A. Marshall of the United States Army

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memorial Day 2021

MEMORIAL DAY 2021 Virgil Poe and RC Pelton This article is dedicated to the families and friends of all soldiers, sailors and Marines who did not survive war and those who did survive but suffered with battle fatigue Shell Shock, or PTSD . Virgil Poe served in the US ARMY DURING WORLD WAR ll. HE WAS IN THE BATTLE OF THE BULGE AS WAS MY UNCLE LOWELL PELTON. As a teenager, Virgil Poe, a 95 year old WWII veteran served in 3rd army and 4th army in field artillery units in Europe (France, Belgium Luxemburg, and Germany) He recently was awarded the French Legion of Honor for his WWII service. Authorized by the President of France, it is the highest Military Medal in France. After the war in Germany concluded, he was sent to Fort Hood Texas to be reequipped for the invasion of Japan. But Japan surrendered before he was shipped to the Pacific. He still calls Houston home. Ernest Lowell Pelton My Uncle Ernest Lowell Pelton was there with Virgil during the battle serving as a Medic in Tank Battalion led by General Gorge Patton. During the battle he was wounded while tending to 2 fellow soldiers. When found they were both dead and Lowell was thought dead but still barely alive. He ended up in a hospital in France where he recovered over an 8-month period. He then asked to go back to war which he did. Lowell was offered a battlefield commission, but declined saying, I do not want to lead men into death. In Anson Texas he was called Major since all the small-town residents had heard of his heroism. -

The United States Atomic Army, 1956-1960 Dissertation

INTIMIDATING THE WORLD: THE UNITED STATES ATOMIC ARMY, 1956-1960 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Paul C. Jussel, B.A., M.M.A.S., M.S.S. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2004 Dissertation Committee Approved by Professor Allan R. Millett, Advisor Professor John R. Guilmartin __________________ Professor William R. Childs Advisor Department of History ABSTRACT The atomic bomb created a new military dynamic for the world in 1945. The bomb, if used properly, could replace the artillery fires and air-delivered bombs used to defeat the concentrated force of an enemy. The weapon provided the U.S. with an unparalleled advantage over the rest of the world, until the Soviet Union developed its own bomb by 1949 and symmetry in warfare returned. Soon, theories of warfare changed to reflect the belief that the best way to avoid the effects of the bomb was through dispersion of forces. Eventually, the American Army reorganized its divisions from the traditional three-unit organization to a new five-unit organization, dubbed pentomic by its Chief of Staff, General Maxwell D. Taylor. While atomic weapons certainly had an effect on Taylor’s reasoning to adopt the pentomic organization, the idea was not new in 1956; the Army hierarchy had been wrestling with restructuring since the end of World War II. Though the Korean War derailed the Army’s plans for the early fifties, it returned to the forefront under the Eisenhower Administration. The driving force behind reorganization in 1952 was not ii only the reoriented and reduced defense budget, but also the Army’s inroads to the atomic club, formerly the domain of only the Air Force and the Navy. -

EXTENSIONS of REMARKS, Vol

32618 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS, Vol. 155, Pt. 24 December 17, 2009 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS HONORING ROSE KAUFMAN rollcall Vote No. 933; H. Res. 940, rollcall Vote is that of the largest land battle in our Army’s No. 934; H. Res. 845, rollcall Vote No. 935; history and the turning point of World War II. HON. NANCY PELOSI H.R. 2278, rollcall Vote No. 936; H. Res. 915, Its precedent is the model it provides, even OF CALIFORNIA rollcall Vote No. 937; and H. Res. 907, rollcall today, for our men and women in combat. IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Vote No. 938. During my 31 years of service in the Navy, I f witnessed acts of extraordinary bravery and Wednesday, December 16, 2009 resolve among the men and women under my HONORING THE 65TH ANNIVER- Ms. PELOSI. Madam Speaker, I rise today command. As a Vice Admiral, I was honored SARY OF THE BATTLE OF THE to honor the life of an extraordinary wife, to serve with the finest sailors that our country BULGE mother, grandmother, and artist, Rose Kauf- has to offer and witness these men and man. women perform their duties with the same pur- The Pelosi family was blessed to be forever HON. JOE SESTAK pose and spirit that led the Allied Forces to joined to the Kaufman family when our daugh- OF PENNSYLVANIA victory 65 years ago. ter Christine married Rose and Phil’s son, IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES This past August, I was honored with the Peter. Their wedding brought us all closer to- Wednesday, December 16, 2009 opportunity to welcome the 83rd Infantry Divi- gether and made us a single family and dear Mr. -

ORAL HISTORY Lieutenant General John H. Cushman US Army, Retired

ORAL HISTORY Lieutenant General John H. Cushman US Army, Retired VOLUME FOUR TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Title Pages Preface 1 18 Cdr Fort Devens, MA 18-1 to 18-18 19 Advisor, IV Corps/Military Region 4, Vietnam 19-1 to 19A-5 20 Cdr 101st Airborne Division & Fort Campbell, KY 20-1 to 20-29 Preface I began this Oral History with an interview in January 2009 at the US Army Military History Institute at Carlisle Barracks, PA. Subsequent interviews have taken place at the Knollwood Military Retirement Residence in Washington, DC. The interviewer has been historian Robert Mages. Until March 2011 Mr. Mages was as- signed to the Military History Institute. He has continued the project while assigned to the Center of Military History, Fort McNair, DC. Chapter Title Pages 1 Born in China 1-1 to 1-13 2 Growing Up 2-1 to 2-15 3 Soldier 3-1 to 3-7 4 West Point Cadet 4-1 to 4-14 5 Commissioned 5-1 to 5-15 6 Sandia Base 6-1 to 6-16 7 MIT and Fort Belvoir 7-1 to 7-10 8 Infantryman 8-1 to 8-27 9 CGSC, Fort Leavenworth, KS, 1954-1958 9-1 to 9-22 10 Coordination Group, Office of the Army Chief of Staff 10-1 to 10-8 11 With Cyrus Vance, Defense General Counsel 11-1 to 11-9 12 With Cyrus Vance, Secretary of the Army 12-1 to 12-9 13 With the Army Concept Team in Vietnam 13-1 to 13-15 14 With the ARVN 21st Division, Vietnam 14-1 to 14-19 15 At the National War College 15-1 to 15-11 16 At the 101st Airborne Division, Fort Campbell, KY 16-1 to 16-10 17 Cdr 2d Brigade, 101st Airborne Division, Vietnam 17-1 to 17-35 18 Cdr Fort Devens, MA 18-1 to 18-18 19 Advisor, IV Corps/Military Region 4, Vietnam 19-1 to 19A-5 20 Cdr 101st Airborne Division & Fort Campbell, KY 19-1 to 19-29 21 Cdr Combined Arms Center and Commandant CGSC 22 Cdr I Corps (ROK/US) Group, Korea 23 In Retirement (interviews for the above three chapters have not been conducted) For my own distribution in November 2012 I had Chapters 1 through 7 (Volume One) print- ed. -

Soldiers and Statesmen

, SOLDIERS AND STATESMEN For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price $2.65 Stock Number008-070-00335-0 Catalog Number D 301.78:970 The Military History Symposium is sponsored jointly by the Department of History and the Association of Graduates, United States Air Force Academy 1970 Military History Symposium Steering Committee: Colonel Alfred F. Hurley, Chairman Lt. Colonel Elliott L. Johnson Major David MacIsaac, Executive Director Captain Donald W. Nelson, Deputy Director Captain Frederick L. Metcalf SOLDIERS AND STATESMEN The Proceedings of the 4th Military History Symposium United States Air Force Academy 22-23 October 1970 Edited by Monte D. Wright, Lt. Colonel, USAF, Air Force Academy and Lawrence J. Paszek, Office of Air Force History Office of Air Force History, Headquarters USAF and United States Air Force Academy Washington: 1973 The Military History Symposia of the USAF Academy 1. May 1967. Current Concepts in Military History. Proceedings not published. 2. May 1968. Command and Commanders in Modem Warfare. Proceedings published: Colorado Springs: USAF Academy, 1269; 2d ed., enlarged, Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1972. 3. May 1969. Science, Technology, and Warfare. Proceedings published: Washington, b.C.: Government Printing Office, 197 1. 4. October 1970. Soldiers and Statesmen. Present volume. 5. October 1972. The Military and Society. Proceedings to be published. Views or opinions expressed or implied in this publication are those of the authors and are not to be construed as carrying official sanction of the Department of the Air Force or of the United States Air Force Academy. -

Operation-Overlord.Pdf

A Guide To Historical Holdings In the Eisenhower Library Operation OVERLORD Compiled by Valoise Armstrong Page 4 INTRODUCTION This guide contains a listing of collections in the Dwight D. Eisenhower Library relating to the planning and execution of Operation Overlord, including documents relating to the D-Day Invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944. That monumental event has been commemorated frequently since the end of the war and material related to those anniversary observances is also represented in these collections and listed in this guide. The overview of the manuscript collections describes the relationship between the creators and Operation Overlord and lists the types of relevant documents found within those collections. This is followed by a detailed folder list of the manuscript collections, list of relevant oral history transcripts, a list of related audiovisual materials, and a selected bibliography of printed materials. DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER LIBRARY Abilene, Kansas 67410 September 2006 Table of Contents Section Page Overview of Collections…………………………………………….5 Detailed Folder Lists……………………………………………….12 Oral History Transcripts……………………………………………41 Audiovisual: Still Photographs…………………………………….42 Audiovisual: Audio Recordings……………………………………43 Audiovisual: Motion Picture Film………………………………….44 Select Bibliography of Print Materials…………………………….49 Page 5 OO Page 6 Overview of Collections BARKER, RAY W.: Papers, 1943-1945 In 1942 General George Marshall ordered General Ray Barker to London to work with the British planners on the cross-channel invasion. His papers include minutes of meetings, reports and other related documents. BULKELEY, JOHN D.: Papers, 1928-1984 John Bulkeley, a career naval officer, graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1933 and was serving in the Pacific at the start of World War II. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 111 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 111 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 155 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, DECEMBER 17, 2009 No. 192 House of Representatives The House was not in session today. Its next meeting will be held on Saturday, December 19, 2009, at 6 p.m. Senate The Senate met at 10 a.m. and was O God, from whom all noble desires ings, enabling them to see and experi- called to order by the Honorable and all good counsels do proceed, crown ence evidences of Your love. May their KIRSTEN E. GILLIBRAND, a Senator from the deliberations of our lawmakers consistent communication with You the State of New York. with spacious thinking and with sym- radiate in their faces, be expressed in pathy for all humanity. As they face their character, and be exuded in posi- PRAYER perplexing questions, quicken in them tive joy. Sanctify this day of labor The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- every noble impulse, transforming fered the following prayer: their work into a throne of service. with the benediction of Your approval. Let us pray. Lord, shower them with Your bless- We pray in Your great Name. Amen. NOTICE If the 111th Congress, 1st Session, adjourns sine die on or before December 23, 2009, a final issue of the Congres- sional Record for the 111th Congress, 1st Session, will be published on Thursday, December 31, 2009, to permit Members to insert statements. All material for insertion must be signed by the Member and delivered to the respective offices of the Official Reporters of Debates (Room HT–59 or S–123 of the Capitol), Monday through Friday, between the hours of 10:00 a.m. -

Chief's File Cabinet

CHIEF’S FILE CABINET Ronny J. Coleman ____________________________________ Lazy Boy Learning Colonel David Hackworth was one of the most decorated soldiers of the Vietnam War. He earned over ninety service decorations, which consisted of both personal and organizational citations. After he retired he wrote a book, with author Julie Sherman entitled “About Face: the Odyssey of an American Warrior”. 1In that book he touts the theory that every fire officer in this country needs to literally understand. His admonition to all of those who are going to take people into combat was “practice doesn’t make perfect – it makes it permanent…..” And “Sweat in training saves blood on the battlefield." In other words, what the Colonel was telling us then was that repetition over and over again does not make us perfect especially if the repetition is done improperly or inappropriately. Repeating mistakes of the past is simply not an effective strategy of being able to predict future performance. No where can this be any truer than in the concept of training of our firefighters for their role in combat. If you are like me you are probably getting very frustrated with reading continuous stories about firefighters being killed or worse yet badly injured at the scenes of fires. And probably the worst of all is when you read a story about a firefighter dying in a training exercise. In almost all cases practice did not make it perfect for these individuals. What is being made permanent, is their death and/or long term recovery from something that could or should have never happened in the first place. -

Annual Report 2020

2020 Annual Report Division of Military and Naval Affairs 2020 ANNUAL REPORT 1 Division of Military and Naval Affairs 2020 Annual Report The Adjutant General DMNA was Ready and Responsive for New Yorkers in Historic 2020 Mission During 2020 the men and women of the performed exceptionally. New York Army and Air National Guard, As 2020 came to a close, the New York New York Naval Militia, the New York National Guard was also one of two Guard and the civilian workforce of the National Guard contingents to play a role Division of Military and Naval Affairs per- in testing the logistics of receiving and formed magnificently as New York State distributing the Pfizer Coronavirus vaccine grappled with the worldwide coronavirus to military personnel in December. Just pandemic. under 1,000 of our personnel were vac- As New York mobilized to cope with the cinated without a hitch. pandemic, National Guard Soldiers and Meanwhile, we continued to maintain Airmen stepped forward to help their fel- Joint Task Force Empire Shield, our low citizens from Long Island to Buffalo. security augmentation force in New York This Division of Military and Naval Affairs City, and provided a small contingent of Annual Report reflects the efforts of our troops to help local governments deal with Maj. Gen. Ray F. Shields men and women here at home, while flooding along Lake Ontario’s shoreline in Guard Soldiers and Airmen also served the spring. U.S. and allied forces with the MQ-9 re- the nation overseas. motely piloted vehicle. A handful of Airmen At the same time, over 650 Soldiers of even assisted California in fighting wild- Over 5,000 service members took part in the 42nd Infantry Division’s headquarters fires, supporting the California National the COVID-19 pandemic response mis- served in countries across the Middle Guard during the spring and summer. -

Our Wisconsin Boys in Épinal Military Cemetery, France

Our Wisconsin Boys in Épinal Military Cemetery, France by the students of History 357: The Second World War 1 The Students of History 357: The Second World War University of Wisconsin, Madison Victor Alicea, Victoria Atkinson, Matthew Becka, Amelia Boehme, Ally Boutelle, Elizabeth Braunreuther, Michael Brennan, Ben Caulfield, Kristen Collins, Rachel Conger, Mitch Dannenberg, Megan Dewane, Tony Dewane, Trent Dietsche, Lindsay Dupre, Kelly Fisher, Amanda Hanson, Megan Hatten, Sarah Hogue, Sarah Jensen, Casey Kalman, Ted Knudson, Chris Kozak, Nicole Lederich, Anna Leuman, Katie Lorge, Abigail Miller, Alexandra Niemann, Corinne Nierzwicki, Matt Persike, Alex Pfeil, Andrew Rahn, Emily Rappleye, Cat Roehre, Melanie Ross, Zachary Schwarz, Savannah Simpson, Charles Schellpeper, John Schermetzler, Hannah Strey, Alex Tucker, Charlie Ward, Shuang Wu, Jennifer Zelenko 2 The students of History 357 with Professor Roberts 3 Foreword This project began with an email from Monsieur Joel Houot, a French citizen from the village of Val d’Ajol to Mary Louise Roberts, professor of History at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. Mr. Houot wrote to Professor Roberts, an historian of the American G.I.s in Normandy, to request information about Robert Kellett, an American G.I. buried in Épinal military cemetary, located near his home. The email, reproduced here in French and English, was as follows: Bonjour madame...Je demeure dans le village du Val d'Ajol dans les Vosges, et non loin de la se trouve le cimetière américain du Quéquement à Dinozé-Épinal ou repose 5255 sodats américains tombés pour notre liberté. J'appartiens à une association qui consiste a parrainer une ou plusieurs tombes de soldat...a nous de les honorer et à fleurir leur dernière demeure...Nous avons les noms et le matricule de ces héros et également leur état d'origine...moi même je parraine le lieutenant KELLETT, Robert matricule 01061440 qui a servi au 315 th infantry régiment de la 79 th infantry division, il a été tué le 20 novembre 1944 sur le sol de France... -

Video File Finding

Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum (714) 983 9120 ◦ http://www.nixonlibrary.gov ◦ [email protected] MAIN VIDEO FILE ● MVF-001 NBC NEWS SPECIAL REPORT: David Frost Interviews Henry Kissinger (10/11/1979) "Henry Kissinger talks about war and peace and about his decisions at the height of his powers" during four years in the White House Runtime: 01:00:00 Participants: Henry Kissinger and Sir David Frost Network/Producer: NBC News. Original Format: 3/4-inch U-Matic videotape Videotape. Cross Reference: DVD reference copy available. DVD reference copy available ● MVF-002 "CNN Take Two: Interview with John Ehrlichman" (1982, Chicago, IL and Atlanta, GA) In discussing his book "Witness to Power: The Nixon Years", Ehrlichman comments on the following topics: efforts by the President's staff to manipulate news, stopping information leaks, interaction between the President and his staff, FBI surveillance, and payments to Watergate burglars Runtime: 10:00 Participants: Chris Curle, Don Farmer, John Ehrlichman Keywords: Watergate Network/Producer: CNN. Original Format: 3/4-inch U-Matic videotape Videotape. DVD reference copy available ● MVF-003 "Our World: Secrets and Surprises - The Fall of (19)'48" (1/1/1987) Ellerbee and Gandolf narrate an historical overview of United States society and popular culture in 1948. Topics include movies, new cars, retail sales, clothes, sexual mores, the advent of television, the 33 1/3 long playing phonograph record, radio shows, the Berlin Airlift, and the Truman vs. Dewey presidential election Runtime: 1:00:00 Participants: Hosts Linda Ellerbee and Ray Gandolf, Stuart Symington, Clark Clifford, Burns Roper Keywords: sex, sexuality, cars, automobiles, tranportation, clothes, fashion Network/Producer: ABC News. -

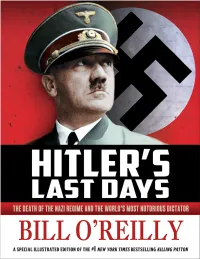

Hitlers-Last-Days-By-Bill-Oreilly-Excerpt

207-60729_ch00_6P.indd ii 7/7/15 8:42 AM Henry Holt and Com pany, LLC Publishers since 1866 175 Fifth Ave nue, New York, New York 10010 macteenbooks . com Henry Holt® is a registered trademark of Henry Holt and Com pany, LLC. Copyright © 2015 by Bill O’Reilly All rights reserved. Permission to use the following images is gratefully acknowledged (additional credits are noted with captions): Mary Evans Picture Library— endpapers, pp. ii, v, vi, 35, 135, 248, 251; Bridgeman Art Library— endpapers, p. iii; Heinrich Hoffman/Getty— p. 1. All maps by Gene Thorp. Case design by Meredith Pratt. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data O’Reilly, Bill. Hitler’s last days : the death of the Nazi regime and the world’s most notorious dictator / Bill O’Reilly. — First edition. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-62779-396-4 (hardcover) • ISBN 978-1-62779-397-1 (e- book) 1. Hitler, Adolf, 1889–1945. 2. Hitler, Adolf, 1889–1945— Death and burial. 3. World War, 1939–1945— Campaigns— Germany. 4. Berlin, Battle of, Berlin, Germany, 1945. 5. Heads of state— Germany— Biography. 6. Dictators— Germany— Biography. I. O’Reilly, Bill. Killing Patton. II. Title. DD247.H5O735 2015 943.086092— dc23 2015000562 Henry Holt books may be purchased for business or promotional use. For information on bulk purchases, please contact the Macmillan Corporate and Premium Sales Department at (800) 221-7945 x5442 or by e-mail at specialmarkets@macmillan . com. First edition—2015 / Designed by Meredith Pratt Based on the book Killing Patton by Bill O’Reilly, published by Henry Holt and Com pany, LLC.