Collective Behaviour Without Collective Order in Wild Swarms of Midges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diptera: Corethrellidae) Author(S): Priyanka De Silva and Ximena E

First Report of the Mating Behavior of a Species of Frog-Biting Midge (Diptera: Corethrellidae) Author(s): Priyanka De Silva and Ximena E. Bernal Source: Florida Entomologist, 96(4):1522-1529. 2013. Published By: Florida Entomological Society DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1653/024.096.0434 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.1653/024.096.0434 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/ terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. 1522 Florida Entomologist 96(4) December 2013 FIRST REPORT OF THE MATING BEHAVIOR OF A SPECIES OF FROG-BITING MIDGE (DIPTERA: CORETHRELLIDAE) PRIYANKA DE SILVA1,* AND XIMENA E. BERNAL1, 2 1Department of Biological Science, Texas Tech University, P.O. Box 43131, Lubbock, TX, 79409, USA 2Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Apartado 2072, Balboa, Republic of Panama *Corresponding author; E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Swarming is a common mating behavior present throughout Diptera and, in particular, in species of lower flies (Nematocerous Diptera). -

DNA Barcoding

Full-time PhD studies of Ecology and Environmental Protection Piotr Gadawski Species diversity and origin of non-biting midges (Chironomidae) from a geologically young lake PhD Thesis and its old spring system Performed in Department of Invertebrate Zoology and Hydrobiology in Institute of Ecology and Environmental Protection Różnorodność gatunkowa i pochodzenie fauny Supervisor: ochotkowatych (Chironomidae) z geologicznie Prof. dr hab. Michał Grabowski młodego jeziora i starego systemu źródlisk Auxiliary supervisor: Dr. Matteo Montagna, Assoc. Prof. Łódź, 2020 Łódź, 2020 Table of contents Acknowledgements ..........................................................................................................3 Summary ...........................................................................................................................4 General introduction .........................................................................................................6 Skadar Lake ...................................................................................................................7 Chironomidae ..............................................................................................................10 Species concept and integrative taxonomy .................................................................12 DNA barcoding ...........................................................................................................14 Chapter I. First insight into the diversity and ecology of non-biting midges (Diptera: Chironomidae) -

Phenology of Non-Biting Midges (Diptera: Chironomidae) in Peatland Ponds, Central Poland

© Entomologica Fennica. 1 June 2018 Phenology of non-biting midges (Diptera: Chironomidae) in peatland ponds, Central Poland Mateusz P³óciennik, Martyna Skonieczka, Olga Antczak & Jacek Siciñski P³óciennik, M., Skonieczka, M., Antczak, O. & Siciñski, J. 2018: Phenology of non-biting midges (Diptera: Chironomidae) in peatland ponds, Central Poland. Entomol. Fennica 29: 6174. Non-biting midges are one ofthe most diverse and abundant aquatic insects in peatlands. The R¹bieñ mire is a raised bog located on the edge ofthe Lodz Ag - glomeration in Central Poland. After peat extraction, many ponds remained in the R¹bieñ area. During the growing season in 2012, adult chironomids were col- lected by a light trap and a hand net near one ofthe excavation ponds. The pheno - logy of adult flight period was documented from April to November. Thirty-one species were recorded and assigned to one offivephenology groups. Three pa- rameters reflecting duration of daytime and weather conditions, i.e. air tempera- ture, air humidity, were found to covary significantly with the observed flight pe- riods. Taxa emerging in the spring may be classified as cold-adapted and those collected in the summer only as preferring higher air temperature. Emergence in late summer was related to a shorter duration ofdaytime. M. P³óciennik, O. Antczak & J. Siciñski, Department of Invertebrate Zoology and Hydrobiology, University of Lodz, 12/16 Banacha St., Lodz 90-237, Poland; E- mails: [email protected], [email protected], sicinski@bio- l.uni.lodz.pl M. Skonieczka, 22/61 Pi³sudskiego St., Aleksandrów £ódzki, 95-070, Poland; e- mail: [email protected] Received 21 December 2016, accepted 27 September 2017 1. -

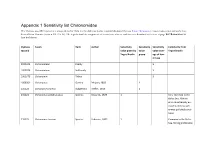

Appendix 1 Sensitivity List Chironomidae the Dyntaxa Taxonid Represents a Unique Identifier from the Swedish Taxonomic Standard Database Dyntaxa (

Appendix 1 Sensitivity list Chironomidae The Dyntaxa taxonID represents a unique identifier from the Swedish taxonomic standard database Dyntaxa (http://dyntaxa.se). Taxon names rank and author are derived from Dyntaxa (version 2013-06-26). The logic behind the assignment of a sensitivity class to each taxon is described in the text at page Fel! Bokmärket är inte definierat.. Dyntaxa Taxon Rank Author Sensitivity Sensitivity Sensitivity Comments from taxonid value given by value value aver- Yngve Brodin Yngve Brodin group age of low- er taxa 2001302 Chironomidae Family 5 1009974 Chironominae Subfamily 5 1009975 Chironomini Tribus 5 1009301 Chironomus Genera Meigen, 1803 1 235223 Camptochironomus Subgenera Kieffer, 1918 1 235224 Chironomus pallidivittatus Species Edwards, 1929 1 Very common in the Baltic Sea. Able to endure extremely eu- trophic and also oth- erwise polluted condi- tions. 235225 Chironomus tentans Species Fabricius, 1805 1 Common in the Baltic Sea. Strong preference WATERS: A PROBABILITY BASED INDEX FOR BENTHIC ASSESSMENT IN THE BALTIC SEA Dyntaxa Taxon Rank Author Sensitivity Sensitivity Sensitivity Comments from taxonid value given by value value aver- Yngve Brodin Yngve Brodin group age of low- er taxa for eutrophic and even extremely eutrophic and polluted condi- tions. 235228 Chironomus Subgenera Meigen, 1803 1 235234 Chironomus annularius Species Meigen, 1818 1 Rather common in the Baltic Sea, easily con- fused with several other Chironomus species bout as larvae and adults. 235235 Chironomus anthracinus Species Zetterstedt, 1860 1 Common north of Åland, otherwise less common in the Baltic Sea. Mainly found below the littoral. Prefers less strongly 2 WATERS: A PROBABILITY BASED INDEX FOR BENTHIC ASSESSMENT IN THE BALTIC SEA Dyntaxa Taxon Rank Author Sensitivity Sensitivity Sensitivity Comments from taxonid value given by value value aver- Yngve Brodin Yngve Brodin group age of low- er taxa eutrophic conditions than C. -

FEEDING BEHAVIOUR OF'breeding WIGEON Anas Penelope in RELATION to SEASONAL EMERGENCE and SWARMING BEHAVIOUR of CHIRONOMIDS

409 FEEDING BEHAVIOUR OF'BREEDING WIGEON Anas penelope IN RELATION TO SEASONAL EMERGENCE AND SWARMING BEHAVIOUR OF CHIRONOMIDS ODD W. JACOBSEN ABSTRACT Emergence ofchironomids started in mid-April, and reached a peak at the end of April and in the beginning of May. Most "spring" chiro nomids emerged around noon, whereas the majority of chironomids emerg ing later in the season, appeared at night. In general, there was a positive correlation between the seasonal emergencl~ of chironomids and gleaning frequency by individual Wigeon. Gleaning was observed exclusively on emergent vegetation in the morning and evening. During midday, gleaning occurred most frequently on water surface probably due to the diel emergence and swarming patterns ofchironomids. Gleaning was most frequently used by females, which is mainly due to their higher energetic requirements during the breeding seasons. I conclude that the increasing abundance of emerging chironomids in the spring is one important factor affecting time of nesting by Wigeon. Dept. of Animal Ecology, Museum of Zoology, University of Bergen, N 5007 Bergen, Norway. INTRODUCTION several weeks and months before migration to the Arctic (Raveling 1979, Ankney 1984). Most dab Patterns in avian reproduction ultimately are adapt bling ducks, however, obtain their requirements ed to and proximately generated by variations in (lipids, proteins, minerals) for breeding by storing food supply (Lack 1966, Daan et al. 1988). In order reserves and by utilizing resources on their breed to understand avian breeding strategies, it is impor ing grounds (Drobney 1980, Krapu 1981). Although tant to know how resources are distributed in space recent studies have shown that food quality in the and time and how the birds obtain them during their non-breeding season may influence timing and re breeding cycle (Alisauskas & Ankney 1985). -

Mitteilungen Aus Der Chironomidenkunde Newsletter of Chironomid Research

MITTEILUNGEN AUS DER CHIRONOMIDENKUNDE NEWSLETTER OF CHIRONOMID RESEARCH CHIRONOMUS Vol. 2 No.3 Miinchen, Marz 1982 CHIP-ONOMID RESEARCH 11 THE NETHERLANDS Bernard P.M. Krebs Chironomid research in the Netherlands goes back to Van der Wulp, who wrote various dipterological papers, amongst others several about chironomids. In 1898 he and De Mei,jere published a checklist of Dutch diptera's. Irl rece11L chir.onomid literature we can find his name as the author of different Orthocladiinae genera, e.g. Cri~otopus and Orthocladius and difrerenl species like Peiltapedilum sordens and Parachironomus -7 monochromus. In 1928 De MeiJere jnsist.ed in a paper on a revision of the Dutch Tendipedidae. Kruseman took up this gauntlet and in l933 he published his study about the "Tendipedirlae Neerlandicae". Quite different was the research of Van der Torren in the same period. He studied the midge-plagues caused by the closure and desalinisation of the Zuyderzee (now Lake Yssel). -n his unpublished report he de- scribed and discussed the symptoms, the abatement and the possibility of a second outbreak of this plague. At the end of the sixties new research was set up. The recent research can be dis- tinguished roughly in three classes: A) Applied systematical research for water quality and nature management, B) Fundamental research like chironomid ecology and taxonomy, C) Fundamental ecosystem research, of which the chironomid st,~dyis part of the whole research. A) Due to the large numbers of species (in the Ketherlands more than 400) and the possibilities to use the species for characterization of water quality and water economy, many research workers of (mostly) local governments, who are responsible for water q,~ality,are making a study of the distribution and ecclogy of chirono- mid larvae (and other groups of the macrofauna) In all parts of the country. -

Insecta: Diptera)

Hydrobiologia (2021) 848:2785–2796 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-021-04597-8 (0123456789().,-volV)( 0123456789().,-volV) PRIMARY RESEARCH PAPER Insect body size changes under future warming projections: a case study of Chironomidae (Insecta: Diptera) Rungtip Wonglersak . Phillip B. Fenberg . Peter G. Langdon . Stephen J. Brooks . Benjamin W. Price Received: 25 June 2020 / Revised: 4 April 2021 / Accepted: 16 April 2021 / Published online: 4 May 2021 Ó The Author(s) 2021 Abstract Chironomids are a useful group for inves- length with increasing temperature in both sexes of tigating body size responses to warming due to their Procladius crassinervis and Tanytarsus nemorosus,in high local abundance and sensitivity to environmental males of Polypedilum sordens, but no significant change. We collected specimens of six species of relationship in the other three species studied. The chironomids every 2 weeks over a 2-year period average body size of a species affects the magnitude of (2017–2018) from mesocosm experiments using five the temperature-size responses in both sexes, with ponds at ambient temperature and five ponds at 4°C larger species shrinking disproportionately more with higher than ambient temperature. We investigated (1) increasing temperature. There was a significant wing length responses to temperature within species decline in wing length with emergence date across and between sexes using a regression analysis, (2) most species studied (excluding Polypedilum nubecu- interspecific body size responses to test whether the losum and P. sordens), indicating that individuals body size of species influences sensitivity to warming, emerging later in the season tend to be smaller. and (3) the correlation between emergence date and wing length. -

Zootaxa, Diptera, Chironomidae

ZOOTAXA 752 Notes and recommendations on taxonomy and nomenclature of Chironomidae (Diptera) MARTIN SPIES & OLE A. SÆTHER Magnolia Press Auckland, New Zealand MARTIN SPIES & OLE A. SÆTHER Notes and recommendations on taxonomy and nomenclature of Chironomidae (Diptera) (Zootaxa 752) 90 pp.; 30 cm. 3 December 2004 ISBN 1-877354-76-7 (Paperback) ISBN 1-877354-77-5 (Online edition) FIRST PUBLISHED IN 2004 BY Magnolia Press P.O. Box 41383 Auckland 1030 New Zealand e-mail: [email protected] http://www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ © 2004 Magnolia Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, transmitted or disseminated, in any form, or by any means, without prior written permission from the publisher, to whom all requests to reproduce copyright material should be directed in writing. This authorization does not extend to any other kind of copying, by any means, in any form, and for any purpose other than private research use. ISSN 1175-5326 (Print edition) ISSN 1175-5334 (Online edition) Zootaxa 752: 1–90 (2004) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ ZOOTAXA 752 Copyright © 2004 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Notes and recommendations on taxonomy and nomenclature of Chironomidae (Diptera) MARTIN SPIES1 & OLE A. SÆTHER2 1 c/o Zoologische Staatssammlung München, Münchhausenstr. 21, D-81247 München, Germany; e-mail: [email protected] 2 Museum of Zoology, University of Bergen, Muséplass 3, N-5007 Bergen, Norway; e-mail: [email protected] Table of contents Abstract . 3 Introduction . 5 Methods and material . 5 General remarks . 7 Comments on individual taxa . -

Biodiversity of Family Chironomidae (Diptera) in Srebarna Lake (North-East Bulgaria) and Genome Instability of Some Species from Genus Chironomus Meigen, 1803

ECOLOGIA BALKANICA 2018, Vol. 10, Issue 2 December 2018 pp. 41-53 Biodiversity of Family Chironomidae (Diptera) in Srebarna Lake (North-East Bulgaria) and Genome Instability of Some Species from Genus Chironomus Meigen, 1803 Mila K. Ihtimanska*, Julia S. Ilkova, Paraskeva V. Michailova Institute of Biodiversity and Ecosystem Research, BAS, 2 Major Jiurii Gagarin Str., 1113 sofia, BULGARIA * Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract. The biodiversity of the family Chironomidae, Diptera in Lake Srebarna - a lake of natural origin, a Biosphere Reserve and a Ramsar Site of International Importance was studied. The conducted study revealed high concentrations of phosphates and some heavy metals (Cu, Pb, Zn, Mn, Fe) in the water. High concentrations of heavy metals (Cd, Cu, Pb, Mn) in the sediment were also found. Through the detailed analysis of the external morphology of the larvae and the species- specific cytogenetic markers of the polytene chromosomes of the larvae, we established a total of 16 genera and 11 species. Ten genera and eight species were new to the fauna of the lake. For the first time, we reported malformations in the larvae of some genera Endochironomus, Chironomus and Glyptotendipes (0.84÷2.04%) and species (Endochironomus tendens - 0. 29%). Genomic instability realized through somatic structural chromosomal aberrations in the polytene chromosomes of the four species of the genus Chironomus was found. Based on these aberrations, the Somatic index (S) was calculated (C. nuditasis, S-3.25; C. annularius, S-5.75; C. balatonicus, S-7.5 C. pallidivittatus, S-4.50). In addition, inherited chromosome aberrations have been observed, which were important for the adaptation of species to specific living conditions. -

Dezembro De 2008 FUNCHAL - MADEIRA

ISSN 0870 - 3876 BOLETIM DO MUSEU MUNICIPAL DO FUNCHAL (HISTÓRIA NATURAL) Suplemento N.º 13 16th INTERNATIONAL CHIRONOMID SYMPOSIUM SAMANTHA JANE HUGHES, MAHNAZ KADEM & MIGUEL ÂNGELO CARVALHO (Guest Editors) Dezembro de 2008 FUNCHAL - MADEIRA Editado pela Câmara Municipal do Funchal Composição: Museu Municipal do Funchal (História Natural) ,PSUHVVmRHDFDEDPHQWR2/LEHUDO(PSUHVDGH$UWHV*Ui¿FDV Foreword This special supplement of the Boletim do Museu Municipal do Funchal contains extended abstracts, based upon communications given at the 16th International Chironomid Symposium which took place at the Casa da Luz Museum in Funchal, 25th - 28th July 2006, and was hosted and organized by the Centre for Macaronesian Studies (CEM) of the University of Madeira (UMa). The symposium provided an opportunity for chironomid researchers to attend sessions where communications of a remarkable scienti¿c level were given in Palaeolimnology, Biomonitoring, Toxicology & Biomonitoring, Ecology, Taxonomy, Morphology & Systematics, Physiology & Physiological Responses and Biogeography & Biodiversity. CEM included some ³¿UVWV´ in the organization of this international cycle of symposia such as a session on Palaeolimnology, emphasizing the importance of chironimids in assessing both past and present impacts in global issues such as climate change, an open debate on “Divulging Chironomid research: bibliography and data bases´ and a post symposium taxonomic workshop held at CEM’s laboratory facilities where researchers discussed and examined material and shared ideas. We extend our sincere thanks to everyone who contributed to the symposium’s success and to the preparation and publication of these proceedings, in particular the Director of the Museu Municipal do Funchal for agreeing to the publication of the symposium proceedings as a special supplement of the Boletim and colleagues from CEM and the Instituto Superior de Agronomia in Lisbon who translated proceedings abstracts into Portuguese. -

The Impact of Shore Types on Benthic Macroinvertebrate Community Structure and Functioning in a Large Lowland River

The impact of shore types on benthic macroinvertebrate community structure and functioning in a large lowland river Dissertation Zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doctor rerum naturalium (Dr. rer. nat.) Vorgelegt der Fakultät Umweltwissenschaften der Technischen Universität Dresden von Dipl.–Biol. Marian Brabender (geboren am 05.09.1983 in Lindlar) Gutachter: 1. Prof. Dr. Markus Weitere 2. Prof. Dr. Dietrich Borchardt 3. Dr. Patrick Fink Eingereicht am: 28.11.2014 Verteidigt am: 23.03.2015 Erklärung des Promovenden Die Übereinstimmung dieses Exemplars mit dem Original der Dissertation zum Thema: “The impact of shore types on benthic macroinvertebrate community structure and func- tioning in a large lowland river” wird hiermit bestätigt. ……………………………………….. Ort, Datum ……………………………………….. Unterschrift (Vorname Name) Skizzen des ersten Planungsgespräches für das Dissertationskonzept. Beide Zeichnun- gen, die linke aus der Feder von Prof. Dr. Markus Weitere, die rechte aus meiner, ent- standen in der Stadtfelder Kneipe „Allards“. Trotz dieser künstlerischen Darstellungen wurde das letztendliche Design der Dissertation geringfügig abgewandelt. Table of contents Table of contents Table of contents ________________________________________________________________________________ 1 Zusammenfassung ______________________________________________________________________________ 4 Abstract __________________________________________________________________________________________ 5 General introduction and aim of the study ___________________________________________________ -

Karyotype Characteristics and Chromosomal Polymorphism Of

COMPARATIVE A peer-reviewed open-access journal CompCytogenKaryotype 12(3): 267–284characteristics (2018) and chromosomal polymorphism of Chironomus “annularius”... 267 doi: 10.3897/CompCytogen.v12i3.25832 RESEARCH ARTICLE Cytogenetics http://compcytogen.pensoft.net International Journal of Plant & Animal Cytogenetics, Karyosystematics, and Molecular Systematics Karyotype characteristics and chromosomal polymorphism of Chironomus “annularius” sensu Strenzke (1959) (Diptera, Chironomidae) from the Caucasus region Mukhamed Kh. Karmokov1 1 Tembotov Institute of Ecology of Mountain territories RAS, I. Armand str., 37a, Nalchik 360051, Russia Corresponding author: Mukhamed Kh. Karmokov ([email protected]) Academic editor: V. Golygina | Received 14 April 2018 | Accepted 27 June 2018 | Published 30 July 2018 http://zoobank.org/E0798FE0-109A-4EC2-A987-4895D7038A8A Citation: Karmokov MKh (2018) Karyotype characteristics and chromosomal polymorphism of Chironomus “annularius” sensu Strenzke (1959) (Diptera, Chironomidae) from the Caucasus region. Comparative Cytogenetics 12(3): 267–284. https://doi.org/10.3897/CompCytogen.v12i3.25832 Abstract The study presents data on the karyotype characteristics and features of chromosomal polymorphism of Chironomus “annularius” sensu Strenzke (1959) (Diptera, Chironomidae) from three populations of the Caucasus region (South and Central Caucasus, and Eastern Ciscaucasia). We found 17 banding sequences in the Caucasian populations. We observed inversion polymorphism in almost all chromosome arms except for arm G. The genetic distances between all the studied populations of Ch. “annularius” were cal- culated using Nei criteria (1972). In spite of relative geographic proximity, the genetic distances between populations of the Caucasus are quite large, and they do not form a single cluster of Caucasian popula- tions. The population of the South Caucasus goes to the European cluster, the population of the Central Caucasus goes to the Asian cluster and the population of Eastern Ciscaucasia does not belong to any of the outlined clusters.