54) PIECE OF ETHERNETTERMINAL USPC ......................... 370/241; 370/463: 340/568.1 EQUIPMENT (58) Field of Classification Search None (75) Inventors: John F. Austerman, III, Huntington See application file for complete search history. Woods, MI (US); Marshall B. Cummings, Troy, MI (US) (56) References Cited (73) Assignee: ChriMar Systems, Inc., Farmington U.S. PATENT DOCUMENTS Hills, MI (US) 202,495 A 4, 1878 Watson (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this 244,426 A 7, 1881 Bell patent is extended or adjusted under 35 (Continued) U.S.C. 154(b) by 0 days. FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS (21) Appl. No.: 13/370,918 CA 21831.06 A1 2, 1998 (22) Filed: Feb. 10, 2012 CN 2050662 U. 1, 1990 (Continued) (65) Prior Publication Data OTHER PUBLICATIONS US 2012/0250784A1 Oct. 4, 2012 “10BaseT Takes Off” (LAN Magazine, May 1991). Related U.S. Application Data (Continued) (63) Continuationsep. 26, 2008, of now application Pat. No. No. 8,155.012, 12/239,001, which filed is on a Primary Examiner Chi HPham continuation of application No. 10/668,708, filed on Assistant Examiner — Soon-Dong D Hyun Sep. 23, 2003, now Pat. No. 7,457.250, which is a (74) Attorney, Agent, or Firm — Harness, Dickey & Pierce, continuation of application No. 09/370.430, filed on P.L.C. Aug. 9, 1999, now Pat. No. 6,650,622, which is a continuation-in-part of application No. -

Bay Networks a Class Merger Problems Assignment See Case, Bay Networks B

15.387 – Entrepreneurial Sales Case Bay Networks A Class Merger Problems Assignment See case, Bay Networks B Overview: Paul Severino, CEO of Wellfleet Communications, called Gary Beach, his Senior Vice President of Sales into his office. “Well, Big Guy, it’s done – we finished the merger agreement with Synoptics last night. That’s the Good News.” “Any time you start off telling me good news, I know that there is another shoe to drop – what is it?” said Beach. “Ah… we have been together for a long time and you know me so well…so...you have the job of integrating the sales forces…and we have to do it quickly, we have to do it fairly, we have to have as little disruption with our customers as possible, and we have to do it worldwide. And we have to do it in 100 days – what’s your first inclination?” said Severino. “Quit!” smiled Beach. “Not an option!” said Severino…”And by the way, you have to make sure that sales for both companies continues during this transition. Remember, we have been the number one company in the stock exchange the past two years… so everyone is expecting the stock price will stay up there.” “Does our new company have a name?” asked Beach. “How does ‘Bay Networks’ hit you? We are in Billerica, Mass and they are in Santa Clara – and we each have a bay – of course they are 3000 miles apart… and we haven’t decided on where the headquarters should be. But I have more good news – American Airlines now has three non-stops a day from Boston to the San Jose airport! And three non-stops the other way!” “Why don’t we just make our headquarters in the air at 30,000 feet?” said Beach. -

DTE Power Via MDI Discovery Process

'7(3RZHUYLD0', 'LVFRYHU\3URFHVV G. Vergnaud / R. Gass / R. Jaeger ALCATEL [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] DTE Power via MDI analysis ALCATEL BUSINESS SYSTEMS G. Vergnaud, R. Gass, R. Jaeger Page 1 Economic and technical feasibility : PD side ▼ Three types of such terminations : L L To remote To remote power C2 C1 power C1 source source DC/DC Converter DC/DC Converter To local power Case 1: terminal without local power source Case 2- terminal with local power & basic protection To remote L power & Case 3- terminal with local power & source C1 protection including possible reverse polarity of the remote power DC/DC Converter To local power ▼ C1 is the capacitor naturally present at terminal DC/DC converter input ▼ Only one requirement C2 ≥ 200nF DTE Power via MDI analysis ALCATEL BUSINESS SYSTEMS G. Vergnaud, R. Gass, R. Jaeger Page 2 Economic and technical feasibility : PSE side (block diagram) AC open Function needed for circuit discovery process detector AC discovery voltage control AC discovery 5kHz/1Vppvoltage injector DC open circuit detector DC discovery voltage control DC discovery -5V voltage injector From/To FPGA (State machine) From Ethernet physical chip To Link/Terminal Optional insulation (Environment B requirement) Over current -5V detector Power control & Fault Detection -48V Current Power control limiter DTE Power via MDI analysis ALCATEL BUSINESS SYSTEMS G. Vergnaud, R. Gass, R. Jaeger Page 3 Economic and technical feasibility : PSE side (mock-up used for tests) Alternative voltage injector AC open circuit R1 detector DC open circuit detector Low direct voltage injector R2 DTE Power via MDI analysis ALCATEL BUSINESS SYSTEMS G. -

Ethernet - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Página 1 De 12

Ethernet - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Página 1 de 12 Ethernet From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The five-layer TCP/IP model Ethernet is a family of frame-based computer 5. Application layer networking technologies for local area networks (LANs). The name comes from the physical concept of DHCP · DNS · FTP · Gopher · HTTP · the ether. It defines a number of wiring and signaling IMAP4 · IRC · NNTP · XMPP · POP3 · standards for the physical layer, through means of SIP · SMTP · SNMP · SSH · TELNET · network access at the Media Access Control RPC · RTCP · RTSP · TLS · SDP · (MAC)/Data Link Layer, and a common addressing SOAP · GTP · STUN · NTP · (more) format. 4. Transport layer Ethernet is standardized as IEEE 802.3. The TCP · UDP · DCCP · SCTP · RTP · combination of the twisted pair versions of Ethernet for RSVP · IGMP · (more) connecting end systems to the network, along with the 3. Network/Internet layer fiber optic versions for site backbones, is the most IP (IPv4 · IPv6) · OSPF · IS-IS · BGP · widespread wired LAN technology. It has been in use IPsec · ARP · RARP · RIP · ICMP · from the 1990s to the present, largely replacing ICMPv6 · (more) competing LAN standards such as token ring, FDDI, 2. Data link layer and ARCNET. In recent years, Wi-Fi, the wireless LAN 802.11 · 802.16 · Wi-Fi · WiMAX · standardized by IEEE 802.11, is prevalent in home and ATM · DTM · Token ring · Ethernet · small office networks and augmenting Ethernet in FDDI · Frame Relay · GPRS · EVDO · larger installations. HSPA · HDLC · PPP · PPTP · L2TP · ISDN