The Leiden Collection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HNA April 11 Cover-Final.Indd

historians of netherlandish art NEWSLETTER AND REVIEW OF BOOKS Dedicated to the Study of Netherlandish, German and Franco-Flemish Art and Architecture, 1350-1750 Vol. 28, No. 1 April 2011 Jacob Cats (1741-1799), Summer Landscape, pen and brown ink and wash, 270-359 mm. Hamburger Kunsthalle. Photo: Christoph Irrgang Exhibited in “Bruegel, Rembrandt & Co. Niederländische Zeichnungen 1450-1850”, June 17 – September 11, 2011, on the occasion of the publication of Annemarie Stefes, Niederländische Zeichnungen 1450-1850, Kupferstichkabinett der Hamburger Kunsthalle (see under New Titles) HNA Newsletter, Vol. 23, No. 2, November 2006 1 historians of netherlandish art 23 S. Adelaide Avenue, Highland Park, NJ 08904 Telephone/Fax: (732) 937-8394 E-Mail: [email protected] www.hnanews.org Historians of Netherlandish Art Offi cers President - Stephanie Dickey (2009–2013) Bader Chair in Northern Baroque Art Queen’s University Kingston ON K7L 3N6 Canada Vice-President - Amy Golahny (2009–2013) Lycoming College Williamsport, PA 17701 Treasurer - Rebecca Brienen University of Miami Art & Art History Department PO Box 248106 Coral Gables FL 33124-2618 European Treasurer and Liaison - Fiona Healy Seminarstrasse 7 D-55127 Mainz Germany Board Members Contents Dagmar Eichberger (2008–2012) HNA News ............................................................................1 Wayne Franits (2009–2013) Matt Kavaler (2008–2012) Personalia ............................................................................... 2 Henry Luttikhuizen (2009 and 2010–2014) Exhibitions -

Oog in Oog Met Jan Van Mieris 24 Jaar Geduld Museum De Lakenhal Beloond

VERZAMELGEBIED GESTEUND SCHILDERKUNST 16DE EN 17DE EEUW Oog in oog met Jan van Mieris 24 jaar geduld Museum De Lakenhal beloond Het zelfportret van de Leidse fijnschilder Jan van Mieris stond al heel lang op het verlanglijstje van Museum De Lakenhal. Al in 1990 had conservator Christiaan Vogelaar een zoektocht gestart naar dit werk, waarvan de verblijfplaats niet bekend was. Uiteindelijk kwam hij bij de toenmalige eigenaren terecht: de in 2006 overleden schrijver Gerard Reve en zijn partner. Die waren echter niet van plan het schilderij te verkopen. Maar nu, na 24 jaar, is het alsnog gelukt om het begeerde werk te verwerven. Zelfportret useum De Lakenhal heeft literatuur bekend was. Na een tip gebrek aan talent heeft dat beslist niet Willem van Mieris in de loop van de jaren een kwam het uiteindelijk de eigenaren gelegen. De voortijdige dood van de ca. 1705. Olieverf op mooie verzameling aangelegd op het spoor. Dat bleken de schrijver kunstenaar, op 30-jarige leeftijd, was doek, 91,5 x 72 cm Mvan schilderijen met zelfportretten Gerard Reve en zijn partner Joop debet aan zijn geringe bekendheid. MUSEUM DE LAKENHAL, LEIDEN van Leidse kunstenaars – van de 16de- Schafthuizen te zijn. Die waren graag Jan van Mieris’ oeuvre omvat door (Aangekocht in 1990 eeuwse schilder Isaac van Swanenburg bereid de conservator te ontvangen en zijn korte leven niet meer dan een met steun van de tot Rembrandt en Jan Steen – maar de het schilderij te laten zien, maar het was dertigtal schilderijen en een enkele Vereniging Rembrandt) Leidse fijnschilders waren tot dusverre niet te koop – de missie leek mislukt. -

The Penitent Mary Magdalene Signed and Dated ‘W

Willem van Mieris (Leiden 1662 - Leiden 1747) The Penitent Mary Magdalene signed and dated ‘W. Van/Mieris/Fe/1709’ (upper left) oil on panel 20.3 x 16.2 cm (8 x 6⅜ in) In this small, exquisitely painted picture, Willem van Mieris has depicted Mary Magdalene, grief-stricken and living in the wilderness. After Christ’s crucifixion Mary was believed to have become a hermit, devoting her life to penance and prayer. Here she is seen, clearly upset, staring devoutly at a crucifix. She is instantly recognisable from the ointment jar, her bared breast, and her long flowing hair, all of which are typical aspects of her iconography. The skull is a traditional memento mori, an emblem of the transience of earthly life which serves as an aide to Mary’s meditations on Christ’s death. Willem van Mieris was perhaps the principle figure in the last generation of the fijnschilders, a group of painters based in Leiden who specialised in small scale pictures, filled with detail and defined by miniaturistic precision and refinement of technique. The two leading fijnschilders of the previous generations were Gerrit Dou (1613-1675), and Willem’s father, Frans van Mieris (1635-1681). The Penitent Mary Magdalene demonstrates that Willem had inherited the polished technique, and passion for meticulously rendered detail, that characterised the work of these masters. The foreground is a range of 125 Kensington Church Street, London W8 7LP United Kingdom www.sphinxfineart.com Telephone +44(0)20 7313 8040 Fax: +44 (0)20 7229 3259 VAT registration no 926342623 Registered in England no 06308827 contrasting textures, such as the tough, battered leather of the book, against the cold stone ledge, and these surfaces are rendered with the same painstaking care as the tear-stained puffiness of Mary’s eyes. -

ARTIST Is in Caps and Min of 6 Spaces from the Top to Fit in Before Heading

FRANS VAN MIERIS the Elder (1635 – Leiden – 1681) A Self-portrait of the Artist, bust-length, wearing a Turban crowned with a Feather, and a fur- trimmed Robe On panel, oval, 4½ x 3½ ins. (11 x 8.2 cm) Provenance: Jan van Beuningen, Amsterdam From whom purchased by Pieter de la Court van der Voort (1664-1739), Amsterdam, before 1731, for 120 Florins (“door myn vaader gekofft van Jan van Beuningen tot Amsterdam”) In Pieter de la Court van der Voort’s inventory of 1731i His son Allard de la Court van der Voort, and in his inventories of 1739ii and 1749iii His widow, Catherine de la Court van de Voort-Backer Her deceased sale, Leiden, Sam. and Joh. Luchtmans, 8 September 1766, lot 23, for 470 Florins to De Winter Gottfried Winkler, Leipzig, by 1768 Probably anonymous sale, “Twee voornamen Liefhebbers” (two distinguished amateurs), Leiden, Delfos, 26 August 1788, lot 85, (as on copper), sold for f. 65.5 to Van de Vinne M. Duval, St. Petersburg (?) and Geneva, by 1812 His sale, London, Phillips, 12 May 1846, lot 42 (as a self-portrait of the artist), sold for £525 Anonymous sale, London, Christie’s, 21 February 1903, lot 80, (as a self-portrait of the artist) Max and Fanny Steinthal, Charlottenburg, Berlin, by 1909, probably acquired in 1903 Thence by descent to the previous owner, Private Collection Belgium, 2012 Exhibited: Berlin, Köningliche Kunstakademie, Illustrierter Katalog der Ausstellung von Bildnissen des fünfzehnten bis achtzehnten Jahrhunderts aus dem Privatbesitz der Mitglieder des Vereins, 31 March – 30 April 1909, cat. -

Thesis, University of Amsterdam 2011 Cover Image: Detail of Willem Van Mieris, the Lute Player, 1711, Panel, 50 X 40.5 Cm, London, the Wallace Collection

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Imitation and innovation: Dutch genre painting 1680-1750 and its reception of the Golden Age Aono, J. Publication date 2011 Document Version Final published version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Aono, J. (2011). Imitation and innovation: Dutch genre painting 1680-1750 and its reception of the Golden Age. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:30 Sep 2021 Imitation and Innovation Dutch Genre Painting 1680-1750 and its Reception of the Golden Age Imitation and Innovation: Dutch Genre Painting 1680-1750 and its Reception of the Golden Age Ph.D. thesis, University of Amsterdam 2011 Cover image: detail of Willem van Mieris, The Lute Player, 1711, panel, 50 x 40.5 cm, London, The Wallace Collection. -

Willem Van Mieris

WILLEM VAN MIERIS (Leiden 1662 - Leiden 1747) The Penitent Mary Magdalene signed and indistinctly dated ‘W: Van Mieris fe 170[1?]’ (upper left) oil on panel 20.3 x 16.2 cm (8 x 6⅜ in) Provenance: Jacques de Roore (1686-1747); his sale, The Hague, 4 September 1747, no. 105 (fl. 153, together with no. 104, St. Jerome, as its pendant, to Van Spangen); John van Spangen, his sale, London, 12 February 1748, no. 74 (£20.9, together with no. 73, St. Jerome, as its pendant); Philippus van der Land; his sale, Amsterdam, 22 May 1776, no. 54 (for 180 florins, together with no. 55, St. Jerome, as its pendant); Caroline Anne, 4th Marchioness Ely, Eversly Park; her posthumous sale, Christie's, London, 3 August 1917, no. 46; with Cyril Andrade, London; Henry Blank (1872-1949), Newark, USA, by 1926,; his posthumous sale, Parke-Bernet, New York, 16 November 1949, lot 2; anonymous sale, Parke-Bernet, New York, 8 April 1950, lot 42; anonymous sale, Piasa, Paris, 13 June 1997; anonymous sale, Christie’s, London, 3 December 2008, lot 139; Private Collection, UK. Literature: Cornelis Hofstede de Groot, Beschreibendes und kritisches Verzeichnis der Werke der hervorragendsten Holländischen Maler des XVII Jahrhunderts, vol. X (Stuttgart/Paris, 1928), p. 116, no. 37 (with the incorrect dimensions). N THIS SMALL, EXQUISITely paINTED PICTURE, and passion for meticulously rendered detail, that characterised the work Willem van Mieris has depicted Mary Magdalene, grief-stricken of these masters. The foreground is a range of contrasting textures, such and living in the wilderness. After Christ’s crucifixion Mary was as the tough, battered leather of the book, against the cold stone ledge, believed to have become a hermit, devoting her life to penance and and these surfaces are rendered with the same painstaking care as the prayer. -

OLD MASTER PAINTINGS Wednesday 4 July 2018

OLD MASTER PAINTINGS Wednesday 4 July 2018 BONHAMS OLD MASTERS DEPARTMENT Andrew McKenzie Caroline Oliphant Lisa Greaves Director, Head of Department, Group Head of Pictures Department Director London London and Head of Sale London – – – Poppy Harvey-Jones Brian Koetser Bun Boisseau Junior Specialist Consultant Junior Cataloguer, London London London – – – Mark Fisher Madalina Lazen Director, European Paintings, Senior Specialist, European Paintings Los Angeles New York Bonhams 1793 Limited Bonhams International Board Bonhams UK Ltd Directors – – Registered No. 4326560 Robert Brooks Co-Chairman, Colin Sheaf Chairman, Gordon McFarlan, Andrew McKenzie, Registered Office: Montpelier Galleries Malcolm Barber Co-Chairman, Harvey Cammell Deputy Chairman, Simon Mitchell, Jeff Muse, Mike Neill, Montpelier Street, London SW7 1HH Colin Sheaf Deputy Chairman, Antony Bennett, Matthew Bradbury, Charlie O’Brien, Giles Peppiatt, India Phillips, Matthew Girling CEO, Lucinda Bredin, Simon Cottle, Andrew Currie, Peter Rees, John Sandon, Tim Schofield, +44 (0) 20 7393 3900 Patrick Meade Group Vice Chairman, Jean Ghika, Charles Graham-Campbell, Veronique Scorer, Robert Smith, James Stratton, +44 (0) 20 7393 3905 fax Jon Baddeley, Rupert Banner, Geoffrey Davies, Matthew Haley, Richard Harvey, Robin Hereford, Ralph Taylor, Charlie Thomas, David Williams, Jonathan Fairhurst, Asaph Hyman, James Knight, David Johnson, Charles Lanning, Grant MacDougall Michael Wynell-Mayow, Suzannah Yip. Caroline Oliphant, Shahin Virani, Edward Wilkinson, Leslie Wright. OLD MASTER -

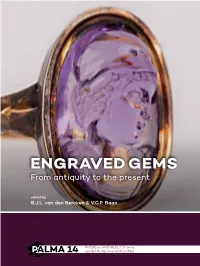

Engraved Gems

& Baan (eds) & Baan Bercken den Van ENGRAVED GEMS Many are no larger than a fingertip. They are engraved with symbols, magic spells and images of gods, animals and emperors. These stones were used for various purposes. The earliest ones served as seals for making impressions in soft materials. Later engraved gems were worn or carried as personal ornaments – usually rings, but sometimes talismans or amulets. The exquisite engraved designs were thought to imbue the gems with special powers. For example, the gods and rituals depicted on cylinder seals from Mesopotamia were thought to protect property and to lend force to agreements marked with the seals. This edited volume discusses some of the finest and most exceptional GEMS ENGRAVED precious and semi-precious stones from the collection of the Dutch National Museum of Antiquities – more than 5.800 engraved gems from the ancient Near East, Egypt, the classical world, renaissance and 17th- 20th centuries – and other special collections throughout Europe. Meet the people behind engraved gems: gem engravers, the people that used the gems, the people that re-used them and above all the gem collectors. This is the first major publication on engraved gems in the collection of the National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden since 1978. ENGRAVED GEMS From antiquity to the present edited by B.J.L. van den Bercken & V.C.P. Baan 14 ISBNSidestone 978-90-8890-505-6 Press Sidestone ISBN: 978-90-8890-505-6 PAPERS ON ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE LEIDEN MUSEUM OF ANTIQUITIES 9 789088 905056 PALMA 14 This is an Open Access publication. -

April 2007 Newsletter

historians of netherlandish art NEWSLETTER AND REVIEW OF BOOKS Dedicated to the Study of Netherlandish, German and Franco-Flemish Art and Architecture, 1350-1750 Vol. 24, No. 1 www.hnanews.org April 2007 Have a Drink at the Airport! Jan Pieter van Baurscheit (1669–1728), Fellow Drinkers, c. 1700. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. Exhibited Schiphol Airport, March 1–June 5, 2007 HNA Newsletter, Vol. 23, No. 2, November 2006 1 historians of netherlandish art 23 S. Adelaide Avenue, Highland Park NJ 08904 Telephone/Fax: (732) 937-8394 E-Mail: [email protected] www.hnanews.org Historians of Netherlandish Art Officers President - Wayne Franits Professor of Fine Arts Syracuse University Syracuse NY 13244-1200 Vice President - Stephanie Dickey Bader Chair in Northern Baroque Art Queen’s University Kingston ON K7L 3N6 Canada Treasurer - Leopoldine Prosperetti Johns Hopkins University North Charles Street Baltimore MD 21218 European Treasurer and Liaison - Fiona Healy Marc-Chagall-Str. 68 D-55127 Mainz Germany Board Members Contents Ann Jensen Adams Krista De Jonge HNA News .............................................................................. 1 Christine Göttler Personalia ................................................................................ 2 Julie Hochstrasser Exhibitions ............................................................................... 2 Alison Kettering Ron Spronk Museum News ......................................................................... 5 Marjorie E. Wieseman Scholarly Activities Conferences: To Attend .......................................................... -

![Prints, and Drawings in Leiden Outside of the Annual Fairs.[20] Number of Listings: 1600–1710](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2634/prints-and-drawings-in-leiden-outside-of-the-annual-fairs-20-number-of-listings-1600-1710-2902634.webp)

Prints, and Drawings in Leiden Outside of the Annual Fairs.[20] Number of Listings: 1600–1710

Leiden Fijnschilders and the Local Art Market in the Golden Age How to cite Bakker, Piet. “Leiden Fijnschilders and the Local Art Market in the Golden Age” (2017). In The Leiden Collection Catalogue, 3rd ed. Edited by Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. and Lara Yeager-Crasselt. New York, 2020–. https://theleidencollection.com/essays/updated-leiden-fijnschilders-and-the-local-art-market-in-the-golden-age/ (accessed October 02, 2021). A PDF of every version of this essay is available in this Online Catalogue's Archive, and the Archive is managed by a permanent URL. New versions are added only when a substantive change to the narrative occurs. © 2021 The Leiden Collection Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) Leiden Fijnschilders and the Local Art Market in the Golden Age Page 2 of 25 The year 1631 marked a turning point for painting in Leiden.[1] An abrupt end came to a period during which, sustained by a favorable economy, the number of painters had grown without interruption. This growth began in all of the cities in the Dutch Republic (fig 1) around 1610 and lasted until around mid-century in most of them. This was also true in Leiden, although it ground to a temporary halt in 1631 with the sudden departure of several painters, ushering in a period of artistic stagnation lasting close to a decade. By far the Fig 1. Graph: The Number of Painters in Six Cities in Holland: best-known painter to leave Leiden was Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–69) (fig 2 1590¬–1710. ), who moved to Amsterdam to run the workshop of the famous art dealer Hendrik Uylenburgh (ca. -

Daxer & M Arschall 20 19 XXVI

XXVI Daxer & Marschall 2019 Recent Acquisitions, Catalogue XXVI, 2019 Barer Strasse 44 | 80799 Munich | Germany Tel. +49 89 28 06 40 | Fax +49 89 28 17 57 | Mob. +49 172 890 86 40 [email protected] | www.daxermarschall.com 2 Oil Sketches, Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, 1668-1917 4 My special thanks go to Simone Brenner and Diek Groenewald for their research and their work on the texts. I am also grateful to them for so expertly supervising the production of the catalogue. We are much indebted to all those whose scholarship and expertise have helped in the preparation of this catalogue. In particular, our thanks go to: Peter Axer, Iris Berndt, Robert Bryce, Christine Buley-Uribe, Sue Cubitt, Kilian Heck, Wouter Kloek, Philipp Mansmann, Verena Marschall, Werner Murrer, Otto Naumann, Peter Prange, Dorothea Preys, Eddy Schavemaker, Annegret Schmidt- Philipps, Ines Schwarzer, Gerd Spitzer, Andreas Stolzenburg, Jörg Trempler, Jana Vedra, Vanessa Voigt, Wolf Zech. 6 Our latest catalogue Oil Sketches, Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, 2019 Unser diesjähriger Katalog Paintings, Oil Sketches, comes to you in good time for this year’s TEFAF, The European Fine Art Fair in Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, 2019 erreicht Sie Maastricht. TEFAF is the international art market high point of the year. It runs rechtzeitig vor dem wichtigsten Kunstmarktereignis from March 16-24, 2019. des Jahres, TEFAF, The European Fine Art Fair, Maastricht, 16. - 24. März 2019, auf der wir mit Stand The Golden Age of seventeenth-century Dutch painting is well represented in 332 vertreten sind. our 2019 catalogue, with particularly fine works by Jan van Mieris and Jan Steen. -

Download List of Works

Willem van Mieris, “Perseus & Andromeda” (detail, see cat. no. 35) GALERIE LOWET DE WOTRENGE Agents & Dealers in Fine Art Northern Works on Paper | 1550 to 1800 February 24 - March 25, 2018 Cover image: Cornelis Schut, “Apollo and Daphne” (detail; see cat no. 29) Gerrit Pietersz, “Phaeton asking Apollo for his chariot” (detail, see cat. no. 31) The current selection of works on paper - ranging from ‘première pensées’ and studies in pencil or ink to highly finished works of art in their own right - was gathered over a period of several years, culminating in this selling exhibition, opening at the gallery in the spring of 2018. In the course of these past years, a number of works on paper that would have made great additions to the current exhibition have found their way to various private and institutional clients. I thank all of them (you know who you are!) for putting their trust in my expertise. The works illustrated in this catalogue have now been gathered at our premises for the show, but I trust many of the sheets will also find their way into various collections across the globe soon. In that case, this catalogue will have to do as a humble memento of this particular moment in time. This selection of ‘northern’ works includes mostly works by Dutch and Flemish artists, with the occasional German thrown in. The division of artists into these geographical ‘schools’ should, however, always be taken with a grain of salt, as most of them were avid travellers - Flemish artists from the sixteenth century onwards viewed the obligatory trip to Italy almost as a pilgrimage - and were continuously being influenced by each other’s work.