ADMINISTRATIVE NOTES Newsletter of the Federal Depository Library Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From the American Dream to … Bailout America: How the Government

From the American dream to … bailout America: How the government loosened credit standards and led to the mortgage meltdown Compiled by Edward Pinto, American Enterprise Institute In the early 1990s, Fannie Mae‘s CEO Jim Johnson developed a plan to protect Fannie‘s lucrative charter privileges bestowed by Congress. Ply Congress with copious amounts of affordable housing and Fannie‘s privileges would be secure. It required ―transforming the housing finance system‖ by drastically loosening of loan underwriting standards. Fannie garnered support from community advocacy groups like ACORN and members of Congress. In 1995 President Clinton formalized Fannie‘s plan into the National Homeownership Strategy. President Clinton stated it ―will not cost the taxpayers one extra cent.‖ From 1992 onward, ―skin in the game‖ was progressively eliminated from housing finance. And it worked – Fannie‘s supporters in and outside Congress successfully protected Fannie‘s (and Freddie‘s) charter privileges against all comers – until the American Dream became Bailout America. TIMELINE Credit loosening Warning 1991 HUD Commission complains ―Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac‘s underwriting standards are oriented towards ‗plain vanilla‘ mortgage‖ [Read More] 1991 Lenders will respond to the most conservative standards unless [Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac] are aggressive and convincing in their efforts to expand historically narrow underwriting [Read More] 1992 Countrywide and Fannie Mae join forces to originate ―flexibly underwritten loans‖ [Read More] 1992 Congress passes -

The Role of Government Affordable Housing Policy in Creating the Global Financial Crisis of 2008 STAFF REPORT U.S

U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Oversight and Government Reform Darrell Issa (CA-49), Ranking Member The Role of Government Affordable Housing Policy in Creating the Global Financial Crisis of 2008 STAFF REPORT U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 111TH CONGRESS COMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND GOVERNMENT REFORM ORIGINALLY RELEASED JULY 1, 2009 * UPDATED MAY 12, 2010 INTRODUCTION The housing bubble that burst in 2007 and led to a financial crisis can be traced back to federal government intervention in the U.S. housing market intended to help provide homeownership opportunities for more Americans. This intervention began with two government-backed corporations, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which privatized their profits but socialized their risks, creating powerful incentives for them to act recklessly and exposing taxpayers to tremendous losses. Government intervention also created “affordable” but dangerous lending policies which encouraged lower down payments, looser underwriting standards and higher leverage. Finally, government intervention created a nexus of vested interests – politicians, lenders and lobbyists – who profited from the “affordable” housing market and acted to kill reforms. In the short run, this government intervention was successful in its stated goal – raising the national homeownership rate. However, the ultimate effect was to create a mortgage tsunami that wrought devastation on the American people and economy. While government intervention was not the sole cause of the financial crisis, its role was significant and has received too little attention. In recent months it has been impossible to watch a television news program without seeing a Member of Congress or an Administration official put forward a new recovery proposal or engage in the public flogging of a financial company official whose poor decisions, and perhaps greed, resulted in huge losses and great suffering. -

Contractor Reports: Executive Summaries and Bibliographies

65 APPENDIX E: CONTRACTOR REPORTS: EXECUTIVE SUMMARIES AND BIBLIOGRAPHIES RAND SETTING PRIORITIES AND COORDINATING FEDERAL R&D ACROSS FIELDS OF SCIENCE: A LITERATURE REVIEW SRI INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM ON INTERNATIONAL MODELS OF BUDGET COORDINATION AND PRIORITY SETTING FOR S&T These reports were prepared as background for the study undertaken for the National Science Board by the NSB Ad Hoc Committee on Strategic Science and Engineering Policy Issues. The contents of these reports are the responsibility of the respective contractors and do not neces- sarily reflect the views of the Committee or the National Science Board. FEDERAL RESEARCH RESOURCES: 66 A PROCESS FOR SETTING PRIORITIES RAND SETTING PRIORITIES AND COORDINATING FEDERAL R&D ACROSS FIELDS OF SCIENCE: A LITERATURE REVIEW Steven W. Popper, Caroline S. Wagner, Donna L. Fossum, William S. Stiles DRU-2286-NSF April 2000 Prepared for the National Science Board Science and Technology Policy Institute The RAND unrestricted draft series is intended to transmit preliminary results of RAND research. Unrestricted drafts have not been formally reviewed or edited. The views and conclusions expressed are tentative. A draft should not be cited or quoted without permission of the author, unless the preface grants such permission. RAND IS A NONPROFIT INSTITUTION THAT HELPS IMPROVE PUBLIC POLICY THROUGH RESEARCH AND ANALYSIS. RAND’S PUBLICATIONS AND DRAFTS DO NOT NECESSARILY REFLECT THE OPINIONS OR POLICIES OF ITS RESEARCH SPONSORS. SETTING PRIORITIES AND COORDINATING FEDERAL R&D ACROSS FIELDS OF SCIENCE: A LITERATURE REVIEW 67 APPENDIXRAND E (CONTINUED) PREFACE The National Science Board is presently exploring how the U.S. federal government sets priorities in research and development and whether changes are needed in the decision-making process. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—HOUSE October 28

H9586 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD Ð HOUSE October 28, 1997 Mr. Speaker, first, this is a very potential threat to philanthropic inter- The Depot Caucus believes this work straightforward rule, one hour of de- ests, it would be difficult for the Pre- should go to the depots, regardless of bate on the conference report. I have sidio Trust to meet its self-sufficiency cost and regardless of what the Defense no problem with the rule. Secondly, I requirements without a timely and Department needs. They are protecting would like to say to my distinguished thorough cleanup of the Presidio. Se- their home turf, and I respect that, but colleague, the gentleman from Ohio curing the leases necessary to generate it is also bad policy, and this is not [Mr. KASICH] that there is a different revenues is essential to the success of what we should be supporting. It puts perspective and point of view on the trust, and can only be accom- our troops at a disadvantage. Bosnia. This obviously is not the time plished if the cleanup is timely and The Secretary of Defense and his nor the place for us to engage in sub- thorough. military commanders need the flexibil- stantive debate on that matter. I would like to yield to the gen- ity on the current law to modernize. To With the balance of the time, Mr. tleman from Colorado for his final re- do so, they need to have the ability to Speaker, I would like to, for the pur- marks. take the best and most appropriate poses of colloquy, engage the distin- Mr. -

The Dc Revitalization

APPENDIX ONE: THE D.C. REVITALIZATION ACT: HISTORY, PROVISIONS AND PROMISES Photo by Michael Bonfigli 22614 DC Appleseed Report-PC.indd 80 12/4/08 6:56:31 PM Jon Bouker, Arent Fox LLP residents, representing 22,000 households, left between 1990 and 1995. This flight contributed to the erosion of the District’s tax base and exacerbated budget shortfalls.171 It was a vicious cycle that was driving the city toward insolvency. The growing economic crisis would soon come to the attention of the Clinton Administration and the newly elected Republican Congress. Despite their myriad differences on the wide range of national When Congress granted home rule to the issues facing the country, the President District of Columbia in 1973,167 Rep. Charles and the Congress would have to come C. Diggs, Jr., then chair of the House D.C. together to prevent the Nation’s Capital Committee, declared that Washington’s from sliding into bankruptcy. Their analysis residents had become “masters of their ultimately would examine both sides of the own fate.”168 Led by a democratically city’s balance sheet: the federally imposed elected mayor and city-council, the District limitations on revenue and the District’s own was not quite its own “master” but a semi- expenditures. autonomous, unique, government entity with city and state functions and limited Because tackling the District’s revenue power over its own budget and laws.169 limitations presented far too many political However, a mere two decades later, the challenges for the Congress and the District’s limited home rule was in crisis. -

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac Get Away with It for So Long?." Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac: Turning the American Dream Into a Nightmare

McDonald, Oonagh. "Why Did Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac Get Away with It for So Long?." Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac: Turning the American Dream into a Nightmare. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2012. 266–282. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 26 Sep. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781780930039.ch-012>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 26 September 2021, 14:30 UTC. Copyright © Oonagh McDonald 2012. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 12 Why Did Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac Get Away with It for So Long? A weak regulator Limits of its authority Quite simply, there were two reasons for this: the “weakness” of the regulator (the Offi ce of Housing and Enterprise Oversight, or OFHEO), and the lobbying conducted by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. The fi rst reason makes it look as though OFHEO was simply asleep on the job or in the grip of the Enterprises, but a brief examination of the powers and resources available to the regulator will show that things were not quite that simple. OFHEO was established as part of the Act which gave Fannie and Freddie their Charters in 1992.1 It was the GSEs’ “safety and soundness regulator” and an independent agency within the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) until it was abolished in 2008. HUD was the “mission” regulator of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, charged with ensuring that the Enterprises enhanced the availability of mortgage credit by creating and maintaining a secondary market for residential mortgages. -

Directory of Federal Financial Managers

I I ne of the objectives of the Joint Financial Management Im rovement Program (JFMIP) is to encourage and *“I’ promote the sharing and exchan e, throughout the federa Pgovernment, of information concernin good financial -0 techniques and practices. Actor B ingly, the JFMIP annually issues the Directory of Federal Financia f Managers to improve communications among federal financial managers, promote an improved climate for financial management, and facilitate sharing of experience and knowledge among financial managers. In order to provide timely and responsive service to the financial management community, the JFMIP asks to be informed of any changes of content. Please contact the JFMIP in writing at the address below: Joint Financial Management Improvement Program Room 3111 441 C Street NW Washington, DC 20548-0001 Any comments, su estions or questions concerning the Directory or any other JFMIP publications should be sent to the above address or faxe 7 to JFMIP ,fax (202) 512-9593. ,, .’ _’ ,I” ., ‘, ,,. “’ ; 9’ :, ! Table of Contents .. : : ’ i s ',,,; ,;,;,1 'i ,’ ,. ,, :. >./ ..I ; ', ,a 1': i Organizational Listing:, Administrative Dffice of the U.S. Courts - - - - - - - - - - - - 1 Labor, Department of, : -----------------,r,---,37 African Development’Foundation - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 1 LegalServices Corporation ------------------3g Agency for International Development- - - - - - - - - - - - - 1 Library of Congress_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ ‘$9 Agriculture; Depafimentof- L _ I’- _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ -

Appendix C—Checklist of White House Press Releases

Appendix CÐChecklist of White House Press Releases The following list contains releases of the Office of Released January 13 the Press Secretary which are not included in this Transcript of a press briefing by Press Secretary Mike book. McCurry Released January 5 Statement by the Press Secretary: Official Visit by Transcript of a press briefing by Press Secretary Mike British Prime Minister Tony Blair McCurry Released January 14 Transcript of a press briefing by Office of Manage- Transcript of a press briefing by Press Secretary Mike ment and Budget Director Franklin Raines and Na- McCurry tional Economic Council Director Gene Sperling on the budget Statement by the Press Secretary on the President's confidence in Secretary of Labor Alexis Herman Statement by the Press Secretary: Visit by President Stoyanov of Bulgaria Statement by Counsel to the President Charles F.C. Ruff on Independent Counsel Kenneth Starr's inter- Released January 6 view of the First Lady Transcript of a press briefing by Press Secretary Mike McCurry Released January 15 Transcript of a press briefing by Health and Human Statement by the Press Secretary on the Presidential Services Secretary Donna Shalala, Labor Secretary Medal of Freedom recipients Alexis Herman, and National Economic Council Di- Statement by the Press Secretary: Agreement between rector Gene Sperling on proposed legislation on Medi- Indonesia and the IMF care Statement by the Press Secretary: China Nuclear Cer- Released January 7 tification Transcript of a press briefing by Press Secretary Mike -

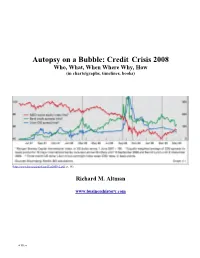

Autopsy on a Bubble: Credit Crisis 2008 Who, What, When Where Why, How (In Charts/Graphs, Timelines, Books)

Autopsy on a Bubble: Credit Crisis 2008 Who, What, When Where Why, How (in charts/graphs, timelines, books) (http://www.bis.org/publ/arpdf/ar2009e2.pdf, p, 16) Richard M. Altman www.businesshistory.com «URLs» Credit Crisis and the Stock Market D I K P P Data - Becomes Information When Interpreted Information - Becomes Knowledge When Understood Knowledge - Becomes Power When Used Power - Becomes Progress When Measured Progress - Becomes Data When Analyzed «URLs» Credit Crisis and Capitalism (http://www.scribd.com/doc/37263162/0061788406, p. 92) «URLs» Credit Crisis and Capitalism (http://www.scribd.com/doc/37263162/0061788406, p. 93) «URLs» Table of Contents 1. Introduction p. 6 a) Cash and Risk p. 6 b) History’s Bubbles p. 7 c) Four Phases of a Bubble p. 8 d) Key Dates p. 12 2. What Happened: Four Stages - Cash, Risk (2) and Rescue p. 13 a) Historical Perspective p. 14 b) Stage 1: 2000-2003 - Cash Grew p. 26 c) Stage 2: 2003-2007 - Credit Risk p. 44 d) Stage 3: 2007-2009 - Market Risk (Event Risk) p. 69 e) Stage 4: 2009-2010 - Rescue: Liquidity and Solvency p. 95 3. People: Who Was Involved p. 115 4. Government/Corporate: When, What, Where (Descriptive) p. 125 a) Government Timeline p. 126 b) Corporate Timeline p. 141 5. Books: Why, How (Interpretive): p. 156 a) Credit Crisis Books (Year, Author) p. 157 b) Credit Crisis: Related Books (Author) p. 180 c) Credit Crisis: Films - (Year, Director) p. 188 d) Wall Street Books (Firm, Year, Author) p. 189 e) Wall Street: Related Books (Author) p. -

Crony Capitalism,” the Cozy Relationship Between Government Officials and Corporate Execs That Encouraged Bad Investment Decisions

U.S. officials piously THE MAGAZINE OF INTERNATIONAL ECONOMIC POLICY 888 16th Street, N.W., Suite 740 lecture the world. Washington, D.C. 20006 Phone: 202-861-0791 • Fax: 202-861-0790 www.international-economy.com But what about Fannie Mae and the other cozy arrangements right Crony under their noses? Capitalism: American n the wake of the financial crisis that spread through Asia in 1997 and 1998, Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin and his deputy, Lawrence Summers, pinned the region’s Style problems in part on a pervasive business cul- ture commonly known as “crony capitalism,” the cozy relationship between government officials and corporate execs that encouraged bad investment decisions. In a January 1998 speech, Ru- B Y O WEN U LLMANN Ibin, who resigned this summer, cited “close links be- tween governments, banks and corporations [that] led to fundamentally unsound investments.” And in March 1998, Summers, Rubin’s successor as secretary, fault- ed a system that relied on “relationship-driven finance not capital markets.” The criticism is right on point. Yet in Washington, D.C., a form of crony capitalism exists right under Treasury’s nose — and with its bless- ing. It is called a government-sponsored enterprise (GSE), a private corporation that receives special bene- fits under a charter granted by the federal government. The relationship is worth billions to the GSEs and their shareholders. The rewards have been great, as well, for the executives who run the companies, and government Owen Ullmann, a former senior writer at Business Week, covers economic policy and politics for USA Today. -

Is Neutral the New Black?: Advancing Black Interests Under the First Black Presidents

IS NEUTRAL THE NEW BLACK?: ADVANCING BLACK INTERESTS UNDER THE FIRST BLACK PRESIDENTS An undergraduate thesis presented by SAMANTHA JOY FAY Submitted to the Department of Political Science of Haverford College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF ARTS IN POLITICAL SCIENCE Advised by Professor Stephen J. McGovern April 2014 Copyright © 2014 Samantha Joy Fay All Rights Reserved 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, I am eternally grateful to God for giving me the strength to get through this process, especially when I did not think I had it in me to keep going. If nothing else, writing this has affirmed for me that through Him all things are possible. To God be the glory. Second, thank you to everyone who contributed to my research, especially my advisor. It would take far too long for me to name all of you, and I would hate to forget someone, so I hope it will suffice to say that I am indebted to you for the time and effort you expended on my behalf. Third, I have to give a shout-out to my friends. I have neglected you in the worst way this year, but I am so grateful for the distractions from the misery of work, your attempts to stay up as late as I do (nice try), and most of all your understanding. I really do appreciate you, your encouraging words, your shared cynicism, and your hugs. I hope this makes up for me not being able to show it as much as I wanted to this year. -

Less Access to Less Information by and About the U.S. Government Xxix: A

ALA Washington Office Chronology INFORMATION ACCESS American Library Association, Washington Office 1301 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW, Suite 403 Wasliington, D.C. 20004 -1701 Tel: 202-628-8410 Fax:202-628-8419 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.ala.org/washoff December 1997 Less Access to Less Information By and About THE U.S. Government: XXIX A 1997 Chronology: June - December Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 http://www.archive.org/cletails/lessaccesstoless29amer Less Access to Less Information By and About THE U.S. Government: XXIX A 1997 Chronology: June - December contents Introduction 4 NOVEMBER Compromise reached on sampling for the 2000 JUNE census 12 Federal agencies disagree about evidence regarding National Academy of Sciences exempted from veterans' illnesses 5 open access law 12 House Committee criticizes U.S. intelligence Plan revealed to blame Castro if Glenn mission agencies 5 failed 12 Research needed before government databases can National Archives destroys Naval Research be easily accessible to public 5 Laboratory' historical records 12 Army charged with destroying sex survey data 6 More troops were exposed to chemicals in area of DECEMBER Iraqi dump 6 Tape transcripts reveal Nixon White House media ALA joins in suit to preserve electronic federal strategy 13 records 6 U.S. role in melting Nazi gold revealed in long-secret Right-to-knovv week celebrated 7 documents 13 U.S. argues that cutting would jeopardize Nixon JULY tapes 14 Freedom of Information Act implemented U.S. sued for violating Freedom of Information