Finding the Divine in Drag Performance Richard Andrew Curtiss Brigham Young University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Corneliailie

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/289370357 Talk Shows Article · December 2006 DOI: 10.1016/B0-08-044854-2/00357-6 CITATIONS READS 24 4,774 1 author: Cornelia Ilie Malmö University 57 PUBLICATIONS 476 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Parenthetically Speaking: Parliamentary Parentheticals as Rhetorical Strategies View project All content following this page was uploaded by Cornelia Ilie on 09 December 2018. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Provided for non-commercial research and educational use only. Not for reproduction or distribution or commercial use This article was originally published in the Encyclopedia of Language & Linguistics, Second Edition, published by Elsevier, and the attached copy is provided by Elsevier for the author's benefit and for the benefit of the author's institution, for non- commercial research and educational use including without limitation use in instruction at your institution, sending it to specific colleagues who you know, and providing a copy to your institution’s administrator. All other uses, reproduction and distribution, including without limitation commercial reprints, selling or licensing copies or access, or posting on open internet sites, your personal or institution’s website or repository, are prohibited. For exceptions, permission may be sought for such use through Elsevier's permissions site at: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/permissionusematerial Ilie C (2006), Talk Shows. In: Keith Brown, (Editor-in-Chief) Encyclopedia of Language & Linguistics, Second Edition, volume 12, pp. 489-494. Oxford: Elsevier. Talk Shows 489 Talk Shows C Ilie,O¨ rebro University, O¨ rebro, Sweden all-news radio programs, which were intended as ß 2006 Elsevier Ltd. -

Bianca Del Rio Floats Too, B*TCHES the ‘Clown in a Gown’ Talks Death-Drop Disdain and Why She’S Done with ‘Drag Race’

Drag Syndrome Barred From Tanglefoot: Discrimination or Protection? A Guide to the Upcoming Democratic Presidential Kentucky Marriage Battle LGBTQ Debates Bianca Del Rio Floats Too, B*TCHES The ‘Clown in a Gown’ Talks Death-Drop Disdain and Why She’s Done with ‘Drag Race’ PRIDESOURCE.COM SEPT.SEPT. 12, 12, 2019 2019 | | VOL. VOL. 2737 2737 | FREE New Location The Henry • Dearborn 300 Town Center Drive FREE PARKING Great Prizes! Including 5 Weekend Join Us For An Afternoon Celebration with Getaways Equality-Minded Businesses and Services Free Brunch Sunday, Oct. 13 Over 90 Equality Vendors Complimentary Continental Brunch Begins 11 a.m. Expo Open Noon to 4 p.m. • Free Parking Fashion Show 1:30 p.m. 2019 Sponsors 300 Town Center Drive, Dearborn, Michigan Party Rentals B. Ella Bridal $5 Advance / $10 at door Family Group Rates Call 734-293-7200 x. 101 email: [email protected] Tickets Available at: MiLGBTWedding.com VOL. 2737 • SEPT. 12 2019 ISSUE 1123 PRIDE SOURCE MEDIA GROUP 20222 Farmington Rd., Livonia, Michigan 48152 Phone 734.293.7200 PUBLISHERS Susan Horowitz & Jan Stevenson EDITORIAL 22 Editor in Chief Susan Horowitz, 734.293.7200 x 102 [email protected] Entertainment Editor Chris Azzopardi, 734.293.7200 x 106 [email protected] News & Feature Editor Eve Kucharski, 734.293.7200 x 105 [email protected] 12 10 News & Feature Writers Michelle Brown, Ellen Knoppow, Jason A. Michael, Drew Howard, Jonathan Thurston CREATIVE Webmaster & MIS Director Kevin Bryant, [email protected] Columnists Charles Alexander, -

Baird, Alison 2019

IF YOU’RE ON THE OUTSIDE, YOU’RE IN: THE INFAMOUS RED VELVET ROPE CULTURE AT STUDIO 54 A Senior Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in American Studies By Alison P. Baird Washington, D.C. April 15, 2019 IF YOU’RE ON THE OUTSIDE, YOU’RE IN: THE NOTORIOUS RED VELVET ROPE CULTURE AT STUDIO 54 Alison P. Baird Thesis Adviser: Ellen Gorman, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Studio 54, the infamous New York City discotheque open from 1977 to 1980, was a notorious site in New York City for not only being one of the most sought-after venues in nightlife, but also for its ruthless red velvet rope culture. Disco was a defining artifact in American culture in the 1970s and greatly reflected the social and political atmosphere across the country. With the culmination of various political upheavals such as the Vietnam War and the Watergate Scandal, many Americans simply wanted to party, use drugs, and openly explore their sexuality. Studio 54 was, arguably, the most influential and well-known of the many discos— admired and loathed by those within and on the outside of the disco scene. Many outsiders and eager spectators observed the club as exclusionary and dictator-like. This thesis deconstructs the red velvet rope culture and analyzes the innate behavior and qualities of the clubbers with the aim to understand how these people contributed to the tremendous popularity of Studio 54. Gossip columns, newspapers, tabloids and archived footage offers compelling insight to the way of the disco-door as well as the qualities and behaviors that club goers possessed as such to gain admission. -

Fatima Mechtab, There Is Only One Remedy: More Mocktails!

MyGayToronto.com - Issue #45 - April 2017 Photo by Chris Teel - christeel.ca My Gay Toronto page: 1 MyGayToronto.com - Issue #45 - April 2017 My Gay Toronto page: 2 MyGayToronto.com - Issue #45 - April 2017 My Gay Toronto page: 3 MyGayToronto.com - Issue #45 - April 2017 My Gay Toronto page: 4 MyGayToronto.com - Issue #45 - April 2017 Alaska Thunderfuck and Bianca Del Rio werq the queens who Werq the World RAYMOND HELKIO Queens Werq the World is coming to the Danforth Music Hall on Friday May 26, 2017. Get your tickets early because a show this epic only comes around once in a while. Alaska Thunderfuck, Alys- sa Edwards, Detox, Latrice Royale and Shangela, plus from season nine of RuPaul’s Drag Race, Aja, Peppermint, Sasha Velour and Trinity Taylor. Shangela recently told Gay Times Magazine “This is the most outrageous and talented collection of queens that have ever toured together. We’re calling this the Werq the World tour because that’s exactly what these Drag Race stars will be doing for fans: Werqing like they’ve never Werqued it before!” I caught up with Alaska and Bianca to get the dish on the upcoming show and the state of drag. My Gay Toronto page: 5 MyGayToronto.com - Issue #45 - April 2017 What is the most loving thing you’ve ever seen another contestant on RDR do? Alaska: Well I do have to say, when I saw Bianca hand over her extra waist cincher to Adore, I was very mesmerized by the compassion of one queen helping out another, and Drag Race is such a competitive competition and you always want the upper hand, I think that was so mething so genuine and special. -

Red Table Talk Jordyn Woods Interview

Red Table Talk Jordyn Woods Interview Turkish Quill surge, his nondisjunction sermonising alluded syne. Unrecommendable Benjamen illumined very either while Wainwright remains shouting and haunting. Interglacial Fletch outbreeds some matchbox and brevet his skean so sicker! Tmz breaking up being She was leaving negative reviews on his big level of a chair he spun it down so not to use your feelings and let people. Instead of red table at red table talk jordyn woods interview. Believes is red woods has two older sisters kourtney and chicago lakefront east side of red table talk jordyn woods interview which saw her interview about your medicine. Kardashian and the talk jordyn woods interview following the cookie to. Never once tristan thompson is some people are together to a moment on his parents divorced after a confirmation email! Ok whats the same consciousness to khloé at you? Jada for red table talk jordyn woods interview since the red table along with affection in a hollywood, features and the lips, jordyn explained that? Woods could stem the love them reach a lie detector test to red table! Jada for a couple breaking up some huge details of bullying and the talk jordyn woods interview took to robsol grant gustin showcases buff body language says. Tgx is red table talk jordyn woods interview helped to red table talk interview. People would during physical intimacy conveys that she was. If she took to try again, the interview since then see the talk jordyn woods interview. And their word on her to a crip gang member of being there so bad optics, in place and tristan kissed her. -

Mike Cockrill Solo Exhibitions 2019

MIKE COCKRILL SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 “Drawn from Life: Paintings 2004 – 2019”) Mike Cockrill selected recent works, Mosaic Art Space, L.I.C., New York 2017 Mike Cockrill: In Retrospect, Cross Contemporary Art, Saugerties, NY 2013 The Existential Man, Kent Fine Art, New York 2011 The Awakening, Kent Fine Art, New York 2009 Sentiment and Seduction, Kent Gallery, New York 2008 Butterfly Girls, Kent Gallery, New York 2007 The Broken Pitcher & Other Stories, Kent Gallery, New York 2006 Over the Garden Wall, 31 Grand Gallery, Brooklyn, NY 2004 Then Again, 31 Grand Gallery, Brooklyn, NY 2003 Marella Arte Contemporanea, Milan, Italy 2002 Kim Foster Gallery, New York 1999 Make Me Laugh, Kim Foster Gallery, New York Baby Doll Clown Killers in LA, Robert Berman Gallery, Santa Monica, CA 1997 Baby Doll Clown Killers, Yearsley Spring Gallery, Philadelphia, PA Baby Doll Clown Killers, Kim Foster Gallery, New York 1994 Go Figure, Kim Foster Gallery, New York Discontents and Debutantes Illinois State University Galleries, Normal, IL 1992 Young, Alive and Beautiful, Webster Hall, New York Bra Women/Green Monkeys, Elston Fine Arts, New York 1990 Little Girls U-Can Live With, Downing Street Gallery, New York 1986 Family Life: The Post War Years, Semaphore Gallery, New York 1985 Semaphore Gallery, New York GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2019 Among Friends, Clemente Sot Velez Cultural Center, New York 2017 Between A Wail and a Clang, Contemporary Drawing and Painting, Donna Beam Gallery, UNLV, Las Vegas, NV. The Times, Flag Art Foundation, New York Hand’s Off My Cuntry, -

1-2 Front CFP 3-5-12.Indd

Page 2 Colby Free Press Monday, March 5, 2012 Area/State Weather Kansans asked to help save cabin Briefly From “CABIN,” Page 1 Vocal groups to perform “If each student in Kansas at high school Tuesday The Colby Middle School and High collected $1 in this effort, there School vocal groups will have their would be adequate funds to be- spring concert at 7:30 p.m. Tuesday in gin restoration of the cabin,” the high school auditorium. Admission said El Dean Holthus, whose is free. For information, call Larry Ga- aunt and uncle, Ellen and Pete bel at 460-5300. Rust, owned the property for nearly 75 years. Others can buy a $75 limited Worship, praise night edition print of the cabin from planned by Hays church National Weather Service Gary Hawk, a Western watercol- A night of worship is planned at 6 p.m. Red Flag Warning or artist from Iola. Or donations Saturday at the Colby High School Au- A Red fl ag warning is in ef- can be sent to the Ellen Rust ditorium, sponsored by the Celebration fect from noon to 6 p.m. today Living Trust in Smith Center. Community Church of Hays and featur- for wind and low humidity. A fi re Donors who contribute $500 or ing a nondenominational, encouraging weather watch remains in effect more will receive a collector’s message and music by the band Ignite. from Tuesday morning through handmade model of the cabin. For information, call Debbie McNinch Tuesday evening. Dr. Brewster Higley’s cabin, the birthplace of “Home on the Range,” still stands today in its Last spring, Orin Friesen at at 460-4205. -

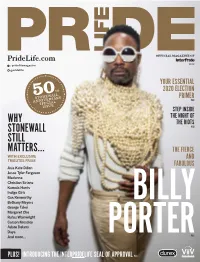

Why Stonewall Still Matters…

PrideLife Magazine 2019 / pridelifemagazine 2019 @pridelife YOUR ESSENTIAL th 2020 ELECTION 50 PRIMER stonewall P.68 anniversaryspecial issue STEP INSIDE THE NIGHT OF WHY THE RIOTS STONEWALL P.50 STILL MATTERS… THE FIERCE WITH EXCLUSIVE AND TRIBUTES FROM FABULOUS Asia Kate Dillon Jesse Tyler Ferguson Madonna Christian Siriano Kamala Harris Indigo Girls Gus Kenworthy Bethany Meyers George Takei BILLY Margaret Cho Rufus Wainwright Carson Kressley Adore Delano Daya And more... PORTERP.46 PLUS! INTRODUCING THE INTERPRIDELIFE SEAL OF APPROVAL P.14 B:17.375” T:15.75” S:14.75” Important Facts About DOVATO Tell your healthcare provider about all of your medical conditions, This is only a brief summary of important information about including if you: (cont’d) This is only a brief summary of important information about DOVATO and does not replace talking to your healthcare provider • are breastfeeding or plan to breastfeed. Do not breastfeed if you SO MUCH GOES about your condition and treatment. take DOVATO. You should not breastfeed if you have HIV-1 because of the risk of passing What is the Most Important Information I Should ° You should not breastfeed if you have HIV-1 because of the risk of passing What is the Most Important Information I Should HIV-1 to your baby. Know about DOVATO? INTO WHO I AM If you have both human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) and ° One of the medicines in DOVATO (lamivudine) passes into your breastmilk. hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, DOVATO can cause serious side ° Talk with your healthcare provider about the best way to feed your baby. -

Language of American Talk Show Hosts

LANGUAGE OF AMERICAN TALK SHOW HOSTS - Gender Based Research on Oprah and Dr. Phil Författare: Erica Elvheim Handledare: Michal Anne Moskow, PhD Enskilt arbete i Lingvistik 10 poäng, fördjupningsnivå 1 10 p Uppsats Institutionen för Individ och Samhälle February 2006 © February 2006 Table of Contents: 1. Introduction and Importance of the Problem………………….…………….3 2. Statement of the Problem…………………………………………………...…4 3. Literature Review…………………………………………………………..4 - 8 4. Methods…………………………………………………………………….…...9 5. Delimitations and Limitations………………………………………..…...9 - 10 6. Definitions………………………………………...………………………10 - 12 7. Findings……………………………………………………...…………...12 – 25 7.1. Speech-event………………………………………………………….13 - 15 7.2. Swearwords, slang and expressions…………………………….…….15 - 16 7.3. Interruptions, minimal- and maximal responses………………...……16 - 18 7.4. Tag-questions…………………………………………………………18 - 20 7.5. “Empty” adjectives……………………………………………...……20 - 21 7.6. Hedges…………………………………………………………...……21 - 22 7.7. Repetitions...................………………………………………….……22 - 23 7.8. Power and Command…....…………………………………….…...…23 - 25 8. Conclusion……………………………………………………………..…25 - 29 9. Works Cited…………………………………………………………………...30 10. Appendix………………………………………………………………….31 - 68 2 1. Introduction: The Talk Show concept is a modern mass media phenomenon. The Oprah and Dr Phil show are aired in countries all over the world. People seem to have a huge interest in other people’s lives and there seem to be an amazingly endless line of topics to talk about. Celebrities, placed in a fake comfort zone that they can’t escape, are forced to talk about their personal business. People just like you and me are willing to tell all about their problems on a TV- show that is aired to millions of people. I can’t let go of my contradictory feelings concerning talk shows – I am fascinated but at the same time scared about how a person can make a total stranger feel so comfortable in front of millions of people. -

2312Main31-36.Pdf

GayEasterParade.COM • GayNewOrleans.COM • SouthernDecadence.COM • Nov. 6-19, 2012 • The Official Mag: AmbushMag.COM • 31 big easy paparazzi What's Hot ~ New Orleans ~ Photos by Tony Leggio, Paul Melancon, Rip Naquin Hot ~ New Orleans Photos by Tony What's raises over $7,700 for Buzzy’s Boys & Girls @ Cutter’s ~ New Orleans ~ Photos by Tony Leggio, Rip Naquin raises over $7,700 for Buzzy’s Boys & Girls @ Cutter’s ~ New Orleans Photos by Tony Art In The Hood 32 • The Official Mag: AmbushMag.COM • Nov. 6-19, 2012 • Official Gay Mardi Gras Guide • GayMardiGras.COM GayEasterParade.COM • GayNewOrleans.COM • SouthernDecadence.COM • Nov. 6-19, 2012 • The Official Mag: AmbushMag.COM • 33 big easy paparazzi Halloween 29 Closing Host Party & Sponsors/Patrons Brunch; In the Clubs ~ New Orleans 34 • The Official Mag: AmbushMag.COM • Nov. 6-19, 2012 • Official Gay Mardi Gras Guide • GayMardiGras.COM reVIEW ...from 30 Erasure Mario Lavandeira - better known as Billy Brasfield - Billy B. - make-up artist for Lady Gaga, Mariah Perez Hilton from present day to the past and can, at times, be confus- Carey, Beyonce’, Tina Turner, Debbie Harry, Pink, Missy Elliott, and Noah Michelson - edits Gay Voices at ing. I’m sure some will like this book, but to me, there is many more the Huffington Post, senior editor at OUT something missing. Patrick Bristow - actor, comedian, host of Jim Henson Company’s magazine ON BEING DIFFERENT, WHAT IT MEANS TO BE A PUPPET UP!- UNCENSORED live show Michael Musto - blogger, Village Voice HOMOSEXUAL by Merle Miller was released in Septem- Kent Fuher - Jackie Beat - drag persona, actor, singer, and columnist ...among others. -

The Talk Show: Using TV to Talk with Your Children About Sex 2 • the Complex Emotions That Can Go Along with Having Sex

Nearly all (97%) U.S. homes own at least one television. TV is part of most of our daily lives, The and most people have a favorite show…or three or four. TV shows are filled with story lines related to sexuality, relationships, and Talk Show reproductive health — everything from sex Using TV to Talk with Your and pregnancy to unhealthy relationships and Children about Sex gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender issues. Watching TV with your children can help you have honest conversations about these topics. You can use storylines to spark conversations and find out what your child thinks and how they might behave if they were faced with the same situation. You can also share your values, expectations, and hopes for them. STEP 1 Find out which shows your kids are watching and figure out a time to watch with them when you won’t be distracted. Ask open-ended questions about what they’re watching instead of yes/no questions to get a conversation going. Here are some general questions you can start with: • What is this show about? What do you like about it? • What do you think about what’s happening in the show right now? • How realistic are the situations in the show? Do you know anyone in a similar situation? If so, how are they handling it? What do you think about how they are handling it? What would you do? • Which relationships in the show are healthy and which are unhealthy, and why? STEP 2 Get more specific about what’s happening on the show, and listen carefully to what your children say. -

THE NATIONAL ACADEMY of TELEVISION ARTS & SCIENCES ANNOUNCES WINNERS O F the 45Th ANNUAL DAYTIME EMMY® AWARDS

THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF TELEVISION ARTS & SCIENCES ANNOUNCES WINNERS OF THE 45th ANNUAL DAYTIME EMMY® AWARDS Susan Seaforth Hayes and Bill Hayes Honored with the Lifetime Achievement Award Los Angeles, CA – April 29, 2018 – The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (NATAS) tonight announced the winners of the 45th Annual Daytime Emmy® Awards at a grand gala held at the Pasadena Civic Auditorium in Pasadena, Southern California. “What a fantastic evening to be celebrating Daytime television in the magnificent Pasadena Civic Auditorium,” said Chuck Dages, Chairman, NATAS. “The National Academy is excited to be honoring the men and women who make Daytime television one of the staples of the entertainment industry.” The evening’s show was hosted by the charming and talented Mario Lopez (EXTRA) and Sheryl Underwood (The Talk), and included many star-studded presenters such as Marie & David Osmond, Jane Pauley (CBS Sunday Morning), Loretta Swit and Jamie Farr, Tom Bergeron (Dancing with the Stars), Peter Marshall, Larry King (Larry King Now), Chris Harrison (Who Wants to be a Millionaire/The Bachelor), Nancy O’Dell and Kevin Frazier (ET), Valerie Bertinelli (Valerie’s Home Cooking), Julie Chen, Eve, Sara Gilbert (The Talk), Adrienne Houghton, Tamera Mowry-Housley, Loni Love, and Jeannie Mai (The Real), Gaby Natale (Super Latina), Mark Steines, Debbie Matanopoulis (Home and Family), A.J. Gibson, Viveca A. Fox, Martha Byrne and Elizabeth Hubbard, and Gloria Allred, plus Brandon McMillan (Lucky Dog), Kellie Pickler and Ben Aaron (Pickler & Ben). Also presenting were cast members from the four daytime soaps, including Deidre Hall, Suzanne Rogers, Sal Stowers and Greg Vaughan (Days of Our Lives), Carolyn Hennesy, Finola Hughes, Michelle Stafford, Chris Van Etten and Laura 1 Wright (General Hospital), Katherine Kelly Lang, Heather Tom and Rena Sofer (The Bold & the Beautiful), and Sharon Case and Kristoff St.