Thesis Will Take on the Scholarly Challenges Presented by Ta- Bari’S Chronicle by Using a Specific Method: Narratology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University Microfilms International 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48'L06 USA St

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You willa find good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the mBteriaj being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at thu upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

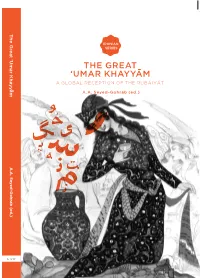

The Great 'Umar Khayyam

The Great ‘Umar Khayyam Great The IRANIAN IRANIAN SERIES SERIES The Rubáiyát by the Persian poet ‘Umar Khayyam (1048-1131) have been used in contemporary Iran as resistance literature, symbolizing the THE GREAT secularist voice in cultural debates. While Islamic fundamentalists criticize ‘UMAR KHAYYAM Khayyam as an atheist and materialist philosopher who questions God’s creation and the promise of reward or punishment in the hereafter, some A GLOBAL RECEPTION OF THE RUBÁIYÁT secularist intellectuals regard him as an example of a scientist who scrutinizes the mysteries of the universe. Others see him as a spiritual A.A. Seyed-Gohrab (ed.) master, a Sufi, who guides people to the truth. This remarkable volume collects eighteen essays on the history of the reception of ‘Umar Khayyam in various literary traditions, exploring how his philosophy of doubt, carpe diem, hedonism, and in vino veritas has inspired generations of poets, novelists, painters, musicians, calligraphers and filmmakers. ‘This is a volume which anybody interested in the field of Persian Studies, or in a study of ‘Umar Khayyam and also Edward Fitzgerald, will welcome with much satisfaction!’ Christine Van Ruymbeke, University of Cambridge Ali-Asghar Seyed-Gohrab is Associate Professor of Persian Literature and Culture at Leiden University. A.A. Seyed-Gohrab (ed.) A.A. Seyed-Gohrab WWW.LUP.NL 9 789087 281571 LEIDEN UNIVERSITY PRESS The Great <Umar Khayyæm Iranian Studies Series The Iranian Studies Series publishes high-quality scholarship on various aspects of Iranian civilisation, covering both contemporary and classical cultures of the Persian cultural area. The contemporary Persian-speaking area includes Iran, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Central Asia, while classi- cal societies using Persian as a literary and cultural language were located in Anatolia, Caucasus, Central Asia and the Indo-Pakistani subcontinent. -

A Literary History of Persia

r-He weLL read mason li""-I:~I=-•I cl••'ILei,=:-,•• Dear Reader, This book was referenced in one of the 185 issues of 'The Builder' Magazine which was published between January 1915 and May 1930. To celebrate the centennial of this publication, the Pictoumasons website presents a complete set of indexed issues of the magazine. As far as the editor was able to, books which were suggested to the reader have been searched for on the internet and included in 'The Builder' library.' This is a book that was preserved for generations on library shelves before it was carefully scanned by one of several organizations as part of a project to make the world's books discoverable online. Wherever possible, the source and original scanner identification has been retained. Only blank pages have been removed and this header- page added. The original book has survived long enough for the copyright to expire and the book to enter the public domain. A public domain book is one that was never subject to copyright or whose legal copyright term has expired. Whether a book is in the public domain may vary country to country. Public domain books belong to the public and 'pictoumasons' makes no claim of ownership to any of the books in this library; we are merely their custodians. Often, marks, notations and other marginalia present in the original volume will appear in these files – a reminder of this book's long journey from the publisher to a library and finally to you. Since you are reading this book now, you can probably also keep a copy of it on your computer, so we ask you to Keep it legal. -

Exile from Exile: the Representation of Cultural Memory in Literary Texts by Exiled Iranian Jewish Women

Langer, Jennifer (2013) Exile from exile: the representation of cultural memory in literary texts by exiled Iranian Jewish women. PhD Thesis. SOAS, University of London http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/17841 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. EXILE FROM EXILE: THE REPRESENTATION OF CULTURAL MEMORY IN LITERARY TEXTS BY EXILED IRANIAN JEWISH WOMEN JENNIFER LANGER Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD 2013 Shahin’s Ardashir-nameh, Iran, 17th century; Library of the Jewish Theological Seminary Centre for Gender Studies School of Oriental and African Studies University of London Declaration for PhD thesis I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for students of the School of Oriental and African Studies concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. I also undertake that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged in the work which I present for examination. -

The Prophet and the Age Ofthe Caliphates

Kennedy_ppr 30/06/2006 06:29 AM Page 1 THE CALIPHATES THE PROPHET AND AGE OF The Near East and Islamic society have never been as close to the forefront of international attention. In this time of conflict the Western population is increasingly eager to expand their knowledge of the region’s past. This updated edition of Hugh Kennedy’s popular introduction to the history of the Near East is a timely aid to this quest for knowledge about the roots of Islam. The Prophet and the Age of Caliphates is an accessible guide to the history of the Near East from c.600–1050AD, the period in which Islamic society was formed. Beginning with the life of Muhammad and the birth of Islam, Kennedy goes on to explore the great Arab conquests of the seventh century and the golden age of the Umayyad and Abbasid caliphates when the world of Islam was politically and culturally far more developed than the West. A period of political fragmentation shattered this early unity, never to be recovered. This new edition takes into account new research on early Islam and contains a fully updated bibliography. Based on extensive reading of the original Arabic sources, Kennedy breaks away from the Orientalist tradition of seeing early Islamic history as a series of ephemeral rulers and pointless battles by drawing attention to underlying long term social and economic processes. This book deals with issues of continuing and increasing relevance in the twenty-first century, when it is, perhaps, more important than ever to understand the early development of the Islamic world. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Sayyed Ahmad Kasravi historian, language reformer and thinker Ramyar, Minoo How to cite: Ramyar, Minoo (1969) Sayyed Ahmad Kasravi historian, language reformer and thinker, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/10016/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk ABSTRACT Sayyed Ahmad Kasravi Historian, Language Reformer and Thinker. Sayyed Ahmad Kasravi was one of the greatest scholars and thinkers of 20th-century Iran, He had alreadywon an international reputation as a historian and as a linguist before he was murdered by a religious fanatic in 19^5* His ideas about language reform, literature, religion and politics challenged traditional Iranian ways of thinking. The purpose of this thesis is to outline the contents of Kasravi's writings, to quote comments by his admirers and critics, and to express our own views when possible. -

“AZERBAIJAN” by Alireza Hodaei S

THE VOICE OF A PERIPHERY LOST IN THE COLD WAR; FIRQE-YI DEMOKRAT AND ITS OFFICIAL NEWSPAPER “AZERBAIJAN” By Alireza Hodaei Submitted to Central European University Department of History In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Art Supervisor: Professor Charles Shaw Second Reader: Professor Tolga Esmer CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2017 Copyright Notice Copyright in the text of this thesis rests with the Author. Copies by any process, either in full or part, may be made only in accordance with the instructions given by the Author and lodged in the Central European University Library. Details may be obtained from the librarian. This page must form a part of any such copies made. Further copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the written permission of the Author. CEU eTD Collection i Abstract The rise and fall of the Firqey-i Demokrat (The Democrat Party) and the establishment of the Azerbaijan People’s Government in the winter of 1945 has been a matter of scholarly interest for decades. The Azerbaijan People’s Government (APG) was a self-declared autonomous Government in northwest Iran, Iranian Azerbaijan, headed by Seyyed Jafar Pishavari in December of 1945, which lasted only for a year. The life of the short-lived government and of its leader, Pishavari, is contested among scholars with different ideological orientations. While many see the APG as nothing but a Soviet designed plan, others describe it as a mass mobilization against the injustices of the central government in Tehran. The result of the near half-century battle was the production of reductionist histories in Farsi, Azerbaijani Turkish, and English, the primary concern of which was to prove or disprove Soviet support for the APG and thus discredit or legitimize it. -

![Downloaded by [New York University] at 12:17 05 August 2016 the Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates Third Edition](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9052/downloaded-by-new-york-university-at-12-17-05-august-2016-the-prophet-and-the-age-of-the-caliphates-third-edition-10189052.webp)

Downloaded by [New York University] at 12:17 05 August 2016 the Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates Third Edition

Downloaded by [New York University] at 12:17 05 August 2016 The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates Third Edition The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates is an accessible history of the Near East from c. AD 600 to 1050, the period in which Islamic society was formed. Begin- ning with the life of Muhammad and the birth of Islam, Hugh Kennedy goes on to explore the great Arab conquests of the seventh century and the golden age of the Umayyad and Abbasid caliphates when the world of Islam was politi- cally and culturally far more developed than the West. The arrival of the Seljuk Turks and the period of political fragmentation which followed shattered this early unity, never to be recovered. This new edition is fully updated to take into account the considerable amount of new research on early Islam, and contains a completely revised bib- liography. Based on extensive reading of the original Arabic sources, Kennedy breaks away from the Orientalist tradition of seeing early Islamic history as a series of ephemeral rulers and pointless battles by drawing attention to underly- ing long-term social and economic processes. The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates deals with issues of continuing and increasing relevance in the twenty-first century, when it is, perhaps, more important than ever to understand the early development of the Islamic world. Students and scholars of early Islamic history will find this book a clear, inform- ative and readable introduction to the subject. Hugh Kennedy is Professor of Arabic at SOAS, University of London. -

Background Guide Will Instead Focus on Several Key Empires That Proved Most Important to Shaping Iran at the Time of Committee

Cabinet of Iran (1951) MUNUC 33 ONLINE1 Cabinet of Iran (1951) | MUNUC 33 Online TABLE OF CONTENTS ______________________________________________________ CHAIR LETTER…………………………….….………………………….………. 3 HISTORY OF IRAN……………..………………………………………………...6 CURRENT SITUATION…………………………………………………………..26 BLOC POSITIONS………………………………………………………………32 BIBLIOGRAPHY………………………………………………………………...37 2 Cabinet of Iran (1951) | MUNUC 33 Online CHAIR LETTER ____________________________________________________ Dear Delegates, Welcome to Iran, 1951! My name is Isaac Kamber, and I will be the chair of this committee. I’m incredibly excited to run an exciting, fun-filled committee for all of you come February. A little bit about myself: I’m currently a fourth year at the University of Chicago majoring in Near Eastern Languages & Civilizations and Geographical Sciences (because one obscure major wasn’t enough…). I am the Chief Operating Officer of MUNUC XXIII. Last year, I served as Under-Secretary- General for Continuous Crisis Committees and was the Chair of the Cabinet of Uzbekistan, 1991 the year prior to that. I also staff UChicago’s collegiate Model UN conference, ChoMUN, and travel on our competitive team. Outside of the MUNiverse, I do research on air quality and public health in Chicago with the Center for Spatial Data Science. I grew up in New Jersey, but my family moved out to Colorado a couple years ago, so when I want to sound original, I tell people I’m from Colorado. This committee offers you the chance to engage firsthand with one of the most interesting and consequential periods in modern Middle Eastern history. Iran during the early 1950s was in a state of flux. Long subjugated by foreign powers like the UK, US, and USSR, Iran finally began to assert its sovereignty. -

Introduction Chapter 1

Notes Introduction 1. BBC News Africa, “Tunisian Martyr,” http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/ world-africa-12241082. 2. Filiu, Arab Revolution, 20. 3. Lapidus, History of Islamic Societies, 606. 4. Filiu, Arab Revolution, 15. 5. Ibid., 21. 6. Ismael and Ismael, Continuity & Change, 372– 73. 7. Filiu, Arab Revolution, 7. 8. Leverett, Inheriting Syria, 167. 9. Filiu, Arab Revolution, 8. 10. Lapidus, History of Islamic Societies, 576– 80. 11. Jones, Qur’an, 114. I wish to thank Professor Alan Jones for drawing my attention to this reference and to the ones listed below. 12. Ibid., 270. 13. Ibid., 329. 14. Ibid., 411. 15. Ibid., 95. 16. Afsaruddin, First Muslims, 26. 17. Madelung, Succession, 18. 18. Ibid., 253. For Ghadir Khumm, see Afsaruddin, Excellence & Prece- dence, 158, 160, 161, 173, 200, 212, 214, 215, 219, 226, 228, and 267. 19. Madelung, Succession, 18– 27. 20. Afsaruddin, First Muslims, 19. Chapter 1 1. Hitti, History of the Arabs, 178. 2. Al- Ya‘qubi, Ta’rikh II, 7– 11; al- Tabari, Ta’rikh I, 1832 and 1837. 3. Al- Ya‘qubi, Ta’rikh II, 7; al- Tabari, Ta’rikh I, 1839. 4. Al-Ya‘qubi, Ta’rikh II, 7; al- Tabari, Ta’rikh I, 1823 and 1842. 5. Al-Tabari, Ta’rikh I, 1842– 43. 166 Notes 6. Al- Ya‘qubi, Ta’rikh II, 9; al- Tabari, Ta’rikh I, 1843– 45; Kennedy, Prophet, 53. 7. Kennedy, Prophet, 54– 57. 8. Ibn Khayyat, Ta’rikh I, 92– 105, 107– 116, 120– 25; al- Ya‘qubi, Ta’rikh II, 28– 34, 38– 42, 46– 49. -

Baltacioglu-Brammer Dissertation

Safavid Conversion Propaganda in Ottoman Anatolia and the Ottoman Reaction, 1440s-1630s Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University by Ayse Baltacioglu-Brammer, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2016 Dissertation Committee: Jane Hathaway, Advisor Carter V. Findley Scott Levi Copyright by Ayse Baltacioglu-Brammer 2016 Abstract This dissertation explores the Sunni-Shi‘ite divergence in the early modern period, not merely as religiously derived, but as a meticulously carried out geo-political battle that formed the base of the sectarian conflict in the region today. One of the few studies to utilize both Safavid and Ottoman primary sources within the framework of identity formation and propaganda, my study argues that the “religious dichotomy” between “Ottoman Sunnism” and “Safavid Shi‘ism” was a product of the Safavid- Ottoman geo-political and fiscal rivalry rather than its cause; it further holds that examining the Shiitization of Safavid Iran and Ottoman Anatolia within a larger geo- political framework is critical to understanding early modern Middle Eastern states and societies. At the time, the Shi‘ite population of Anatolia – called Kızılbaş (“red heads” in Turkish) – constituted the largest Muslim minority group in the Ottoman Empire and was the principal catalyst for conflict between the Ottoman and Safavid empires. Yet it was only after the politicization of the Safaviyya Sufi movement that Istanbul perceived its Kızılbaş subjects as a threat to its geo-political legitimacy and security in the volatile regions of central and eastern Anatolia, as well as the frontier regions of Iraq. -

The Grand Strategy of the Russian Empire in the Caucasus Against Its Southern Rivals (1821-1833)

The London School of Economics and Political Science The Grand Strategy of the Russian Empire in the Caucasus against Its Southern Rivals (1821-1833) Serkan Keçeci A dissertation submitted to the Department of International History of the London School of Economics and Political Science for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, October 2016. 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 99,995 words. 2 Abstract This dissertation will analyse the grand strategy of the Russian empire against its southern rivals, namely the Ottoman empire and Iran, in the Caucasus, between 1821 and 1833. This research is interested in explaining how the Russian imperial machine devised and executed successful strategies to use its relative superiority over the Ottomans and the Qājārs and secure domination of the region. Russian success needs, however, to be understood within a broader context that also takes in Ottoman and Iranian policy-making and perspectives, and is informed by a comparative sense of the strengths and weaknesses of all three imperial regimes.