Evan Jones (Ed.), Intimate Voices: the Twentieth-Century String Quartet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Conclusion of Lulu, Act II

Octatonic Formations, Motivic Correspondences, and Symbolism in Alwa’s Hymne: The Conclusion of Lulu, Act II Master’s Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Department of Musicology Allan Keiler, Advisor In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Master’s of Fine Arts Degree by Alexander G. Lane May 2010 ABSTRACT Octatonic Formations, Motivic Correspondences, and Symbolism in Alwa’s Hymne: The Conclusion of Lulu, Act II A thesis presented to the Department of Musicology Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Waltham, Massachusetts By Alexander G. Lane In this study of the final number from Act II of Alban Berg’s Lulu, I examine Alwa’s Hymne from three different perspectives. First, I analyze the Hymne as if it were a free-standing composition. In this portion of the paper, I enumerate the tone-rows and motives out of which the Hymne is constructed and I discuss how these basic materials are related to each other. I place special emphasis on the multiple roles which the octatonic collection plays in this number: it functions as a subset of twelve-note formations, as a superset encompassing shorter motives, and as an agent of harmonic and melodic coherence in those sections of the Hymne that are not governed by twelve-tone sets. In this part of the paper, I also discuss the ways in which the text and the music of the Hymne may help to clarify the nature of Alwa’s relationship with Lulu. In the second section of this study, I examine the Hymne’s relation to other parts of the Lulu. -

The Strategic Half-Diminished Seventh Chord and the Emblematic Tristan Chord: a Survey from Beethoven to Berg

International Journal ofMusicology 4 . 1995 139 Mark DeVoto (Medford, Massachusetts) The Strategic Half-diminished Seventh Chord and The Emblematic Tristan Chord: A Survey from Beethoven to Berg Zusammenfassung: Der strategische halbverminderte Septakkord und der em blematische Tristan-Akkord von Beethoven bis Berg im Oberblick. Der halb verminderte Septakkord tauchte im 19. Jahrhundert als bedeutende eigen standige Hannonie und als Angelpunkt bei der chromatischen Modulation auf, bekam aber eine besondere symbolische Bedeutung durch seine Verwendung als Motiv in Wagners Tristan und Isolde. Seit der Premiere der Oper im Jahre 1865 lafit sich fast 100 Jahre lang die besondere Entfaltung des sogenannten Tristan-Akkords in dramatischen Werken veifolgen, die ihn als Emblem fUr Liebe und Tod verwenden. In Alban Bergs Lyrischer Suite und Lulu erreicht der Tristan-Akkord vielleicht seine hOchste emblematische Ausdruckskraft nach Wagner. If Wagner's Tristan und Isolde in general, and its Prelude in particular, have stood for more than a century as the defining work that liberated tonal chro maticism from its diatonic foundations of the century before it, then there is a particular focus within the entire chromatic conception that is so well known that it even has a name: the Tristan chord. This is the chord that occurs on the downbeat of the second measure of the opera. Considered enharmonically, tills chord is of course a familiar structure, described in many textbooks as a half diminished seventh chord. It is so called because it can be partitioned into a diminished triad and a minor triad; our example shows it in comparison with a minor seventh chord and an ordinary diminished seventh chord. -

Tradition As Muse Schoenberg's Musical Morphology and Nascent

Tradition as Muse Schoenberg's Musical Morphology and Nascent Dodecaphony by Áine Heneghan A dissertation submitted in candidacy for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy to The University of Dublin Trinity College March 2006 DECLARATION I, Áine Heneghan, declare that this thesis has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at this or any other University and that it consists entirely of my own work. I agree that the Library may lend or copy the thesis upon request, this permission covering only single copies made for study purposes, subject to normal conditions of acknowledgement. Signed __________________ Áine Heneghan March 2006 Summary of the Dissertation Tradition as Muse: Schoenberg's Musical Morphology and Nascent Dodecaphony by Áine Heneghan The University of Dublin Trinity College March 2006 This study reappraises the evolution of Arnold Schoenberg's method of composing with twelve tones by examining the interrelationship of his theoretical writings and compositional practice. Premised on the idea that theory and practice were interdependent for Schoenberg, I argue, on the one hand, that the richness and diversity of his nascent dodecaphony can be fully appreciated only in the context of the development of his musical thought and, on the other hand, that his terminological concepts—for example, Grundgestalt, 'unfolding' [Abwicklung], the distinction between Satz and Periode (sentence and period), and the differentiation of 'stable' and 'loose' construction—came about precisely because of his compositional experiments during the early 1920s. The discussion and musical analyses of selected movements from the Klavierstücke, Op. 23, the Serenade, Op. 24, and the Suite für Klavier, Op. -

ZEMLINSKY BERG 63:53 (1871-1942) (1885-1935) Lyric Symphony, Three Pieces from the Lyric Symphony Op

CMYK NAXOS NAXOS Alexander von Zemlinsky’s best known work, the seductive Lyric Symphony, inspired Alban Berg, who quoted its third movement in his own Lyric Suite, three movements of which Berg himself arranged for string orchestra. Described by Theodor Adorno as “a latent opera”, Berg’s masterpiece was publicly dedicated to Zemlinsky but carried a secret programme: his illicit love for Hanna Fuchs-Robettin. Zemlinsky’s richly scored symphony, a late-Romantic song cycle by DDD ZEMLINKSY: ZEMLINKSY: any other name, recalls both Mahler’s Song of the Earth (8.550933) and Schoenberg’s Gurre- ZEMLINKSY: Lieder (8.557518-19). 8.572048 Alexander von Alban Playing Time ZEMLINSKY BERG 63:53 (1871-1942) (1885-1935) Lyric Symphony, Three Pieces from the Lyric Symphony Lyric Op. 18 (1923) 46:27 Lyric Suite (arr. for Symphony Lyric 1 I. Ich bin friedlos 1 – 11:13 string orchestra) (1929) 17:26 2 II. Mutter, der junge Prinz 2 – 6:30 8 I. Andante amoroso (II) 6:22 3 III. Du bist die Abendwolke 1 – 6:06 9 II. Allegro misterioso (III) 3:38 4 IV. Sprich zu mir, Geliebter 2 – 7:39 0 III. Adagio appassionato (IV) 7:26 5 V. Befrei’ mich von www.naxos.com Disc made in Canada. Printed and assembled USA. Booklet notes in English ൿ den Banden 1 – 2:07 & 6 VI. Vollende denn das Ꭿ letzte Lied 2 – 4:33 2009 Naxos Rights International Ltd. 7 VII. Friede, mein Herz 1 8:20 Roman Trekel, Baritone 1 • Twyla Robinson, Soprano 2 Houston Symphony • Hans Graf Recorded at the Jesse H. -

CHAN 9999 BOOK.Qxd 10/5/07 3:38 Pm Page 2

CHAN 9999 front.qxd 10/5/07 3:31 pm Page 1 CHANDOS CHAN 9999 CHAN 9999 BOOK.qxd 10/5/07 3:38 pm Page 2 Alban Berg (1885–1935) Complete Chamber Music String Quartet, Op. 3 (1909–10) 25:53 1 I Langsam 10:18 2 II Mäßige Viertel 10:59 premiere recording 3 Hier ist Friede, Op. 4 No. 5 (1912)* 4:34 from Altenberg Lieder arranged for piano, harmonium, violin and cello by Alban Berg (1917) Ziemlich langsam premiere recording Four Pieces, Op. 5 (1913) 8:02 for clarinet and piano arranged for viola and piano by Henk Guittart (1992) 4 I Mäßig 1:28 5 II Sehr langsam 2:08 6 III Sehr rasch 1:19 7 IV Langsam 3:05 8 Adagio* 13:13 Alban Berg, c. 1925 Second movement from the Chamber Concerto for piano, violin and 13 wind instruments (1923–25) arranged for violin, clarinet and piano by Alban Berg (1935) 3 CHAN 9999 BOOK.qxd 10/5/07 3:38 pm Page 4 Berg: Complete Chamber Music Lyric Suite (1925–26) 28:41 With the exception of the Lyric Suite and the writing songs for performance by and within for string quartet Chamber Concerto, all the works on the the family. Writing to the publisher Emil 9 Allegretto giovale 3:08 present CD were written in the three years Hertzka in 1910, Schoenberg observed: from 1910 to 1913, when Alban Berg [Alban Berg] is an extraordinarily gifted composer, 10 Andante amoroso 6:15 (1885–1935) was in his mid-twenties. but the state he was in when he came to me was 11 Allegro misterioso – Trio estatico 3:24 The earliest work, the String Quartet, Op. -

2316 Second Viennese School

Course Code: MU2316 0.5 Status: Option (Honours) Value: Title: The Second Viennese School Availability: Autumn or Spring Prerequisite: None Recommended: None Co-ordinator: Professor Jim Samson Course Staff: Professor Jim Samson This course will: Aims: • contextualise the achievement of the Second Viennese School within music history and cultural modernism • explain the special workings of serialism, including invariance, combinatorial method, permutations and troping • examine the serial music of all three composers as species of Neo-Classicism • evaluate the Schoenberg legacy By the end of this course students should: Learning Outcomes: • understand something of the complex relation between compositional and contextual histories of music • have a basic knowledge of the particular configuration of Viennese modernism, and of the reciprocity between music and the other arts • have a clear grasp of the technical workings of the twelve-note method, and of the different uses of it made by Schoenberg, Berg and Webern • be in a position to trace some of the lines connecting Schoenberg’s music to the new music of the 1950s and 1960s, and to the music of today The course will include the following: Course Content: • An account of the nineteenth- and early twentieth-century background, including the construction of a German tradition, the sidelining of Vienna by German nationalism, and the Jewish character of Viennese modernism. • The tonal music of the three composers approached by way of close-to-the text analyses of the styles and structures of certain key works, notably the first two string quartets of Schoenberg and the Piano Sonata of Berg. The declining structural weight of tonality and the gradual emergence of alternative constructive methods. -

Schoenberg and Weill

Schoenberg and Weill DAVID DREW UNTIL recently, there were only three sources to which students interested in the relationship-if any- between Weill and Schoenberg could safely be referred: Weill's published writings, 1 his music,2 and Schoenberg's gloss on a Feuilletonitem by Weill :'~ To these sources might be added a few scraps of more-or-less reliable hearsay. The first source remains the largest, and although it is no longer the most revealing, it serves an indispensable purpose. References to Schoenberg in Weill's contributions to the Berlin radio journal Der deutsche Rundfunk during the crucial years 1925-7 are quite numerous and uniformly positive, whether his subject be the. composer of Gurrelieder or of Pierrot Lunaire. 'Selbst seine Gegner', he wrote in the issue of 28 February 1926, 'mtissen in ihm die reinste, edelste KtinstlerpersonaliUit und die starkste Geistigkeit des heutigen Musiklebens anerkennen.' [Even his opponents have to recognise in him the purest and most noble artistic personality and the strongest mind in today's musicallife.J4 No such awe informs the handful of published references to Schoenberg that Weill permitted himselfin his Broadway years. Nevertheless, one trace of the early attitude survives in an inverted form: whereas the Weill ofFebruary 1926lauded a Schoenberg 'der einen Erfolg zu Lebzeiten fast als einen Ruckschritt seiner Kunst betrachtet' [who regards success in his own lifetime almost as a setback for his art], the Weill of 1940 declared that whereas he himself composed 'for today' and didn't 'give a damn for pos terity', Schoenberg wrote 'for a time 50 years after his death'.5 Merely attributed to Weill by the writer of a newspaper article - and indebted, perhaps, to a view of posterity already offered to the American public by Stravinsky - Weill's most celebra ted aperPJ fulfills a need but lacks a context. -

Four Pieces for Clarinet & Piano in Fin De Siècle Europe, As Tonality Was

Four Pieces for clarinet & piano In fin de siècle Europe, as tonality was becoming subordinate to increasing use of chromaticism and key signatures began disappearing form the works of prominent composers, the concept of “maximization of the minimum” was manifesting itself in music. Anton Webern, widely recognized for his compositions of “supreme brevity”, along with his teacher Arnold Schoenberg and colleague Alban Berg, experimented with composition on the micro scale. Just as Schoenberg’s abandonment of key signatures in 1908 symbolized reaction against common practice tonality, so to was the lean towards musical compression a reaction against the superfluous repetition of the Romantic era – and both shifts occurred during a time when the world was experiencing similar tumult and uncertainty. Schoenberg declared, “we shouldn’t have repetition”, reinforcing the concept “less is more”, and his Pierrot Lunaire is a masterpiece of short forms, as is Webern’s Three Little Pieces for Cello and Piano. Both exemplify extreme conciseness within the context of free atonality and these miniatures serve as microcosms of the composers’ overall style as is present in their larger works. Berg’s perspective on the “Art of the miniature” exists in his Four Pieces for Clarinet and Piano, Op. 5. While it is the only piece in his output to explore short forms, this composition is brimming with elements of profound expressionism (namely, sehnsucht and weltschmerz) and, despite its short duration, effortlessly conveys a turbulent emotional landscape in a manner no less effective than a much lengthier Brahms sonata. Berg was born in Vienna in 1885; although he evolved into one of the preeminent composers of the Second Viennese School, he did not begin composing until the age of 15 and was largely self-taught before becoming a student of Schoenberg in 1904. -

University Microfilms International 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 USA St

SELECTED TWENTIETH-CENTURY STRING QUARTETS: AN APPROACH TO UNDERSTANDINGSTYLE AND FORM Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Walker, Mary Beth Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 06/10/2021 13:06:11 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/290437 INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on. the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. -

Download Booklet

570401bk Franzetti:557541bk Kelemen 3+3 15/5/07 9:49 PM Page 1 Notes from the Pianist Allison Brewster Franzetti I was originally inspired to record this project after learning reigned supreme, brought to a dramatic and all-too-often A multiple GRAMMY® nominee, pianist Allison Brewster Franzetti has received international acclaim from critics and and performing Paul Hindemith’s Trauermusik, for viola tragic end by the Nazis. Schoenberg, born a Jew who audiences alike for her stunning virtuosity and musicality, both as a soloist and chamber musician. Born in New York and piano. I was so struck by the beauty of this particular converted to Protestantism and eventually back to Judaism, City, she received her Bachelor of Music degree from the Manhattan School of Music and her Master of Music degree piece that I started thinking about the lack of championship was dismissed from his post in 1933 with the passage of the from the Juilliard School. She has won first prizes from the Paderewski Foundation and the Piano Teachers Congress for so much of Hindemith’s repertoire. My husband, Carlos, racial laws which prohibited him from working. He left of New York as well as awards from the Kosciuszko Foundation and the Denver Symphony Orchestra. She was the gave me a copy of Hindemith’s Sonata No. 2 for solo piano Germany literally in order to survive and moved to the recipient of two HEART (History, Education, Arts – Reaching Thousands) Grants from the Union County Board of and suggested that I learn it. As I did so, I fell in love with United States, where he died in 1951. -

List of Compositions

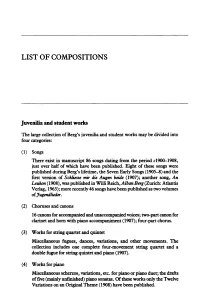

LIST OF COMPOSITIONS Juvenilia and student works The large collection of Berg's juvenilia and student works may be divided into four categories: (1) Songs There exist in manuscript 86 songs dating from the period c1900-1908, just over half of which have been published. Eight of these songs were published during Berg'S lifetime, the Seven Early Songs (1905-8) and the ftrst version of Schliesse mir die Augen beide (1907); another song, An Leukon (1908), was published in Willi Reich, Alban Berg (Zurich: Atlantis Verlag, 1963); more recently 46 songs have been published as two volumes ofJugendlieder. (2) Choruses and canons 16 canons for accompanied and unaccompanied voices; two-part canon for clarinet and hom with piano accompaniment (1907); four-part chorus. (3) Works for string quartet and quintet Miscellaneous fugues, dances, variations, and other movements. The collection includes one. complete four-movement string quartet and a double fugue for string quintet and piano (1907). (4) Works for piano Miscellaneous scherzos, variations, etc. for piano or piano duet; the drafts of ftve (mainly unfmished) piano sonatas. Of these works only the Twelve Variations on an Original Theme (1908) have been published. 292 THE BERG COMPANION All of the unpublished works should appear in the near future as part of the forthcoming Alb~ Berg Gesamtmugabe. Published works Jugendlieder, vol. 1(1901-4),23 selected songs for voice and piano Schliesse mir die Augen beide [1], for voice and piano (1907) Jugendlieder, vol. 2 (1904-8), 23 selected songs for voice and piano Seven Early Songs, for voice and piano (1905-8); orchestral arrangement (1928) Am Leukon, for voice and piano (1908) Twelve Variations on an Original Theme, for piano (1908) Sonata op. -

Cognitive Structure in Viennese Twelve-Tone Rows

Tonal and “Anti-Tonal” Cognitive Structure in Viennese Twelve-Tone Rows PAUL T. von HIPPEL [1] University of Texas, Austin DAVID HURON Ohio State University ABSTRACT: We show that the twelve-tone rows of Arnold Schoenberg and Anton Webern are “anti-tonal”—that is, structured to avoid or undermine listener’s tonal schemata. Compared to randomly generated rows, segments from Schoenberg’s and Webern’s rows have significantly lower fit to major and minor key profiles. The anti-tonal structure of Schoenberg’s and Webern’s rows is still evident when we statistically controlled for their preference for other row features such as mirror symmetry, derived and hexachordal structures, and preferences for certain intervals and trichords. The twelve-tone composer Alban Berg, by contrast, often wrote rows with segments that fit major or minor keys quite well. Submitted 2020 May 4; accepted 2020 June 2 Published 2020 October 22; https://doi.org/10.18061/emr.v15i1-2.7655 KEYWORDS: serialism, twelve-tone music, music cognition, tonality, tonal schema, contratonal INTRODUCTION NEARLY 100 years ago, in 1921, the Viennese composer Arnold Schoenberg developed a “method of composing with twelve tones” (Schoenberg, 1941/1950). Schoenberg’s approach began with a twelve-tone row, which assigned an order to the twelve tones of the chromatic scale. Because each “tone” could be used in any octave, it was actually what would later be called a “chroma” in psychology, or a “pitch class” in music theory. The tone row provided the basis for all of a composition’s harmonic and melodic material. In addition to using the tone row in its original, basic, or prime form, a composer could use the tone row in three derived forms: retrograde, which turned the tone row backward; inversion, which turned the tone row upside- down by inverting all its intervals; or retrograde inversion, which did both.[2] In addition, any form of the row could be transposed by moving every chroma up (or down[3]) by 1 to 11 semitones.