William Shakespeare's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

William Shakespeare's

classic repertory company STUDY GUIDE William Shakespeare’s JULIUS CAESAR Education Outreach Supporters Funded in part by generous individual contributors, the National Endowment for the Arts, Massachusetts Cultural Council, Foundation for MetroWest, Fuller Foundation, The Marshall Home Fund, Roy A. Hunt Foundation, and Watertown Community Foundation. This program is also supported in part by grants from the Billerica Arts Council, Brookline Commission for the Arts, Canton Cultural Council, Brockton Cultural Council, Lawrence Cultural Council, Lexington Council for the Arts, Marlborough Cultural Council, Newton Cultural Council, Watertown Cultural Council, and Wilmington Cultural Council, local agencies which are supported by the Massachusetts Cultural Council, a state agency. Classic Repertory Company is produced in cooperation with Boston University College of Fine Arts School of Theatre NEW REP ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICE 200 DEXTER AVENUE WATERTOWN, MA 02472 the professional theatre company in residence at the artistic director jim petosa managing director harriet sheets arsenal center for the arts A Timeline of Shakespeare’s Life 1564 Born in Stratford-upon-Avon 1582 Marries Anne Hathaway 1585 Moves to London to pursue theatre career 1592 London closes theatres due to plague 1593 Starts to write sonnets 1594 Publishes first works of poetry 1594 Starts managing, as well as writing for, the Lord Chamberlain’s Men 1599 Writes Julius Caesar 1600 Writes Hamlet, one of his most well-known plays 1603 The Lord Chamberlain’s Men is renamed the King’s Men in honor of the new King James’ patronage 1604 Retires from acting 1613 The Globe Theatre burns down 1614 The Globe Theatre is rebuilt 1616 Dies and is buried at Holy Trinity Church in Stratford-Upon-Avon adapted from http://absoluteshakespeare.com/trivia/timeline.htm C.1600 JOHN TAYLOR THE CHANDOS PORTRAIT, LONDON PORTRAIT GALLERY, NATIONAL Why do we read Shakespeare? Shakespeare’s works are over 400 years old. -

Dylan Arredondo

DYLAN ARREDONDO [email protected] www.DylanArredondo.com Height: 6’2’’ Hair Color: Black Eye Color: Brown Non-Union THEATRE Snow Queen (Upcoming) Ensemble Synetic Theater/Dir. Ryan Sellers Lady from the Village of Falling Emperor Nijo Provincetown Tennessee Williams Theatre Festival & Flowers Spooky Action Theatre/Dir. Natsu Onoda Power American Spies… Tamihei/Buzzard The Hub/Dir. Kathryn Chase Bryer The White Snake Ensemble/Xu Xian (u/s) Constellation/Dir. Allison Stockman Tigers, Dragons & Other Wise Tails Thief/Rich Man/Mole Smithsonian’s Discovery/Dir. Roberta Gasbarre Reykjavik Martin/Ross/Robert Rorschach/Dir. Rick Hammerly Seasons of Light Featured Ensemble Smithsonian’s Discovery/Dir. Roberta Gasbarre The Interstellar Ghost Hour Chef Longacre Lea/Dir. Kathleen Akerley The Great Gatsby Tom Buchanan National Players, Olney Theatre Center (OTC) Dir. Amber Paige McGinnis Othello Cassio National Players, OTC/Dir. Jason King Jones Alice in Wonderland Caterpillar/Ensemble National Players, OTC/Dir. Natsu Onoda Power The Merchant of Venice Bassanio Hamlet Isn’t Dead/Dir. David Andrew Laws #serials at the Flea Various Roles The Flea/Dir. Various* Little Invisible Backpacks Dad Midtown International Fesitval/Dir. Magda Cychowski The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui Clark/Dockdaisy/Dullfeet Cave Theatre Co./Dir. James Masciovecchio Love, Chekhov, & the Magic Trunk Smirnoff/Zhigalov F2T’s Company/Dir. Fotis Batzas The Tempest Prospero The Brick/Dir. Ilana Khanin All’s Well That Ends Well Widow/Steward Shakespeare in the Square (SITS)/Dir. Dan Hasse Much Ado About Nothing Leonato SITS/Dir. Arianna Chang A Midsummer Night’s Dream Demetrius/Flute Cue for Passion Collaborative/Dir. Peter Molesworth Henry V King Henry SITS/Dir. -

National Players Tour 57

TOUR 63 Presenter Press Book Dear Presenter of the National Players 63rd Tour: This is your Press Book, containing complete program copy and information to help you with your Presentation of Tour 63. Please use these materials or paraphrase as you see fit. Any information that MUST be included in your program is notated as such. The company may be available, when in your area, for interviews. Please call Madeleine Russell, General Manager at 301.924.4485 x116 to make arrangements or if you have any questions. The following division of the Press Book should enable you to find what you might need: The Taming of the Shrew by William Shakespeare Cast List and Credits Director’s Notes Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck Cast List and Credits Director’s Notes National Players Information Company Biographies Director and Designer Biographies Olney Theatre Center Staff Listing A History of National Players On all programs, the following information must appear: National Players is a program of Olney Theatre Center. Olney Theatre Center is funded by an operating grant from the Maryland State Arts Council, an agency dedicated to cultivating a vibrant cultural community where the arts thrive. Funding for the Maryland State Arts Council is also provided by the National Endowment for the Arts, a federal agency, which believes that a great nation deserves great art. 2 The Taming of the Shrew by William Shakespeare Directed by Clay Hopper, Associate Artistic Director Jim Petosa Amy Marshall Artistic Director Managing Director Set Design Costume Design Lighting Design Sound Design Meaghan Toohey Ivania Stack Sonya Dowhaluk Christopher Baine Actor Coach Performance Consultant Halo Wines William H. -

Julius Caesar

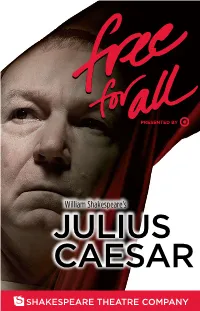

PRESENTED BY William Shakespeare's JULIUS CAESAR SHAKESPEARE THEATRE COMPANY Dear Friend, "i thank you for your pains and courtesy". Table of Contents I hope you will enjoy one of Julius Caesar, act 2, scene 2 Letter from Michael Kahn 3 Shakespeare’s most politically Out of the Past charged pieces, uniquely suited by Akiva Fox 4 to Washington, D.C., audiences. Synopsis 7 Julius Caesar reaches into the ThE 2011 ShakESPEaRE ThEaTRE ComPaNY About the Playwright 9 heart of Roman history to explore not only the consequences of Title Page 11 FREE FoR all iS PRESENTED BY conspiracy but also the complications of political Cast 12 ambition. David Muse’s original 2008 production Cast Biographies 13 was called “majestic” by the Washington Times and hailed as “electrifying” by DC Theatre Review. Direction and Design Biographies 21 I am pleased to make this wonderful production available to the Washington community for free, Shakespeare: with the generous support of sponsors like Target Caesar of Playwrights? 26 and donors like the Friends of Free For All. Shakespeare Theatre Company There could be no greater gift on the eve of this Board of Trustees 6 anniversary season than to celebrate its opening Shakespeare Theatre with you—friends new and old. I hope you will Company 24 return during the 2011-2012 Season to experience some of the exciting events we have in store. This Friends of Free For All 28 Ad Space season is sure to bring many memorable moments For the Shakespeare to STC stages, from the classic works of Regnard, Theatre Company 30 O’Neill and Goldoni to Shakespeare’s Much Ado Staff 32 About Nothing, The Two Gentlemen of Verona Happenings 33 and The Merry Wives of Windsor. -

2021 Program Book

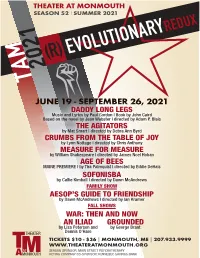

THEATER AT MONMOUTH SEASON 52 I SUMMER 2021 EDUX IONARYR EVOLUT M (R) 2021 TA JUNE 19 - SEPTEMBER 26, 2021 DADDY LONG LEGS Music and Lyrics by Paul Gordon I Book by John Caird Based on the novel by Jean Webster I directed by Adam P. Blais THE AGITATORS by Mat Smart I directed by Debra Ann Byrd CRUMBS FROM THE TABLE OF JOY by Lynn Nottage I directed by Chris Anthony MEASURE FOR MEASURE by William Shakespeare I directed by James Noel Hoban AGE OF BEES MAINE PREMIERE I by Tira Palmquist I directed by Eddie DeHais SOFONISBA by Callie Kimball I directed by Dawn McAndrews FAMILY SHOW AESOP’S GUIDE TO FRIENDSHIP by Dawn McAndrews I directed by Ian Kramer FALL SHOWS WAR: THEN AND NOW AN ILIAD GROUNDED by Lisa Peterson and by George Brant THEATER Dennis O’Hare TICKETS $10 - $36 | MONMOUTH, ME | 207.933.9999 T WWW.THEATERATMONMOUTH.ORG MAT SEASON SPONSOR: MAIN STREET PSYCHOTHERAPY AMONMOUTH ACTING COMPANY CO-SPONSOR: KENNEBEC SAVINGS BANK W e are proud to support the Theater at M onm outh Enjoy the show ! Augusta (207) 622-5801 Farmingdale (207) 588-5801 • Freeport (207) 865-1550 Winthrop (207) 377-5801 • Waterville (207) 872-5563 www.KennebecSavings.Bank Maine’s Black Business Directory BOM Podcast BIPOC Mutual Aid Business Incubator Marketing and blackownedmaine.com Advertising @blackownedmaine E business cards | posters L B presentation folders newsletters | reports IA L labels | booklets | envelopes postcards | banners | menus RE • rack cards | brochures | forms promotional items | lawn signs ST laminating | letterhead | foam core A F tabs | scanning | post it note pads £Ç7iÃÌwi`-ÌÀiiÌ • *ÀÌ>`] ä{£äÓ booklets | calendars | invitations L 207.775.2444 manuals | handouts | binding A orders @xcopy.com C direct mailings | legal briefs | blueprints WWW.XCOPY.COM O AND MORE! L 4 | THEATER AT MONMOUTH SEASON 52 REVOLUTIONARY REDUX TABLE OF CONTENTS DADDY LONG LEGS Music and Lyrics by Paul Gordon Book by John Caird About Theater at Monmouth 6 Based on the novel by Jean Webster | directed by Adam P. -

© in This Web Service Cambridge University

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-49709-2 - The Cambridge History of British Theatre: Volume 3: Since 1895 Edited by Baz Kershaw Index More information Index Note: Italicised page numbers refer to illustrations. Abbey Theatre, 24, 69, 198, 201 ACW(Arts Council of Wales), 486–9 Abbey Theatre Company, 53 adaptations, 435 ABCA (Army Bureau of Current Affairs), 294, Adding Machine, The, 132 352–3 Adelphi Players, 354 Abraham Lincoln, 158 Admirable Crichton, The, 43, 72 ABSA (Association for Business Sponsorship Adult Education Committee (1926), 133–4 of the Arts), 348, 381 Adwaith, 268 Abse, Dannie, 244 afterpieces, 98, 99 Absence of War, The, 319, 419 After the Orgy, Absent Friends, 310 Agate, James, 45, 116, 131, 148, 157 absurd, theatre of, 337–40, 372 Age of Empire, 58–9 Absurd Person Singular, 345 Age Exchange, 369 Accidental Death of an Anarchist, 310 agitational propaganda (agit prop), 26, Achurch, Janet, 170 176–9 Ac Eto Nid Myfi, 258 Alabama Minstrels, 100 Acis and Galatea, 17 Albert, Prince, 4 Ackland, Rodney, 166 Albery, Bronson, 149 Act of Union, 197 Albery, Donald, 302 Actor and the Uber-Marionette,¨ the, 190 Albery, Ian, 310 actor-manager system, 5–6 Aldwych Theatre, 149, 335 decline of, 11 Alexander, George, 7 historical views of, 6 as actor-manager, 38, 39 and rise in social position of performers, 7 knighthood of, 37 actors, 382–3 repertoire, 65 contracts, 387 as society actor, 8 control of Shakespearean productions, 31–2 success in provincial theatres, 63, 66 earnings, 387 Alexander Marsh Company, 66 employment, 386–7 -

TO KILL a MOCKINGBIRD Directed by CLAY HOPPER

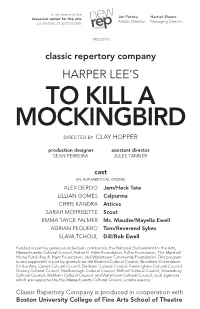

in residence at the Jim Petosa Harriet Sheets mosesian center for the arts Artistic Director Managing Director 321 ARSENAL ST, WATERTOWN PRESENTS classic repertory company HARPER LEE’S TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD DIRECTED BY CLAY HOPPER production designer assistant director SEAN PERREIRA JULES TANNER cast (IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER) ALEX DEROO Jem/Heck Tate LILLIAN GOMES Calpurnia CHRIS KANDRA Atticus SARAH MORRISETTE Scout EMMA TAYCE PALMER Ms. Maudie/Mayella Ewell ADRIAN PEGUERO Tom/Reverend Sykes SLAVA TCHOUL Dill/Bob Ewell Funded in part by generous individual contributors, the National Endowment for the Arts, Massachusetts Cultural Council, Esther B. Kahn Foundation, Fuller Foundation, The Marshall Home Fund, Roy A. Hunt Foundation, and Watertown Community Foundation. This program is also supported in part by grants from the Boxford Cultural Council, Brookline Commission for the Arts, Carver Cultural Council, Dedham Cultural Council, Framingham Cultural Council, Granby Cultural Council, Marlborough Cultural Council, Milford Cultural Council, Shrewsbury Cultural Council, Waltham Cultural Council, and Watertown Cultural Council, local agencies which are supported by the Massachusetts Cultural Council, a state agency. Classic Repertory Company is produced in cooperation with Boston University College of Fine Arts School of Theatre ALEX DEROO (Jem/Heck Tate) makes his her love of storytelling from many points of view. New Repertory Theatre debut. Emma has trained in both contemporary and Alex graduated from Salem State classical acting at the Guthrie, Boston University, University in 2016 with a BFA and the London Academy of Music and Dramatic in Theatre Performance. He is Art (LAMDA). Recent credits include Tanya in originally from Reading, MA. Recent credits Punk Rock and Dunyasha in The Cherry Orchard. -

OTHELLO Directed by CLAY HOPPER

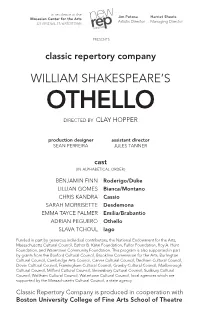

in residence at the Jim Petosa Harriet Sheets Mosesian Center for the Arts Artistic Director Managing Director 321 ARSENAL ST, WATERTOWN PRESENTS classic repertory company WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE’S OTHELLO DIRECTED BY CLAY HOPPER production designer assistant director SEAN PERREIRA JULES TANNER cast (IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER) BENJAMIN FINN Roderigo/Duke LILLIAN GOMES Bianca/Montano CHRIS KANDRA Cassio SARAH MORRISETTE Desdemona EMMA TAYCE PALMER Emilia/Brabantio ADRIAN PEGUERO Othello SLAVA TCHOUL Iago Funded in part by generous individual contributors, the National Endowment for the Arts, Massachusetts Cultural Council, Esther B. Kahn Foundation, Fuller Foundation, Roy A. Hunt Foundation, and Watertown Community Foundation. This program is also supported in part by grants from the Boxford Cultural Council, Brookline Commission for the Arts, Burlington Cultural Council, Cambridge Arts Council, Carver Cultural Council, Dedham Cultural Council, Dover Cultural Council, Framingham Cultural Council, Granby Cultural Council, Marlborough Cultural Council, Milford Cultural Council, Shrewsbury Cultural Council, Sudbury Cultural Council, Waltham Cultural Council, Watertown Cultural Council, local agencies which are supported by the Massachusetts Cultural Council, a state agency. Classic Repertory Company is produced in cooperation with Boston University College of Fine Arts School of Theatre BENJAMIN FINN (Roderigo/Duke)makes his diverse artistic community that cultivated her love New Repertory Theatre acting debut. of storytelling from many points of view. Emma has Ben recently graduated from UMass trained in both contemporary and classical acting Amherst with a double major BA in at the Guthrie, Boston University, and the London Theatre and English, and had worked Academy of Music and Dramatic Art (LAMDA). at New Rep for two full seasons as Recent credits include Tanya in Punk Rock and a Production Assistant prior to performing on Dunyasha in The Cherry Orchard. -

Classic Repertory Company STUDY GUIDE William Shakespeare’S ROMEO and JULIET

classic repertory company STUDY GUIDE William Shakespeare’s ROMEO AND JULIET Education Outreach Supporters Funded in part by generous individual contributors, the National Endowment for the Arts, Massachusetts Cultural Council, Foundation for MetroWest, Esther B. Kahn Foundation, Fuller Foundation, The Marshall Home Fund, Roy A. Hunt Foundation, and Watertown Community Foundation. This program is also supported in part by grants from the Brookline Commission for the Arts, Cambridge Arts Council, Greenfield Cultural Council, Marlborough Cultural Council, Plymouth Cultural Council, and Watertown Cultural Council, local agencies which are supported by the Massachusetts Cultural Council, a state agency. Classic Repertory Company is produced in cooperation with Boston University College of Fine Arts School of Theatre NEW REP administratiVE OFFICE 200 DEXTER AVENUE WATERTOWN, MA 02472 the professional theatre company in residence at the artistic director jim petosa managing director harriet sheets arsenal center for the arts A Timeline of Shakespeare’s Life 1564 Born in Stratford-upon-Avon 1582 Marries Anne Hathaway 1585 Moves to London to pursue theatre career 1592 London closes theatres due to plague 1593 Starts to write sonnets 1594 Publishes first works of poetry 1594 Starts managing, as well as writing for, the Lord Chamberlain’s Men 1596 Romeo and Juliet first performed .1600 .1600 C 1599 Lord Chamberlain’s Men begin performing at YLOR the newly built Globe Theater A T ONDON L N 1600 Writes Hamlet, one of his most well-known plays H 1603 The Lord Chamberlain’s Men is renamed the King’s Men in honor of the new King James’ patronage 1604 Retires from acting JO PORTRAIT, S 1613 The Globe Theatre burns down ANDO 1614 The Globe Theatre is rebuilt H E C ATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY, PORTRAIT GALLERY, ATIONAL 1616 Dies and is buried at Holy Trinity Church TH N in Stratford-Upon-Avon adapted from http://absoluteshakespeare.com/trivia/timeline.htm Why do we read Shakespeare? Shakespeare’s works are over 400 years old. -

Macbeth Study Guide.Pdf

America’s longest running touring company STUDY GUIDE 2 SUMMARY OF CURRICULUM STANDARDS The exercises and information in this study guide are geared towards fulfilling the Common Core State Standards for En- Table of Contents glish Language Arts and Literacy for Grades 11-12. Summary of Curriculum Standards...........................2 Writing About National Players .............................................3 • Write informative/explanatory texts to examine and con- vey complex ideas, concepts, and information clearly and Background: About William Shakespeare ................4 accurately through the effective selection, organization, and analysis of content. • Write narratives to develop real or imagined experiences Background: Hearing Shakespeare ..........................4 or events using effective technique, well-chosen details, and well-structured event sequences. Background: The Performance ................................5 • Produce clear and coherent writing in which the devel- opment, organization, and style are appropriate to task, Background: The Theatre .........................................5 purpose, and audience. • Develop and strengthen writing as needed by planning, Macbeth: Synopsis ...................................................6 revising, editing, rewriting, or trying a new approach, -fo cusing on addressing what is most significant for a specific Meet the Characters ................................................7 purpose and audience. • Conduct short as well as more sustained research proj- Shakespeare’s World: -

Study Guide: As You Like It

Study Guide: As You Like It Getting the most out of the Study Guide for As You Like It Our study guides are designed with you and your classroom in mind, with information and activities that can be implemented in your curriculum. National Players has a strong belief in the relationship between the actor and the audience because, without either one, there is no theatre. We hope this study guide will help bring a better understanding of the plot, themes and characters in the play so that you can more fully enjoy the theatrical experience. Feel free to copy the study guide for other teachers and for students. You may wish to cover some content before your workshops and the performance; some content is more appropriate for discussion afterwards. Of course, some activities and questions will be more useful for your class, and some less. Feel free to implement any article, activity, or post-show discussion question as you see fit. Before the Performance Using the articles in the study guide, students will be more engaged in the performance. Our articles relate information about things to look for in the show and information on Shakespeare. In addition, there are articles on the various play adaptations and movies inspired by Shakespeare work. All of this information, combined with our in-classroom workshops, will keep the students attentive and make the performance an active learning experience. After the Performance With the play as a reference point, our questions, and activities can be incorporated into your classroom discussions and can enable students to develop their higher level thinking skills. -

TEACHER TOOLKIT Tour 71, 2019-20 Table of CONTENTS

AS YOU LIKE IT TEACHER TOOLKIT Tour 71, 2019-20 Table of CONTENTS INTRODUCTION • How to use this guide.................................................................1 • Who are the National Players?...................................................2 • Life on the Road......................................................................3-4 • Offstage Roles.............................................................................5 HISTORICAL CONTEXT • Shakespeare’s World...............................................................7-8 • Shakespeare’s Language.......................................................9-10 WORLD OF THE PLAY • The Pastoral Genre.............................................................12-13 • Gender and Marriage..........................................................14-17 • Banishment.......................................................................18-19 • Getting to know Rosalind....................................................20-21 ABOUT THE SHOW • Synopsis..................................................................................23 • Character Map..........................................................................24 • An Actor’s Perspective.........................................................25-26 • A Designer’s Perspective.....................................................27-28 • Theatre Etiquette.....................................................................29 • Classroom Activities............................................................30-32 How to use this