University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reinhardt's Choice: Some Alternatives to Weill?

DAVID DREW Reinhardt's Choice: Some Alternatives to Weill? The pretexts for the present paper are the author's essays >Der T#g der Ver heissung and the Prophecies of jeremiah<, Tempo, 206 (October 1998), 11- 20, and >Der T#g der Verheissung: Weill at the Crossroads<, 1impo, 208 (April 1999), 335-50. As suggested in the preface to the second essay, the paper is intended to function both as a free-standing entity and as an extended bridge between the last section of the earlier essay and the first section of its successor. According to Meyer Weisgal's detailed account of the origins of The Eter nal Road, Reinhardt had no inkling of his plans until their November 1933 meeting in Paris.1 Weisgal began by outlining the idea of a biblical drama that would for the first time evoke the Old Testan1ent in all its breadth rather than in isolated episodes. At the end of his account, according to Weisgal, Reinhardt sat motionless and in silence before saying »very sim ply<< »But who will be the author of this biblical play and who will write the mu sic?<< . »You are the master<< , I said, ••It is up to you to select them<<. Again there was a long uncomfortable pause and Reinhardt said that he would ask Franz Werfel and Kurt Weill to collaborate with him. With or without prior notice2, the problems inherent in Weisgal's com mission were so complex that Reinhardt would have had good reason for Meyer W. Weisgal, >Beginnings of The Eternal Road<, in: T"he Etemal Road (New York 1937 - programme-book for the production by MWW and Crosby Gaige at the Man hattan Opera House), pp. -

A Heretic in the Schoenberg Circle: Roberto Gerhard's First Engagement with Twelve-Tone Procedures in Andantino

Twentieth-Century Music 16/3, 557–588 © Cambridge University Press 2019. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. doi: 10.1017/S1478572219000306 A Heretic in the Schoenberg Circle: Roberto Gerhard’s First Engagement with Twelve-Tone Procedures in Andantino DIEGO ALONSO TOMÁS Abstract Shortly before finishing his studies with Arnold Schoenberg, Roberto Gerhard composed Andantino,a short piece in which he used for the first time a compositional technique for the systematic circu- lation of all pitch classes in both the melodic and the harmonic dimensions of the music. He mod- elled this technique on the tri-tetrachordal procedure in Schoenberg’s Prelude from the Suite for Piano, Op. 25 but, unlike his teacher, Gerhard treated the tetrachords as internally unordered pitch-class collections. This decision was possibly encouraged by his exposure from the mid- 1920s onwards to Josef Matthias Hauer’s writings on ‘trope theory’. Although rarely discussed by scholars, Andantino occupies a special place in Gerhard’s creative output for being his first attempt at ‘twelve-tone composition’ and foreshadowing the permutation techniques that would become a distinctive feature of his later serial compositions. This article analyses Andantino within the context of the early history of twelve-tone music and theory. How well I do remember our Berlin days, what a couple we made, you and I; you (at that time) the anti-Schoenberguian [sic], or the very reluctant Schoenberguian, and I, the non-conformist, or the Schoenberguian malgré moi. -

View Becomes New." Anton Webern to Arnold Schoenberg, November, 25, 1927

J & J LUBRANO MUSIC ANTIQUARIANS Catalogue 74 The Collection of Jacob Lateiner Part VI ARNOLD SCHOENBERG 1874-1951 ALBAN BERG 1885-1935 ANTON WEBERN 1883-1945 6 Waterford Way, Syosset NY 11791 USA Telephone 561-922-2192 [email protected] www.lubranomusic.com CONDITIONS OF SALE Please order by catalogue name (or number) and either item number and title or inventory number (found in parentheses preceding each item’s price). To avoid disappointment, we suggest either an e-mail or telephone call to reserve items of special interest. Orders may also be placed through our secure website by entering the inventory numbers of desired items in the SEARCH box at the upper left of our homepage. Libraries may receive deferred billing upon request. Prices in this catalogue are net. Postage and insurance are additional. An 8.625% sales tax will be added to the invoices of New York State residents. International customers are asked to kindly remit in U.S. funds (drawn on a U.S. bank), by international money order, by electronic funds transfer (EFT) or automated clearing house (ACH) payment, inclusive of all bank charges. If remitting by EFT, please send payment to: TD Bank, N.A., Wilmington, DE ABA 0311-0126-6, SWIFT NRTHUS33, Account 4282381923 If remitting by ACH, please send payment to: TD Bank, 6340 Northern Boulevard, East Norwich, NY 11732 USA ABA 026013673, Account 4282381923 All items remain the property of J & J Lubrano Music Antiquarians LLC until paid for in full. Fine Items & Collections Purchased Please visit our website at www.lubranomusic.com where you will find full descriptions and illustrations of all items Members Antiquarians Booksellers’ Association of America International League of Antiquarian Booksellers Professional Autograph Dealers’ Association Music Library Association American Musicological Society Society of Dance History Scholars &c. -

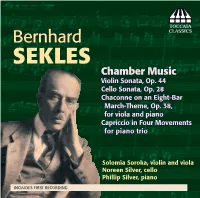

Toccata Classics TOCC0147 Notes

TOCCATA Bernhard CLASSICS SEKLES Chamber Music Violin Sonata, Op. 44 Cello Sonata, Op. 28 Chaconne on an Eight-Bar March-Theme, Op. 38, for viola and piano ℗ Capriccio in Four Movements for piano trio Solomia Soroka, violin and viola Noreen Silver, cello Phillip Silver, piano INCLUDES FIRST RECORDING REDISCOVERING BERNHARD SEKLES by Phillip Silver he present-day obscurity of Bernhard Sekles illustrates how porous is contemporary knowledge of twentieth-century music: during his lifetime Sekles was prominent as teacher, administrator and composer alike. History has accorded him footnote status in two of these areas of endeavour: as an educator with an enviable list of students, and as the Director of the Hoch Conservatory in Frankfurt from 923 to 933. During that period he established an opera school, much expanded the area of early-childhood music-education and, most notoriously, in 928 established the world’s irst academic class in jazz studies, a decision which unleashed a storm of controversy and protest from nationalist and fascist quarters. But Sekles was also a composer, a very good one whose music is imbued with a considerable dose of the unexpected; it is traditional without being derivative. He had the unenviable position of spending the prime of his life in a nation irst rent by war and then enmeshed in a grotesque and ultimately suicidal battle between the warring political ideologies that paved the way for the Nazi take-over of 933. he banning of his music by the Nazis and its subsequent inability to re-establish itself in the repertoire has obscured the fact that, dating back to at least 99, the integration of jazz elements in his works marks him as one of the irst European composers to use this emerging art-form within a formal classical structure. -

Myth in 300 Strokes

22 S TUDIA MYTHOLOGICA SLAVICA 2019 107 – 119 | DOI: 10.3987/SMS20192205 Myth in 300 Strokes Gregor Pobežin, Igor Grdina This paper aims to explore the phenomenon of the opera minute which emerged from the avant-garde experimentalism after WWI; its beginner and one of the foremost masters, the French composer Darius Milhaud put three short, eight-minute operas on stage in 1927. Others soon followed, among them the Slovenian composer Slavko Osterc who composed the opera-minute “Medea” in 1932. This paper is the first to transcribe in length the manuscript of Osterc’s “Medea”, comparing it to Euripides’ original. Furthermore, the article aims to establish the fine similarities and distinctions between the approach regular opera took towards myth and that of the avant-garde opera-minute. KEYWORDS: Miniature opera, Darius Milhaud, Slavko Osterc, Medea, myth, avant-garde INTRODUCTION While opera took shape in the late 16th century in a coincidental manner – so to speak – as a historical adaptation of the ancient tragedy, its one-minute version, the miniature opera,1 emerged after WWI from the spirit of the avant-garde experimentalism; the first impulse of its birth came from the desire to shock. Darius Milhaud who first mastered the one-minute opera wrote in his memoirs entitled Ma vie heureuse: “Between 1922 and 1932, Paul Hindemith was organizing concerts of contemporary music, first at Donaueschingen under the patronage of the Prince of Fürstenberg, and then in Baden-Baden under the auspices of the municipal authorities, and finally in 1930 in Berlin. Hindemith was absolutely his own master, and tried out all kinds of musical experiments. -

The Conclusion of Lulu, Act II

Octatonic Formations, Motivic Correspondences, and Symbolism in Alwa’s Hymne: The Conclusion of Lulu, Act II Master’s Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Department of Musicology Allan Keiler, Advisor In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Master’s of Fine Arts Degree by Alexander G. Lane May 2010 ABSTRACT Octatonic Formations, Motivic Correspondences, and Symbolism in Alwa’s Hymne: The Conclusion of Lulu, Act II A thesis presented to the Department of Musicology Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Waltham, Massachusetts By Alexander G. Lane In this study of the final number from Act II of Alban Berg’s Lulu, I examine Alwa’s Hymne from three different perspectives. First, I analyze the Hymne as if it were a free-standing composition. In this portion of the paper, I enumerate the tone-rows and motives out of which the Hymne is constructed and I discuss how these basic materials are related to each other. I place special emphasis on the multiple roles which the octatonic collection plays in this number: it functions as a subset of twelve-note formations, as a superset encompassing shorter motives, and as an agent of harmonic and melodic coherence in those sections of the Hymne that are not governed by twelve-tone sets. In this part of the paper, I also discuss the ways in which the text and the music of the Hymne may help to clarify the nature of Alwa’s relationship with Lulu. In the second section of this study, I examine the Hymne’s relation to other parts of the Lulu. -

Miriam Gideon's Cantata, the Habitable Earth

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Major Papers Graduate School 2003 Miriam Gideon's cantata, The aH bitable Earth: a conductor's analysis Stella Panayotova Bonilla Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Bonilla, Stella Panayotova, "Miriam Gideon's cantata, The aH bitable Earth: a conductor's analysis" (2003). LSU Major Papers. 20. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers/20 This Major Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Major Papers by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MIRIAM GIDEON’S CANTATA, THE HABITABLE EARTH: A CONDUCTOR’S ANALYSIS A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Stella Panayotova Bonilla B.M., State Academy of Music, Sofia, Bulgaria, 1991 M.M., Louisiana State University, 1994 August 2003 ©Copyright 2003 Stella Panayotova Bonilla All rights reserved ii DEDICATION To you mom, and to the memory of my beloved father. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thanks to Dr. Kenneth Fulton for his guidance through the years, his faith in me and his invaluable help in accomplishing this project. Thanks to Dr. Robert Peck for his inspirational insight. Thanks to Dr. Cornelia Yarbrough and Dr. -

6.5 X 11 Double Line.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-87049-8 - The Cambridge Companion to Schoenberg Edited by Jennifer Shaw and Joseph Auner Excerpt More information 1 Introduction JENNIFER SHAW AND JOSEPH AUNER This Cambridge Companion provides an introduction to the central works, writings, and ideas of Arnold Schoenberg (1874–1951). Few would challenge the contention that Schoenberg is one of the most important figures in twentieth-century music, though whether his ulti- mate achievement or influence is for good or ill is still hotly debated. There are those champions who regard as essential his works, theories, and signature ideas such as “the emancipation of the dissonance,” and “com- position with twelve tones related only to one another,” just as there are numerous critics who would cite precisely the same evidence to argue that Schoenberg is responsible for having led music astray. No doubt many readers will take up this volume with some measure of trepidation; for concertgoers, students, and musicians, the name Schoenberg can still carry a certain negative charge. And while the music of other early modernist twentieth-century composers who have preceded Schoenberg into the ranks of the Cambridge Companions – including Debussy, Bartók, Stravinsky, and even Schoenberg’s pupil Alban Berg – could be regarded as having achieved something of a state of artistic normalcy, Schoenberg’s music for many remains beyond the pale. It is not our purpose here to bring Schoenberg in from the cold or to make him more accessible by showing that the alleged difficulty, obscurity, fractiousness, and even unlovability of his music are mistaken. On the contrary, much of his music – indeed almost all of his creative output, be it theoretical, literary, or in the visual arts – could be characterized to some degree as oppositional, critical, and unafraid of provoking discomfort. -

The Correspondence Between Arnold Schoenberg and Universal Edition

The Correspondence between Arnold Schoenberg and Universal Edition Katharina Bleier Wissenschaftszentrum Arnold Schönberg Universität für Musik und darstellende Kunst Wien Therese Muxeneder Arnold Schönberg Center, Wien ‘[…] publishers and authors cannot remain friends in the long run.’1 The first curator of Schoenberg’s archival legacy was the composer himself: throughout his life he remained an archivally gifted and visionary collector, the guardian of what is now considered an unparalleled heritage in the musical history of the last century. Its spectrum, ranging from compositions and philosophical-political, musical-aesthetic and literary-political writings, to paintings and drawings and finally to the invention of objects, illuminates a personality who as both man and artist resisted to the end the tendency to conform, a personality worth discovering not only for the indelible signature he left upon the music of his century. The Arnold Schönberg Center, established in 1998 in Vienna, is a unique repository of Schoenberg’s archival legacy2 and a cultural institution that is open to the public. The Schoenberg archive is one of the most renowned and comprehensive collections of works by a twentieth-century composer and promotes a broad spectrum of research. In addition to the archive, exhibition and concert facilities, the Center also houses the Arnold Schönberg Research Center (Wissenschaftszentrum Arnold Schönberg, Institut für Musikalische Stilforschung of the Universität für Musik und darstellende Kunst Wien). 19 ARCHIVAL NOTES Sources and Research from the Institute of Music, No. 1 (2016) © Fondazione Giorgio Cini, Venezia ISBN 9788896445136 | ISSN 2499‒832X KATHARINA BLEIER – THERESE MUXENEDER Activities at the Research Center are focused on the Viennese School, particularly in its role as a group that had a lasting influence on twentieth- century music throughout the world. -

The Strategic Half-Diminished Seventh Chord and the Emblematic Tristan Chord: a Survey from Beethoven to Berg

International Journal ofMusicology 4 . 1995 139 Mark DeVoto (Medford, Massachusetts) The Strategic Half-diminished Seventh Chord and The Emblematic Tristan Chord: A Survey from Beethoven to Berg Zusammenfassung: Der strategische halbverminderte Septakkord und der em blematische Tristan-Akkord von Beethoven bis Berg im Oberblick. Der halb verminderte Septakkord tauchte im 19. Jahrhundert als bedeutende eigen standige Hannonie und als Angelpunkt bei der chromatischen Modulation auf, bekam aber eine besondere symbolische Bedeutung durch seine Verwendung als Motiv in Wagners Tristan und Isolde. Seit der Premiere der Oper im Jahre 1865 lafit sich fast 100 Jahre lang die besondere Entfaltung des sogenannten Tristan-Akkords in dramatischen Werken veifolgen, die ihn als Emblem fUr Liebe und Tod verwenden. In Alban Bergs Lyrischer Suite und Lulu erreicht der Tristan-Akkord vielleicht seine hOchste emblematische Ausdruckskraft nach Wagner. If Wagner's Tristan und Isolde in general, and its Prelude in particular, have stood for more than a century as the defining work that liberated tonal chro maticism from its diatonic foundations of the century before it, then there is a particular focus within the entire chromatic conception that is so well known that it even has a name: the Tristan chord. This is the chord that occurs on the downbeat of the second measure of the opera. Considered enharmonically, tills chord is of course a familiar structure, described in many textbooks as a half diminished seventh chord. It is so called because it can be partitioned into a diminished triad and a minor triad; our example shows it in comparison with a minor seventh chord and an ordinary diminished seventh chord. -

Hinrich Alpers Kuss Quartett Marie-Pierre Langlamet Hanno

Hinrich Alpers Kuss Quartett Marie-Pierre Langlamet Hanno Müller-Brachmann Tehila Nini Goldstein Nabil Shehata Agata Szymczewska RUDI STEPHaN (1887–1915) CHaMBER WORKS aND SONGS 1 Groteske für Geige und Klavier (1911) 8.04 13 Liebeszauber (Friedrich Hebbel) (1914) 11.31 Hinrich Alpers piano · Agata Szymczewska violin arranged for baritone and seven stringed instruments by Hinrich Alpers (2003/2013) „Ich will Dir singen ein Hohelied…“ (1913/14) Hanno Müller-Brachmann baritone · Hinrich Alpers piano 6 poems by Gerda von Robertus for soprano and piano Kuss Quartett · Nabil Shehata double-bass 2 I. Kythere 2.09 Marie-Pierre Langlamet harp 3 II. Pantherlied 0.59 14 Mitternacht (Leo Greiner) (1904) 2.53 4 III. Abendfriede 2.08 15 Weihnachtsgefühl (Martin Greif) (1905) 2.05 5 IV. In Nachbars Garten 2.25 6 V. Glück zu Zweien 2.12 Sieben Lieder nach verschiedenen Dichtern (1913/14) 7 VI. Das Hohelied der Nacht 2.34 16 I. Sonntag (Otto Julius Bierbaum) 2.07 Tehila Nini Goldstein soprano · Hinrich Alpers piano 17 II. Pappel im Stahl (Josef Schanderl) 1.50 18 III. Dir (Hinrich Hinrichs) 2.27 8 Waldnachmittag (Maurice Reinhold von Stern) (1904) 3.10 19 IV. Ein Neues (Karl von Berlepsch) 2.58 9 Auf den Tod einer jungen Frau (Anton Lindner) (1904) 2.10 20 V. Im Einschlafen (Bruno Goetz) 4.44 10 Up de eensome Hallig (Detlev von Liliencron) (1914) 2.07 21 VI. Abendlied (Gustav Falke) 3.00 22 VII. Heimat (Richard Dehmel) 3.09 “Zwei ernste Gesänge” for baritone and piano (1913/14) Tehila Nini Goldstein soprano · Hinrich Alpers piano 11 Am Abend (Johann Christian Günther) 1.21 12 Memento vivere (Friedrich Hebbel) 3.52 Hanno Müller-Brachmann baritone · Hinrich Alpers piano 2 Musik für Sieben Saiteninstrumente in a single movement and a postlude (1912) 23 I. -

200 Da-Oz Medal

200 Da-Oz medal. 1933 forbidden to work due to "half-Jewish" status. dir. of Collegium Musicum. Concurr: 1945-58 dir. of orch; 1933 emigr. to U.K. with Jooss-ensemble, with which L.C. 1949 mem. fac. of Middlebury Composers' Conf, Middlebury, toured Eur. and U.S. 1934-37 prima ballerina, Teatro Com- Vt; summers 1952-56(7) fdr. and head, Tanglewood Study munale and Maggio Musicale Fiorentino, Florence. 1937-39 Group, Berkshire Music Cent, Tanglewood, Mass. 1961-62 resid. in Paris. 1937-38 tours of Switz. and It. in Igor Stravin- presented concerts in Fed. Repub. Ger. 1964-67 mus. dir. of sky's L'histoire du saldai, choreographed by — Hermann Scher- Ojai Fests; 1965-68 mem. nat. policy comm, Ford Found. Con- chen and Jean Cocteau. 1940-44 solo dancer, Munic. Theater, temp. Music Proj; guest lect. at major music and acad. cents, Bern. 1945-46 tours in Switz, Neth, and U.S. with Trudy incl. Eastman Sch. of Music, Univs. Hawaii, Indiana. Oregon, Schoop. 1946-47 engagement with Heinz Rosen at Munic. also Stanford Univ. and Tanglewood. I.D.'s early dissonant, Theater, Basel. 1947 to U.S. 1947-48 dance teacher. 1949 re- polyphonic style evolved into style with clear diatonic ele- turned to Fed. Repub. Ger. 1949- mem. G.D.B.A. 1949-51 solo ments. Fel: Guggenheim (1952 and 1960); Huntington Hart- dancer, Munic. Theater, Heidelberg. 1951-56 at opera house, ford (1954-58). Mem: A.S.C.A.P; Am. Musicol. Soc; Intl. Soc. Cologne: Solo dancer, 1952 choreographer for the première of for Contemp.