Law and Disorder in the Postcolony

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Asian Journal of Dietetics Vol.2 No.3, 2020

ISSN2434-2688 Asian Journal of Dietetics Vol.2 No.3 2020 Contents Page Title and authors Special Topic 87 Professional Work and Rewards for Dietitians a History of Dietitians in Japan: No. 1 in a Series Teiji Nakamura Originals 89-96 School Lunch Program Could Control Snacking Habits and Decreased Energy and Lipid Intakes of 11-year-old Students in Jakarta Indri Kartiko Sari , Diah Mulyawati Utari, Sumiko Kamoshita, Shigeru Yamamoto 97-103 Vietnam’s New Food Culture with Textured Soybean Protein Can Save the Earth Ta Thi Ngoc, Ngo Thi Thu Hien, Nguyen Mai Phuong, Truong Thi Thu, Nguyen Huong Giang,Dinh Thi Dieu Hang, Nguyen Thuy Linh, Le Thi Huong, Nguyen Cong Khan, Shigeru Yamamoto 105-111 Factors in Low Prevalence of Child Obesity in Japan Sayako Aoki, Nobuko Sarukura,, Hitomi Takeichi,, Ayami Sano,, Noriko Horita, Yuko Hisatomi, Kenji Kugino, Saiko Shikanai 113-120 Nutritional Assessment Tools in Patients with Pulmonary Tuberculosis: A Cross- Sectional Study Badder Hina Afnan, Sahar Soomro, Saba Mughal, Syed Afnan Omer Ali, Madiha Patel, Nadeem Ahmed 121-127 Effects of Thinly Sliced Meat on Time, Number of Chews, and Food Intake in Elderly People with Tooth Loss Hien Ngo Thi Thu, Ngoc Ta Thi, Yen Ma Ngoc, Phuong Nguyen Mai, Thao Tran Phuong, Thu Truong Thi, Hang Dinh Thi Dieu, Linh Nguyen Thuy, Khan Nguyen Cong Yoshihiro Tanaka, Shigeru Yamamoto 129-134 Analysis of fiber intake and its sources in a year school lunches at a school in Japan Noriko Sumida, Saiko Shikanai, Nobuko Sarukura, Hitomi Takeich, Miho Nunokawa, Nguyen Mai Phuong, -

Proposed New 15Ml Reservoir and 1.2Km Pipeline, Lenasia South, Gauteng Province Draft

PROPOSED NEW 15ML RESERVOIR AND 1.2KM PIPELINE, LENASIA SOUTH, GAUTENG PROVINCE DRAFT PROPOSED NEW 15ML RESERVOIR AND 1.2KM PIPELINE, LENASIA SOUTH, GAUTENG PROVINCE ENVIRONMENTAL SCREENING REPORT DRAFT MAY 2014 Environmental, Social and OSH Consultants P.O. Box 1673 147 Bram Fischer Drive Tel: 011 781 1730 Sunninghill Ferndale Fax: 011 781 1731 2157 2194 Email: [email protected] Copyright Nemai Consulting 2014 MAY 2014 i PROPOSED NEW 15ML RESERVOIR AND 1.2KM PIPELINE, LENASIA SOUTH, GAUTENG PROVINCE DRAFT 1 TITLE AND APPROVAL PAGE Proposed new 15Ml reservoir and 1.2km pipeline, Lenasia South, PROJECT NAME: Gauteng Province. REPORT TITLE: Environmental Screening Report REPORT STATUS Draft AUTHORITY REF NO: N/A CLIENT: Johannesburg Water (011) 688 1669 (011) 11 688 1521 [email protected] P.O. Box 61542 Marshalltown 2107 PREPARED BY: Nemai Consulting C.C. (011) 781 1730 (011) 781 1731 [email protected] P.O. Box 1673 Sunnighill 2157 AUTHOR: Kristy Robertson REVIEWED BY: Sign Date APPROVED BY: Sign Date MAY 2014 ii PROPOSED NEW 15ML RESERVOIR AND 1.2KM PIPELINE, LENASIA SOUTH, GAUTENG PROVINCE DRAFT AMENDMENTS PAGE Date Nature of Amendment Amendment No. Signature 28/05/14 First Draft for Client Review 0 MAY 2014 iii PROPOSED NEW 15ML RESERVOIR AND 1.2KM PIPELINE, LENASIA SOUTH, GAUTENG PROVINCE DRAFT TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 TITLE AND APPROVAL PAGE 2 AMENDMENTS PAGE 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS 4 List of Figures 5 List of Tables 5 1 INTRODUCTION 7 2 SCOPE OF WORK 9 3 SITE LOCATION 10 4 BIOPHYSICAL FACTORS 11 4.1 Topography 11 4.2 Geology -

THE HORSEOWNER and STABLEMAN's COMPANION ; Or, Hints on the Selection, Purchase, and Management of the Horse

Morse lanacfement in Jsfealth and fyiseas George Jffrmatage, MK.C.VR mmm JOHNA.SEAVERNS — — — — STANDARD VETERINARY BOOKS. IMPORTANT TO FARMERS, BREEDERS, GRAZIERS, ETC. ETC. Price 21s. each. EVERY MAN HIS OWN HORSE DOCTOR. By George Armatage. M.R.C.V.S. In which is embodied Blaine's "Veterinary Art." Fourth Edition, Revised and consider- ably Enlarged. With upwards of 330 Original Illustrations, Coloured and Steel Plates, Anatomical Drawings, &c. In demy 8vo, half-bound, 884 pp. EVERY MAN HIS OWN CATTLE DOCTOR. By George Armatage, M.R.C.V.S. Sixth Edition. Forming a suitable Text-book for the Student and General Practitioner. With copious Notes, Additional Recipes, &c. , and upwards of 350 Practical Illustrations, showing Forms of Disease and Treat- ment, including Coloured Page Plates of the Foot and Mouth Disease. In demy 8vo, half-bound, 940 pp. THE SHEEP DOCTOR: A Guide to the British and Colonial Stockmaster in the Treatment and Prevention of Disease. By George Armatage, M.R.C.V.S. With Special Reference to Sheep Farming in the Colonies and other Sheep-producing Territories. With 150 Original Anatomical Illustrations. In demy 8vo, half-bound, price 15s. ; or, cloth gilt, 10s. 6d. UNIFORM WITH THIS VOLUME. Price 2s. 6d. each. CATTLE : Their Varieties and Management in Health and Disease. By George Armatage, M.R.C.V.S. With Illustrations. "Cheap, portable, neatly got up, and full of varied information, and contains useful facts as to habits, training, breeding, &c." Sporting Gazette. THE SHEEP: Its Varieties and Management in Health and Disease. By George Armatage, M.R.C.V.S. -

Pur-Sang (FRA) Mâle,Bai 1889 (XX=100.00%

ENERGIQUE (Pur-Sang (FRA) Mâle,Bai 1889 (XX=100.00% )) WHALEBONE PS 1807 SIR HERCULES PS 1826 BIRDCATCHER PERI PS 1822 PS 1833 OXFORD BOB BOOTY PS 1804 XX=100.00% - OX=0.00% GUICCIOLI PS 1823 FLIGHT V PS 1809 PS 1857 EMILIUS PS 1820 HONEY DEAR PLENIPOTENTIARY PS 1831 XX=100.00% - OX=0.00% HARRIETT PS 1819 PS 1844 © www.Webpedigrees.com STERLING BAY MIDDLETON PS 1833 XX=100.00% - OX=0.00% MY DEAR PS 1841 MISS LETTY PS 1834 PS 1868 CAMEL PS 1822 FLATCATCHER TOUCHSTONE PS 1831 XX=100.00% - OX=0.00% BANTER PS 1826 PS 1845 WHISPER FILHO DA PUTA PS 1812 XX=100.00% - OX=0.00% DECOY PS 1830 FINESSE PS 1815 PS 1857 HUMPHREY CLINKER PS 1822 SILENCE MELBOURNE PS 1834 XX=100.00% - OX=0.00% CERVANTES MARE PS 1825 PS 1848 ENERGY II MELBOURNE PS 1834 XX=100.00% - OX=0.00% SECRET PS 1853 MYSTERY PS 1842 PS 1880 BIRDCATCHER PS 1833 STOCKWELL THE BARON PS 1842 XX=100.00% - OX=0.00% ECHIDNA PS 1835 PS 1849 THE DUKE(THE DUKE OF GLENCOE PS 1831 XX=100.00% - OX=0.00% POCAHONTAS PS 1837 EDINBOURGH) MARPESSA PS 1830 TOUCHSTONE PS 1831 PS 1862 ORLANDO PS 1841 BAY CELIA VULTURE PS 1833 XX=100.00% - OX=0.00% PS 1851 CHERRY DUCHESS GLAUCUS PS 1830 XX=100.00% - OX=0.00% HERSEY PS 1842 HESTER PS 1832 PS 1871 WHALEBONE PS 1807 GEMMA DI VERGY SIR HERCULES PS 1826 XX=100.00% - OX=0.00% PERI PS 1822 PS 1854 MIRELLA HERON PS 1833 XX=100.00% - OX=0.00% SNOWDROP PS 1843 FAIRY PS 1823 PS 1863 MELBOURNE PS 1834 LADY RODEN WEST AUSTRALIAN PS 1850 XX=100.00% - OX=0.00% MOWERINA PS 1843 PS 1856 BAY MIDDLETON PS 1833 XX=100.00% - OX=0.00% ENNUI PS 1843 BLUE DEVILA PS 1837 PARTISAN -

In the Aquatic Ecosystems of Soweto/Lenasia

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in the aquatic ecosystems of Soweto/Lenasia Report to the WATER RESEARCH COMMISSION by Wihan Pheiffer1, Rialet Pieters1, Bettina Genthe2, Laura Quinn3, Henk Bouwman1 & Nico Smit1 1North-West University 2Council for Scientific and Industrial Research 3National Metrology Institute of South Africa WRC Report No. 2242/1/16 ISBN 978-1-4312-0801-2 June 2016 Obtainable from Water Research Commission Private Bag X03 Gezina, 0031 [email protected] or download from www.wrc.org.za DISCLAIMER This report has been reviewed by the Water Research Commission (WRC) and approved for publication. Approval does not signify that the contents necessarily reflect the views and policies of the WRC, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. © Water Research Commission ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY BACKGROUND Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) consist of fused benzene rings and the congeners have varying numbers of benzene rings, usually between two and six. They have a widespread distribution due to their formation by incomplete combustion of organic materials and are continuously released into the environment making them ever-present. The US EPA has earmarked 16 congeners that must be monitored and controlled because of their proven harmful effects on humans and wildlife. Anthropogenic activities largely increase the occurrence of these pollutants in the environment. A measurable amount of these PAHs are expected to find their way into aquatic ecosystems. RATIONALE In a previous study completed for the Water Research Commission (Project no K5/1561) on persistent organic pollutants in freshwater sites throughout the entire country, the PAHs had the highest levels of all of the organic pollutants analysed for. -

Table of Contents

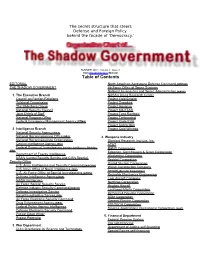

The secret structure that steers Defense and Foreign Policy behind the facade of 'Democracy.' SUMMER 2001 - Volume 1, Issue 3 from TrueDemocracy Website Table of Contents EDITORIAL North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) THE SHADOW GOVERNMENT Air Force Office of Space Systems National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) 1. The Executive Branch NASA's Ames Research Center Council on Foreign Relations Project Cold Empire Trilateral Commission Project Snowbird The Bilderberg Group Project Aquarius National Security Council Project MILSTAR Joint Chiefs of Staff Project Tacit Rainbow National Program Office Project Timberwind Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Project Code EVA Project Cobra Mist 2. Intelligence Branch Project Cold Witness National Security Agency (NSA) National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) 4. Weapons Industry National Reconnaissance Organization Stanford Research Institute, Inc. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) AT&T Federal Bureau of Investigation , Counter Intelligence Division RAND Corporation (FBI) Edgerton, Germhausen & Greer Corporation Department of Energy Intelligence Wackenhut Corporation NSA's Central Security Service and CIA's Special Bechtel Corporation Security Office United Nuclear Corporation U.S. Army Intelligence and Security Command (INSCOM) Walsh Construction Company U.S. Navy Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) Aerojet (Genstar Corporation) U.S. Air Force Office of Special Investigations (AFOSI) Reynolds Electronics Engineering Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) Lear Aircraft Company NASA Intelligence Northrop Corporation Air Force Special Security Service Hughes Aircraft Defense Industry Security Command (DISCO) Lockheed-Maritn Corporation Defense Investigative Service McDonnell-Douglas Corporation Naval Investigative Service (NIS) BDM Corporation Air Force Electronic Security Command General Electric Corporation Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) PSI-TECH Corporation Federal Police Agency Intelligence Science Applications International Corporation (SAIC) Defense Electronic Security Command Project Deep Water 5. -

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY of ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University Ofhong Kong

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY OF ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University ofHong Kong Asia today is one ofthe most dynamic regions ofthe world. The previously predominant image of 'timeless peasants' has given way to the image of fast-paced business people, mass consumerism and high-rise urban conglomerations. Yet much discourse remains entrenched in the polarities of 'East vs. West', 'Tradition vs. Change'. This series hopes to provide a forum for anthropological studies which break with such polarities. It will publish titles dealing with cosmopolitanism, cultural identity, representa tions, arts and performance. The complexities of urban Asia, its elites, its political rituals, and its families will also be explored. Dangerous Blood, Refined Souls Death Rituals among the Chinese in Singapore Tong Chee Kiong Folk Art Potters ofJapan Beyond an Anthropology of Aesthetics Brian Moeran Hong Kong The Anthropology of a Chinese Metropolis Edited by Grant Evans and Maria Tam Anthropology and Colonialism in Asia and Oceania Jan van Bremen and Akitoshi Shimizu Japanese Bosses, Chinese Workers Power and Control in a Hong Kong Megastore WOng Heung wah The Legend ofthe Golden Boat Regulation, Trade and Traders in the Borderlands of Laos, Thailand, China and Burma Andrew walker Cultural Crisis and Social Memory Politics of the Past in the Thai World Edited by Shigeharu Tanabe and Charles R Keyes The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I PRESS HONOLULU Editorial Matter © 2002 David Y. -

Rafael Marcelo Viegas

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO DE JANEIRO FACULDADE DE LETRAS Rafael Marcelo Viegas “Dando peso à fumaça” Mundos paralelos das crenças absurdas em Dos Coxos (Ensaios III, XI) Texto apresentado ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Letras Neolatinas, Faculdade de Letras, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, como parte dos requisitos necessários à defesa de Doutorado em Letras Neolatinas, Literatura Francesa. Orientador: Prof. Marcelo Jacques de Moraes Co-Orientador: Prof. João Camillo Barros de Oliveira Penna Rio de Janeiro 2014 CATALOGAÇÃO NA FONTE UFRJ/SIBI/ V656 Viegas, Rafael Marcelo. “Dando peso à fumaça”. Mundos paralelos das crenças absurdas em Dos Coxos (Ensaios III, XI) / Rafael Marcelo Viegas. – 2014. 282f. Orientador: Marcelo Jacques de Moraes. Co-orientador: João Camilo Barros de Oliveira Penna Tese (doutorado) – Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Faculdade de Letras. Montaigne, Michel de, 1533-1592 – Teses. 2. Ensaio – Teses. 3. Narrativa – Teses. 4. Literatura – História e crítica – Teoria, etc – Teses. I. Moraes, Marcelo Jacques de Moraes. II. Penna, João Camillo Barros de Oliveira Penna. III. Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro. Faculdade de Letras. IV. Título. CDD 809 Título em inglês: “Able to give weight to smoke”: Parallel Worlds of bizarre beliefs (Essays III, XI). UFRJ – Faculdade de Letras | Rio de Janeiro | 2014 FOLHA DE APROVAÇÃO Rafael Marcelo Viegas. “Dando peso à fumaça”. Mundos paralelos das crenças absurdas em Dos Coxos (Ensaios III, XI) Rio de Janeiro, 28 de janeiro de 2014 __________________________________________ -

The Making and Unmaking of Ethnic Boundaries: a Multilevel Process Theory1

The Making and Unmaking of Ethnic Boundaries: A Multilevel Process Theory1 Andreas Wimmer University of California, Los Angeles Primordialist and constructivist authors have debated the nature of ethnicity “as such” and therefore failed to explain why its charac- teristics vary so dramatically across cases, displaying different de- grees of social closure, political salience, cultural distinctiveness, and historical stability. The author introduces a multilevel process theory to understand how these characteristics are generated and trans- formed over time. The theory assumes that ethnic boundaries are the outcome of the classificatory struggles and negotiations between actors situated in a social field. Three characteristics of a field—the institutional order, distribution of power, and political networks— determine which actors will adopt which strategy of ethnic boundary making. The author then discusses the conditions under which these negotiations will lead to a shared understanding of the location and meaning of boundaries. The nature of this consensus explains the particular characteristics of an ethnic boundary. A final section iden- tifies endogenous and exogenous mechanisms of change. TOWARD A COMPARATIVE SOCIOLOGY OF ETHNIC BOUNDARIES Beyond Constructivism The comparative study of ethnicity rests firmly on the ground established by Fredrik Barth (1969b) in his well-known introduction to a collection 1 Various versions of this article were presented at UCLA’s Department of Sociology, the Institute for Migration Research and Intercultural Studies of the University of Osnabru¨ ck, Harvard’s Center for European Studies, the Center for Comparative Re- search of Yale University, the Association for the Study of Ethnicity at the London School of Economics, the Center for Ethnicity and Citizenship of the University of Bristol, the Department of Political Science and International Relations of University College Dublin, and the Department of Sociology of the University of Go¨ttingen. -

NP 2013.Docx

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 15/04/13 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : F Avant 1996, des chevaux qui ont une renommée F Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally internationale, soit comme principaux renowned, either as main stallions and reproducteurs ou comme champions en courses broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or (en plat et en obstacles), jump) F de 1996 à 2004, des gagnants des neuf grandes F from 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F à partir de 2005, des gagnants des onze grandes F since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (à partir de 2006 / from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F des principaux reproducteurs, inscrits à la F the main stallions and broodmares, registered demande du Comité International des Stud on request of the International Stud Book Books. -

Tsukuba Innovation Plaza Tsukuba Center Bld. Square

May 12th (Sat) 12:00pm - 6:00pm, 13th (Sun) 10:00am - 5:00pm Tsukuba Center Bld. Square Tsukuba City Society of Commerce and Industry International Exchange Fair No. Shop Contents No. Shop Contents No. Group/Country Contents No. Group/Country Contents Meat (pork or beef) on Introduction of French Fried chicken, yakitori, ESPACE・TSUKUBA- 1 Ichinoya 20 Yoshimura Meat skewers grilled over 26 culture with books & 44 Papa chef 【Turkey】 Kebabs, long potato FRANCE 【France】 fried noodles, mixed rice charcoal posters Sanzokuyaki Mongolian cuisine(dishes with Inamura Cold Sweets Group Jamm SENEGAL Senegalese cuisine (mafe, Mongolian traditional 2 Shaved ice, dish ice 21 Tsukuba Ham (Grilled food) 27 45 meat, wheat flour, onion, garlic, and 【Senegal】 Senegalese chicken, fataia) food 【Mongolia】 Shop yogurt drink oil) African Home Cuisine Hyakkotei , Tsukuba Fried rice, fried noodles, spring Take-out Shop, Kenya cuisine Champs de ble French local specialties (galette, cr rolls, dandan noodles, fried SHIDAMO 3 22 Fried Tsukuba chicken 28 46 êpe, cidre, wine, soft drink) University chicken, shrimp with mayonnaise Rakuen 【Kenya】 (pilaf, samosa,mandazi) 【France】 Indian curry, tandoori Asian Kitchen Sri Lanka cuisine Fried-soup-dumplings, Taiwan B-grade gourmet Indian Curry Japan-China friendship shou zhua bing (chinese pancakes), fried stick 4 chicken, samosa, draft Shouette Garlic sauteed pork bowl 29 AMMA CURRY (cotton candy, choco 47 GUNS organizations 【China】 gyoza (dumpling), sesami balls, Taiwan lu rou fan beer, lassi 【Sri Lanka】 banana) (braised -

Private Testing Centres

CORONAVIRUS PRIVATE TESTING CENTRES The following centres are designated testing facilities for COVID-19: Gauteng Kwa-Zulu Natal Limpopo ALBERTON LADYSMITH POLOKWANE Alberton IPS, 68 Voortrekker Road, New Lenmed La Verna Private Hospital, 1 Convent 44A Grobler street, Polokwane Central Redruth, Alberton Road, Ladysmith TZANEEN MULBARTON NEWCASTLE 71 Wolksberg Road, Ivory Tusk Lodge Netcare, Room 206, Mulbarton Medical Centre, Mediclinic Newcastle Private Hospital, 78 Bird THOUYANDOU 27 True North Road Street, Newcastle Central, Newcastle Corner Mpehephu and Mvusuludzo near Cash VEREENIGING EMPANGENI build 46 Rhodes Avenue, Vereeniging Life Empangeni Garden Clinic, 50 Biyela Street, PHALABORWA Empangeni Central LENASIA Clinix Private Hospital, No 86 Grosvenor Street Lenmed Hospitall, Lenesia South UMHLANGA DAXINA Busamed Gateway Private Hospital, 36-38 Aurora Dr, Umhlanga Rocks, Umhlanga Daxina Medical Centre Western Cape BEREA KRUGERSDORP 1st Floor, Mayet Medical Centre, 482 Randles Krugersdorp Lab, Outpatient Depot, 1 Boshoff BELLVILLE Road, Sydenham, Berea Street, Krugersdorp 2 Heide Street, Bloemhof, Cape Town DURBAN SOWETO BRACKENFELL Ahmed Al-Khadi private Hospital, 490 Jan Smuts Soweto Healthcare Hub Brackenfell Medical Centre, Cnr Brackenfell and Hwy, Mayville, Durban BIRCHLEIGH Old Paarl Road, Cape Town CHATSWORTH Birchleigh Depot, 7 Leo Street CAPE TOWN Life Chatsmed Private Hospital, Suite 121-201, Cnr Longmarket and Parliament Street, Cape KEMPTON PARK West Wing Chatsmed Garden Hospital, 80 Town Kempton Square Shopping Centre,